Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this extensive and inspirational feature, Electronic Arts' Audran Guerard, an art director at EA Shanghai, explores what it truly takes to learn and grow as an artist -- and to create works that have meaning and interest for the players of your games.

July 19, 2012

Author: by Audran Guerard

In this extensive feature, originally started as a way to inspire those who work for him, Electronic Arts' Audran Guerard, an art director EA Shanghai, explores what it truly takes to learn and grow as an artist -- and to create works that have meaning and interest for the players of your games.

Cover art illustration by JiN.

I often receive emails, from art students, dreaming of a career in video games. (Poor souls, if they only knew.) They are looking for hints on their portfolio and seek guidance on how to land their first job. I can sum up most of these emails with one simple question: How can I improve?

I too, have pondered that question. I still am. The feeling of being stuck on a plateau is frustrating -- unbearable, I should say. In fact, that question came to the point of being an obsession with me. I combed everything I could to find answers: books, workshops, friends, and blogs. I was constantly on the lookout for crucial pieces of information to complete that puzzle.

How do you build your art skills? When asked, a lot of people out there will tell you, "by doing it," by being exposed again and again, by gaining experience. While this is generally true, I always thought that there was somehow something more to it. You could, after all, spend long hours honing your trade the wrong way -- and not improving much, if at all. This is what pushes me to write this today.

Keep in mind, building art skill is not easy. If you're looking for a shortcut, you'll be disappointed. I only know the steep uphill path that leads to better art, and that path has no final destination. The most terrifying aspect is that the more you discover about art, you realize how little you knew, and that there is so much more left to understand. So by all means do not consider this text as the ultimate "how to"; it's merely a series of hints and clues which, when you become aware of them, give you a new dimension of art to explore and untangle yourself.

Before we dive into deeper territory, I want to share some African words of wisdom:

Above all, we are artists! The fundamentals of good picture making should be your daily bread. We all know too well the technical tools of our craft. We depend on them. However, we should remember that they are just tools. We are the creative force behind the tools. Technology will only reflect what we input into it. Challenge it, cheat it; its only purpose is to execute your vision. As with a pencil and a white paper, it takes someone to hold that pencil to leave marks on the paper. The beauty of the lines is up to the might of the one who holds that pencil. Tech alone cannot make something pretty; it needs your input. In our trade, being good means how well you articulate your art fundamentals around the vision and execute the work technically through your medium, within an acceptable amount of time, in a collaborative work environment.

I will leave the technical implementation aspect to the side; it is not my concern with this article. I want to focus on the vision, the speed of execution, and the collaborative aspect of our job.

The most powerful tool I've come across that helped me to function with a visual design approach is the three concepts I'll discuss below. Together, they help me rationalize in my head the eerie concept and process of picture making, and help me communicate about art effectively across multidisciplinary teams. As an artist, these concepts help me to "get there," as opposed to "getting somewhere".

"Getting somewhere" is frustrating for the team because no one really knows where, how, and when the work is going to be finally completed. "Getting there" is motivating because the end result is clearly communicated, and it's easier to measure current status, receive feedback, and iterate.

You start with a vision, a clear intent, a desired goal, and with a rational approach through design principles, you guide every choice that will take you to where you want to land.

Here is a list of the most common Design Principles and Elements I use. There are multiple websites that explain, more or less, these principles and elements. I may in the future explain them in deeper detail.

The words above, when used as tools, concretely help you build your pictures with clear, precise direction. To me, they've been extremely useful as an art director to explain vision and provide feedback. They allowed me to see an image from a design perspective, thriving first for its abstract quality. When satisfied with the basic shapes, proportions, and their values, then I can focus on the actual storytelling as a whole in view of each individual element. There's no point in fine-tuning storytelling elements if your main underlying layer is not interesting to look at.

Most of the paintings that have survived the test of time and still hang in museums today carry a strong sense of design. Their primary appeal lies in the basic composition of shapes and colors, not in their depicted fiction. The fiction is a second layer that will only accentuate the first layer.

It should be your goal to build an image with clear intent, not to try and execute the vision instinctively. Don't get me wrong. There is nothing inappropriate with working with guts, fiair, and instinct; it will always be part of your internal response and feelings. But these words can help you rationalize these feelings and give you an efficient and simple way to include others for efficient collaboration. Why? Because it's hard for others to taste your guts, smell your fiair, and read your instinct. Besides, I'm not sure I want to stand this close to anyone... I'm a bit of an introvert.

You should also seek to deepen your awareness in these three categories:

1. Shapes / Silhouettes

We humans perceive objects by their edges first. So for clarity of statement, you should think silhouette first, and make sure your object is identifiable by it silhouette. Pretty much like the Terminator, when you enter a room, your brain scans and identifies your surroundings (the purpose is to highlight potential threats; we are so awesome).

To increase interest, things should be clear and easily readable, not confusing. Within your art style, try to make identifiable props and characters just by looking at the silhouette. We work in 3D, so it might be difficult to give a clear identifiable silhouette from every angle. But use the gameplay camera to identify the most important angle, and give it some extra love.

Often, a slight exaggeration will help you describe an object through its silhouette and enhance its emotional charge. Try to sprinkle a bit of caricature in your shape work, it will surely be... spicier!

Don't assume this doesn't apply to you because you work in a "realistic style". You still need some amount of characterization to make art interesting. You need to distort realism, to make it louder, in order to be entertaining.

Now be aware that your shapes/lines and their directions carry an emotional charge. You need to orchestrate these shapes and lines so they can carry a unified message. Horizontal shapes and vertical shapes do not evoke the same thing. One calls for quietness, and the other calls for austerity. Make sure your shapes' arrangement supports the ongoing story you are trying to tell.

Doberman photo by IIi Ivan; bloodhound photo by Claudia Krebs. Source: Wikipedia

Please bear with me for a moment while I wear the title of Captain Obvious. These two dogs trigger different responses; one looks much more aggressive than the other. It's all because of their physical appearances. The Doberman looks more agile, faster, and aggressive because of his lean and sharp silhouette. The bloodhound feels heavier and slower, and his droopy eyes give him an air of laziness; he doesn't look very alert.

These design attributes doesn't apply only to living things. You can create anything and give it a different appeal. You can design a cheerful looking table or a sad one. The story should dictate your design choices. Remember Anton Ego, from Pixar's Ratatouille? Let's revisit his office. His personality and physical attributes are reflected in his personal space. He, himself, is austere, tall, slender, and dark. His office has a high ceiling, a narrow space, tall vertical frames and windows, dim lighting and is hushed. Even if you're working in a so-called "realistic style", give yourself some freedom to customize things according to the story.

Colors & Values

"Colors" is a lengthy subject, and a very subjective one, too. There are no hard rules; if there are any, they all have exceptions. So just keep few things in mind: Colors come with their ranges of temperature and emotion, and based on the story you want to tell, there might be colors you want to avoid. Colors can also be used to help with readability of gameplay mechanics. Explosive red barrel! Ever seen that one?

Colors can be used to create symbolic links. This can be subtle but yet powerful, as in the intro sequence of Pixar's Up. The artists used the fuchsia color as an expression for Ellie, often seen on objects or clothing she uses -- and finally use that established symbol to illustrate her passing away when the pink sunlight disappears in the reflection of the window. Beautiful!

There are multiple books talking specifically about colors, but an efficient way to study colors is to watch movies and dissect the color choices made, and their purpose in the story. We're not only concerned with harmonious color combinations, but story mood and harmonious color combination.

Composition / Leading the Eye

Composition is probably the most elusive art concept. If I can reduce it to one simple statement, The art of composition is the art of directing the eye through a picture. Let just assume there is no bad compositions, only misused compositions -- stronger or lesser compositions. What may work in a specific story might not work in a different setup. Your sole goal with composition is how you want the player to read and understand the space/story that is being proposed.

The most common tool is to use conflict and contrast, and directional lines or shapes. Conflict in shape, conflict in color and value. The eye will usually jump on the highest contrast within a frame. When you have your point of focus, make sure the other elements don't fight too much for attention. At best, the hierarchical organization of your elements should altogether gradually lead to the focal point. Composition is often misunderstood, and reduced to the tier rule; there is much more to it.

Function, Function, and Function...

When trying to build a world, you want people to buy in, and forget they are within a fiction. You want to distract them away from the backstage. You don't want them to see the set; you want them to feel the world as naturally as possible. The props that will populate your world should feel believable and functional. It's a no-brainer. Your objects and scenes should be as descriptive as possible.

Too often I've seen artists struggling trying to embellish something by adding random details. They feel something is not quite right; they are trying hard to fix it, but unfortunately from an angle that isn't broken. With them, I will sit down and evaluate the piece from three specific angles.

Function in design. Does the object appear functional? Would I be able to use it if it was right next to me? How do I carry it, how do I turn it on, how do I access it? Can my hand fit on the handles? (Artists tend to make them either uber tiny, or friggin' huge.) What details can I add (or remove) to make it purpose or usability clearer?

Function in gameplay. In the desired experience, how important is that prop or space? What is its role in the whole level design scheme? How does the player interact with it? How can we help the player understand the desired interaction? Does it attract too much (or not enough) attention?

Function in story. Does this props or space sell the fiction well? Does it contradict anything? What story-related details can I add to add visual interest? Does it thematically blend well enough with its surroundings?

When you start adding details, remember that it's not because you can, but that it's because you should. We work under multiple types of constraints: textures, polygons, time. So you must select and prioritize what best characterizes your props, and work hierarchically from the most obvious "can't do without" to the lesser details.

Make sure what you add bring value to the game for the player, and make sure it doesn't conflict with your overall composition. It's best to evaluate all this from the player perspective, with as much of the other assets integrated as possible -- not the in Maya shaded view.

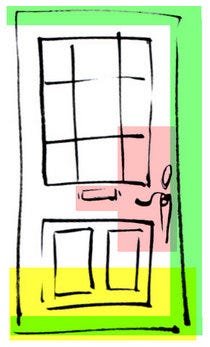

Here is a short example of details and story. While you were modeling and texturing the most beautiful door ever -- the second most popular prop after barrels -- your AD drops by and asks you to age it a bit. It feels too brand new. The reflex of many artist at that point is to jump into Photoshop, add an even layer of dirt on the entire diffuse and specular texture, and voila!

Here is a short example of details and story. While you were modeling and texturing the most beautiful door ever -- the second most popular prop after barrels -- your AD drops by and asks you to age it a bit. It feels too brand new. The reflex of many artist at that point is to jump into Photoshop, add an even layer of dirt on the entire diffuse and specular texture, and voila!

Well... let's push things further a bit. Let's work from logical "a cause and effect" point of view. By the way a door is used daily, there will be multiple distinct types of traces.

The pink area, is where the hands are more likely to touch the door, so over time, sweaty palms and greasy fingers will leave a thin layer of dirt. The yellow highlighted area is where the feet or objects (bicycle wheels and pedals, maybe) might collide with the door, leaving dents and scratches. It's an area also prone to water damage.

The green area will be stressed by the incessant opening/closing of the door, constantly hitting the frame, it will likely chip the paint off and wear the edge out more than the interior edges. When adding details, try to use them to tell believable micro-stories. The more believable they are, the more the player will buy in.

Drawing, sculpting, modeling, and texturing require an extra keen sense of observation. Seeing is the primary skill to develop in order to become a good draftsman. It's not about the pen or paper you use. It's not about Maya or Max; it's about your own ability to seize the truth about an object with top-notch precision.

When a 3D modeler is given a concept art, she needs to be sensitive enough to grasp the subtleties of the design and the character behind it. Often it's very difficult to turn a gestural speed painting into a 3D object. The key here is not to do a simple translation 2D to 3D. It's to re-create/re-interpret in 3D the gesture proposed in the 2D concept art. It's like listening to an interpretation of your favorite heavy metal band by a philharmonic orchestra. The two versions will sound very different, but both will vibrate the same energy if executed skillfully.

Artists look into evaluating shapes, volumes, their relations to each other, the pattern of the positive and negative space, their surface. We also look at the character of things, their age, wear, sturdiness or fragility, their stories. We need to select only the essential information. It's caricaturing on the go -- leaving out information that doesn't matter to focus on the truth. Become expert at oozing out the essence of things.

Seeing is not about being able to create a photorealistic drawing of an object. Art is not interested in duplication. Art in entertainment should be bigger than life. Art needs exaggeration in order to be convincing and entertaining. If your art direction calls for something dull, then you need to create duller than life. It work both ways; the nice becomes nicer, and the ugly gets... uglier.

From time to time in applicants' portfolios, I see highly realistic renderings of famous people done in pencil from photographs. If you're not at least as fast as a photocopy machine, it won't be impressive. I will always prefer a three-line drawing capturing the likeness of someone. I know that person has a keen sense of observation and is capable with very few lines of expressing ideas, feelings, or stories. Again, it doesn't matter which medium you use, whether it's an expensive 3D software package or a lost twig on the beach.

It comes down to observation. One way to practice your observation skill is to draw anything, anytime, all the time. Carry a sketchbook with you. Whenever you have five minutes to kill, commuting, at the bank, or sitting for a coffee, pull out your pencil and notepad, and draw something that is around you. It could be people; it could be an object. You sole focus is essence. You want to simplify some shapes, you want to exaggerate some others, and your personal style is defined by what you leave out versus what you keep in, crowned by what you add.

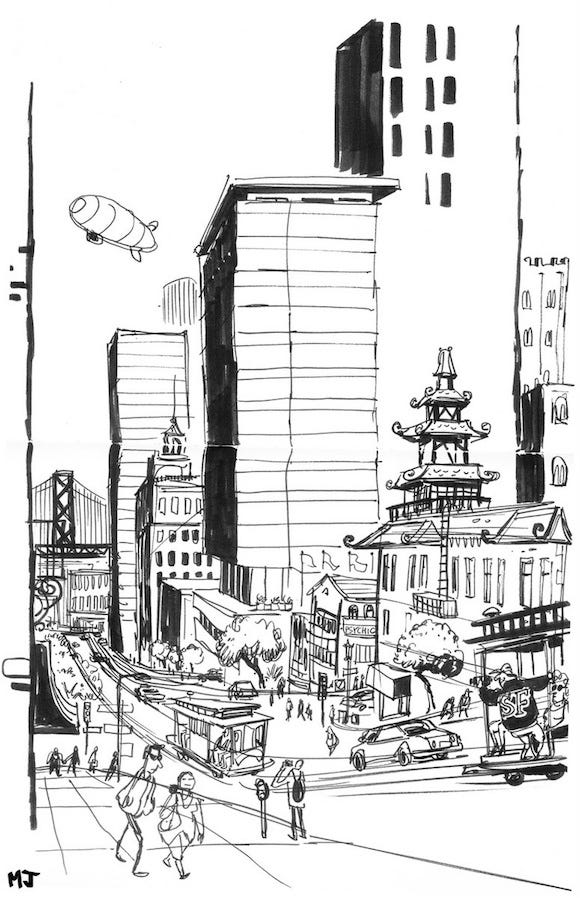

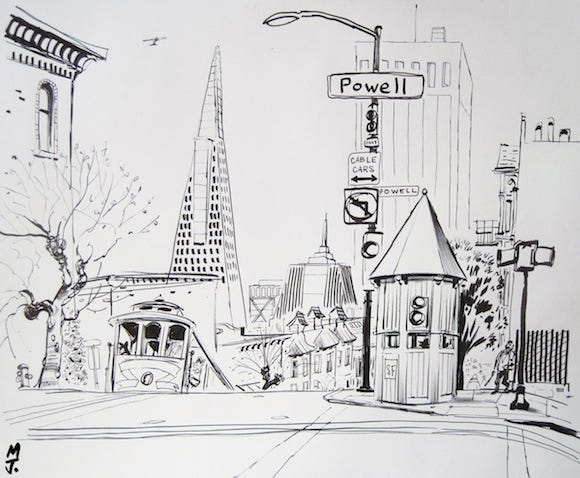

Here are two delightful drawings by Matt Jones. I really enjoy the way he depicts the city. The details he chose, ignored, enhanced, and weakened made his drawings more San Francisco than San Francisco itself.

Images graciously provided by Matt Jones, all rights reserved.

If you study life drawing, don't focus solely on anatomy; go for a story. Extrapolate, exaggerate, twist reality. This is how great drawings are achieved. Don't reduce yourself to the capacity of a camera. Be the artist you ought to be.

Images graciously provided by Matt Jones, all rights reserved.

There is a popular belief that goes, "I don't need to know how to draw, because I work in 3D." To that I would say, "Maybe. But why on Earth would you limit yourself?" The ability to draw is proof of your mental visualization and observation power. Many people think drawing happens between your finger and your pencil, but in fact drawing happens in your brain, using your ability to visualize something with extreme clarity.

If you have enough dexterity to hold a pen to write down your name, you possess enough dexterity to draw like most of the masters. The difference between you and them is the power of your observational skill. From my experience, the top performers in my teams were often good draftsmen. Not always, but they had the upper hand in speed of execution, quality of shapes, texturing, and concept art reading.

In the mid '90s, stricken by illness, Frank Frazetta couldn't rely on his right hand anymore. He started to train his left hand by drawing and painting. After few months, he was able to create some very decent pieces of art. Some critics even say that his drawing actually improved. Well, I don't know about that, but he drew skillfully with his non-dominant hand after a relatively short period of time.

My point here, again, is about the required dexterity to draw and paint. Because Frazetta already knew how to paint and draw in his head, it was only a matter of making his left hand as agile as his right. "Only" is an understatement; it still takes effort to get the brain to wire new neural connections. It must have required great patience of him, but he did it. At that point, his right hand had more than 50 years of experience in drawing and painting.

Another thing I could add about drawing is that it never gets easier with time or experience. It remains hard. It is not an automated task, like running or driving a car. Your drawings will become better over time. You'll gain confidence. The difficulty, however, will remain the same.

The goals you set for yourself will rise with your skills... all your life. Have you ever noticed how artists will often diminish their work in public? They'll only see "errors" they think they could have done better. Hence the saying "a piece of art is never quite completed."

Tricks and formulas are to be ignored; leave shortcuts to amateurs. When learning to draw, you want the real deal. It will be hard, but once the skill of draftsmanship envelops you like a second skin, you'll be free to express whatever you want to say. Tricks and formulas can't give you such freedom. They will work only for a tiny speck of possibilities.

For great artistry, you want freedom to make statements. The freedom to draw, sculpt or paint the views you have in mind. Your main concern should not be how to draw, but what to draw. Stop drawing three-fourths angle portraits because it's the only way you can draw a nose properly. Free yourself from that angle by learning to represent a nose in multiple angles. Stop drawing clenched fists; draw the full hands and let them participate in the story you are depicting. Stop hiding the character's feet in tall grass. Learn to draw feet, shoes, and boots in all possible angles. Try not to avoid what you consider your weaknesses; confront them.

Don't be afraid to use reference when possible. It's a clever way of working, assuming that you're not bluntly copying. A reference should give you some basic information about an object, an environment, a mood, or a character. You need to twist that information using your art fundamentals and the vision you're trying to achieve. You need to mold that reference to match your personal statement.

Don't think it all needs to come from your head. You have to have documents; don't assume good draftsmen draw everything from memory. They don't. Many use references. Hugo Pratt spent countless hours in libraries for his research for Corto Maltese. Norman Rockwell used models and photographic references for his masterpieces. Why is it perceived as a weakness to use references? How realistic is the expectation that one should know everything and draw from his head?

Explore multiple art styles from different cultures. Study old masters, new artists, and everything in between. Do not lock yourself in a specific aspect of art. It will limit your range of experiments and, thus, potential. If you're not fiexible and able to work in multiple styles, you're not preparing yourself adequately. The game industry is still in infancy. Many of the current products out there conform to a "realistic" art style. With the growth of casual gaming and multiplication of platforms available to consumers, developers will have to diversify their approaches from each other and strive for more originality in order to be noticed. I acclaim titles like Journey, Team Fortress 2, Castle Crashers, and Limbo for their mind-blowing visuals. Finally, something fresh to look at.

Realism is a touchy subject in video games. Many people believe that customers demand realistic graphics. I think gamers want authenticity; they want to be immersed and moved by the fiction that is being presented. Realism is actually easy to achieve, easy to communicate, and understood by all. This is probably why it is the first choice for developers. The tools are built for it; production is likely to be more predictable. It's less challenging in many ways.

In The Art Spirit, Robert Henri said, "When the artist is alive in any person, whatever his kind of work may be, he becomes an inventive, searching, daring, self-expressive creature. He becomes interesting to other people. He disturbs, upsets, enlightens, and opens ways for better understanding. Where those who are not artists are trying to close the book, he opens it and shows there are still more pages possible."

If your work is based on marketing studies of what the public seeks, you are keeping this book closed. They can't tell you what they want; we artists have to find new ways. It's part of our challenge. Stylization has a big advantage. The more you lean toward a specific style/abstraction, the higher the art challenge gets, but the better you can tell your stories and enhance the gameplay experience.

There is a tendency to dissociate gameplay and art. Too often the story is shoved down/rushed/overlooked, and is used as a tool just to create pretext for gameplay sequences. You may also hear from people that you can apply any art style over any gameplay. It's an incredible loss; a game is not solely about the gameplay. It's about a whole experience.

Art, story, and game design should come up together, amplifying each other and carrying a unified statement. The depth of the game experience depends on it. Can you imagine Shadow of the Colossus in a different art style? It's surely possible, but the three components (art, story, design) are so nicely welded together that it makes it hard to disassociate them.

Another reason why it's good to study multiple styles is to feed on them and enrich your personal style. There are endless ways of shaping or shading things. You can take influence from various sources; mixing them will result in something original in your own work. Art has a long, rich history, and it would be a mistake to ignore the solutions our predecessors have found. Why reinvent the whole wheel when you can take off where others have left? My painting skills quickly ramped up when I started scrutinizing Walt Disney movies. It helped me to understand how design was affecting my work and allowed me more freedom when painting outdoor scenes.

When you cultivate beauty -- when you seek it -- it will soon echo back in your life through other channels and media. Many famous painters didn't solely study painting; many of them used to sculpt, play music, branh into culinary art, poetry, or became unquenchable travelers. Be curious, explore, and experiment. Inspiration comes from everywhere, in many forms. The sum of your experiences will enrich the view and statements you have on life, the world, the whole universe and everything beyond. It will give you breadth -- a heavenly, sexy attribute.

Throughout the years, my biggest enemy has been myself and my expectations. You can't possibly work freely if you are constantly watching over your own shoulder -- the same way I can't work if someone stands behind me, watching every step. You need to create room around you -- room for errors, and room for experimentation, free of critics.

Often you'll find yourself disappointed with your output, the result being not quite what you had in mind. It's perfectly normal; I see it as a motor for personal growth. As you gain skill, you get pickier and pickier. There will always be a gap between your current output versus the thing you envision. This is where many people give up on art, unsatisfied and now convinced that it is not for them.

A piece of artwork is quite never finished; you will always find things to add or "fix". This is where collaboration can give you an incredible boost. Rely on your peers' eyes, and help them help you to clearly see what you are trying to achieve. You can choose to work in the dark, and never show your work, or you can stand out in the crowd and learn from how other people respond to your work.

We don't make art for ourselves. Art is communication, but for communication to happen, you need a receiving end. That receiving end is a great teacher. Your reaction to criticism and feedback, your attitude toward other artists who may hold a piece of advice you critically need, and what you accept will define you as a much as what you reject. Just like that split second of silence in a piece of music, it can enhance a whole composition... or not.

I want to warn the prospective students about the myriad of 3D schools out there. School is time consuming and really expensive. They run like businesses; that is what they are. The students are customers, and each one of them brings in a hefty sum. It's in the schools' interest to recruit as many students as possible.

They're not necessarily concerned with your professional success once you step out. They will teach you the technical side of 3D, the software package, the semantics, the process and workflow, team collaboration. But a big majority of them won't teach you art. The reason being that teaching tech is easy; teaching art is another thing.

Some more conscious schools will require a portfolio prior to your enrollment. These schools want to make sure you possess enough art background to succeed later, once you learn the technical side of things. Some other school will teach you both art and tech, usually with a longer curriculum. I favor these, if you don't have an art background.

About hiring, I've recruited a good number of artists, and there is one rule that never failed me so far. It's not about your experience; it's not about your education. What will get you a job is a mix of your personality and the promise of your portfolio. We like people who can work in a team, collaboratively. That's nothing new. We also like people who know more about art than the average person. We don't want peons. We want artists with opinions, vision, and the confidence to speak up. If a candidate shows great interpersonal skill and possesses a strong artistic value, I wouldn't mind hiring him even if his technical skills are not up there. For I know teaching tech is easy, but teaching art is another thing.

I will probably sound cliché once more, but I firmly believe that artists are made, not born. I don't believe in the innate gift of artistry. Many artists will tell you -- calling something you've sweated so much for a "gift" is demeaning. What we call "talent" is the inevitable byproduct of passion and hard work perceived in an individual.

Ultimately, what will make a difference in the long run is your own eagerness to grow. Don't ever settle for what you believe is your maximum. Many people will disagree with me on this topic, based on their personal experience at drawing. They probably failed a few times and now they are forcefully convinced that they are unable to hold a pen and draw, sabotaging every effort with the belief that they didn't get the magical dust of talent at birth. As the saying goes, every great draftsman had at least 10,000 bad drawings in them. Each of these bad drawings will grant you a piece of knowledge. Passion and hard work will get you where you want to be -- not magical dust.

The social success of an artist doesn't rely only on his draftsmanship abilities -- in many cases, not at all. There are hundreds, if not thousands or parameters -- probably the two most important being the social climate of your epoch and the message you are delivering. So no, you can't be DaVinci, but you are yourself, and you possess the absolute freedom to improve that self -- in a way that your peers, clients and the old masters could look at your work and see value in it.

Going back to those African words of wisdom, it's never too late to work on something that can feed you in the long run. All failed artists have one thing in common: They all have quit too early. So just hang on, don't ever give up, keep learning, keep pushing, keep growing. The ensuing will be a byproduct of your determination.

I would recommend these blogs to anyone willing to crank up their game. These people unknowingly helped me on that journey. They left valuable clues behind them in their ascent.

http://sevencamels.blogspot.com/

http://gurneyjourney.blogspot.com/

http://artandinfluence.blogspot.com/

http://nathanfowkes-sketch.blogspot.com/

https://one1more2time3.wordpress.com/

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like