Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Sports commentary is an essential part of the viewing experience -- thus core to the game industry too. How to write it right, from Madden vet Ernest Adams.

When I was at Electronic Arts, I spent about six years doing audio and video production for the Madden line of American football games, and that included planning, writing and recording the artificial broadcast commentary that accompanied the game. Televised sports commentary is normally done by two (sometimes three) people, and we were trying to duplicate that experience in the game. One person, the play-by-play man, gives the description of the game itself, while the other, the color commentator, provides additional information and insight. In our case John Madden was the color commentator and Pat Summerall -- his CBS Sports broadcasting partner at the time -- provided the play-by-play. In this column I'm going to talk about how to go about writing this material based on my own experience.

Before I get into it, I need to make two suggestions. First, this column is only about planning and writing; it's not about recording and editing. If you'd like to know more about the recording side of things, read my article "Putting Madden in Madden: Memoirs of an EA Sports Video Producer." It's not really a how-to piece, but it does give a feeling of what was like to be there, along with some background you may find useful.

Second, I'm not going to address the complicated issue of writing interchangeable dialog content -- that is, stitched-together sentences in which the software inserts names, numbers, and other information as the sentences are being played aloud. Correctly writing and recording interchangeable content is a huge part of creating sports commentary, but I've already described it in great detail in Chapter 13 of the book Game Writing: Narrative Skills for Videogames, edited by Chris Bateman. If you're going to write sports commentary with interchangeable content, I strongly suggest that you buy the book and read that chapter (and before you ask, no, I don't get royalties).

Sports games come in many different flavors. They can be about real sports or imaginary ones; they can be arcade-like or serious simulations; they can be cartoony or photorealistic. The style of your game will affect your decisions about the commentary.

Cartoony arcade sports games usually have simple, repetitive, rather loud voiceover audio that simply announces the results: "Strike three!" "Home run!" and so on. These are easy to write for; they're just sound effects that accompany key in-game events. You're not really trying to create the illusion of broadcast commentary at all.

Assuming that you are planning to simulate real commentary, the next question is, are you only going to do the play-by-play, or will you do color commentary as well? They're very different. Play-by-play is a description of the game as it happens. On the whole, it's fairly easy to hook the audio into the game engine to generate the appropriate playback for each event: When a team scores a goal, you play an appropriate clip. Color commentary requires considerably more artificial intelligence, because the game has to make insightful remarks about the game, teams, and players. I'll handle each of these separately in later sections.

Another important decision is, TV-style or radio-style? Real TV commentary is nowhere near as detailed as radio commentary, because the viewers can see what's going on. Radio commentary is a real art, trying to convey the action on the field in words, just as quickly as it happens. On TV, an American football play might sound something like this: "Third and seven. Here's Kerry. Play-action... over the middle and it's knocked down by Levy." On radio, the same play might sound like this: "Third and seven on the Giants' own 42. Split backs, Johnson wide to the right. Bengals in a nickel package. Kerry steps up, takes the snap, fakes a handoff to Thomas but nobody's fooled, fires over the middle to Carter, the big tight end, but it's knocked down at the line of scrimmage by Levy, and the Giants will have to punt."

You can see how much more work is involved in radio-style commentary. While I was working on Madden we didn't try to do radio-style, partly because John Madden was a TV broadcaster and we didn't feel it would be appropriate, and partly because it would have required so much more code and a longer recording script. Madden himself is a color commentator, so the decision didn't affect him, but his play-by-play broadcasting partner at the time was Pat Summerall and he would have had to do all the recording for radio-style play-by-play. We only got a few days each year to work with them and it was an expensive process. After I left, the Madden team at EA decided to try something that they called radio-style commentary for a few years, but it was widely disliked and they abandoned it again for Madden NFL 09.

You can see how much more work is involved in radio-style commentary. While I was working on Madden we didn't try to do radio-style, partly because John Madden was a TV broadcaster and we didn't feel it would be appropriate, and partly because it would have required so much more code and a longer recording script. Madden himself is a color commentator, so the decision didn't affect him, but his play-by-play broadcasting partner at the time was Pat Summerall and he would have had to do all the recording for radio-style play-by-play. We only got a few days each year to work with them and it was an expensive process. After I left, the Madden team at EA decided to try something that they called radio-style commentary for a few years, but it was widely disliked and they abandoned it again for Madden NFL 09.

Your scope may be limited by the amount of code it will take to support commentary, the amount of time you have to record your voice talent, or both. If your game is new your programmers will naturally be spending the majority of their effort on building the game engine, tuning it, and fixing bugs. They will -- rightly -- see the commentary as a cosmetic feature which mustn't get in the way of the actual gameplay. This is not an excuse for doing a rushed, sloppy job, however.

If you're writing a script for the first time, you can skip this step. But if your company has ever released a previous edition of your game, get hold of the design documents and find out what they did before you got involved. This is even more important if your team is updating existing program code, because the code will already have the hooks in it to deliver audio. Talk to the programmers about what's already in there, and discuss what you'd like to do to update it.

In my case, I was writing the play-by-play for the first CD-ROM version of Madden. All the earlier editions had been distributed on cartridges or floppy disks, so the audio content was minimal. Still, I got the documents from the Sega Genesis version of the game to familiarize myself with the voiceover.

You may think you know what TV sports broadcasting sounds like, but nothing is as enlightening as recording and transcribing one word-for-word. It will give you a sense not only of how these broadcasts work, but also -- and even more importantly -- the vocabulary and manner of your voice talent. For us, it was imperative that John Madden and Pat Summerall sound like their real-life selves in the game, and the best way to achieve that was to study them at work.

I had an assistant producer sit with a videotape (it was that long ago) of three different games that had been broadcast by our stars, and type in everything they said. We didn't bother with the pre-game or post-game shows, only from the introduction to the game itself to the final score. Because it was American football, the game neatly broke into plays, and my assistant typed the results of each play, as well as the time remaining on the clock, in among the commentary. Here's a sample from a Tampa Bay-Green Bay game:

3-9-TB30 (2:00) T.Dilfer sacked at TB26 for -4 (G.Wilkins). [I.e. 3rd down and 9 yards to go on the Tampa Bay 30 yard line, 2 minutes remaining in the quarter; T. Dilfer sacked at the Tampa Bay 26 for a loss of 4 yards, by G. Wilkins.]

S[ummerall]: Here's Dilfer back to throw... pocket collapsed, and down he goes, as Gabe Wilkins gets there.

M[adden]: Old Gabe Wilkins is havin' a heckuva day.

S: Isn't he?

M[Telestrator, Circles Wilkins]: Tell ya, he was the guy, course, got that, that interception for the touchdown, and the great run, and the great jump, and here, he's gets a pass rush over Tampa Bay's best offensive lineman. That's their left tackle, Paul Gruber. [Wilkins' stats appear] He just got Gruber goin' back, and then he just he came right off of him, and made the, made the sack on Dilfer. He doesn't watch out, he's gonna be NFC defensive player of the week.

S: Maybe of the month.

M: Yeah, because when you get numbers like that, you know, and that's what every defensive lineman wants is, is numbers. And of course you get the sack numbers. But then, when you get the interception numbers, and the interception for a return numbers, now you're talkin' numbers, now you're talkin', you got some numbers.

S: Green Bay just took a timeout, stopped the clock. Tommy Barnhardt, back to punt. And he's done well against the wind.

In a more free-flowing game you'll just have to note key events when they occur, to indicate what the commentators are actually taking about.

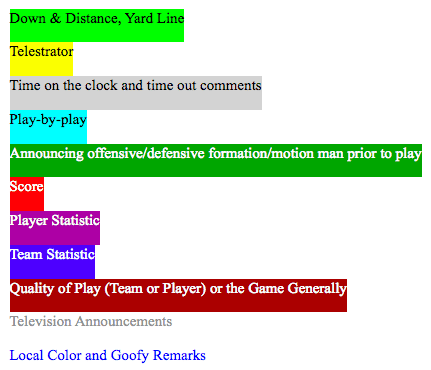

The next thing to do is analyze the transcript, dividing the speakers' sentences into categories depending on the subject matter. You're looking for particular patterns of commentary, remarks that occur regularly. I loaded the transcript into Microsoft Word and marked it up using the highlighter and font color features. Each color designated a different category of speech. The categories I came up with for our game were

The Telestrator is a device that lets a commentator draw on top of the TV image; it was one of John Madden's specialties and I'll address it later. "Television Announcements" refers to advertising -- "Watch 60 Minutes on CBS tonight."

I didn't duplicate these in the game, but I did want to see how often they occurred. "Local Color and Goofy Remarks" (Mr. Madden was famous for the latter) means comments on the weather, the city, the state of the field, or anything interesting but outside the game itself.

Here's the sample I gave earlier, marked up using the system above:

I highlighted the items that I felt fit into the categories I was looking for. I didn't expect to reproduce any of this material exactly in the game, I just wanted to study the way the broadcasters spoke when discussing particular circumstances, events or issues.

You'll notice that a certain amount of this isn't highlighted at all. That's material that I judged we simply wouldn't be able to get into the game. For one thing, a video game of football goes much faster than a real game, so there's little time for rambling commentary like Madden's remarks about how defensive linemen want to get numbers. In practice, no sentence could be longer than about 20 seconds at the very most, and we tried to keep them down to 5 or 10.

Obviously the categories you decide on will depend on the sport. You won't necessarily find everything you need by looking at the transcript, because not every event happens in every game. For example, I didn't have a highlight for discussing injuries, because none occurred in the transcripts I was working with. Nor did I have a highlight for announcing penalties. In the NFL the referee on the field announces penalties, so that content belongs in the referee's audio script, not in the commentators'.

Your development team should already own a copy of the sport's official rule book; if it doesn't have one, buy one. As I said, many of the events that can occur in a game won't necessary happen in the ones you transcribe. It's your job to have commentary for every event that can possibly happen within your video game. Fortunately, the number of these is somewhat smaller than the number of events that can happen in a real game. You don't need any comments about a fan interfering with the game, for example, unless for some reason you implement such an event. Here's a little flow chart showing the possible outcomes of a corner kick in soccer:

The programmers will have to implement code for each of these circumstances, and you will need appropriate commentary as well. The chances of a kicker in a corner kick handling the ball inside the penalty area before anyone else touches it is pretty remote, but you can bet that your players will try to make it happen if they can. If they succeed, your commentators should have something to say about it.

Sit down with the game's designers and programmers and consult with them about how much of the rule book will be implemented in the game. Rule books are full of truly arcane rules for circumstances that simply can't happen in a video game. For example, if a base coach deliberately interferes with a thrown ball in baseball, the runner is out. Many baseball games don't include base coaches at all; in those that do, the players have no way of controlling them, so there's no way to intentionally interfere. The base coaches are just cosmetic and could even be transparent to baseballs so as not to interfere with them.

Finally, don't count on the rule book for everything. You'll need to write commentary for events that the rules don't cover, such as naming the players as they come out on the field at the beginning of the game. This is why you need both a transcript of a real game and the rule book to tell you what you'll need to write.

At this point, you know the scope of your project -- whether you're doing radio-style or TV-style commentary, and so on. Using any prior script that may exist, your transcript of a real game, and the rule book, you should now work out a list of events that you want to write commentary for. Verify with the programmers that they are planning to implement all these events and can detect when they occur in the game.

You will need to create events both for the play-by-play and the color commentary. The play-by-play events will naturally come from the actual activity in the game, while the color commentary will apply both to particularly noteworthy events and to the failure or success of the player's strategy and tactics. For example, you might have play-by-play commentary for an intercepted pass, and color commentary for the situation in which a team has had four or more intercepted passes in the course of the game. A single interception deserves a certain kind of comment, while a string of them needs something different.

Here, as an example, is a list of just a few of the events we could detect in one edition of Madden. These are all from the section of the script devoted to running plays:

Long run -- resulting from many missed tackles

Long run -- not resulting from missed tackles

Run up the middle for short gain

Outside run for short gain

QB keeper -- resulting in gain

QB keeper -- resulting in loss (not a sack)

Goal line touchdown dive -- successful

Goal line touchdown dive -- stopped

I left it up to the programmers to decide what exactly constituted "many missed tackles." In some circumstances I wrote pseudo-code to explain exactly what should trigger a particular event.

If your voice talent consists of famous (and therefore expensive) broadcasters, as ours did on Madden, you may have only a limited amount of time to record them. In that case, you can't write too much material and you'll have to sort your script with the highest-priority items at the beginning. These should be the most common events in the game: routine play. Leave the material for more unusual events (a no-hitter in a baseball game, a tied final score in a basketball game) for later.

Now you need to write the play-by-play -- the actual account of what's going on -- for each event in the game, including the welcome and goodbye remarks, introducing the starting players, and everything else. For commonplace events that happen over and over, you should write many different versions so the players don't get tired of hearing it, as many as ten or twenty. This can be difficult to do -- there are only so many ways to say "strike three."

Here are some sample lines for one particular event -- a deflected pass:

I think the defender just barely got a hand on it.

He knocked it down.

Trent [knocked it down.]

Trent [with the knockdown.]

The defender got his hand in there to knock the ball down.

Tipped away.

It's tipped away.

Trent [tipped it away.]

Lines with square brackets in them indicate interchangeable content -- the name "Trent" would be removed during the editing process and the correct name would be inserted during playback in an actual game. You'll need to do this for names of players, teams, cities, stadiums, and a wide variety of numbers -- those used for the score, time remaining, and so on. Again, see Chapter 13 of Game Writing for details on how to construct this content.

Madden and Summerall's division of labor in the broadcast booth was not strict, so we wrote some play-by-play for John Madden too.

Once you've written the play-by-play, write the color commentary. Color commentary is much trickier, because rather than simply describing game events, it has to sound like intelligent analysis after the fact. As you saw from my marked-up transcript, I noted remarks about particular players or the team in general. Of course, whatever you write has to be generic and work during any given game.

We didn't try to do interchangeable content for the color commentary. Pat Summerall's voice has a very steady, even inflection which made it easy to stitch his words together into sentences. John Madden's voice has much more dynamic range, so we decided not to try it. This meant that (except as explained below), his comments couldn't include the names of teams. We had to use "these guys," "they," "the offense," and similar generic terms. Here are some example lines for the circumstance in which a team has failed convert on 4th down (rather than punt or kick a field goal), and failed more often than it has succeeded in the current game:

They haven't had much success on fourth down today, at some point you gotta wonder if going for it is actually worth the risk.

If you don't make it on 4th down, you give a lot of momentum to your opponent.

This offense hasn't had too much success converting on 4th down today.

Getting stopped on a 4th down conversion swings a lot of the momentum to the opposing team.

When you get stopped on a 4th down conversion attempt like that, you often second-guess yourself and think that you should have punted or kicked the field goal.

During the writing process my assistant producers identified 5-10 star players on each NFL team, and they wrote four or five special lines of dialog about each of them, which Mr. Madden recorded. The marketing department called this feature "Star Talk." Each line would cover some aspect of the player's abilities -- power, speed, or simply the quality of being exciting to watch. We also included unusual anecdotes, if there were any.

Whenever one of the star players was involved in a particularly big play during a game, the software would try to choose the most suitable line to play for him. The programmers made sure each line was only played once per game. It would obviously sound ridiculous if Madden said exactly the same remark twice in a game. As a general rule of thumb, the longer the line of dialog, the less frequently the player should hear it.

In addition to the Star Talk, we also recorded general comments about the teams themselves, particularly for use at the beginning of the game when they were being introduced. Because John Madden is an especially colorful broadcaster, we were able to create material on all kinds of things, including his thoughts about the weather, stadiums, and even the kinds of food that particular cities were famous for.

Once you have everything written, sit down with the other people on your team and read through everything aloud so everyone can hear what it's supposed to sound like. You'll need to check for a variety of possible errors:

Missing content. Are there any important game events that you forgot to include? Are there team or player names, or numbers, that are missing from the script?

Unusable content. There's no point in recording material for events that are too complex or improbable for the programmers to detect. Normally you should have checked these with the coding team before starting to write the dialog, but double-check them again now.

Improper vocabulary and style. If you write a word or a line that your talent would never use, you reduce the total material you have and waste precious time in the recording session.

Grammar and spelling mistakes. Again, these will trip up your talent during the recording session and waste time.

That includes the step-by-step portion of the process. I want to address two more issues, interruptions and the Telestrator.

Occasionally, something dramatic happens in a sports game that causes a play-by-play commentator to interrupt what he was saying and change topics to address the new event. In a video game, we play back audio clips of a fixed duration, and if we want to switch to a different clip in the middle of playback, there will be a noticeable pause as the disc seeks to the new clip. It also won't sound like a smooth transition in the speaker's voice. To cover this, you can record your color commentator making a variety of short generic exclamations ("Wow!" and "Did you see that?" etc.) and keep them in RAM. When something happens that merits an interruption, play back an exclamation over the top of the play-by-play man, which will hide the seek time and provide the break needed.

A Telestrator is a device that lets a commentator draw lines on top of the broadcast image, and John Madden is famous for using one to analyze football plays. When I went through the transcripts of the recorded games, I highlighted Madden's comments as he was using the Telestrator.

Because it's one of the things Madden is so well-known for, I was interested in trying to create a simulated Telestrator as part of the color commentary. After all, we knew what play both teams had called, where each athlete had gone and what the outcome was, so it would not have been difficult to draw circles and arrows on the screen to illustrate the results after the fact. The trick would have been getting the dialog right, and it would have required a great deal of broadcaster AI. Above all, it was essential that it work correctly; if it made a mistake, it would have made Mr. Madden look stupid, and we didn't want that.

In the end we never implemented it while I was there. It was not a high-priority feature and the additional coding workload was not worth the effort. The recent Wii games let the players draw on the screen, and Madden NFL 09 offers an automated Telestrator that comes up when the player makes a mistake to show what he should have done, but it doesn't include Madden's unique narrative style. That was what I had really hoped to supply.

If you're going to do Telestrator commentary, first figure out which events what you want to illustrate. Normally they'll be things that were either very good, very bad, or very unusual. Then you'll have to write commentary to describe the event, again using interchangeable content to supply the names of players. (In Madden's case I would have simply used "this guy" or the name of the player's position -- defensive end, etc. -- because we didn't try to have Madden record interchangeable content.)

Interesting, accurate sports commentary is an integral part of the experience for serious sports simulations. Although it's necessarily less important than gameplay, a modern game would feel wrong without it. The early sports games were infamous for providing too little material, and players would often turn it off to avoid hearing the same dialog over and over. To do it right, start early, devote someone to it full-time, write masses of material -- as much as you can afford to record -- and check and double-check everything. The ideal result is a game that is indistinguishable from the real thing to a listener with his eyes closed.

Attention friends and fans: the next Designer's Notebook column will be "Bad Game Designer: No Twinkie X" -- number 10 in my long-running series of game design gripes and gaffes. Check out the No Twinkie Database and then, if you've got a new one, write it up and send it to me at [email protected].

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like