Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This article shares music production tips from the GDC 2016 talks of Laura Karpman and Garry Taylor. I've also shared practical examples from my experience composing for live orchestra for the Ultimate Trailers album (including listening samples).

I was pleased to give a talk about composing music for games at the 2016 Game Developers Conference (pictured left). GDC took place this past March in San Francisco - it was an honor to be a part of the audio track again this year, which offered a wealth of awesome educational sessions for game audio practitioners. So much fun to see the other talks and learn about what's new and exciting in the field of game audio! In this blog, I want to share some info that I thought was really interesting from two talks that pertained to the audio production side of game development: composer Laura Karpman's talk about "Composing Virtually, Sounding Real" and audio director Garry Taylor's talk on "Audio Mastering for Interactive Entertainment." Both sessions had some very good info for game composers who may be looking to improve the quality of their recordings. Along the way, I'll also be sharing a few of my own personal viewpoints on these music production topics, and I'll include some examples from one of my own projects, the Ultimate Trailers album for West One Music, to illustrate ideas that we'll be discussing. So let's get started!

I was pleased to give a talk about composing music for games at the 2016 Game Developers Conference (pictured left). GDC took place this past March in San Francisco - it was an honor to be a part of the audio track again this year, which offered a wealth of awesome educational sessions for game audio practitioners. So much fun to see the other talks and learn about what's new and exciting in the field of game audio! In this blog, I want to share some info that I thought was really interesting from two talks that pertained to the audio production side of game development: composer Laura Karpman's talk about "Composing Virtually, Sounding Real" and audio director Garry Taylor's talk on "Audio Mastering for Interactive Entertainment." Both sessions had some very good info for game composers who may be looking to improve the quality of their recordings. Along the way, I'll also be sharing a few of my own personal viewpoints on these music production topics, and I'll include some examples from one of my own projects, the Ultimate Trailers album for West One Music, to illustrate ideas that we'll be discussing. So let's get started!

Laura Karpman (pictured left) gave a talk on the first day of the conference, as a part of the Audio Bootcamp track of sessions. As a film and game composer, her most recent credits include the video game Project Spark and the WGN America cable TV series Underground. Her talk focused on improving the quality of music recordings that use MIDI and sample libraries to simulate a full orchestra. Early in the presentation, Karpman reminisced about the time when her clients would come to her studio to hear early sketches of her work. Those times are long gone, she told us. "Even when you're going to record an orchestra or record any number of musicians, your demos have to leave your house sounding great because nobody will be able to imagine what they're going to sound like."

Laura Karpman (pictured left) gave a talk on the first day of the conference, as a part of the Audio Bootcamp track of sessions. As a film and game composer, her most recent credits include the video game Project Spark and the WGN America cable TV series Underground. Her talk focused on improving the quality of music recordings that use MIDI and sample libraries to simulate a full orchestra. Early in the presentation, Karpman reminisced about the time when her clients would come to her studio to hear early sketches of her work. Those times are long gone, she told us. "Even when you're going to record an orchestra or record any number of musicians, your demos have to leave your house sounding great because nobody will be able to imagine what they're going to sound like."

I appreciated Karpman's advice to begin each project by getting thoroughly acquainted with our orchestral libraries and arranging our instrument choices meticulously. That's a working method that I've also followed throughout my career. Exploring the depth and breadth of our sound libraries at the beginning of a project is crucial towards understanding where we might have gaps in our libraries that need to be filled. I discuss the process of acquiring new virtual instruments during a project in my book, A Composer's Guide to Game Music (pg. 131). I also discuss the many ways that we can maximize the realism of our virtual instruments (starting on page 224).

Karpman covered some of the same ground during her presentation. At one point she reminds us that virtual instruments must behave the way real instruments would. "People breathe," Karpman points out. "If you are writing a flute line that is continuous and there's no room for breath, it's not going to sound real." While acknowledging that it's important for us to stay on top of technological developments in virtual instrument software, Karpman encourages us to also stay in touch with the realities of acoustic musicianship and the real-world capabilities of each orchestral section.

Karpman covered some of the same ground during her presentation. At one point she reminds us that virtual instruments must behave the way real instruments would. "People breathe," Karpman points out. "If you are writing a flute line that is continuous and there's no room for breath, it's not going to sound real." While acknowledging that it's important for us to stay on top of technological developments in virtual instrument software, Karpman encourages us to also stay in touch with the realities of acoustic musicianship and the real-world capabilities of each orchestral section.

One of Karpman's observations that I found particularly interesting pertained to her workflow from the MIDI stage to the orchestral recording stage. "My Pro Tools session went to the copyist," she shares, detailing her process of delivering MIDI mock-ups to an orchestrator who would transcribe the parts for performance by live musicians. Describing this process, Karpman takes a moment to extol the virtues of the ever-famous Pro Tools software. "The thing I love about Pro Tools is it equates audio and MIDI," she says. "There's no big differentiation. You can drag a MIDI track right up to an audio track, copy, look at them next to each other, blend them together," she observes. "A Pro Tools session - you make a mix of it, and it goes to the copyist. Why? Because it's brilliantly organized."

One of Karpman's observations that I found particularly interesting pertained to her workflow from the MIDI stage to the orchestral recording stage. "My Pro Tools session went to the copyist," she shares, detailing her process of delivering MIDI mock-ups to an orchestrator who would transcribe the parts for performance by live musicians. Describing this process, Karpman takes a moment to extol the virtues of the ever-famous Pro Tools software. "The thing I love about Pro Tools is it equates audio and MIDI," she says. "There's no big differentiation. You can drag a MIDI track right up to an audio track, copy, look at them next to each other, blend them together," she observes. "A Pro Tools session - you make a mix of it, and it goes to the copyist. Why? Because it's brilliantly organized."

As a long-time Pro Tools user, I completely agree with Laura Karpman about the versatility of the software. Pro Tools is tremendously convenient for a composer who likes to combine MIDI and audio work frequently in the same session. It's also very easy to share Pro Tools session data with our colleagues, since Pro Tools is such a popular and ubiquitous software application in the game audio community.

On a more personal note, I've had several opportunities to record with live musicians, and I thought it might be useful at this point for me to include some of my own live orchestral music (along with the MIDI mock-ups) for the sake of providing a concrete example. With that in mind, I'd like to share some personal observations about recording with an orchestra for tracks I composed for the Ultimate Trailers album (pictured left), released by the West One Music label. I'll be using as an example my Ultimate Trailers track, "Valour," which was performed by the AUKSO Alvernia orchestra.

On a more personal note, I've had several opportunities to record with live musicians, and I thought it might be useful at this point for me to include some of my own live orchestral music (along with the MIDI mock-ups) for the sake of providing a concrete example. With that in mind, I'd like to share some personal observations about recording with an orchestra for tracks I composed for the Ultimate Trailers album (pictured left), released by the West One Music label. I'll be using as an example my Ultimate Trailers track, "Valour," which was performed by the AUKSO Alvernia orchestra.

First, a little background info: the AUKSO Alvernia orchestra (pictured below) has been named as one of Europe's foremost ensembles, and is led by eminent violinist and conductor Marek Moś.

The Ultimate Trailers album was designed to be a collection of hard-hitting, epic orchestral tracks for use in television and film. Since its release, the music I composed for Ultimate Trailers has been featured in popular sports programming such as NBC football, FOX Major League Baseball and the PGA Championship.

When I first composed the "Valour" orchestral track, I worked in my studio (pictured below) primarily with MIDI libraries (including instruments from such libraries as East West Symphonic Orchestra, Vienna, Hollywood Brass, LA Scoring Strings, etc).

I worked hard to emulate the sound of a live symphonic orchestra for my MIDI mock-ups. As Karpman observes, it is imperative to demonstrate the proposed sound of your final piece as faithfully as possible in your MIDI mock-up. The only live element in my MIDI mock-up recording for the "Valour" track is the full choir, which I recorded by overdubbing my own voice many, many times. Here is an excerpt from that initial mock-up recording:

Now, here is the final version, as recorded by the AUKSO Alvernia Orchestra. You'll notice that while the orchestral version has qualities of texture and timbre that reveal its nature as a live recording, the MIDI mock-up did a pretty good job of emulating the sound of a live orchestra. Plus, my live (overdubbed) vocal choir from the mock-up recording was retained for the final version of the track - it was combined with the live orchestra to achieve the result that you'll hear in the following excerpt:

Creating an effective MIDI mock-up depends greatly on our understanding of the mechanics and artistry of the actual orchestra. Laura Karpman's GDC talk is an interesting exploration of an important topic for any video game composer. For those of us with access to the GDC Vault, the entire video of Karpman's session is available here.

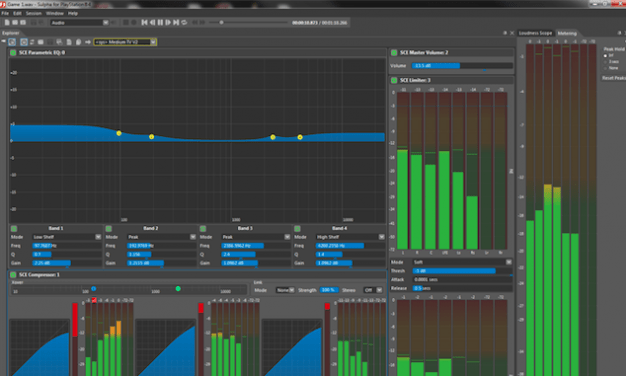

Garry Taylor (pictured left) is an Audio Director in Sony Computer Entertainment Europe's Creative Services Group - a division of the company that designed and manufactures the PlayStation console. In that capacity, Taylor gave a presentation at GDC 2016 that extolled the virtues and benefits of the proprietary PlayStation 4 Audio Mastering Suite. The PS4 Mastering Suite is built into the game console, and its capabilities are available to all developers for the PlayStation system by virtue of an accompanying software package. Named "Sulpha," (pictured below) this signal processing application includes a four band parametric EQ, a three band compressor, a simple gain stage, and a peak limiter. All of these tools are meant to accomplish a simple yet very important task - to enable developers to adhere to a consistent loudness standard across all titles developed for the PlayStation console.

Garry Taylor (pictured left) is an Audio Director in Sony Computer Entertainment Europe's Creative Services Group - a division of the company that designed and manufactures the PlayStation console. In that capacity, Taylor gave a presentation at GDC 2016 that extolled the virtues and benefits of the proprietary PlayStation 4 Audio Mastering Suite. The PS4 Mastering Suite is built into the game console, and its capabilities are available to all developers for the PlayStation system by virtue of an accompanying software package. Named "Sulpha," (pictured below) this signal processing application includes a four band parametric EQ, a three band compressor, a simple gain stage, and a peak limiter. All of these tools are meant to accomplish a simple yet very important task - to enable developers to adhere to a consistent loudness standard across all titles developed for the PlayStation console.

While all of these details about Sulpha (pictured above) were fascinating, and were explained in detail during Taylor's GDC talk, I found myself particularly interested in Taylor's ideas about the nature of audio mastering itself. He expressed many firm opinions about the most desirable goals of the mixing and mastering process. He also described methodologies for achieving the best end results. Since many video game music composers are also responsible for the mixing and mastering of their own recordings, I thought that an exploration of Taylor's ideas on this topic could be very helpful to us.

"Mastering for me is about preparing the audio content we create for the device on which it's going to be listened to," Taylor observes during his GDC presentation. "As I say, this could range from a kick-ass surround system down to a small phone. Now, because the frequency response of all these different types of systems are very different, in an ideal world we need to adjust the timbre and dynamic range of our content to suit these different speaker systems from the very large to the very small."

Taylor also emphasizes an important differentiation between mastering and mixing (pictured right). "They are two very different processes, and for a very good reason," he tells us. "Mixing is preparing all of those separate elements in the title and making sure they all work together and don't get in each other's way. Artistically, it's about focus. It's about focusing the player on what you feel as an audio developer is important at any point during your game. Technically... it's about achieving a certain level of clarity. Mastering is about preparing all that mixed content for a specific playback system or scenarios where the end user (the gamer) needs limited dynamic range."

Taylor also emphasizes an important differentiation between mastering and mixing (pictured right). "They are two very different processes, and for a very good reason," he tells us. "Mixing is preparing all of those separate elements in the title and making sure they all work together and don't get in each other's way. Artistically, it's about focus. It's about focusing the player on what you feel as an audio developer is important at any point during your game. Technically... it's about achieving a certain level of clarity. Mastering is about preparing all that mixed content for a specific playback system or scenarios where the end user (the gamer) needs limited dynamic range."

Taylor warns us that when we're mixing our work with very high-end equipment and monitors such as a surround system (pictured left), we may end up with mixes that sound significantly sub-par when they're fed through lower-grade speakers. This effect may be especially pronounced if we've mixed our audio with a broad range of volume levels (which he calls a very "dynamic mix"). "Trying to listen to a very dynamic mix on smaller systems will always result in your content sounding weak," he observes. "Although the content sounded great in the studio, where we had a low noise floor and we could turn it up, in a crowded office the quiet details were just almost always inaudible. However, if you go too far the other way, having no dynamic range is just really boring."

Taylor warns us that when we're mixing our work with very high-end equipment and monitors such as a surround system (pictured left), we may end up with mixes that sound significantly sub-par when they're fed through lower-grade speakers. This effect may be especially pronounced if we've mixed our audio with a broad range of volume levels (which he calls a very "dynamic mix"). "Trying to listen to a very dynamic mix on smaller systems will always result in your content sounding weak," he observes. "Although the content sounded great in the studio, where we had a low noise floor and we could turn it up, in a crowded office the quiet details were just almost always inaudible. However, if you go too far the other way, having no dynamic range is just really boring."

So, what is the solution to this problem? Taylor suggests that we opt to reward listeners who have invested in high-end sound systems. "Always mix for the best case scenario," he advises. "If your game requires or suits having a large dynamic range, always mix for the large dynamic range and then use the mastering processor to compress down to suit smaller systems." He adds this warning: "It's easy to reduce dynamic range but it's not easy to increase it."

As a side note, I'd like to mention an interesting concern that is suggested by Taylor's discussion of mixing and mastering tools that are built into a game's audio engine. Usually, when delivering linear music for use in any entertainment project, we can be confident in our mix and master because we have recorded and delivered it in its final, stereo format. But when introducing musical interactivity into the process, things become much more complicated.

In my book, A Composer's Guide to Game Music, I discuss an interactive music construct known as Vertical Layering. We've explored this technique in greater detail in my blog before, but I'd like to come back to it now because this type of music has the potential to be directly impacted by the in-game mix and master process that Taylor describes. When delivering music in Vertical Layers, we as game composers are essentially separating the musical elements and affixing them in discrete recordings meant to play in a synchronous, simultaneous fashion. In this case, the game engine itself becomes responsible for the final mix and master of these independent musical "layers."

In my book, A Composer's Guide to Game Music, I discuss an interactive music construct known as Vertical Layering. We've explored this technique in greater detail in my blog before, but I'd like to come back to it now because this type of music has the potential to be directly impacted by the in-game mix and master process that Taylor describes. When delivering music in Vertical Layers, we as game composers are essentially separating the musical elements and affixing them in discrete recordings meant to play in a synchronous, simultaneous fashion. In this case, the game engine itself becomes responsible for the final mix and master of these independent musical "layers."

As games more frequently employ interactive music constructs such as Vertical Layering, we may find ourselves becoming more interested in how the overall signal processing capabilities of the game's audio engine are impacting the final mix of our interactive music recordings. Achieving a stellar final mix is challenging in the best of circumstances. Working together with audio directors and sound designers, we game composers will have to be especially vigilant, knowing that the mix of our interactive music isn't truly "final" until the game is being played.

Garry Taylor's talk at GDC 2016 is very detailed and includes a live demonstration of the Sulpha software application - those with access to the GDC Vault can watch the entire video here.

I hope this blog was able to convey some useful music and audio production tips from two GDC 2016 sessions. Thanks for reading, and please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section below!

Winifred Phillips is an award-winning video game music composer. Her credits include five of the most famous and popular franchises in video gaming: Assassin’s Creed, LittleBigPlanet, Total War, God of War, and The Sims. She is the author of the award-winning bestseller A COMPOSER'S GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC, published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. Follow her on Twitter @winphillips.

Winifred Phillips is an award-winning video game music composer. Her credits include five of the most famous and popular franchises in video gaming: Assassin’s Creed, LittleBigPlanet, Total War, God of War, and The Sims. She is the author of the award-winning bestseller A COMPOSER'S GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC, published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. Follow her on Twitter @winphillips.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like