Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In 2007 Justin Hall co-founded GameLayers with an ambitious plan to bring an MMO to the Firefox toolbar, before ultimately shutting down in 2009. Gamasutra presents an exhaustive look back at the entire ride.

[In 2007 Justin Hall co-founded GameLayers, a company with an ambitious plan to transform web surfing into a massively-multiplayer online game, using a Firefox toolbar. GameLayers took on $2 million in funding and developed this toolbar game PMOG / The Nethernet, as well as two social RPG games for Facebook before ultimately shutting down in 2009. The following article, taken from Hall's website, takes a sustained look back at the entire ride, and includes links to supporting business documentation, design documents and data.]

Between 2007 and 2009 GameLayers made a multiplayer game across all the content of the internet. I was the CEO of GameLayers and one of the co-founders.

Here I'll share stories and data from this online social game startup. This story covers prototyping, fund raising, company building, strategic shifting, winding down and moving on.

In 2006, I was an MFA graduate student at the University of Southern California Film School Interactive Media Division. I was living with M (name and likeness redacted by request), a creative writing major at USC.

A reformed journalist, I attended grad school to learn to make the kinds of software I'd only written about before. I was watching people play World of Warcraft and I wanted to have those kinds of immersive persistent social travels through dataspace. WoW looked like fun!

But I couldn't focus on one MMO -- too much time investment required. How about an MMO (massively-multiplayer online game) for life on the web? M and I teased out ideas for a role playing game mapped to web surfing, so you can earn points for doing what you're already doing!

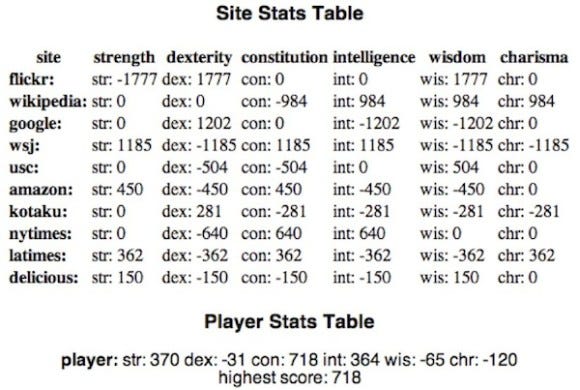

First Draft of PMOG - D&D attributes for surfing the web

Mentored by a number of agreeable engineers, I rigged up a single player prototype, using a Firefox extension that saved my web history to a file, then parsed that web traffic with PHP to give myself Dungeons & Dragons-style attributes. Surfing a lot of Flickr gave me high dexterity but lowered my constitution. Surfing the Wall Street Journal raised by intelligence but lowered my wisdom: hand-coded game values for a few sites. M made art for each of the attributes; with some art from M it was enough to present at a conference Aula summer 2006 in Helsinki, Finland.

Game maven Alice Taylor was in the audience. She and Matt Locke at the BBC had a mandate to sponsor innovative educational interactive media projects. The BBC gave us a $20k grant to build a game to teach people web literacy, on the condition we hire a British programmer.

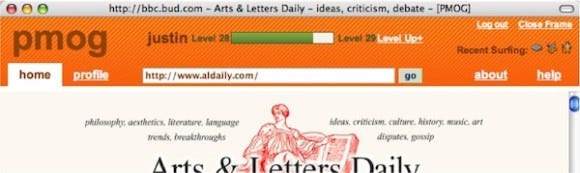

Late 2006 iFrame version of PMOG built with BBC funding

So now this became PMOG: The Passively Multiplayer Online Game. From fall 2006 to spring 2007 we worked: myself Justin Hall as producer/web monkey, game designer/writer M, and a UK game engineer Duncan Gough whom we found through our friend Matt Webb.

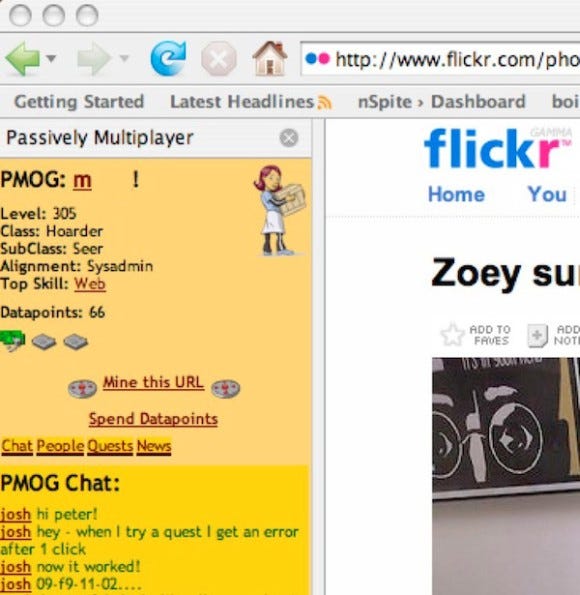

Mid-2007 Firefox sidebar version of PMOG (zoom out)

The BBC grant and the confines of Scott Fisher's Interactive Media Division (IMD) at USC provided a fine place to incubate our idea. We were supported and stimulated and challenged by smart folks with a good deadline and feedback mechanisms driving us towards a playable experience. IMD Professor Tracy Fullerton helped us run PMOG paper prototype tests; between the IMD and Alice Taylor we had good oversight to keep us focused on building a coherent experience in a finite amount of time.

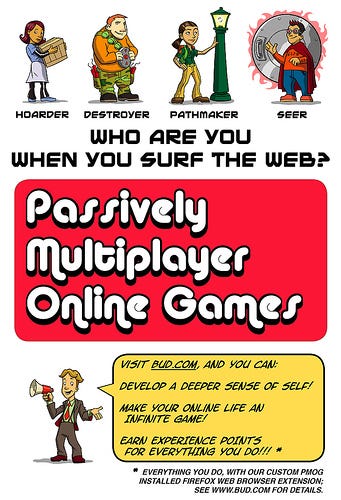

Giant poster used to promote PMOG during a poster session in the lobby of the March 2007 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco. Illustrations by the most excellent Colin Adams.

My last year there I was able to take a class "Business of Interactive Media" with a long-time game industry idol of mine, Jordan Weisman. He has started multiple successful game production companies based on new media and new markets. He shared data from his work with the class, giving me the spreadsheet tools to model the cost of running a business and launching projects. Now I could begin to imagine how to sustain and grow a new game idea.

We showed PMOG in the IMD May 2007 and we had 1,500 players! Duncan built a basic Firefox sidebar to host a working web annotation game with character records and user generated play objects across web sites, much of the functionality that we'd initially envisioned for the game. It felt like a game, or at least a fun web toy, with a chat room filling up with return players.

Here's some pictures and research documents from that early PMOG era.

As we shared our work online, people suggested we could raise some investment. We had a new type of game experience, a creative use of the Firefox platform. Maybe we were building some valuable part of the online entertainment landscape. Maybe we could be an internet startup! I had worked for some internet startups in the 1990s (HotWired, electric minds, Gamers.com), but I didn't really have a sense of how an idea turned into a business. Turns out you can raise money on an idea, and a prototype is even better!

This was mid-2007. The web was booming -- new services were being funded and taking off. There was a sense that you could grow an idea into something large, and it would make money from your large audience, or it would be acquired by Yahoo!/Microsoft/Google.

So we began presenting the game idea to venture capitalists in Silicon Valley. It was amazing to understand that this amateur game production could be seen as an economic vehicle.

Joi Ito was our first investor, an angel who agreed to come on if we could find other investors. Joi was a high velocity digital citizen and investor in a number of innovative fun projects. I had helped Joi set up his weblog when I lived in Japan in 2002, so we had some history of working online together.

Joi Ito was our first investor, an angel who agreed to come on if we could find other investors. Joi was a high velocity digital citizen and investor in a number of innovative fun projects. I had helped Joi set up his weblog when I lived in Japan in 2002, so we had some history of working online together.

In 2007 Joi was an active World of Warcraft player: he inspired us to make a game that could involve players as much as WoW involved him. Having Joi signed on first set us up to find other folks.

Joi introduced us to Richard Wolpert, another angel investor with a history of work with Disney Online, Apple, Real Networks -- AAA quality companies. He pushed us to make the experience more accessible and appealing to a broader audience.

Bryce Roberts at O'Reilly AlphaTech Ventures was interested. OATV was a relatively new seed-stage fund; they were looking for companies that might be disruptive or challenging to existing markets.

We believed we were opening the conventional massively multiplayer online game experience to broader audiences, and we appreciated OATV's roots in open source and hacker culture. Plus Bryce had great internet literacy and a fun punk-rock attitude.

I remember sitting in his beautiful conference room with a view of the San Francisco Bay, and him asking: "How much do you think GameLayers is worth?" (theoretically, after investment). I had somehow forgotten to plan that answer, so I winged it: "$3 million." Bryce replied, "How about $2 million?" and I said, without much hesitation, "Okay." So there we raised $500k on a post-money valuation of $2 million - $50k from each of the angels and $400k from OATV. OATV pledged millions more in reserve, if we showed promise.

GameLayers investor Bryce Roberts in his 2007 OATV office - photo by Scott Beale / LaughingSquid.

I graduated with my MFA in June 2007 and turned down a well-paying offer from Yahoo! Games to architect a metagame of badges and points across their service. The deal to fund GameLayers, Inc. closed in July 2007. M graduated with her undergraduate english degree in May, and joined J.J. Abrams' production company Bad Robot as a receptionist, training to use the 3D printer. M left that job after a few months to be chief creative officer of GameLayers. Duncan, our play prototyper, became our CTO, I was the producer and CEO -- we were now three co-founders making a new online experience!

M and I were living in Culver City, near Los Angeles California. Mark Jacobsen and Bryce at OATV strongly encouraged us to move the business from Los Angeles to San Francisco, to be near more developer talent and to be near other internet companies for collaboration.

Bryce, M and Richard one month after the money landed, at a party in the OATV office, on the eve of the October 2007 Web 2.0 conference.

The money didn't actually arrive until September; one of the first great lessons: securing funds takes longer than any prediction or arrangement. That month we packed ourselves and our dog Pixley Wigglebottom into a U-Haul and drove north to a large cheap loft in East Oakland, near San Francisco, where so many other internet startups lived.

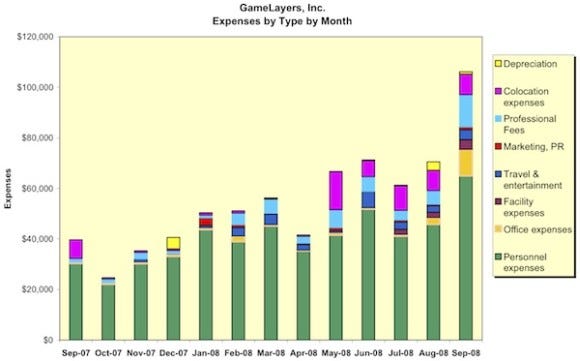

Now we were charged with building out our company. We spent $5,000 to buy pmog.com. During fundraising I remember hearing that you could estimate the costs of running an internet startup at about $10k per full-time employee per month. That includes everything -- overhead, salary, technology -- and it actually works pretty well as a formula. So we went up to about six people, burning about $60k a month, which meant that we had a little less than eight months to prove PMOG could be a viable business and GameLayers could be a viable company.

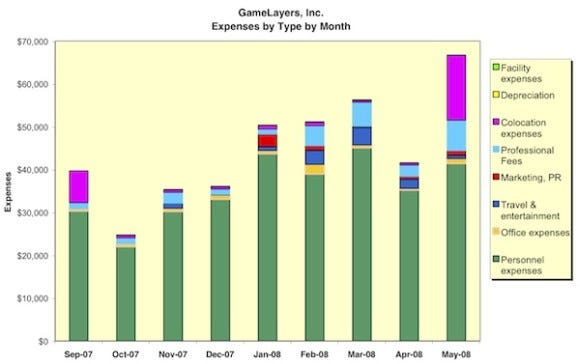

Here's how we were spending our first round of money - mostly salaries!

In reality, we spent the money slower than we predicted. It was harder to hire people than we expected. We saved money by working out of our home. We recruited folks we knew; our first employee, web designer Cap Watkins, was M's friend from USC; he slept in our East Oakland loft with us and our dog until he found his own place.

Cap and M work in the GameLayers loft in East Oakland while Carl Dreyer's Passion of Joan of Arc plays on the landlord's plasma TV - photo from December 2007

Duncan remembers "when we secured funding from OATV and had a conference call with [an] extension-building company, where we almost gave up a large chunk of the company in order to have them build our extension." It seemed like a fast way to get our game running, but we realized we wouldn't be able to iterate our own product if someone else built it. So we decided to hire up a team instead. As Duncan put it, that "was a real challenge, and a test of our self-confidence."

One of our first advisors was Ben Cerveny, a well-connected digital nomad who had worked between the web and gaming for years. Ben helped us find a playful contract artist/programmer Mark "heavysixer" Daggett in Kansas, we reworked our basic sidebar version of PMOG to have a more integrated HUD and a gourmet steampunk look. We chose steampunk because we felt like the genre was on the rise, and it was appealing to internet early adopters. We thought steampunk would also help to distinguish us in the broader games marketplace -- stylish, playful nerdery.

We launched PMOG in closed beta in February 2008 -- people could play, but only with an invitation. This allowed us to gradually grow the game, to be sure our servers held up and we weren't getting overwhelmed with new customers. We had a signup form for people to request access; I would scan the email addresses for the words "venture" or "capital" or "investments" or "partners" or "fund" -- this way I found a number of venture capitalists had signed up for the PMOG beta. I would reach out to each of them to see if we could book a pitch meeting.

Justin, M, Duncan - February 2008 - photo by Bryce

February and March were a big roadshow, talking to the press:

TechCrunch: "Play A Multiplayer Online Game While Surfing The Web: PMOG" by Michael Arrington

MIT's Technology Review: "All the Internet's a Game" by Erica Naone

Wired: "A New Type of Game Turns Web Surfing Into All-Out Information Warfare" by MJ Irwin

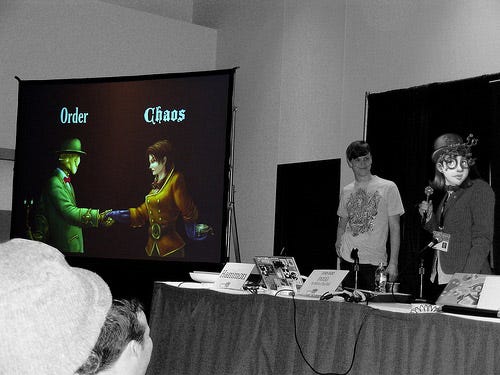

We presented "passively multiplayer online gaming" at conferences: Game Developers Conference in San Francisco (coverage), the Emerging Technology Conference in San Diego, and South by Southwest in Austin.

Presenting "DataPlay: Living Games" at South by Southwest (SXSW), Austin, March 2008 photo by Narisa Spaulding

In our company IRC chat room, with people from the UK, Missouri, Kansas, San Diego, and East Oakland, we worked to evolve our experience, about six of us. Two and a half coders, a front end person, a community support person, a producer, and a game designer/writer. Not enough engineers, but we couldn't hire many -- during a technology boom, engineers are scarce. I pitched in making web views as the producer (the views, and occasionally controllers, part of Ruby on Rails' MVC).

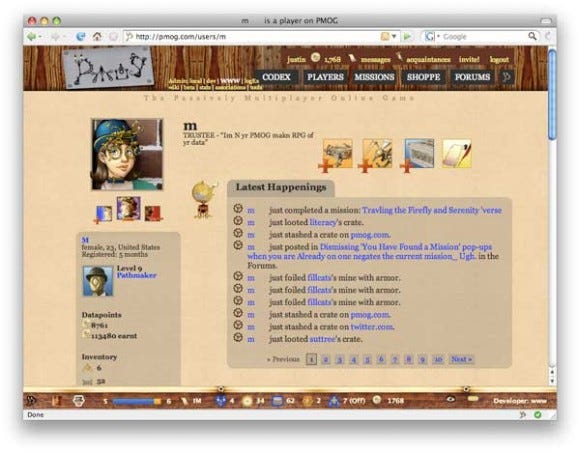

A player profile on pmog.com circa May 2008

Another major lesson from running a software startup: engineers are the dreammakers, and everyone is in fierce competition for talented programmers.

M envisioned a virtual world on top of the internet: a battle between order and chaos, where we supplied the information weapons. For charitable sorts, there were crates for treasure to be left on web sites. For aggressive provocateurs, there were mines that exploded and shook your browser window when you hit their target URL. Surfing with our toolbar game on at times made the internet feel alive with play in the margins!

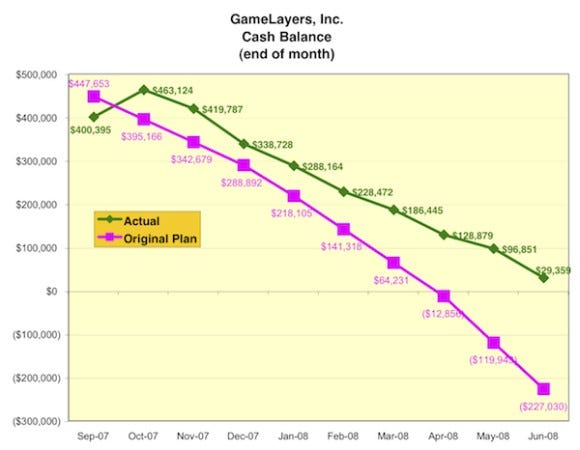

Money is running low towards mid-2008

In the spring of 2008, it looked like we had a promising game service that was getting a lot of buzz. We were spending slower than we'd planned, but we were running out of money. So the game designer/writer M, and myself the producer, shifted to fundraising for about 14 weeks of March-June in 2008. This is a huge attention-suck: tracking down introductions and opportunities, developing presentations, taking feedback, corresponding, prioritizing, traveling, pitching.

I started off with a stupidly fat slide deck. I thought it was important to walk through people through the idea, the history of the idea, the market context, the team, the upside, the plans. But a rigid linear presentation was anathema for busy people who have seen a ton of pitches. Each VC had their set of questions and usually couldn't sit through more than three slides.

Here's a PDF of our pitch deck from March 2008: 200803-GameLayers-SeriesA-09.pdf - 26.6 Megs, 62 slides

Two months later, we had changed our pitch style. Here's a PDF of our pitch deck from May 2008: 200805-GameLayers-SeriesA-22-Shasta.pdf - 15.4 megs, 44 total slides, 8 in the appendix.

We learned to show fewer slides, and then just talk with potential investors. Often these were smart folks with experience building companies, so we had a lot to learn. At best, it was a good conversation, when we learned to relax on the formal presentation. We kept a stack of slides in our appendix; if they asked about "competitor products" or "projected burn rate & operating expenses" or "DAU versus MAU over the last three months" we could pull those up.

There were some soul-crushing moments: taking our hard work into a room with five or six hard-driving rich dudes after a red-eye flight, and they want to know why you don't have explosions or blood in your game. Or why you're not a platform for embedding other people's Flash games. Or why you're so deluded about the size of the market.

We were intent on building one game, because the scale of our team didn't suit supporting multiple products, and we didn't want to spread ourselves across multiple products when we hadn't proven the idea and built a successful instance of this new kind of game. We thought we might build a platform someday -- opening up our tech for anyone to upload their games. But we wanted to get the core experience bolted together first before we supported other developers.

Here's a PMOG Experience video we produced as we were going out of closed beta, circa May 2008.

Early June 2008, one of the craziest weeks of my life:

Saturday: Get Married near Yosemite

Monday: Move from 1400 sq/ft loft to 400 sq/ft apartment

Tuesday: Sign Second Round Term Sheet for $1.5 million

Friday: We fire someone for the first time

In June 2008, M and I were married in Central California. Our investors and co-founder from the UK joined our friends and family betrothing the chief creative officer and chief executive officer of GameLayers.

The wedding ceremony was Saturday. Monday, we moved from our large East Oakland loft into a tiny apartment in an awesome part of San Francisco's Mission District. Tuesday, we signed a term sheet with Rob Coneybeer from Shasta Ventures for a total $1.5 million round that we had just raised after a long roadshow together.

Friday, we had to fire someone for the first time. It was extremely intense running a startup, and being married to a co-founder / board member. Nonshop high-pressure togetherness. We put off our honeymoon and kept working.

Fundraising on an offbeat game on an unproven platform was challenging. Fortunately, we found an investment partner who saw the potential in the widespread social experience we were building: Rob Coneybeer from Shasta Ventures. Rob joined the GameLayers board along with M, Bryce, and myself -- leaving an empty fifth seat we didn't worry about filling.

June 2008: Portfolio.com: "Having Fun, Making Money": "a startup turns the entire web into a game, aiming to steer players toward and away from certain sites. Will advertisers play along?"

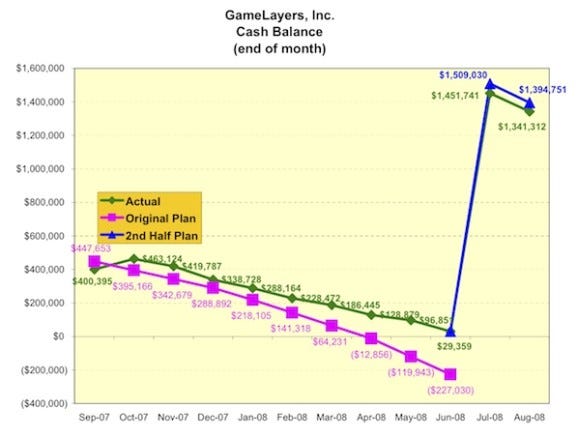

A timely cash infusion arrives in mid-2008!

We raised another $1.51 million dollars -- $1 million from Shasta, and another $500k from OATV. Our two angel investors Joi and Richard had the option to put in another $50k each, but they chose not to. GameLayers was now valued at just under $5 million!

GameLayers Round 2 Term Sheet with Rob / Shasta -- a triumphant document for us.

We were running on fumes when the second round of money came through. Now, August 2008, the money was in our bank account, and we ramped up plans to expand our operations, reach into new markets, improve our featureset, and draw in a ton more users! Rob showed up with a lot of enthusiasm and ideas for the project, giving us a boost of energy. We looked forward to focusing on our game-making again, after months on the road!

Rob Coneybeer from Shasta Ventures, August 2009 photo by Elliot Ng

Our first venture capitalists, OATV, primarily work with nascent startups. Bryce focused on helping us build a team, and helping us get a rhythm building and releasing software. Then Bryce helped us present ourselves as a valuable company for other larger VC investment. Our second VC, Shasta, was accustomed to blowing out a product with promise, making it grow seriously fast. Rob wanted to see progress and drive momentum.

Moving into a new office - photo from 1 September 2008

One year after we started, we finally stopped working from home and moved into an office: 76 2nd Street, the top floor of an old building, for about $3100 a month, space to grow into for 14 people.

Boosting our monthly OpEx spend

One of the biggest challenges for me was learning to prune my stories. I would get a call from Rob at 9.30pm on a Tuesday. "How's it going?" I would immediately start listing the bugs that were on the top of my mind, the problems we were working to solve.

Looking back, I believe Rob wanted to know how we were doing strategically, and maybe a sense of confidence from me that we were kicking butt overall. I've been a journalist for years; in this case, my urge to tell a compelling human drama was not necessarily compatible with "Here's a clear path to acceleration and growth." VCs aren't looking for spin, but I think they want to know that if you're thrashing on bugs, it's part of a coherent larger vision.

Becoming a CEO and raising this money was committing to kicking more ass, sooner -- an exhiliarating proposition. And because I believed in our idea, I wanted to drive it forward as fast as possible. I charged in, learned everything I could from books, advisors, news, and worked to be the best possible CEO Decider Visionary Leader Capitalist.

But occasionally I was too in the weeds -- scavenging on Craiglist for deals on monitors and printers to save $100, when tens of thousands of dollars of employee time was hurtling forwards towards a moving target.

Running a startup is a crazy range of affairs to manage: the unceasing search for engineers, customers having weird issues with common computer setups, investor relations, the mood and productivity of the folks who gave up other opportunities to join our cause, the amount of cash in our bank account, our landlord refusing to install heaters so employees are buying USB-powered heating mittens, state-by-state tax and liability law, we're not paying ourselves much and we're eating out constantly and we're paying rent to live close to the office in one of the world's most expensive cities so personal money is tight, someone else just raised 3x as much money as we did to do the same thing with a larger team. And OMG the entire world economy is cratering!

Justin Hall, Pixley, Terry Thurlow, Alex Friedman, M, Seraphina Brennan, Kristin Nienhuis, Brian Bommarito, Duncan Gough, Joe Wagner, Marc Adams - GameLayers team in November 2008 -- this is as large as we got. Photo by Beth Amann.

In November 2008, the board met for dinner at a SOMA restaurant called Salt House: M, Rob, and Bryce. Rob and Bryce suggested GameLayers needed a new CEO, and my wife M agreed: we needed a firm hand to turn this into a business, someone who could raise confidence with another round from more heavy-duty investors; someone I could learn running a company from. I had gone from game journalist, to game prototyper, to game company pitchman, to game company head, and now I had some reckoning to do. I was not providing leadership for GameLayers that left my board confident in the future.

Time for me to search out a person better suited to my role at GameLayers! That was an intense ego slam. We spent $33k (first installment on a $100k retainer with the Cole Group) and a parade of CEO candidates came through. It was a fascinating experience to meet guys who believed they could make our company evolve and succeed.

After interviews, I didn't think many of them were smarter or better-suited to the role than I was. I appreciated the chance to browse smart potential CEOs, but I also occasionally resented spending upwards of 20 percent of my time trying to replace myself. It seemed like a confidence game. Could I learn enough and re-apply for my own job, owning the confidence of my investors and my co-founder? Or was I better off in another role, leaving the brass tacks of business to someone else so I could focus on building a successful product experience?

The global economy tanked before we could find a replacement CEO; I stayed on by necessity. We were running out of money to pay salary for a big new CEO, and with the stock market plummeting, we couldn't expect to raise another round quickly -- we had to make PMOG succeed with what we had.

Fortunately, through our executive search, we found an amazing advisor Michael Buhr. Michael was an executive at eBay and the CEO of StumbleUpon, a Firefox toolbar helping people experience the breadth of the web.

Fortunately, through our executive search, we found an amazing advisor Michael Buhr. Michael was an executive at eBay and the CEO of StumbleUpon, a Firefox toolbar helping people experience the breadth of the web.

Michael had worked at a 1990s game console company called 3DO, but he wasn't deep into games. Instead, Michael knew about motiviating people and executing on business objectives. Michael was a great manager, a great leader, and he became our advisor and executive coach.

For a few hours a week by phone or in-person, Michael helped us shape the short story of the company, putting forward a vision for concrete action. He sat down with the founders and asked hard questions so we could substantiate our plans.

Michael would have been an ideal CEO for GameLayers -- he understood the Firefox toolbar space, he would have given us freedom to run product within business constraints, he was fanastic to work with. We left every meeting with him feeling smarter and more able to have fun at a challenging job. But Michael already had a job, and wasn't drawn in by the opportunity to lead GameLayers.

Michael explained to me that a CEO needs to be able to state his or her primary objectives at a moment's notice. What is your core focus? Use your core focus as a razor -- everything else is distraction.

In late 2008, we wanted to get more users to play our game, get them to be more active once they started, and get them to make friends and invite more folks into the game. We called these three things Accessibility, Engagement, Social. Then Michael asked us to name three to four efforts we were undertaking to move each of those forward. Here's our December 2008 GameLayers strategic priorities document, the type of focused thinking we developed with Michael's help.

We renamed our game from PMOG to The Nethernet (TNN); perhaps calling it a place instead of an acronym would make the product more tangible and accessible. The Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences nominated PMOG for MMO of the year for 2009; we lost to Blizzard's World of Warcraft. We had more attention, and we scored a huge distribution deal -- being a recommended Firefox plugin by Mozilla. Suddenly we had a ton of traffic, and our servers began to groan.

March 2009 -- a meeting in the chilly GameLayers conference room

We had an active, thriving community. One of our early hires was a part-time community manager: Joe Wagner, a San Diego State University student with a passion for online game community. He helped surface issues from players and communicate our intentions to the passionate fans.

We were consistently honored and delighted by the folks who shared our game with us. They made a podcast, the Tubenauts. They ran a gambling circuit using our currency. They made thousands of guided tours of the web. They banded together to create games within our game. They stepped up to serve as stewards: guides, ambassadors, chaperones, and unpaid expanders of our game world. They supported us, expanded our vision of what was possible, and made us believe that we were helping bring beauty and delight to citizens of the web.

The Nethernet toolbar in the spring of 2009, your HUD for information warfare on the world wide web! So many buttons! There's around 28 things you could click on here: tools, weapons, powers, community, communications.

These days, I would do a full day of 10 to 12 hours at the office, then have some dinner, maybe a beer and a bong hit, and work another four hours or so. I avoided caffeine nearly throughout; light substance use in the evening allowed me to unwind briefly and then plunge back in with renewed vigor. Sometimes, late at night, I might sneak in some work on things like GameLayers promotional vids to post on YouTube and hopefully find new audiences:

Promoting The Nethernet in Japanese

Promoting "Reverse Sheep" a game our players built using our forums

Promoting an alternate reality game that M ran using our in-game tools, a sort of mini-campaign of a literal scavenger hunt solved by the community. We built fake web sites with embedded PMOG data and other URLs. This was a promo video.

Working long-distance with our Dartford, UK-based co-founder and CTO Duncan Gough had allowed a round-the-clock approach to running GameLayers and building PMOG. We would chat in IRC continually, just before each of us went to bed, and check back in, in the morning. All of us chained to our laptops in different time zones, watching the servers hum, hacking on code, design, Google Docs, Keynote slide shows, Photoshop, TextMate, Ruby on Rails, Capistrano, memcache, Highrise, GitHub, hiring, staffing, management, strategy, focus.

After two years of that we needed to have GameLayers working in one shared location. Getting Duncan a visa to move to the U.S. had been an expensive challenge, and Duncan couldn't move from the UK to SF, so we parted ways in March 2009.

Here's a snapshot of what was happening that month, and stats from our game: the April 2009 Board of Directors presentation: 200904-GameLayersBoard.pdf 16.6 megs, 41 slides.

A puzzle crate on a web site showing The Nethernet in its most polished state, Spring 2009. If you answered correctly, there was probably a prize inside, if there wasn't a nested prank! This is a puzzle crate on the Colorado School of Mines, and mines were the most popular weapon in the game. Let the surfer beware!

Now we had a lot of traffic, overwhelmed servers, and no CTO. I devoted all my time to finding a replacement, and a recruiter lead us to John Cwikla. He had the exact experience we felt we needed: he'd taken products with some potential, and some stability issues, and gave them a solid software foundation from which to grow. A veteran of multiple startups, Cwikla hit the ground running as CTO in May 2009. We revised our infrastructure some, and prepared to exit "beta" -- to launch a product to earn money.

Now we had a lot of traffic, overwhelmed servers, and no CTO. I devoted all my time to finding a replacement, and a recruiter lead us to John Cwikla. He had the exact experience we felt we needed: he'd taken products with some potential, and some stability issues, and gave them a solid software foundation from which to grow. A veteran of multiple startups, Cwikla hit the ground running as CTO in May 2009. We revised our infrastructure some, and prepared to exit "beta" -- to launch a product to earn money.

PMOG / The Nethernet was expensive to run. We had built prototypes to prove ideas; we hadn't built something that was conservative with computing resources. We had thrown money at web hosting, figuring that our hosting costs would only grow more expensive if we were successful. Cwikla rigged up The Nethernet to run using the cloud, basically preparing the software to scale inexpensively. Unfortunately, we were chained to a dedicated cluster server and service contract with Engine Yard from before his time, that ran us around $20k a month. I worked to lower our monthly bill, but Cwikla's code couldn't immediately trim our overhead.

Mid-2009 we were pressed up against a wall, watching the money remaining steadily decline. Sad times. We took salary cuts, we laid people off, including our talented, optimistic UI/UX designer Kristin Neinhuis, and a promising writer Seraphina Brennan. We had tooled around with innovation, piling features into our web browser game.

But when it came down to it, we hadn't baked-in monetization. We had a few ideas for earning revenue from The Nethernet; based on our small traffic size and custom platform, selling ads seemed to be an uphill battle. Plus the most popular Firefox extension was about avoiding advertisements (Adblock Plus). So we thought, we'll give people the basic toolset for free, but we'll ask them to pay for the more crafty and crazy tools. Microtransactions!

We called the currency "bacon", which was a sort of inside joke in our player community, and we had fun talking about bacon as a currency: "bring home the bacon", maybe units of currency could be called "bacon bits" and so on. We launched monetization in a hurry, and made a few key mistakes: we took away powers players had already and started charging money for them. We didn't give players much warning.

Selling bacon and monetizing The Nethernet was an abject failure. Plenty of vocal players hated what we'd done. Some folks understood why and were generous -- one woman even ordered us a mega-pack of beer in congratulations. But there weren't enough spenders. We made about a hundred dollars a day the first few days. Within three weeks of launching monetization, we were averaging under $20 a day. $20 a day is $600 a month; two orders of magnitude off from where we needed to be. Considering we had a burn rate over $60k a month, we were profoundly far away from having a sustainable or profitable game studio.

When we launched PMOG we called our new players "shoats", a word we discovered that meant "young pig." Ultimately, with The Nethernet, we weren't able to turn the shoats into bacon!

One of my favorite images from PMOG: a shoat eating a book. By Douglas A. Sirois, a talented illustrator. I had this classy, happy, info-eating pig on my CEO business card until we became The Nethernet.

We felt burned by the Firefox toolbar market. Reading stuff like "who would pay for anything in a Firefox toolbar?" from our players meant that we felt like we were a long way away from sustaining our company on that platform.

It had been a gamble to build the first big multiplayer social game in a browser extension, and it looked like fail: the world wasn't ready, or didn't need what we were building.

We had about $500k remaining at this time. I drew up plans to fire everyone except one programmer, to see if we could keep things running and figure out where to find some more investment or revenue.

Marc Adams was a former U.S. Navy SWCC who was accustomed to 30 hour coding marathons at least once per week.

Even working remotely from St. Louis, Marc was so plugged into our pace that it felt like we could maybe sustain the company on him alone. Marc was profoundly committed to his craft; he was an inspiring engineer to work with.

Marc Adams - Engineer, Photographer - photo from October 2008

Michael Buhr suggested we look at the last $500k as money we could use for a another startup. Maybe t would work if we had a small slice of a much larger pie: we had a functioning, kick-butt web games team, and we refocused on the most profitable market within our reach: Facebook games.

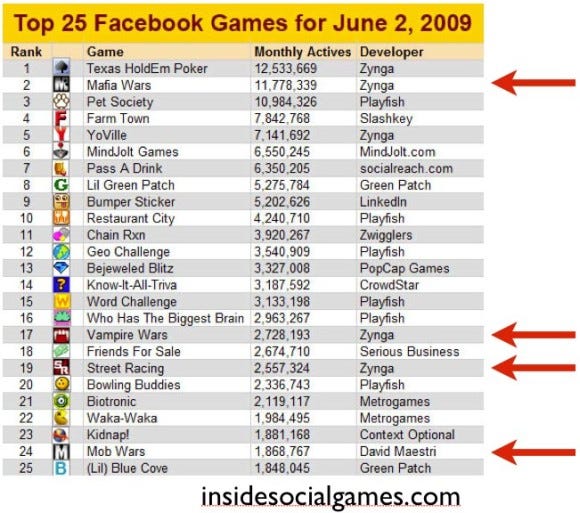

Where's the money and the action in online social games? June 2009 from insidesocialgames.com - red arrows point to "Social RPGs", the type of game we aimed to make.

This was June 2009, and social RPGs like Mafia Wars were tearing up the charts and making good money (a game called Farm Town had just debuted at #4). We were a Ruby on Rails shop; we didn't have any Flash experience. We decided that we could build a social RPG in Rails in a few weeks, then we could skin it to target different demographics. We figured that we could have multiple games up on Facebook within a few weeks.

So we shut down our toolbar game PMOG/The Nethernet, because it was a huge drain on resources and focus. That was sad, but it was easy because we were losing money so fast. In the absence of PMOG, some of our most active and frustrated players went on to create Nova Initia, another browser toolbar MMO of playful annotation.

Meanwhile the five of us -- Justin, M, Cwikla, Alex, Marc -- built a social RPG game engine that could be rapidly re-skinned. For the first skin we chose a geopolitical theme, taking Mafia battles and doing them bigger and more tough: Dictator Wars. We made the theme cartoony to sanitize and parody the horrendous political content. Here's a YouTube video promoting Dictator Wars.

Meanwhile the five of us -- Justin, M, Cwikla, Alex, Marc -- built a social RPG game engine that could be rapidly re-skinned. For the first skin we chose a geopolitical theme, taking Mafia battles and doing them bigger and more tough: Dictator Wars. We made the theme cartoony to sanitize and parody the horrendous political content. Here's a YouTube video promoting Dictator Wars.

I spent 10 weeks reading books about dictators and writing out content for our Dictator Wars content spreadsheet; it was fun to be a bit of a writer again. From books like Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader by Bradley Martin and The Emperor by Ryszard Kapuscinski, I learned terribly sad things about the worst possible violations of trust between leaders and citizens.

I had dreams about dictators for years afterwards. I amused myself by tweeting secretly as the_kim_jong_il, scheming to build a viral social media campaign for our twisted game.

We didn't want to fail as a studio because we'd only targeted one macho audience. So we went immediately to work on a second game, targeting women: Super Cute Zoo. We thought we could add some Flash pets and an improved UI and attract multiple audiences to the basic spreadsheet RPG gameplay.

We five people launched two Facebook games in 14 weeks. It was a long march of long days. After years of having made one sort of game, we had to start all over to make other kinds of games. We succeeded at our mission -- we rebooted our studio! We got some nice press coverage from Inside Social Games: The Road to Dictatorship. We were contending on the most exciting new platform for online games!

We had to learn about Facebook fast. For example, in 2009, each Facebook user got a certain number of invites per day. Because we were fiddling with our game, we had our allocation reduced from 30 to 4 invites a day. That was a huge penalty, a giant growth slowdown for weeks, when we only had months to live.

We spent a little bit of money on pay-per-click install advertising. But we soon learned that other games were spending 10 or 100 times as much money. We were advised to spend $50k our launch week, to place on the charts and get noticed. We didn't have that kind of money, and unfortunately we didn't have that kind of time.

Facebook games were changing fast. Increasingly, farming games were all the rage. Players were expecting higher levels of interactivity. More polish. Our zoo-themed game seemed strange as a social RPG -- any game that promised you a chance to build a zoo wanted to be point and click, and instead Super Cute Zoo featured reading on static web pages.

Here's a stats snapshot, mid-October: Dictator Wars has 28k registered users, with 1700 a day playing (about 6 percemt). Average revenue per day was $53 -- about 3¢ per daily active user. The game was growing by about 100 people per day -- a paltry .3% growth rate (damn our constrained Facebook invitations!)

$50 a day is about $1500 a month; we needed 40 times that or more to sustain our company. We had busted ass, and we'd put something up on Facebook, but we didn't have the time or money to help it evolve into a successful property. With online social games, launching is just the beginning of the hard work.

As part of the second round of funding, Shasta and OATV had secured the right to purchase warrants to the tune of a few hundred thousand dollars. Shasta wanted to be able to buy a larger part of the company at the Series A price if we took off. Late 2008, we voted to extend their right to purchase the warrants, in case we needed the easy cash injection. During 2009, we aimed to be worthy of these cash injections, but by late 2009, there was no additional money coming from our investors.

Here's the last GameLayers, Inc. Board of Directors slideshow: 200910-GameLayersBoard.pdf 3.8 megs, 25 slides.

I spent much of the fall of 2009 calling people I knew who ran social gaming companies, seeing if I could find anyone to buy us, to buy our assets, to hire our team -- to provide job security for our employees and some return for our investors.

I even worked up a patent application for "System for Sharing Tasks between Players of an Online Game" to see if that might increase the value of GameLayers and help us find a lifeline to keep making games.

We had some acquisition interest from larger social gaming companies. But week-by-week, the social RPG format was losing momentum in the market against the mighty FarmVille. Basically, I could see people thinking, "Why buy this company when their games aren't growing that fast? In a few weeks we'll try to hire their engineers, maybe."

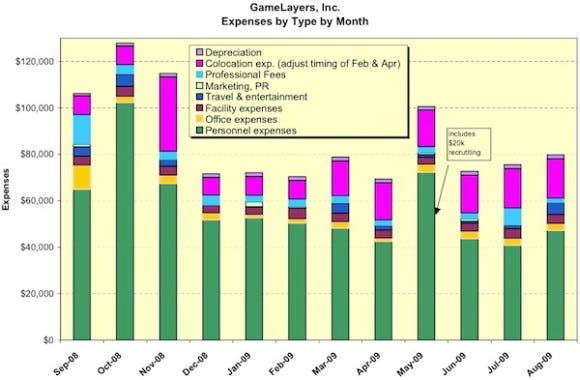

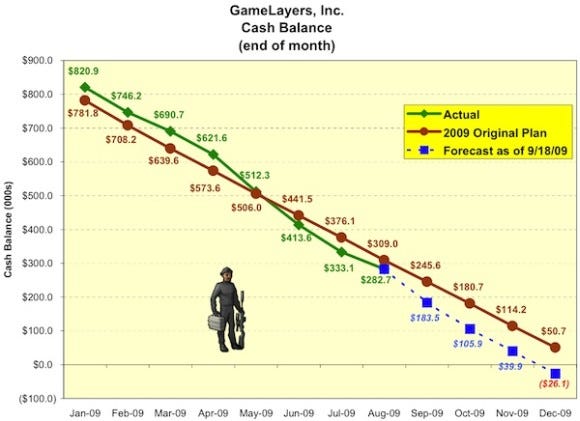

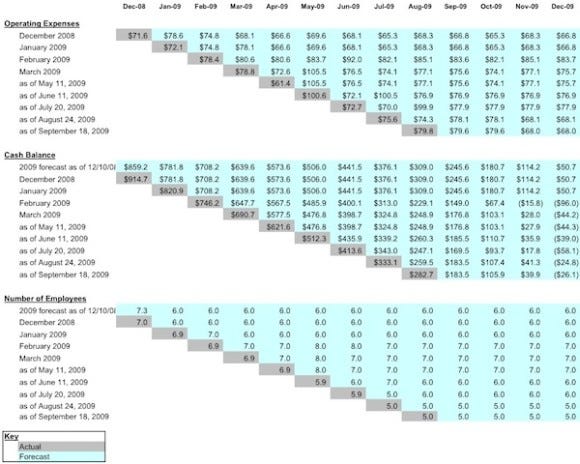

Here's some visualizations of our dwindling finances in last 2009:

October 2009, I was invited to a GameOn Finance conference in Toronto. I blame Jason della Rocca, a relentless connector of people and ideas. Participating there was cathartic -- I really enjoyed a chance to try to save other entrepreneurs from my problems and get inspired by other business experiments. Some nice folks interviewed me and posted it on YouTube.

November 2009 we pulled down our two Facebook games -- they weren't making enough money, and we couldn't commit to long-term service. We took the remaining money to pay off the company's obligations and arranged a decent severance for our people. We laid everyone off, and took a little bit of remaining money to put The Nethernet, our original game, back online to run quietly at thenethernet.com.

What a sobering time! Begging people to pay pennies on the dollar for years of work. Begging people to hire away your best people. And then failing, and calling people who had given so much to this company to tell them I had to stop paying them, and soon they'd have no paid health insurance.

Starting a company is stressful, running a company is stressful, winding down a failed company is stressful. We needed a break, but we were broke.

So we cashed in airline miles and spent on our credit cards to finally take a honeymoon, 18 months after our wedding. December 2009, three weeks of inexpensive tropical luxury on an island in Thailand. January, we returned to the San Francisco area to seek our fortune and pay down our debt.

By February 2010, M got a job as a Producer at Playfish, a social game company. M hired one of the remaining GameLayers engineers to work at Playfish: Alex Friedman, a persistent gamer/programmer who we hired out of college based on his combination of game design and engineering chops.

I helped our tireless engineer Marc Adams find work with Facebook-game maker Turpitude Design. In March 2010, I got a job as a Producer at Ngmoco, a mobile social games company, working with an old friend Alan Yu. Ngmoco soon hired our community manager Joe Wagner.

Alex, Joe, Justin - GameLayers SF Social Game Making Reunion - photo from June 2010

In mid-March 2010, I presented a version of this story at the Game Developers Conference, announcing that we were going to open-source our multiplayer client and server software. Six months later the code emerged in the public domain. Maybe it can be of use to some budding online social play experiments!

https://github.com/gamelayers/PMOG-OS - the server code for PMOG / The Nethernet

https://github.com/gamelayers/PMOG-FF-EXT-OS - the client Firefox extension code for PMOG / The Nethernet

Terry Thurlow was our consulting finance director. She was recommended to us by OATV when we raised our first round -- paying her an hourly rate would ensure that we had all our paperwork in order for future financial events. Having a consulting finance director was a great aid, from day one until the day the lights went dark in our bank account. Terry had experience at Industrial Light & Magic and CollabNet, an open source framework, plus Foxmarks -- she was well versed in the many various trauma of business operations and it was always entertaining to run numbers with her. Plus I really didn't have to worry about the books throughout.

Terry delivers new employee paperwork to Kristin and Brian, September 2008

M and I decided to get divorced in October 2010. I would suggest to anyone that if you're in love with someone, the feeling is mutual, and you decided to go into serious business together, you should immediately commit to ongoing couples counseling with a quality therapist. You're going to need professional third party help to calibrate and prioritize your relationship through the stresses of business. Holy smokes, it's intense.

Founding a company and developing a business was a wild, fast education. By comparison, grad school was a relaxing time to explore ideas and make art. Running a startup was constant adrenaline: you must learn while doing. I'm grateful to my business partners for their patience during my learning time; I'll share my takeaways here to maybe help fast-forward another entrepreneur.

In 1994, I worked at HotWired, launching one of the world's first commercial content web sites. We had to build everything. One of my co-workers there was Brian Behlendorf, who was helping to write the popular web server Apache in tandem with launching hotwired.com. We helped determine the initial size for ad banners on the web. We drove business to Organic, one of the very first web advertising companies. Everything from scratch, on expensive Silicon Graphics server hardware. Hah!

Sixteen years later you can borrow social infrastructure from Facebook, rent a scaling number of machines from Amazon Web Services. Use Google to host your corporate email, documents, spreadsheets, presentations for free. House your corporate memory banks on Highrise for a small monthly fee. There's a plugin or social service for nearly any human interaction you might want to run; you just need to provide a new sort of glue: mixing and matching web services to come up with compelling new ways for people to express themselves, to spend their time and their money.

We started building PMOG in 2006, launched GameLayers in 2007 -- that was just two years before Facebook became the dominant social plumbing for casual online entertainment. We built everything for ourselves -- user profiles, friend connections, message boards, invitation systems. That took up a lot of our time -- if we had started in 2009, we would have used Facebook as plumbing for our social graph and focused on what made our game fun.

Also, cloud computing emerged in 2008-2009. Perhaps the cloud could have saved us from our huge hosting fees and worrying about how many servers to commit to. But we were committed to a non-cloud architecture and that seriously chewed into our budget.

I feel like online service-building has gotten so much easier since 2007 when we started GameLayers; it's fun to imagine this tech being even more accessible in another few years! Hurrah!

Being CEO taught me to focus on a few key priorities. I learned to be ready to present a focused summary of our biggest opportunities at a moment's notice: here's who we are, here's our big vision, and here's how we're building to succeed.

I learned that companies are started by ordinary humans with big ideas -- who then convince other humans who have money to support that dream for a finite amount of time. I learned that people with money also have ideas, and its important to understand accepting money means you're going to be spending time aligning yourself with them.

Being accountable to my board of directors on a monthly basis was helpful: I had to pull my head up to look at the business objectives and present them to a discerning crew.

I learned that the more of your idea you can build without financial support, the more leverage you'll have when it comes to raising money and attracting interest.

I learned that $300 / day is a great "lifestyle business" -- $300 / day supports one or two folks making something they believe in, catering to a particular market. But $300 / day is death for a five to nine person startup. If you've raised venture capital, you're aiming for $3,000 / day, and $30,000, and beyond. Sometimes it seemed like maybe PMOG would have been a better "lifestyle business", meaning if we had prototyped and then started making money off the bat, we would have pulled down maybe enough to support the three founders at a smaller scale with something manageable. We could have grown PMOG organically, gradually, at a breathable pace! But we decided to go for an amazing accelerated roller coaster ride instead, to pour gasoline on a small campfire.

I learned that you can prototype an incredible viable product with people in far-away places -- but it's hard to move truly fast when you're not in the same time zone. Ultimately being in the same room with people is a profound accelerator for collaboration and productivity.

I learned that engineers are the most important part of software startups, and hiring a lot of engineers is a good way to ensure you can evolve fast and increase the value of your organization. I learned there's a metric shit-ton of competition for engineer hiring; it's laughable. Every startup that has a web site with a jobs section with "engineer" positions listed. Fierce competition!

I learned to value the chance to meet with CEOs from other software startups. I would drive to Palo Alto or Mountain View to talk to these people facing similar struggles. It felt like community; I got great wisdom. Usually I tracked them down because we shared an investor or a common friend. Several OATV companies were funded at the same time (Get Satisfaction and Instructables) and we ended up having group OATV-funded executive dinners every few months -- great camaraderie with people as busy as we were.

Alan Yu was a friend of ours; he was working at Electronic Arts at the time. He listened to us describe PMOG over sushi one night in SOMA. Alan suggested that between gameplay, theme and platform, it's advisable to limit innovation to one of those three when making a new game. With PMOG, we were doing an unusual game (leaving information tools on web sites for other people) with an unusual theme (steampunk was not mainstream) and we were building a massively multiplayer online game for a platform that had never really seen much of a game on it before (Firefox only had a few very basic arcade games, and one attempt to build multiplayer Pong). Now I think more about focusing innovation, creating a more approachable experience for game players.

I didn't have much time for reading while I was in the midst of this software startup, but I read Jessica Livingston's book Founders at Work. Founders at Work was hugely comforting to me, as I read of all manner of small software business permutations; people who succeeded and failed and pivoted and dealt with all the complexities that were so a part of my life.

Daniel James was actually part of my education from an early stage -- because he shared his data year after year with the audience at the Game Developers Conference, and then on the web through his site The Flogging Will Continue Until Morale Improves. Here's a sample presentation: "Metrics for a Brave New Whirled" -- transparent about data most companies guard.

I've learned to see more of the entire ecology of media/software innovation: from the limited partners LPs who fund the Venture Capitalists VCs, funding and prodding the founders and executives. I've been a disgruntled employee who doesn't understand why a company doesn't hew closer to its ideals; now I see so much nested economic activity that I tend to bite my tongue before critiquing corporate actors.

I learned that distracting employees should be laid off immediately. Firing people is hard, but if you're a startup founder debating whether someone should be fired, they should be fired. There's such a limited amount of time with a focused team; in a company under 10 people, one underperformer brings everyone down and ties up invaluable time. I learned to think of firing someone as "helping them find a more suitable opportunity", because if they aren't thriving at your company, no one wins.

Laying off people was a fucking serious painful thing because these people were doing important work to drive the company forward -- but we just didn't have the money to survive. It's a sobering, terrible thing to have to say "goodbye, farewell" to someone who you've asked to give up other opportunities to join your crazy mission that could be a great success for everyone involved, if only we weren't months from cash-related asphyxiation.

First I developed the reflex to test "I have a cool idea" against "I wonder if it would pay for itself?", and then "I wonder if that's just a lifestyle business or a real company?"

Through the company ending and the divorce, I, Justin Hall, now own the code, art, trademarks, and URLs for The Nethernet, PMOG, Super Cute Zoo, Dictator Wars and GameLayers. Wow! It's all worthless unless someone invests more time and money to make something compelling from those bits, bytes, and ideas. Social games require paid servers to run, engineers to keep them alive, community managers to run events and designers to make new content. None of this stuff runs without constant tinkering. So all these assets are aging quietly on hard drives awaiting purpose; at least the code for PMOG is open source, so it might have life beyond.

The Nethernet is up and running today, paid through 2011 -- maybe you can play it with a copy of Firefox 3 and a link to http://thenethernet.com/. Bless 'em, there are still players as of September 2011, two years since we worked on the game. By 2012 it will cost about $100 a month to host. Who wants to pay that? Paying down a year of credit card debt after my startup doesn't make me too inclined to support the game personally.

Twenty years from now the "social games" of the 2010s will be screenshots, but not anything anyone can play; without servers you can't boot up and run a social game.

I will confess I haven't played The Nethernet in a long time. I actually switched browsers -- I needed to clear my head, and now the game only works in Firefox 3. Rebuilding it for Chrome / IE / Safari is a challenge; maybe we could somehow port it to a floating HTML5 pallette, or some other web hackery.

Maybe some day, we'll have a Kickstarter-type fundraising campaign to keep evolving this thing. I'll be keeping an eye out for projects that make use of the open source code! And I'll be keeping out for people who evolve the idea of games embedded in our daily activites, and social play across information space.

If The Nethernet is online, you can see where the action is from the feed of in-game events or the latest posts in the Forums.

I still have this California "PMOG" license plate -- during GameLayers, I figured, why not advertise the game in traffic?

I threw myself into this startup. It felt like a combination of a cause, a lottery ticket, an identity, a vehicle for realizing a better me, and a better life for my family. Looking back, I savaged a number of my relationships through inattention and stress. I might have made a better CEO if I had taken some time for hobbies, reading, chatting, travel -- some life balance. But I can still remember life in the startup trenches; I felt so important, like my every minute could feed this hungry entity and make it more likely to succeed. I felt so profoundly responsible, and I got off on that feeling.

After being CEO of a startup, being a producer at Ngmoco was so nice, because I could just focus on making a product, to not worry about payroll and investors. Working just 60 or 70 hours a week feels like a relative vacation. Being CEO meant I woke up at 4 am most days in sheer panic about any one of a dozen looming madnesses. Now I wake up at 4 am mostly because I had spicy garlic noodles.

I feel like my churning mind lent itself naturally to running a business. I like to deliberate over potential future issues and opportunties. John Lilly was at that time CEO of Firefox, and we had some useful meetings. He advised me: "don't borrow problems" -- don't worry about things you can't control. Lilly also suggested being a CEO is often about looking over multiple fires and deciding which fire needs water most, because you can't ever put them all out.

I now understand that most businesses don't succeed. While success is rare, opportunities to learn and evolve are limitless. My investors were gracious to the end, explaining that they knew they were taking a risk when they invested, and they appreciated the work we'd done to make a good go of GameLayers. I see them every few months now.

Months after GameLayers ended, I heard about another failed startup -- this one had been funded by family members. As a result of the startup failing, someone had a mortgage they couldn't afford, and there was bad blood between the businessperson and their supportive kin. So I'm glad I worked with professional investors; they shared valuable experience, and they could afford to take a chance on this idea without painful loss.

I felt supercharged being responsible for a shared destiny, and though it didn't work, I would definitely do it again with the right concept or team. Work is best when it's fun and meaningful. Next time I would want to have more balance in my life; exercise, socializing, family time. But maybe I'm just saying that because I'm older. I'm not sure whether I'd be a good CEO again; I'd definitely do better than last time. Mostly I'm excited to pitch in wherever I can with compelling people and amazing ideas on crazy challenging new networks.

We saw three competitors start up: RocketOn and Wello Horld and WebWars, each making some version of "browser plug-in based gaming across all the web". And our players were frustrated when we took The Nethernet offline and so they created their own PMOG-ish toolbar game: Nova Initia. None of these has cracked the code of widespread browserplay goodtimes as far as I've seen yet. Maybe browsing the web and playing a game are two/too distinct activities for most folks.

Flickr was often on my mind: the popular photo-sharing service from the 2000s that was purchased by Yahoo!. Flickr started off as an attempt to make a complex web browser game; a sort of MMO for comparative literature majors called "Game Neverending." The Flickr founders figured out that photo sharing might be a better use of the tech they'd built. I thought about how we might adapt PMOG to other web sharing, but there was no ready product coming out of our toolbar. And we really wanted to make an entertainment experience.

Working at Ngmoco has developed in me an intense discipline for "compulsion loops" -- what are the core activities in a game that keep people engaged? How does one in-game activity lead readily to another? And what is the core fun at the heart of your game? Ultimately, I believe PMOG lacked too much core game compulsion to drive enthusiastic mass adoption.

The concept of "leave a trail of playful web annotations" was too abstruse for the bulk of folks to take up. Yes, being a Firefox MMO was a weird and challenging hurdle to adoption, but people will go to insane lengths for a good time. If we had presented an amazing fun entertainment product with a clear path to fun, we would have had a larger audience. More players would have made it easier to raise money and make money.

We heard the feedback "I don't know what I'm supposed to do" from new players and people who tested it. We thought we could add features or somehow convince people to power through to become dedicated players. Looking back, I believe we needed to clear the decks, swallow our pride, and make something that was easier to have fun with, within the first few moments of interaction. That may have meant scrapping "passively multiplayer" as a game concept, or a toolbar as the mode of interaction. Those were pretty core to our initial business plan, so it took us a long time to see those concepts through to revenue failure.

Then we pivoted: we shifted strategy from "build the best game played across the web" to "build games to learn how to make money on Facebook." We brought our vision in from the horizon to our bank account. It prepared us employees for careers working in social games (four of five of the last GameLayers employees were making social games for Facebook or mobile within six months of the company closing). The sector was hot and we learned it.

But what if we had doubled down on our goal of building a big game? "Okay, so The Nethernet can't support itself. We're going to break apart that technology into something smaller, a simpler game to play across the web" or "We're going to take what we've learned about play across the web and make a big game you can play anywhere on your mobile device." Would we have found a sustainable path by pivoting towards another bold future instead of quick Facebook monetization?

Don't know, can't know -- happy to live on, to see all kinds of new games made on new platforms by new dreamers.

Ultimately, I'm honored and humbled by the chance I had to work with fantastic, motivated, brilliant people each day on dynamic complex problems, to take an idea and make it real, to test our theories on the human market, and to fail with as much support as we rose. We didn't win the capitalist gold medal but hopefully we generated some useful knowledge and entertainment!

The most excellent artist Colin Adams draws a scene from the history and lore of PMOG / The Nethernet: The 12 Year Civil War

This writeup started as a writeup for a March 2010 talk at the Game Developers Conference - here's the keynote from that presentation, a summary set of slides covering this story - 201003-GDCfate-03.pdf 9.6 meg PDF, 23 slides. Here are Raph Koster's Notes on that presentation.

Executives at Ngmoco speak of building "a company of consequence." That sounded powerful to me when I heard it. You can keep score with money earned; you can also look at how much you contribute to or augment the human experience of life on this planet. Barring some insane resurrection, GameLayers will at-best be a memory, or a useful teaching example. Sharing these notes might serve as fuel for other schemers. I think of this article and data as open-sourcing our business process, alongside the software code we open-sourced as well.

This article was originally published on the author’s personal site. The version there will always be the latest and most inclusive: http://links.net/vita/gamelayers

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like