Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"I had to start making sounds behave unnaturally for very specific design reasons, but everything started like I was shooting a movie and placing things."

The Vale: Shadow of the Crown is a sweeping fantasy tale played in near-complete darkness, and for good reason. The auditory adventure tells the story of a blind princess who must traverse a dark and treacherous valley known only as 'The Vale' by attuning her remaining senses to the world around her.

It'd be easy to use words like 'novel' or 'gimmick' when talking about The Vale. It would also be unfair. Game director and Falling Squirrel boss Dave Evans spent five years working on the project to ensure it could deliver absolute immersion, blending binaural audio (inspired by the technology's emergence in the VR scene) with RPG and combat mechanics to create what he hoped would be a AAA experience in all but name.

Achieving that goal, however, wasn't always straightforward. Evans recalls how one of his first major design breakthroughs was the realisation that working on a smaller, more intimate scale would ultimately allow players to better connect with the world around them -- especially when it came to dispatching some of The Vale's more unsavoury characters.

"It's an ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) sort of thing. Where there are these feelings of things being close and in your ear and moving around your face. So obviously that influenced combat. There is ranged combat, because we wanted to mix it up, but combat at its best is really close and intimate, and about hearing breathing, footsteps, shuffles, and armour clinking. Things that you don't normally pick up on. So there's an intimacy that's different with combat," explains Evans.

"[Delivering that intimacy] is not hard to do as long as you find good sound packs and spend time figuring out which tells pop out of the soundscape, and what other things can be relegated to the background. There was a lot of sound balancing that came with that."

When it came to implementation, Evans avoided compressing the audio as much as possible. He wanted to ensure there was more width and breadth to the frequency, allowing players to quickly identify the sensory flourishes (heard in the gameplay video below) that pulled each combat encounter, character interaction, and environment into the material world.

Although prioritising depth of sound was essential, Evans spent a lot of time wrangling some of The Vale's more important cues -- such as beacon sounds that direct players to objectives -- into place. "One thing I wrestled with forever, and never really knew exactly why it worked, were the magic beacon sounds. I found those became competitive with other sounds as soon as you had two objectives, like 'find this magic object but avoid or fight these beasts,'" he says.

He points out that while some players might want to dart into battle, others may intend to avoid some encounters altogether and head in the direction of another objective. It was crucial, then, that players were able to effectively differentiate between those guiding sounds.

"I had complaints like 'that beacon sound is making it hard to hear what I care about.' So in order to add agency, I had to make both of those effects something you can tune your brain into, and eventually landed on a sound that allowed players to ignore it when they wanted to concentrate on something else, or totally zone in on it and follow it to their objective.

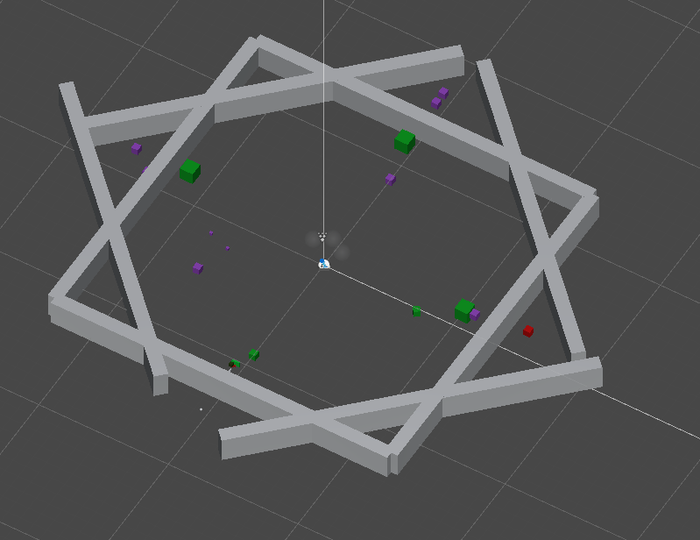

Another benefit of leaning on binaural audio was that it allowed Evans to draw on his existing design expertise and construct The Vale in 3D space. Though you might never know it given the only visuals in the game are swirling particle effects designed to help sighted players, everything in The Vale was originally built to scale.

"Everything is physically in 3D space," Evans tells me. "That was another important thing that we did, because I didn't know where else to start. I just set everything to scale. I wasn't thinking of using any kind of smoke and mirror techniques, or messing with pans or something. This is what binaural audio does. It gives you precision, because you can hear the difference -- not just right and left -- but at 45 degrees and so forth.

"That's how we built the world. I set the height of the player's head at the height of an average person, and I placed the enemies so they'd be talking from their head, or so their footsteps would emanate from their feet -- because again, I don't know what the fidelity of these things would be, so when they're 20 feet away I put them 20 feet away."

A look at the editor used to build The Vale

Once he'd set the stage, Evans then made minor adjustments for playability. So, for instance, if players needed to hunt a rabbit that was 20 feet away but might scarper and end up 40 feet away, he had to create a tail-off effect that could easily be tracked.

"I had to have some audio elements not drop off as quickly, then others I wanted to fall off really quickly because proximity matters," he continues. "So if you're near something dangerous, I don't want you to hear it when it's far away. I want you to hear it when you get close. So I had to start making sounds behave unnaturally for these very specific design reasons, but everything started like I was shooting a movie and placing things."

As we discuss the challenges of creating a game free of visuals, our conversation touches on one of the inherent positives: accessibility. Although Evans didn't set out to make a game for those with visual impairments (initially, it was simply a genre he wanted to explore), the director quickly began working with consultants from that community -- such as the Canadian National Institute for the Blind -- to ensure The Vale would be as inclusive and accessible as possible.

Evans explains how one of the biggest benefits of working with the visually impaired community was being able to learn from their experiences. Being a sighted developer, they could share insights that Evans might not have considered, allowing him to make the game more accessible by simply taking the time to listen.

New perspectives mean better games, says Evans, who wonders if larger studios are more cautious when it comes to accessibility out of fear of getting it wrong. "I think the fear is, and this is my guess, that bigger companies are afraid to step out halfway and say 'hey, look, we made an attempt' and people are like 'no, that was a terrible attempt.' I look at The Last of Us Part II, and pretty much across the board people said they hit it out of the park. They did a lot of great things, and that's probably something all big, big titles should be looking at," he adds.

"It would be nice if everyone could afford that, but I would [tell other devs to] look at how close are you to already being there with what you already do and care about, and then look at the small things. That's something I was reminded of very early on by one of my consultants. He had just played a game with his wife, and he said there was just one change that needed making in order for him to play the game. [So while] I think there are legitimate conversations and debates to be had [with regards to accessibility], it'd be nice if every company assessed their game in search of those little changes that could make a huge difference."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like