Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

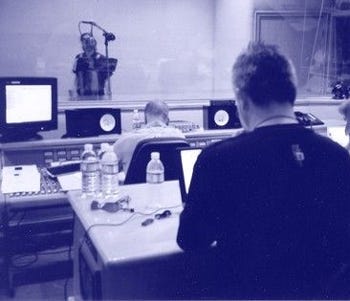

In today's audio-focused feature, former Midway and current Obsidian audio director Alexander Brandon looks at how game audio specialists can find help for vital audio implementation tasks, when the crunch is on.

All too often, video game audio teams can find themselves with an awful lot of work to do, and not enough people to do the work. Let’s find a potential solution to this problem and start with the symptoms. When does this happen and why?

Alpha

VO sessions

Demos / internal reviews

You need to establish a final mix (as well as last minute sound design and implementation) for multiple platforms each with their own hardware and sound engines

VO sessions start next week and you signed up to edit everything yourself because you’re “incredibly fast”

You’ve finally found time to update vital asset lists and sound design documents when a big demo comes along and you need to dress it to impress

Post-production doesn’t exist in game schedules. Often there is less than a month of time from when game assets are finished to when all content including code needs to be locked down for release candidate testing.

It’s easy to assume that you’ll need extra hands to assist with parallel tasks to achieve a goal within a certain time frame. However sitting down and figuring out details and flowcharts most likely isn’t in your schedule. Still, I can’t underestimate how freaking important it is to differentiate between the need for a full time employee and a temporary one. And with the exception of the last “Why” reason -- the lack of a post-production phase in games -- there’s a way to tackle the issues without adding to full time employee headcount. Unfortunately the latter reason is a whole article unto itself (and probably the most significant one) but it's a topic for later.

Take a look at how several companies hire and fire. Speaking fairly, sometimes this just happens even with the best of planning. But identifying long term needs is critical to establishing just how far you will require a service and the ability to budget for it. Most of the time however, Alpha only lasts a few months (even less for PC or single platform titles), VO sessions around the same (far less for projects with fewer than 10,000 lines), and sometimes racing towards a demo can only last a few weeks.

In some cases you may have a list of contacts locally that can assist with a variety of tasks. Nowhere is this truer than Los Angeles, but creative managers can seek candidates for temporary work in local colleges and even high schools.

In the event that you don’t have a line of people ready to help for any amount of time and a legal department or administrative assistant that can help write up contracts for each and every situation, there’s another option: QA and associate producers.

In almost every QA department there’s someone dying to get their hands on game audio. Use this to your advantage. QA has downtime like everyone else, and a task that can fill that time is audio training. Tasks and skills such as the following can be taught in a single day:

(top and tail, normalization, basic and relative mixing)

This entire process should take less than two hours. Sound Forge costs around $300, and Sound Forge Audio Studio (the equivalent of Photoshop LE) is a mere $70. Get your trainee a copy of one of these programs and go to work. Simply grabbing a section of the file with space in it and deleting it is easy. Selecting mouth noise and pops, and then muting them, is also easy to grasp. After that, using the normalization tool helps set the proper volume, but keep in mind relative volume (if you normalize a whisper, for example, it will sound much louder than a yell). In most cases you’ll need to edit volumes of each file until they’re all somewhat similar. Add to this the general rule that 3db up or down is the smallest perceived volume change, add 20 minutes of practice with a dozen sample files, and you’ve got yourself a junior audio editor.

Sound Forge (the $300 version) comes with a batch converter. Sometimes you’ll need a mass amount of WAV files converted to MP3s, OGG, or AAC. The batch converter couldn’t be simpler: just select your files and teach your trainee about what formats they need to use (stereo / mono, bitrate, sampling rate, etc.) When you’re in the midst of something a little more demanding on your own experienced ear and you require a lot of conversion, you’ll have someone who is happy to oblige.

This conversion can work for groups of sounds that require volume tweaking for a better mix (although ideally this should happen as a function within your game engine). It can work well also when you need to save memory, though fortune will one day bless audio designers with the ability to have only 44.1khz sounds and up in an asset heavy title, just as it will allow texture artists to use nothing but 512x512 textures.

(does a file actually trigger properly?)

Which build needs to have what files? Are they all present? What about the exponentially higher amounts of VO for localized versions? Again, these questions are important, but not critical in actually making the game more fun. If that is your job, you needn’t worry about these questions and they’re best dealt with by someone else.

If you don’t have a contractor doing all these things for you already, then document the information required in spreadsheets and other formats to the point where you’re sure they’re right. This will allow you to pass off scripts and sound asset lists to your QA audio specialist and have them go to town. Time may come soon where missing audio files become a TRC violation. Don’t wait until that happens.

A key component of this plan is remembering that QA usually kicks into high gear in Alpha and top gear in Beta, so planning ahead with the QA supervisor well in advance of both the training sessions and when you will need them is important. Earmark an audio specialist and ensure that the QA department is aware of their role.

How often can an audio team sit down and play through the game it is creating the audio for, to make sure that all VO, physics and UI sounds are triggering in every possible instance that they are supposed to? Supply the script and approximately four hours for every five hundred lines (or substitute sound effects) to test, and you’ve got yourself a solid VO testing plan.

A/B comparison demonstrations to the QA team in general also yield significant results. For example, demonstrating a good mix in a cinematic and then a bad mix (one audio part is too loud, etc.) helps train these young ears not only for potential help with audio tasks on a project, but also for when the time comes to test the game itself. Generate a checklist for QA to run through to ensure the audio quality is where you and the team (and the publisher!) want it to be so there is no doubt.

After all the training and documentation is established, when the time comes and you find yourself shorthanded, ask whoever manages QA at your company if there are any spare bodies to assist. If you have prepped them you should have a much better chance of getting that help. As a bulk of development typically comes before the QA process begins in earnest, managers typically smile on the use of a less expensive resource already in the company.

Another great resource to use is associate and assistant producers. I find that these guys and gals are very underutilized and often are only assisting with documentation work, driving the game at internal reviews and trade shows, helping with the build process, etc. In reality their best asset is the likelihood that they have authority to enlist multiple staff resources if a problem arises.

For example, suppose an associate producer is tasked with helping implement audio. If you train the producer with the skills mentioned above in a day session, they should already have the ear to test the audio they need to implement, but if there is a blocking problem that is code related they (usually) have authority to enlist the help of a programmer -- whereas a member of the QA department probably does not.

There really are plenty of alternatives to hiring and firing, and potentially saving money doing it by using required skills as a temporary resource only when necessary. I hope this methodology finds its way into your workflow, so you stop pulling out your hair trying to get the audio sounding slick while trying to take care of the supporting tasks as well.

You May Also Like