Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This is a hopefully human readable version of my second paper published in the Computer Games Journal. It's about the stats that have emerged from the Meeple Centred Design project with regards to game accessibility.

This is a modified version of a post first published on Meeple Like Us.

You can read more of my writing over at the Meeple Like Us blog, or the Textual Intercourse blog over at Epitaph Online. You can some information about my research interests over at my personal homepage.

---

This post made possible thanks to the generosity of our Patreon backers!

Heron, M. J., Belford, P., Reid, H., Crabb, M. (2018). Eighteen Months of Meeple Like Us. An Exploration into the State of Board Game Accessibility. The Computer Games Journal, 7(2), 1-21. [Available online from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40869-018-0056-9]

Like what we have here but not sure how to go about it yourself? Well, consultancy services are available.

As many of you know, I’m a university lecturer. One of the things that I have to do as part of that is publish papers in academic journals. It’s been hard to find an appropriate publication outlet for work on board-game accessibility – it doesn’t fit anywhere especially neatly. Well, for a fair few months I’ve also been acting as guest editor for a special issue of the Computer Games Journal. That special issue was on game accessibility and we broadened the scope of the journal to include games of any stripe. Two papers on the topic of our board game accessibility work were submitted and accepted. I wasn’t able to approve or peer review either of those papers (obviously) so they have gone through the usual quality control processes you’d normally expect of a Springer journal without my sticky fingers probing into their various nooks and crannies. Rather than simply link the papers to you and forget about it I thought I would actually engage with my responsibility to communicate specialist academic literature to an audience made up of real people. I think that’s important because, by and large, academic writing is obtuse and impenetrable to outsiders. I try to do my best to be entertaining within the confines of the format but you know – success is mixed and whimsey is often the first casualty of Reviewer #2.

These papers though contain an awful lot of information that you might find useful, and I’m going to summarise the findings and processes so you can decide for yourself if you want to actually read the full things. As we go along I’ll also try to explain what the different parts of an academic paper are doing – every section has a job to perform. It might look like academics are just tedious blowhards in love with their own text. That’s true. The format of a journal paper is also designed to ensure it covers all the bases that people expect.

These papers are published Open Access which means they aren’t hidden behind a paywall. Anyone can read them, and that’s hugely important to me as an advocate for a cause. People not being able to get hold of these papers would have been an ironic inaccessibility all of its own.

This is the second post on papers we’ve written from the work we’ve been doing over the past two years. You can find the first post here and it talks about the toolkit we use to do teardowns. This post is about results and observations. The weird timescale of academic publishing here means that despite the paper being published last month it’s already seven months out of date. Also, due to the nature of the data gathering process the figures in this paper do not reflect that which has been published on the site – we have a backlog of around 24 teardowns that haven’t been published and the order in which they end up on the site is driven by all kinds of weird and frivolous external factors. If you want to see some real-time stats derived from work that’s been published we have those available.

As is usually the case for a paper like this, we begin with a literature review that sets the academic context of the work. For this topic, there’s precious little. Video game accessibility is a much bigger, better explored topic because it fits more neatly into the usual academic publishing niches – it’s a reasonable fusion of Ludology and Human Computer Interaction. Board games get a fair bit of academic attention, but usually as a pathway to something else. For example, board-games as tools for supporting play therapy, or game rulesets as formal systems by which you might train artificial intelligence agents. Work on board game accessibility is all but non-existent.

And that’s a shame, because it’s an incredibly rich area. Accessibility for physical games is a far more complex topic than digital games because real world logistics introduce new and complex considerations. There is no per-unit implication that comes along with making a video game more accessible. That’s not true for a board-game. Slightly larger tokens might be the difference between a game selling at $40 and $45 once you take into account additional size of boxes, weight, cost of materials, shipping of containers, and so on. The complexities of the costing of accessibility in board-games is a thing we haven’t even touched on with the site although, you know, give it time.

That’s before you even get into the issue of what it means to play a board game. With a video game you have a display, some device to process input, and the input peripherals themselves. We know what it means when we talk about the interface to a video game. What does the equivalent interface look like for a board game?

I’ll tell you – it looks like nothing because there isn’t one. The range of interaction expectations in tabletop gaming are phenomenally varied, and the skills required to play are equally so. We can’t talk about more accessible tabletop game interfaces because there is no consistency in terms of what that means. We need to go deeper, which is why we do so many teardowns on so many games. The problem domain here is incredibly broad and while we’ve explored a lot of games we still haven’t even scratched the surface.

Mainly what our work has shown is that board-gaming genuinely can be a hobby that works for everyone provided they are willing to be flexible on the range of games they want to play. Our work has also shown that board gaming as a hobby could easily be more accessible than it currently is.

There are problems with these condlusions which we’ll get to, and also problems with how we feed these observations forward. Our teardowns are relatively specialized documents, useful (we hope) for people looking to see if a game is suitable for them. They are less useful for those looking to extract generalisable guidance for how to make their own games more accessible. There’s a project in the background aimed at addressing that, but in the meantime the site serves as a repository of case studies without any clearly communicable lessons in easy-digestible chunks.

An issue here is that while guidelines are important, they’re not actually very good in complex domains where nuance and intersection are complicating factors. Context is everything here, and context is lost when you attempt to generalise. That’s a problem that remains to be solved. Our todo list is much longer than our ‘have done’ list.

It’s impossible for us to address even an appreciable fraction of games released on a yearly basis. BGG’s stats suggest that in 2016 over 5000 new titles were added to the database – these include print and plays, expansions, new editions of old games and so on. The number of these that translate directly into brand new games is up for debate. Whatever that number is though, even if only 1% of those were new games (and it’s a lot more than that) we could barely keep up. Board games hold their value and relevance – video games are largely forgotten after twenty years except for within niche and hobbyist communities. For a board game, that might just be the point it starts to get its moment in the sun as it is discovered anew.

As such, we have a more pragmatic approach than simply ‘tell people what games are accessible’. We can’t do that. Our focus is on the BGG Top 500 – not exclusively, but the largest proportion of our efforts get invested in the games that appear on that list. Our goal is to cover around 10% of that list every year, although in the past two years we’ve only managed a touch over 9%. At the time of writing this post we’ve managed to write (but not necessarily publish) teardowns for 18.8% of the list. Currently on the site, our real-time tracking shows the following coverage:

Coverage | Percentage |

|---|---|

Top Ten | 30.00% |

Top One Hundred | 18.00% |

Top Two Hundred and Fifty | 18.80% |

Top Five Hundred | 16.20% |

Top Thousand | 10.10% |

The BGG Top 500 is not actually a good list – it lacks curation, internal consistency, or any agreed upon meaning. However, it is a list and otherwise the site focus is simply ‘whatever we play whenever we play it’. And truthfully that’s a not-insignificant part of our selection process – we cover things as we play them. It’s just that we try to play things likely to lean into the site objectives. We don’t sacrifice our joy of gaming in service of the site, although we do on occasion gesture threateningly towards it with a ceremonial knife. Each game needs to be played often enough that we are sure we have a good feel for its accessibility (and for how good it is as a game). That means that every so often we have to push ourselves to play a game we’d really rather see the back of. A few of our snippier reviews might well be interpreted in that light – the perspectives of people that played a game beyond the point they had decided they weren’t having any fun.

A fixed project scope is obviously vital in making actual progress towards a goal. Otherwise the site would be constantly pulled in lots of contradictory directions by whim and circumstance. While progress towards meaningful coverage of the BGG Top 500 is slow – and made more complicated by the fact the composition of that list shifts on a daily basis – it does at least give us something for which to aim. Importantly for an academic paper being upfront about the scope ensures that people don’t criticise the results for being something other than what they were originally set out to be. For example, we don’t discuss Monopoly or Scrabble on the site and if you take a more mainstream view of board-gaming the first question a reasonable reader might have is ‘Why on earth not?’. The scope section of a paper tries to preempt questions of that nature.

I made some mention in our previous Patreon supported post that this work comes with a lot of caveats and limitations. I can’t emphasise enough how true that is – these are not objective rankings even if they are done with reference to a formalised set of heuristic lenses. For one thing, the toolkit we use requires adaption and reconfiguration in specific contexts – that’s the nuance that makes it difficult to provide useful generalised guidelines. There are games that make use of scratch and sniff mechanisms, other games that rely on players to supply their own components. Some change through play or adapt to choices made. That means that the task of doing a teardown isn’t simply working our way down a checklist. It’s an act of some analytical subtlety. That’s why we play each game a minimum of three times (in 95% of cases) to arrive at our accessibility recommendations. The recommendations are informed but that’s not the same thing as the recommendations being correct.

We use letter grades that convert into number grades for our analyses, and these focus on several categories of accessibility:

Lens | Description |

|---|---|

Colour blindness | Relating to issues where colour is used as the sole channel of information for game state, and how the palette chosen works for that |

Visual accessibility | Relating to issues of visual impairment, primarily where there is some degree of ability to differentiate visual information. Total blindness is considered in these sections, but it is not the primary focus. Later work for the project is planned to address this |

Physical accessibility | Relating to issues of fine-grained or gross motor control. Issues here include elements of dexterity, precision, and the extent to which a game facilitates play with verbal instruction |

Cognitive accessibility | Relating to issues of fluid intelligence and crystalised intelligence (Cattell 1963). Game complexity is an issue here, but it is not necessarily a predictor of the accessibility of the game in the end. Even very simple games may be cognitively inaccessible. Also included in this category are issues of expected literacy as well as implicit and explicit numeracy |

Emotional accessibility | Related to issues of anger and despair, and how they might manifest through score disparities, bullying through game mechanisms, and the extent to which the game requires players to deal with stress or upset |

Communication accessibility | Related to issues of articulation and perception of communication. Literacy is discussed here too as are the patterns of communication. In this section we work on the assumption that a group of players has some means by which they can communicate in day to day life, so we address only those elements specific to the game itself |

Socioeconomic accessibility | Related to issues of representation, diversity, and inclusion. Heron (2016) outlines these as issues of an accessibility of perception. Also covered in this section are costs and business models including when games have collectible elements or whether they work on the assumption of expansion |

Intersectional accessibility | Related to the accessibility issues that might arise particularly through the intersection of other categories above |

Each game received a full discussion of issues relevant to each category, and a recommendation is given in standard alphabetical grading. Those grades correspond to the following rough evaluations:

Grade | Numerical value | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

A | 14 | Strongly recommended—suitable for anyone with accessibility concerns in this category |

B | 11 | Recommended—likely suitable for anyone with accessibility concerns in this category, but there may be some small issues that need resolved |

C | 8 | Tentatively recommended—can likely be made playable although there are substantive concerns in particular cases |

D | 5 | Not recommended—can possibly be made playable but only with extensive modifications or impact on game enjoyment |

E | 3 | Strongly not recommended—it is unlikely this game will be enjoyable by anyone impacted by issues in this category |

F | 0 | Stay away—it is believed this game is fundamentally incompatible with issues that emerge in this category |

The numerical conversions are used to handle averages, standard deviations and other such straightforward evaluative calculations. A plus or minus is permitted in every category (save for E and F) to allow a slight amount of discretion to indicate when a game leans one way or another. Those don’t change the broad flavour of a recommendation but they do change perhaps the strength of it.

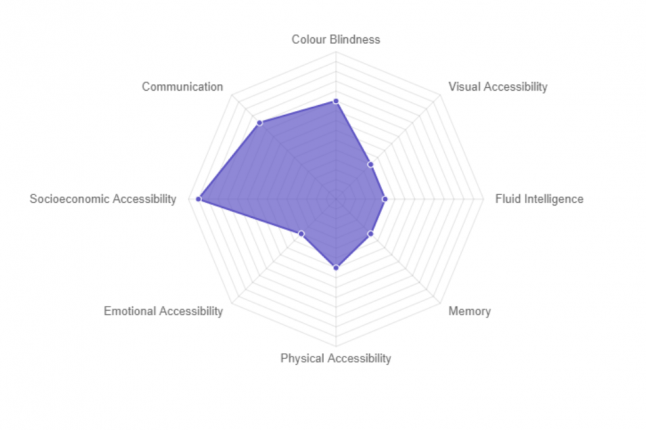

These numbers are also used to generate the radar charts that accompany each of our teardowns. Radar charts are an intensely problematic way of representing data, but so is every other kind of chart. What you gain in tractability of data you lose in its nuance (much like with guidelines).

However, the charts are provided with a consistent convention and as such they can be used for an ‘at a glance’ way for players to associate particular patterns of interaction with their own personal requirements. For example, our chart for Tiny Epic Galaxies:

If you see a chart that looks a bit like that you’ll have a reasonable idea of how likely it is to represent problems or opportunities for you as a player. As ever, the real meaningful unit of our accessibility analyses is the individual teardown category where we have time to be reflective.

If you see a chart that looks a bit like that you’ll have a reasonable idea of how likely it is to represent problems or opportunities for you as a player. As ever, the real meaningful unit of our accessibility analyses is the individual teardown category where we have time to be reflective.

That’s the methodology. Now for the limitations… these are hugely important.

So important in fact that every teardown we publish includes a disclaimer that these recommendations do not derive from embodied experience of disability. They are ‘theorycrafted’ because logistically there’s nothing else we can do. We don’t have hundreds of thousands of pounds to pay an army of volunteers to play and assess games for the project. Volunteers that will consistently lend their labour for nothing are rare and unreliable. Even if that were not true we can’t expect those excluded by game mechanisms to be able to articulate how they work when their very inaccessibility prevents players developing the necessary experience.

The model we use for evaluation has then a fundamental weakness – they are written from a primarily abled perspective. That perspective is mostly from someone who has been working in the field of accessibility for many years but it’s still the case that lived experience trumps academic experience in every way. At best what we can do is openly solicit critique from the community and fold that in when it’s appropriate. We have adjusted grades in many categories for many games in light of reader feedback, and we provide change logs to show when that has happened. At no point does a teardown indicate a definitive conclusion – all results are subject to change.

For the socioeconomic sections too there is a representative bias in that the largest majority of these posts are written from the perspective of a cisgendered male of a relatively privileged background. That skews the coverage somewhat as you might imagine. Other viewpoints on inclusion and representation are incorporated where provided and appropriate.

That’s really what we have then – each recommendation grade is a subjective data point written from the perspective of an informed but not embodied writer. They are subjective, qualitative judgements on how the interaction patterns of games manifest. Even if that wasn’t the case, the letter grades would remain problematic. It’s impossible to collapse the sophistication of complex accessibility requirements into a single letter grade in a handful of accessibility categories. A game that requires gross motor control might be perfectly playable for someone with nerve tremors and vice versa. All our recommendation grades do in the end is put a marker in some territory and say ‘Hey, look at the write up if this matters to you’.

To quote directly from the paper we’re discussing here:

They represent points of interest that have been mapped in the accessibility landscape. However, they also suffer many of the same issues that plagued early real world cartographical efforts. Occasionally a hazard that sinks a boat is missed, or an explorer marks ‘here be dragons’ to indicate danger where none is to be found.

The limitations of the site are important – that’s why I bang on about them so often. As I’ve said before – nobody is more critical of this work than me. Reddit included.

So, on to the GOOD STUFF – the results. You’re probably aware that we have a full master-list available – that’s the engine that drives our plugin shortcodes and the stats calculations on the sites. When we wrote this paper, N=116 (which means we had 116 games that we looked at. Only a portion of the analyses had actually made it to the site). However, that was seven months ago and now we have that many games on the site and still 24 or so in the buffer. As such, while it looks like we’ve now published all the games that we said we’d analysed in the paper it’s not quite that simple. In a small number of cases too accessibility grades have changed in the meantime as a result of new data points or perspectives.

As such, the site data is never going to be a perfect snapshot of what is in the paper. That represents the analysis as it stood at the point of it being submitted to the Computer Games Journal, which in turn was an analysis as it was at the point we finished writing it. Still, the most interesting thing we will perhaps get out of a post like this is a view of how the figures evolve as new games get added to our database. Expect to see in the future a snapshot provided on a year by year basis, if I remember to do it and if the site’s Patreon is sustainable enough to support that kind of work.

Colour blindness, despite being one of the simplest issues of accessibility to address in most circumstances, remains a persistent and ongoing problem. It’s rarely so bad that it stops people actually playing if they are willing to make some compensations. It’s far more common that it has a notably deleterious effect on game experience. The biggest issues here tend to be in piece discrimination – telling the pieces of one player apart from another because of colour palette clashes. Relatively few games make colour identification or pattern matching a more substantial aspect of the experience but those that do are correspondingly more problematic.

Colour Blindness, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a B grade. Numerically this comes out as a 10.92 average with a standard deviation of 3.30.

By and large colour blindness is a persistent consideration rather than a regular and critical barrier to play. As you can see though – there are circumstances where it is and in almost every case they could be easily avoided with the adoption of simple patterns, textures or iconographic design.

One of the critical mistakes we made early on with Meeple Like Us was to treat Visual Accessibility as a single spectrum with ‘fully sighted’ on one end and ‘totally blind’ on the other. While that makes a certain amount of sense it does mean that the recommendations we provide don’t take into account the logarithmic curve of actual accessibility. The impact on game experience at one end of the scale is not linearly related to that at the other. That’s a problem with our data and one that I will address when it’s possible to do so. As such, these grades skew somewhat upwards because those with total blindness have much more intense considerations that are not fully reflected in the grade.

Visual accessibility, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a C- grade. Numerically this comes out as a 7.05 average with a standard deviation of 3.41.

However, even within this we can see that these results tend very much towards inaccessibility. Many games require a large amount of ‘table knowledge’ from players – it’s important that people can work out what’s going on and what relates to them. Some games though simply have presentation blunders that result in poor contrast, busy graphical layouts or a lack of consistency in design. Some games use hidden hands of cards with complex effects or require players to obscure game state from other players. This is an intensely problematic hobby for people with visual accessibility needs.

Most of the games in this hobbyist space have complex rules, or complex game systems, and these rarely mesh well with impairments that impact on crystalised or fluid intelligence. As with our grades for visual accessibility the ratings for this category skews upwards beyond what individual games would tend to suggest. We consider cognitively accessible variants as part of this section – house rules are an incredibly powerful tool for accessibility. Much cognitive complexity can be reduced by limiting the importance of scores or looking at co-operative rather than competitive variants. As such, while a game may be deeply inaccessible it may still be playable as a house-ruled variant. Our grades reflect that.

Fluid intelligence, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a C- grade. Numerically this comes out as a 7.40 mean with a standard deviation of 3.84.

Unsurprisingly the games that receive the most attention on BGG and other enthusiast forums are those that are more tactically intricate or strategically complex. They tend to stress deep and synergistic thinking. However, it’s not a simple correlation that game complexity relates to cognitive inaccessibility. Some of the games that have the lowest weight in BGG are also the ones that ask the most of players in terms of this category. There is a wide range of grades here then, from those games that are likely playable by everyone to those that are likely only playable with considerable ongoing cognitive costs.

Most games do a reasonable job of making sure players don’t need to specifically remember elements of game state – explicit tracking often goes down into the level of having special tokens to remind people who the first player was. However, many games do benefit heavily from players being able to telescope their thinking forward or backwards – to understand how what they did in the past will influence what happens in the present, and how that in turn influencs the future. Complex state-dependent rules and conditional game systems also add a burden of memory – remembering to do a thing under certain circumstances is costly in and of itself without adding in the additional difficulties of remembering what has to be done. Remembering rules can be difficult, and rules-heavy games in particular often do quite poorly in this category.

More than this though many of the games we look at on Meeple Like Us require players to hold a long term strategy in mind and behave tactically in accordance with that plan. That requires sophisticated mental modelling of game state, game rules, and often the game state of other players where it intersects with our own. The spread of our recommendations in this category is shown below:

Memory based accessibility, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a C+ grade. Numerically this comes out as a 8.73 mean with a standard deviation of 3.86.

Here, collegiate support from the table can have a powerfully positive impact on the accessibility of the games people play. We work on the assumption with MLU that people are as interested in the communal fun as they are in their own, and that means we tend to expect people will point out when memory lapses are disadvantaging a player. That’s not a reasonable assumption for some games, but we tend to discuss that in the teardown where it is appropriate.

There is a relatively strong profile of results in this category, but again that skews upwards because we consider the feasibility of verbalisation. Verbalisation permits a player who cannot interact with game state to still issue meaningful instructions for another player to enact on their behalf. In conjunction with a card holder or other accessibility aid this permits a wide variety of games to be played and fully enjoyed since their fun is not to be found in their tactility. The profile of grades we have for the paper is shown below.

Physical accessibility, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a C+ grade. Numerically this comes out as a 9.24 mean with a standard deviation of 3.48.

However, it’s important here to remember that part of the fun of boardgames derives at least in part from the tactility of the experience and some games emphasize this more than others. Some games work on the basis of physical dexterity or have a real-time or simultaneous aspect that makes it difficult for players to act on behalf of another. There is a low-grade, persistent enjoyment that comes from simply engaging with nice game components – it’s not insignificant in any game but our recommendations here are bound up in whether or not we believe the tactility is a major part of the experience.

All of the results in this section must be viewed, to a degree, through a social lens. Even the best performing game in this category can be a problem if a group contains a bad winner or a poor loser. Any game can be a trigger for upset and anxiety if played by people actively looking to undermine the fun for others. Some games though contain game systems that are more likely to bring these kind of problems to the fore. Some games permit or even incentivise ganging up on an emerging winner, or a vulnerable loser. Some games have a sheen of intellectualism that equates skill to intelligence. Generally modern game design does a reasonably good job of limiting these kinds of issues which results in a generally strong performance.

Emotional accessibility, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a C+ grade. Numerically this comes out as a 9.44 mean with a standard deviation of 3.33.

Many of the most problematic game systems have been reduced in impact with modern games. Player eliimnation is relatively rare, and collaborative games have become increasingly popular as a way to enforce collegiality and shared accomplishment. However, those in turn tend to be quite difficult, working as they do on a system of an escalating despair curve that presents a challenge intended to be difficult. Some games are almost masochistic in their expectations and they take a certain degree of emotional resilience that impacts heavily on grades in this category.

Board games share a number of features with video games, but most importantly in this category is in the similarity is to be found in the often cursory treatment of women and non-white characters. Often when they are included it’s in the most half-hearted or desultory fashion. Occasionally women are included but in the most regressive ways. It’s better in modern games than it it is for older games, but the figures below tell a distorted story.

Socioeconomic factors, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, average out at a B. Numerically this comes out as a 10.79 mean with a standard deviation of 3.06.

This category tends to address issues of economics as well as sociology because they are often bound up together. Many games bundle ‘additional representation’ into expansion packs and collectible promos as an example of how that might manifest. An affordable game that scales to many players will be lifted upwards because of its economic factors even if its representation would pull it down. Similarly, games with good representation may be pulled down by predatory business models. As with every category, individual teardowns are considerably more precise in this regard.

The grades skew high partially because of that but also because there are many games that contain little or no representational art at all. Many games are abstract and eschew theme in their art. Many are thematic but represent their aesthetics through evocative graphical design that doesn’t include people – space ships and dark forests and the like. Other games shore up the stats by doing an especially good job with representation, including a wide range of ethnicity and genders, even occasionally characters coded as non-binary. These raise the average recommendations while games drag the values down. There are many games that contain overly-sexualised art, demeaning portrayals of women and minorities, and content that is homophobic or transphobic. Many of these are outside the scope of the Meeple Like Us project, but they still exist. The averages in this category, from my own personal perspective, are not entirely representative of the individual nuances of the work we’ve been doing.

Games only rarely require communication – informal table-talk is the most important part of most social gameplay. Some games though do depend on ongoing and complex discussion of strategy, or negotiation, or interpretation of language under challenging constraints. Generally if someone is reasonably literate in the game’s language there are relatively few games that present a challenge in this category. It is easily the most accessible of the categories we look at here on Meeple Like Us.

Communicative factors, according to the rating and numerical weightings outlined above, averages out at a B+. Numerically this comes out as a 11.47 mean with a standard deviation of 2.89.

Generally games that do poorly in this category are explicitly expecting players be able to interpret and manipulative communication to achieve complex gameplay effects. They may involve lying or bluffing or misdirection. By and large this is a category where the prime unit of inaccessibility is to be found in individual titles rather than in the hobby as a whole.

This is our first formal report on the accessibility landscape of tabletop gaming, and it shows the areas where we believe games are most accessible as well as those where there are the largest challenges to overcome. However, as we noted above, these are not generalisable into actionable guidance for developers and designers. The Tabletop Accessibility Guidelines are the next major phase of this project. There is a working group for this that includes researchers, designers, publishers, manufacturers and gamers with disabilities of all kinds. A number of candidate guidelines have been put together and the next stage is condensing them down into a set that is small enough to be tractable but large enough to be comprehensive. This work is ongoing.

Essentially our focus is to provide a set of guidelines that are evaluated according to several key principles:

1. Is it useful to those with accessibility considerations?

2. Is it feasible for game designers to include accessibility support of this nature?

3. Is it possible for game publishers to support accessibility features of this nature?

4. Is it economical to manufacture accessibility support of this nature?

Guidelines will be offered in terms of their impact but also in terms of how many of these principles they honour. The intention is to offer a sliding scale of accessibility that goes from easy fixes anyone can do towards more aspirational goals.

Along with this, the work of Meeple Like Us continues as we add more data points to our map of the accessibility landscape. To help people with navigating this growing data set we have been adding tools like our recommenderto help people narrow down on those games most likely to work for them and the groups with which they play.

This work is problematic in many ways, and we’ve discussed its limitations above. Even if it wasn’t, we cannot possibly keep up with the publication shedule of new games and have not yet managed to cover an appreciable fraction of the games that have hit the BGG Top 500. As to the whole BGG catalogue, well… there are around 95,000 games stored in its databases . Every week this project falls farther behind. The recommendations are intensely subjective, lack an embodied perspectve, and reflect the inherent biases of the methodology.

That is not to say that the work has no merit – obviously, we believe the exact opposite. We must though be honest in where we feel the work falls short. Our choice is between ‘doing something imperfect’ and ‘never doing something perfect’. We chose the first of these. If nothing else, the work of Meeple Like Us is supported by a reasonably large and reliable audience and this is helping raise the profile of the issue. The work has already lead to numerous collaborations with publishers and designers, and we hope to continue to build and develop those relationships as time goes by.

In the end, part of the solution to the methodological problems with Meeple Like Us lies in the philosophy of the teardowns themselves. They represent the start of a conversation, not the end of one. If people have corrections, observations or adjustments to grades we are always willing to listen.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like