Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Ninja Theory co-founder Tameem Antoniades on balancing story and gameplay while working with a Hollywood scriptwriter, and how the idea that a game must have one unique selling point is an illusion.

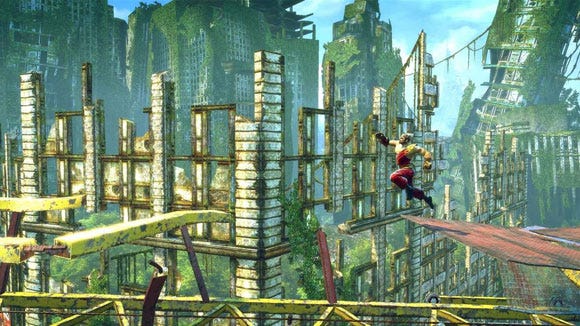

Cambridge studio Ninja Theory made a splash early on in the PlayStation 3's lifespan with Heavenly Sword, a game published by Sony that blended melee combat and surprisingly deep characterization.

With its next game -- the first since that title -- the studio co-founder and chief designer Tameem Antoniades hopes to amp up the drama, which he sees as integral to the game as its core gameplay. To this end, he's brought in Alex Garland, writer of the tense zombie flick 28 Days Later.

Here Antoniades discusses the process integrating the writer with the game team, as well as how to strike the correct gameplay between balance and story, adapting the Chinese Journey to the West myth into a contemporary game story for a Western audience, and how the current generation, emerging technology, and the state of the independent studio landscape is affecting game development.

What was the creative process for this IP? Obviously, it's based on the Monkey King stories that have inspired a lot of media, but how did you arrive at this?

Tameem Antoniades: It's partly the relationship we set up between Nariko and Kai in Heavenly Sword. I read the forums, and a lot of players really responded to that. They really care about this secondary character, which was great.

One of my favorite games of old was on the Amiga, Another World, also known as Out of this World, yeah. In fact, I spoke briefly to Fumito Ueda once during a conference, and he said it was that game that inspired him to make Ico.

And so I actually quite like the idea of having a secondary character and to see how it would affect gameplay and story. I see those as equals, story and gameplay. They're both as important as each other. They both support each other.

Relationships between characters can really bring games to life, in a way. Just one solo person going through an adventure, it can feel very canned. It doesn't have a sense of realism.

TA: Yes. And I think that's partly why in movies you have all these secondary actors to play off. Otherwise you've just got this lone guy, and the only way he can really tell you what he's thinking is by actually saying it. That's not believable for a guy to run around just talking.

So, yeah, I think dramatically it's really important to have that secondary character, especially like a game Enslaved where the Monkey character, he's actually a loner. He doesn't like people. He doesn't speak much, so he needs someone to kind of bring it out of him.

Did you look at any of the other adaptations? There's everything from Dragon Ball to what Damon Albarn did. There's a huge variety of adaptations for this material. Did you look at any, or did you just go straight from the legend?

TA: I read the original book, and there's this one particular version, the Arthur Waley version. That's the one that's actually considered the best. I was just blown away by how cool it was, like so much imagination -- a 400 year-old book, and so rich.

In the UK, there was a TV series of Monkey, a Japanese TV series that was aired. Everyone over 30, say, remembers this show, and there's a real cult following behind it. In fact, we had the monkey character in our first game, Kung Fu Chaos, as one of the characters. [laughs]

And I did go to see the Damon Albarn show as well, which I thought was just phenomenal, really phenomenal. It's interesting that when it gets adapted; it never gets adapted closely to the source, so I wasn't that concerned with staying true to the source. It's more loosely based on it.

It's interesting because very often with Western developers, people concentrate on Western myths, not Eastern myths, so it does add a difference. Do you find that that allowed you to be freer because people aren't maybe as familiar with the source material?

TA: Yeah. Basically, it seems like we're treading old ground. I'm talking collectively we as an industry. A lot of our games are based on the same mythos and influences that we grew up with -- Blade Runner, Aliens, Lord of the Rings. You can pretty much count them on a hand, and that will cover about 80 percent of games out there.

I do like Eastern cinema, Eastern movies, because they've just got a totally different perspective on it, which I find refreshing. I would never have read Journey to the West if it wasn't for the fact that we were doing Heavenly Sword and I was doing research and finding out about the mythical Chinese world. Yeah, I loved the fresh perspective.

How did you come to work with the screenwriter Alex Garland on this project?

TA: Yeah. So, he did 28 Days Later and The Beach and Sunshine. And he's a producer as well, on those movies. This is actually the first contract job he's ever taken. Everything else he's ever written he's done off his own back, and they're his own stories.

It turns out he's a massive gamer, and he's on Xbox Live all the time and he's got his own clan of friends -- they don't know who he is. And so he wanted to get involved, and we just gave him full access. He's been brilliant.

A lot of developers talk about how people who come from movie backgrounds sometimes have difficulty integrating. They're used to handing in drafts, and games actually change a great deal as they're developed. Have you found that it's been easier to integrate him into the team because he understands the medium?

TA: I think that had a big hand in it. I really do. The other thing that we were very clear from the beginning is that if you want to make a successful story in the game, then you should try and tell as much of the story as possible in gameplay.

So, you can't write in a vacuum. So we co-wrote it basically -- him and us. He'd come up every week for a full day, sit down with our level designers, with all of our designers, and then we'd map out the levels and how the story beats go on in the levels. So effectively, he's got a design credit in the game because he contributed so much to the actual design.

How do you organize that process of building the levels out and integrating the story in a game where you want to tightly integrate them?

TA: The approach we took is to write it as if it was an action movie and not get too concerned about which parts are cutscene versus gameplay. Basically, the story by itself should work, and then our job is to figure out how we integrate that either into the gameplay or into a cutscene. I think that's the simplest method that we came up with.

How did you make the determination? Was it based around pacing of the story, or was it based around pacing of the gameplay? What seemed appropriate?

TA: I guessed that if it feels right on the page, it will probably feel right in the game. So, my advice to Alex was, "Write it how you would write a movie. Don't worry too much about what the gameplay implications are. Just write it like you would a movie. If it feels right, if the drama, the beats, and the action feels right, and if it's paced correctly, we can find ways to kind of build around that."

So, that's how we actually integrate talent from outside. We tell them, "Don't worry about the game side. We're here for your skills. Don't try to change what you do for us. Let's just work together really collaboratively. Don't be afraid to voice your opinion. Don't be embarrassed. Just make everyone feel really safe and comfortable."

The complication is that movies are much shorter, and the actual balance in them tends to be quite different. We all think of action movies as being very high action, but if you analyze action movies, they actually have a low number of action sequences that punctuate the drama, so that's the reverse of games -- it's more drama punctuating action.

TA: No, that's true. That's very true. But again, like when you're playing a great story-driven game... One of my favorite games of recent times is Uncharted 2. When I'm playing through it... When I come out of it, I think of it like I would do a movie. It's got a very clear act one, act two, and act three. It doesn't feel overly convoluted, long...

It doesn't feel like a TV series where stuff's happening all the time. So, again, my advice to Alex was, you know... He's asking, "How long should the script be?" And they were kind of minute per page, and I said, "The length of a good, satisfying action movie." So, you know, whatever.

90 pages, 90 minutes.

TA: 90, 100. That kind of range. And that seemed to be okay. That seemed to work.

Obviously, there's a lot of debate over how story integrates with games or how relevant it is. You seem to feel pretty strongly that it's an equal partner.

TA: Yes. I definitely would. I would rephrase it as, "What we are creating is a story adventure." Every element of the game should support that. So, I actually see story as -- and I'm not embarrassed to say it -- the most important part of the game experience.

And everything, including the gameplay, which has to be solid -- the sounds, the cinematics, the cameras, and the action -- all of those things are part of the story. And if you manage to integrate all of those layers together, you get this kind of transcendental experiences that you remember from gaming yore that you get in games like Ico, Out of this World, the games that you hold dear to your heart and that you never forget.

They're the ones that have managed to just transcend above the sum of their parts. That's our ambition. It's difficult. We don't know if we'll actually achieve it, but that's what we want to do.

Aside from storytelling, you guys have had a real focus on melee combat. Obviously, you have Heavenly Sword, and this has a melee combat focus -- and Kung Fu Chaos, for that matter.

TA: Yeah, yeah. I guess it started from Kung Fu Chaos, and since we've always been building on top of our last game, it's carried on. It's different in this game. It's about a third of the experience in this game. It's actually really, really tough to actually carry a whole game with one mechanic, which is combat. In Enslaved, we focused on areas that we didn't tackle before -- puzzle solving, traversal, that kind of thing.

It seems that we sort of as an industry fall back on combat because it's something that we understand how to do, and it's something that is rewarding and engaging. How do you strike the balance that you want to strike this time out?

TA: Yeah, I don't know. When you walking on a trade show floor, you see just so much -- this barrage of action, violence, shooting, fighting, and swordplay. Fundamentally, it's familiar. We know we can make fun, melee combat, which is why we all do so.

But one thing, I think, that's starting to shift, is the idea that a game has to have one selling point. You go to a publisher and you pitch an idea, and they'll ask, "What's your main selling point?"

When I look at some of my favorite games, I can't spot my main selling point. When I look at Uncharted 2 -- I keep referring to it because it's fresh in my memory -- I can't spot a single selling point. The selling point is it's by Naughty Dog, it's got a great story and a great game, and everything works really good.

And I hope that trend continues because I think we've got to move away from the gimmicks of gameplay and more into the overall experience.

Mechanics versus experience -- it's different ways of looking at what games can actually deliver.

TA: Yeah. Yeah.

But at the same time, to have elements in a game, you do have to nail them from a technical and from the feel. If the feel isn't there, it's not going to fly. So, you have to put that work into those.

TA: Yes, yes. Absolutely. And when I keep talking about the story and the experience, I see very much gameplay mechanics, sound, music -- all those elements have to be rock solid because they are part of it. You don't have to compromise one for the other.

When it comes to actually developing the solid gameplay mechanics that underpin the experience, did you spend a lot of time prototyping out the interactions before you launched the production of the actual game?

TA: Yeah, so we probably spent a year and a half in pre-production, which I think should be about standard. I think you should probably be spending at the very least about a third of your development time, if not more -- half, ideally, actually -- in pre-production.

Was that primarily focused around prototypes of gameplay?

TA: Yeah, so one of the ways we approach mechanics is we prototype and iterate the mechanics as much as possible, and then we test it. So, before we put them into a level, we create gray box scenarios just totally out of context so that designers don't have to worry about "How does this fit into the story or the world?" They're just stress testing each mechanic in different gray box rooms. And then once we know which bits work really well, we can then integrate them into puzzles and the gameplay. I think that approach worked very well.

Did you get as much out of it as you were expecting? Did you spend as much time on it as you expected?

TA: Well, I mean, when we moved from Heavenly Sword to a multiplatform title, we had to basically start from scratch because all our tools -- engine and everything -- is owned by Sony.

So, we chose Unreal. It actually allowed the designers to start working immediately. A lot of our designers have programming backgrounds, so they can start prototyping without any help at all, and that was brilliant.

It's interesting to see that you chose Unreal for like this sort of sprawling action-adventure game. How did it work for that?

TA: By the time we had decided to use Unreal, there were already PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 games out using it, so we avoided the growing pains, if you like, of early titles on Unreal. The toolset's really mature, the engine's good. What we did do is look at the Unreal games, the really good ones, and say, "Okay, this is the kind of game it can do really well, so let's design our game around that. Don't go against the grain."

It's hard to think of an action-adventure game that used Unreal really effectively.

TA: Well, we were more looking at level structure, so things like BioShock and, you know, Gears.

And for a small -- well, we're about a hundred people now -- but for a fairly small-ish, I guess medium-sized, independent, you want to use the talent you've got in-house to craft an experience as much as possible unless your technology development people have already done several times over.

What do you think of the UK development scene right now in terms of its vibrancy and its talent?

TA: I think it's a bit tough actually. Like the UK has always punched above its weight, I believe, in gaming. And tax breaks are available in Canada and so, and that's hurt. The UK has dropped ranking in terms of from third to fourth, soon to be fifth. A lot of developers have gone bust or they've been bought out. There's not a lot of independents that can do triple A type games left. So, it's slightly scary but also exciting.

Do you guys have two teams up and running? Do you have two projects?

TA: Yes.

That must have been an exciting moment when you realized you were at that point. Because you previously have done one game at a time.

TA: Yeah. We were warned about expanding to two teams. It's kind of the make-or-break for a lot of companies, and we did it very slowly. We were hiring one or two people a month. We were seeding the second team with the leads of the other team, promoting people to fill their place, and hiring people under them. So, it was always extremely considered, slow, and gentle, and it's paying off doing it that way.

When you say there aren't that many independent teams that can do triple-A games in the UK, I think that's actually generally true. There aren't really as many independents these days that can do that. A lot of them get snapped up by publishers.

TA: Yeah. I think you're right. But I think if you are independent, I'm noticing that you're getting a lot more attention from publishers. More opportunities come up that you wouldn't have considered before because publishers need games. They have to be growing, and they have to be selling games, and they need people to make those games, so the desire is there. It's just a business model that's incredibly tough.

Games cost a lot to develop, and that creates a lot of difficulties in selling them. There are a lot of really strongly competitive titles in any given genre at any given time.

TA: Yeah, but at the same time, there's totally new emerging platforms online, free-to-play models, and all of these things on the horizon. I think online gaming ultimately is a win win for everyone, so it's going to happen. It's just a matter of when.

You're talking about how publishers have a lot of interest in working with independent developers, and you also talked about a need to move forward with games that have just a single selling point, that have more of an experience. Do you find that having those conversations can actually be a bit tough? Or are publishers generally receptive?

TA: I think it's still tough. People still want to know what "the X" is, so thank you very much, EA. Every single game, I struggle with that concept. How do you reduce everything that makes up some of these amazing games to one line, and then focusing on that one thing like a mantra doggedly at the expense of other aspects of the game? Something just doesn't sit right with me and that concept of the X.

But it's still forced on us. [laughs]

Have you looked at some of the independents that, you know, can kind of write their own ticket now, like Epic? Do you think that there's a way to get to that level, you know, for other independent studios?

TA: Yeah, yeah. Also, those guys make a lot of their money off their tool side, the engine that they sell, and that's given them a huge advantage. They can make their games the way they want to do it, and they can do it on their own terms, which ultimately, I think, is how it's going to be.

I think we're still going through that shift. I would love for us to be in that position, too. We're going off the back of our experiences, and people respect us for that, but if you don't have those hit titles behind you, it's really, yes, it's a wonder to me how there are even so many developers out there that survived.

Well, it's difficult because typically people have been operating from milestone to milestone, and you need to sign something before the prior project ends, or your payments are going to dry out and you can't make payroll. That's not a stable model to operate under.

TA: No. No, it's not. And I would like for us to be like Pixar -- they take their time and they work on maybe two or two and a half projects on the go at once, and they craft each one, and they plan it very well. I would like for us to be in that kind of situation, so we are rolling off one team into another one.

And each one is an A-team. The B-team, I think, is so destructive to an organization, so you've got to avoid that.

The extension of this generation, as everyone speaks about. This will be The Xbox 360's fourth year, which would typically be getting on in years, but it seems like it's still quite vibrant and active, and things will persist for a while.

TA: Yeah, it seems that way. I mean, look at Red Dead Redemption. Games are still going through big evolutions. I think it's good for everyone that consoles stick around. I think there's a feeling that when the next console comes, it better be something really special because we don't want to be playing the same kinds of games over and over again. I wonder what that will be.

It also seems hard to believe that just pumping graphics power will benefit because the production costs are already so tremendously high, and art asset generation is one of the highest proportions of cost.

TA: Yeah. Perhaps I'm a little bit naive, but when we create our assets, we create them at very high res and downgrade them. So, I don't think that that's going to be the lead jump in cost. But I think the value proposition of games is getting tougher and tougher to justify.

So, games now have to have a single player, and then they have to have large components like multiplayer, co-op, DLC... There's more and more parts to a game, and games, I think, are getting bigger and bigger and more and more expensive because of that.

Do you think that, you know, all games need to have all those parts? Is it just to satisfy tick boxes? Or is it actually essential for competition in the market?

TA: I think people do expect more value for their games, but I don't think it's necessary. If you focus on crafting an amazing game... That should be every developer's primary focus because if you don't do that, you're done.

In our case, there are lots of good multiplayer games out there. People will buy our game because of its single-player experience and its story, so let's give them a full single-player experience and story. And we all have DLC, but again, it will be story-based.

I don't know the stats. I don't know if that's going to negatively impact us, but I do know that when I play Call of Duty, I actually play it for the single-player. That's just my preference. I'm paying for both. I kind of feel like I shouldn't have to. I should be able to buy the single-player, maybe pay extra for the multiplayer. Maybe our whole industry retail model is just far too rigid, and it's reaching a breaking point.

When you look at how games are getting judged, I think that we're just getting to a point in this generation where critics are also recognizing that you can't compare every game to the most expensive triple-A game.

You actually have to judge them on their own merits. Some people are getting that, and some people aren't. It's interesting to see the audience coming along, recognizing certain games for being interesting.

But when you look on the shelf and it's one box, one logo, one price -- everything in America is 60 bucks -- it's hard to make these justifications.

TA: I agree, and when microtransactions, free-to-play, and all these other kind of models that are coming out, in my opinion, the faster we go for the digital route online, the better. I think everybody making games would rather be online. Then you can have your 20 bucks for a five-hour epic adventure. You can then add extra levels and multiplayer. It's just so much more flexible. I think we are too constrained.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like