Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Foundation 9 (Death Jr.) is likely the biggest developer conglomerate in the world, with more than 800 employees - so how is it doing in 2008, and what on earth is its 'Total Quality Initiative'? Gamasutra finds out...

At the DICE Summit in February, Gamasutra got the chance to sit down with Jon Goldman, exec at Foundation 9 (Death Jr.), one of the (and possibly the) largest independent development company conglomerate in the world.

Spread across North America and Europe, the company has no publishing elements, and includes studios as diverse as the U.K.'s Sumo Digital, U.S.' Shiny and The Collective, and the U.S. and Canada's Backbone Entertainment, among others, with more than 800 employees spread among multiple major offices. Its games include Sonic Rivals, Monster Lab, Godzilla: Save The Earth, and a host of remake and 'classic' titles.

Here, Goldman discusses his company's Total Quality Initiative, which seeks to increase the studios' game quality, the nature of pairing up development opportunities with the right studios, and how their studio management philosophy is similar to EA's new city-state ideals -- before EA even announced them.

The first thing I'm curious to talk about is the Total Quality Initiative that was recently announced. If you can give a little bit of background on that first...

Jon Goldman: Sure. Last year and this year, we started tracking quality numbers, and we saw that... last year, we issued a press release where we moved up in average quality by about two or three points, while the industry average actually went down. And that's actually not uncommon, and that's part of the cycle. In the early part of the cycle, quality averages go down.

But we were surprised that our quality averages have actually gone up, because people associate work-for-hire licensed development with quality issues. We realized that one, there's a perception gap, and two, this is something we can manage to do and continue to improve. One is selling point, and two is a recruiting point. So, selling point for publishers, and two is a recruiting point for telling people this is a quality place to work.

The other thing we faced is that we really grew a lot over 2007. As a management team, we can't know what's going on with 60 projects, because that's what we had going on last year.

We have to have some process in place that shows that we're actually exercising oversight, because there are a lot of points where we looked a publisher in the eye and said, "I'm committing to this," and I certainly don't feel comfortable as a CEO looking somebody in the eye and committing to something with which I don't have any oversight function, other than turning it in.

So there's that, and there's also just really making sure that our employees and other folks know that as we grow, we take this seriously. That's an important motivating message to people, that big companies, not just small ones, can care about the product.

Because a lot of what I, or other people, message is about profitability and performance and things like that. But everybody knows that there's a difference between doing good product and doing good business. We want to make sure that's institutionalized, and not just something that we talk about.

Taking a step back, what does "quality" mean in this context, and how do you assess it?

JG: There are a few things. We're really looking at like quality, so for particular games, like a little kids' Hamtaro game, we're comparing that to like games.

For Silent Hill, we're comparing that to like games, given whatever parameters there are. There's quality metrics that come in from the reviewer press, there's which games sell really well, we look at that metric, and then we look at other things like the budget and timeframe and those things.

So when you've got a basket of 60 projects, you can actually do some true comparisons. So we can't compare a $15 million project to a $30 million project, but we can compare a couple of $15 million projects with similar timeframes with each other and say, "Look, this is where we should've done something differently.

We should've changed the scope in this way, and we should've done this feature better." Those things. We try to get very analytical about it.

Is quality of life part of that too, for developers?

JG: No, it's not [part of] Total Quality management. That is part of our HR function. As most people who know me know, I used to be a fairly sarcastic guy, but I've come on board with a large organization, and we've got some core values, and our top core value is taking care of people. For us, that means employees, shareholders, publishers, and everybody we're dealing with. So quality of life for employees is important.

To tie it together, one of the things that's important to our employees is success. They want to know that they're working on something that they're going to feel good about in the end. For a lot of them, they're getting to a place where they have kids and other things going on, and they want to know that they've got a reasonable career, and not just a fire drill.

You have a lot of studios in geographically diverse locations. Does managing that, or maintaining that base present a challenge?

JG: That's what I've done my entire career, and I think a lot of our key leaders have as well. So I think challenging, yes, but it's a competitive advantage, because we've had to figure out how to do that for well over a decade.

Super Street Fighter II Turbo HD Remix is among the most anticipated titles for Xbox Live Arcade

Some of your developers are known for their Xbox Live Arcade projects, whether it's classic games, or obviously Street Fighter is a big example of a highly anticipated download game that one of your studios is working on. But there's a little bit of a fear coming right now, where people feel like it's less possible to have a standout hit in Xbox Live Arcade the way you could a year ago, because there's more on the market. Do you guys perceive it that way?

JG: The way I look at it that gets me excited is that... I can't remember what the last figures are, but by the end of this year, there's 18 million units out there, of which I don't know how many will be Xbox Live Arcade-ready. So maybe it will be a standout hit.

We'll hit harder because it will be more noise, but I think to reach a level where a game can be successful, both in terms of reaching a big audience and making money will be more and more achievable as people buy these consoles.

Now, the PlayStation Network is still a little bit nascent. But it's viable, too, and Street Fighter is going to both networks. How do you view the rise of that as well?

JG: It's great. From our standpoint, we don't like to pick horses, and the more viable platforms there are, that plays into our business. Remember, we're a broad-based developer that does everything from handheld to next-gen.

We still do last-gen stuff, PC stuff, little kids' stuff, and mature stuff. So that's something we welcome, particularly with the changing revenue model with Xbox. It's exciting for us when there's a viable PSN or a viable WiiWare. We like that.

Something you said a minute ago -- you guys do a lot of work for hire, or you take on external projects for publishers; later you talked about how you do a variety of projects. Some are big, some are small, some are kids, and some are core gamer. Are your studios formulated that they have core competencies, and the studio will get projects of similar scope and platforms, and other things?

JG: Absolutely. Our studio in Boston, for example, is the place where we do an entertainment title, a value title... those two things. They would not work on a mature, core title. Of course, talented teams evolve over time, but we don't just shove things willy-nilly. It's very important as well to understand that we don't shove anything anywhere.

The studios have to accept something, so the corporate side of things can queue up opportunities. We can help them close opportunities, but the studio has to grab it and say, "I want to work on this." The team has to be interested in it.

Interestingly, what John Riccitiello talked about today has been our philosophy from the beginning. I think it's telling that it takes a long time for a big publisher to figure that out, but we were all developers ourselves, so as we acquired studios, we knew that intuitively that what studios want is autonomy, voice, and in many cases, may need help running business, giving me a chart, running finance, and doing those sorts of things.

But why would we buy them to change them? The reason we would buy somebody is because there's something there that we like, and that just seems very self-evident to me.

Well, some acquisitions that you've made are kind of special. A lot of people feel strongly about Sumo Digital, because of their work with Sega and the great job they've done revitalizing that classic Sega feel... they've kind of done Sega's job for them, in a certain sense, keeping the spirit alive. There's an interesting mix of studios.

JG: There definitely is. If you're saying gingerly that some studios are very self-sufficient, that's true. Some studios may need help in different areas. One of the goals is to help them, but not to force them to do something. For example, if there was a prospective team where we thought, "Well, this is just so broken that we'd really have to fix everything," we'd probably steer clear of that.

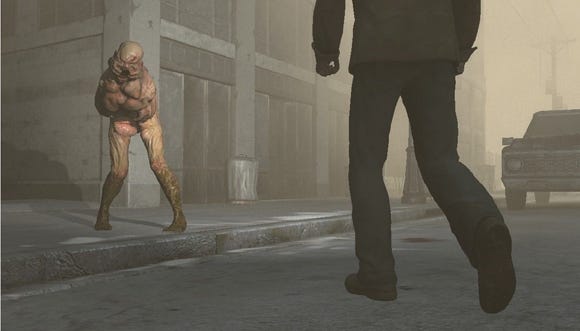

Konami's upcoming Silent Hill V

You'll have to forgive me if I misspeak myself here, but I would say that Foundation 9 has up to now been known, or more famous with gamers, with some of the online game work, as well as games like Death Jr. But it hasn't been known for big, ambitious games like Silent Hill V. Do you think that's changing? Is that something that you're moving into more?

JG: Well, we've got a few big-name game projects in-house, so this isn't a day-and-date, but it is a big project. I think that it's easier for us to do that now, because we've been able to consolidate some technology and put together bigger teams and some oversight processes like the quality initiative, and some other things going on that allow us to reliably deliver on those kinds of projects. And Silent Hill V [in development at F9-owned studio The Collective] looks great. The team down there is really making a beautiful product, and it sounds nice and spooky and it's eerie-looking.

So I guess to get to your original question, there will be some of that, but we don't have any self-loathing about some of the other projects we've worked on as well. One of the keys to Foundation 9 is a portfolio. We've got a portfolio of projects from big to little.

Some would be sexy to core gamers, and some wouldn't, but some are really exciting to mass-market players, and some aren't. That's kind of our ethos. Where people are playing, we'd like to be active, and we've got enough studios and talent with interest in those different areas to make games for them.

One thing that John Riccitiello was saying this morning was that ten years ago, you really only had to ship games on three platforms: the PS1, the N64, and the PC. Now they ship on 12, plus mobile. How are you guys struggling with it? Or rather, I don't want to put words in your mouth -- I'm not saying you're struggling with it.

JG: We're not. We haven't done mobile in a while, because as the budgets on even the smallest platforms grew, doing a couple hundred thousand mobile deal just didn't make sense. But on every other platform, we're not struggling at all, and as I mentioned, that's one of the core strategies, is through size, being able to handle that in a way that we couldn't do when we were all smaller.

It's important for people to remember that, again, we were all developers. This isn't some financial scheme that guys who were in the video game industry pulled together and started roping in some developers. These are people who were developers who realized that yeah, through size and scale, there's strength, security, and ability to invest in the future.

As that plays out on all these platforms, it means that we've got great DS technology, great PSP technology, and a couple of different great next-gen engines. We've got good rendering and good toolsets that we can bring to bear games that people are playing.

As long as there are enough units out there... there are tons of DSes out there, right? Okay. We're happy that market exists, and it looks like there's a little uptake in PSP. That's great, and we're happy about that. That's all good, from our standpoint.

You were just talking about how you have some great technology solutions. Do you have a core tech group, and then ship the solutions out to the studios as you complete them?

JG: That's an important concept, and I think it's also something that was referenced in the talk earlier. From the beginning we talked about -- and I definitely talked about -- being demand-driven on technology. We all lived through the whole RenderWare experience. So being demand-driven, as opposed to supply-forced.

We knew, because we worked around everybody, that there's no forcing somebody to use something. The best thing you can do is get people meeting together and say, "Hey, here's some code. Want to take a look at it?"

If you say, "I'm making you take a look at it," then they might not take a look at it, but if you put something up on the server and say, "You think you might be interested in that?" then I guarantee you that people are going to look at it, and they start talking, and a little bit of sharing happens. We've had some success there. Some teams don't want to share with each other, because it's just not efficient for them, and we don't enforce that.

But as a business, we set financial goals and boundaries, and people like smart guys, and video game developers are basically really smart people, despite what people outside the industry might think. They respond to this sort of stuff.

If it's more efficient for them and they can make more money and their life is easier because they can adopt something, then they will. If it's harder but they just want to do it because that's how they want to do it, and it's going to make the product and get it done on time, that's fine too. We're not forcing people to do stuff.

It seems to me that in discussion with developers, there's sort of a fine line at which they're enthusiastic about the option to adopt technologies, but dislike being asked or told to adopt technologies.

JG: I think nobody... well, one way of perceiving that is stubbornness. Another way, if you've actually been through production, is to realize that you're under the gun all the time. You've got to figure out your core technology and develop a game all at the same time. In a lot of industries, they've got an R&D effort, and then they figure out their widget, and then they stamp out a bunch of those widgets.

We're always doing R&D and making the game at the same time, so there's a huge benefit and risk negation from using what's familiar. You know what's wrong with it, and you know what's good about it. That creates a big barrier for adopting something else.

At the end of the day, our goal is to get the right game done, and get it to the publisher. We don't want our publishers to be biting their fingernails and staying up at night. Sometimes, you go for what's sufficient and what's good, instead of what's optimal.

Yeah. It's interesting, too. Here's an example. I was talking to people from BioWare and Pandemic, and when they merged originally, pre-EA, they started looking at Mass Effect and some of the projects that were in development at that time, and realizing what they could share. That actually touched off inspiration creatively, too.

JG: I think if you set the right atmosphere, it makes it feel good and fun for it to happen. That's probably the way it is in a lot of creative pursuits. People need to feel like it's fun to collaborate, as opposed to, "This is part of somebody's corporate plan of how to wring every ounce of efficiency out of..." You know.

Well, games are so intensely collaborative -- indies aside -- it's absolutely essentially impossible to make something with even a few people, at this point. So people who work in games have to get in the spirit of that. It's kind of what Gore Verbinski was talking about in his keynote -- he has the freedom to pick and choose who he works with, because of his stature. But I've noticed people very much do gravitate together in this industry. They stick together when they can.

JG: I agree.

Is that how you find the studios you end up either acquiring or working with? Is it about the creative people, or is it about filling a niche in your business?

JG: I'm a biz guy. I don't make any bones about that. I look at the strategic stuff, but then after that, that's what gets you to talk to somebody and you get to know them, and you see if there's a fit. Almost everybody in one way or another fits in our company.

We've been doing it for a long time, so it's not like somebody who's woken up and decided they wanted to make video games. We've experienced the ups and downs together, so we've got a longer view of it. So personal fit is incredibly important.

Another thing John Riccitiello brought up is that EA used to shop its culture into their studios, and now the culture is seeping into EA from the studios. Do you feel like it's similar at F9?

JG: Well, I think we're a different situation, because they're a publisher who's acquiring developers, and there are actually a lot of different cultural issues. If you look at it as a publisher, development is a cost of goods, as opposed to a source of revenue. It's all we do. Development is our business. It's not something that serves what our real business is, which is...

Shipping SKUs to Wal-Mart.

JG: Right. That's a natural potential friction there. The good parts of being a developer in a publisher is that there's probably a little more leeway in terms of some of the constraints you have, and you're part of a company that's capturing all of the upside, and there's some great franchises there. That's not a bad situation, but our deal is that we all come from the same background to begin with, so I think there's isn't that...

Push-and-pull, kind of?

JG: Yeah. I mean, the only push-and-pull is the natural push-and-pull is trying to have a creative endeavor inside capitalism to begin with, which is hard.

You guys aren't a publisher, and you do a lot of Xbox Live Arcade and PSN games, but you have them doing them for publishers. But you could cut out the middleman if you wanted to, right? You could go straight to Xbox Live Arcade with your own game. Have you considered doing that?

JG: Yeah. We're formulating various plans around that, but it's not an either/or situation. If somebody has a great property like Street Fighter or Bomberman, that's their property, so the only way that we can work on that is if we work with them. And XBLA and PSN are great opportunities for us to spend some of our money too.

Are you guys working on your own original IPs? Silent Hill V is a big, ambitious project, but ultimately, it's Konami who's in control of the Silent Hill franchise. Climax made the PSP one probably in hope that they'd make the console one. I'm totally theorizing, but you know what I'm saying.

JG: I do know what you're saying, but... we have had some traction on projects like Death Jr., and we've got another one - Monster Lab - up in our Vancouver studio. That's part of the plan. We define our business as a portfolio, so the bulk of what we do is the kind of business we do right now.

We like the touch and feel of Silent Hill, and I think it's important to point out that there are a lot of people who are doing the types of titles we are doing that have a little bit of self-loathing. They hate what they did, because they really wanted to do something else. Silent Hill is a great project, and a lot of projects...

I think that would be exciting to work on, personally.

JG: Yeah. That's a good thing. And then there are some things that you vest in your own account, and if we do it all right, there will be a portfolio of things that are stuff for publishers, stuff that's our own stuff.

Naming no names, I do know people who work at studios that work on licensed products, and they have a continual dissatisfaction with the fact that they aren't able to do what they want, or what they got in the industry to do.

JG: I can empathize with that. Again, I think it's hard, as a general statement, to get everything you want in a commercially creative endeavor. That's the difference between commercial arts and fine arts. You can be a starving painter and show your work in galleries, and maybe you'll hit it big, and in the same way, in our business, you make sure you work on skills to make games, and sometimes you get lucky and you get to push an original thing out the door, too.

I want to make clear that it's not our strategy to keep people from the work that they find exciting, but we operate in an ecosystem that is defined by making money, so we figure out how to balance selling those opportunities. That's what we have to do. From my standpoint, I'm just as happy to sell any type of deal, because we never force a deal into the studios. If they've got a deal that we can sell that's their own special thing, and we've done that twice in the past couple of years, I'm excited to do that.

Something that Verbinski said that really struck me is that when he was working on Pirates of the Caribbean, he went into a merchandising meeting with Disney and they showed him, "Here's the posters, here's the Jack Sparrow dolls, here's the game." And he's like, "Why is the game equivalent in your eyes to the posters? How is it merchandising? Why isn't it on the level of the movie, as it should be?" Do you think maybe some of the licensers maybe don't give the games their due? It's on them too, that these things don't reach full flower.

JG: There are actually structural explanations for this. Over time, they will change, as younger people come into positions at those companies. But structurally, video games are often situated under consumer licensing in big media companies.

These are the same groups who are licensing pictures on Underoos and bath towels and what have you. That probably made sense for a long period of time, particularly when the video game industry was a lot smaller than it is now. It was just another revenue stream.

I think what we've seen over the past decade in particular is a shift in demographic behavior where kids are spending more time in this medium. So yes, it means that this medium is just as important, or even moreso, to brand as the movie.

You spend a couple of hours in a movie, and if it's a really good movie, you're satisfied. But if you spend four, 10, or 20 hours in a game and it's not so good? That could devalue that entire edifice.

So yeah, I think people will get around to figuring out, sooner or later at the very least, that the brand-holders will spend a little more up-front time figuring out. And hey, Gore Verbinski is the creative force behind that, so pointing the finger at Disney and saying, "Hey, how come you guys aren't thinking about that?" I think that's kind of where it has to originate -- "Hey, I'm the creator of this brand. Why wasn't I thinking about the game?"

The last thing I want to point out is that I want to see more licensed games that are better than their licensed source. The classic examples I'm thinking of are King Kong by Ubisoft, I think was better than the movie...

JG: Chronicles of Riddick is a classic example.

And Chronicles of Riddick, there you go. That's the other one. That's what I want to see more of.

JG: You know what I say to that? More time for development. It's a huge problem. We do a lot of day-and-date movies, and a huge challenge for day-and-date movies is that by the time it gets to us, we have 12 or 13 months, or maybe 16 months. Games take more time than movies.

Movies take a long time to gestate in the script form, but they actually go pretty rapidly from greenlight to production to day-and-date release. We need more time in games to really tune and polish things in a way that I think linear media just doesn't.

Chronicles of Riddick, an example of a game that's better than its licensed source

Do you think that because of that structure of process in Hollywood makes it impractical to properly incorporate game development? Because you don't want to give someone a contract to make a game for a movie that is probably going to get made, but hasn't been greenlighted fully yet.

JG: You know what? I bet you could invest... let's use a guy like Gore Verbinski as an example, because he's somebody who, as you say, can pretty much write his own ticket, right?

So if I could pull all the puppet strings, I'd get preproduction running on the game and the movie at the same time, even before it's fully greenlit, because for not too horrible a cost, you can get a lot of design work done, and hey, they're paying those movie guys a ton of money, so they obviously have a lot of money to spend, and you could come out with a much better integrated product. If it doesn't get greenlit, well, there's some costs in the movie industry.

I've heard from developers also that one thing that would help game development is more time for brainstorming and prototyping at the front end, anyway. If you could align those two, that actually would be really beneficial.

JG: And we're also -- and this is another good thing to talk to Rich Hare about -- is really understanding the type of scope you can have for the amount of time that you have. A lot of times, we find ourselves getting excited about something, and you have more scope than you have time to do, given the short cycle. You're always looking back, saying, "Hey, ifI'd spent more time polishing and fine-tuning, and less time just adding my favorite feature..."

You know, you see that so much in games. You see it so many times and you're like, "I see an idea here. I do not see an execution of the idea."

JG: I'd much rather get a review that says, "Hey, really cool, but not enough of it," than "Well, this stew has so many vegetables I don't know what the hell to name this."

This is personal taste, but I really like reductive games, games that take very few things and then keep surprising you with how they use them again and again.

JG: Just get something right. Leave somebody wanting more.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like