Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Can a new way of developing games save a company? Gamasutra speaks to two Double Fine developers about what the recently ended public Amnesia Fortnight means to the company, and why the failure of Brütal Legend was a blessing.

Over two years ago, while his studio was still under contract with EA finishing up Brütal Legend, Double Fine head Tim Schafer decided to try something entirely new. Dubbed the Amnesia Fortnight, this prototyping festival would see the studio breaking up into several teams and coming up with a variety of smaller game concepts. These prototypes then became games, got signed and changed the studio's destiny.

Schafer detailed this experiment to Gamasutra at the time. How do things work now?

The experiment worked. No more does Double Fine focus on big, packaged console games. Instead, it has concentrated its efforts on doing more and more small projects, continuously turning out new games on different platforms, and trying to forge a future as a mid-sized developer that won't end in the closure of the studio, like so many others these days.

In this interview, conducted the day after the latest Amnesia Fortnight concluded, designer JP LeBreton and writer (and former Gamasutra staffer) Chris Remo discuss the ins and outs of the process and the way the studio works in 2012 and beyond.

This Amnesia Fortnight was the first to put the prototypes up to a public vote, and the first that was live streamed from its San Francisco offices, which had a profound effect on the process.

I'm interested in discussing Amnesia Fortnight, and the evolution of Amnesia Fortnight. I get the sense that Double Fine found itself through this process.

Chris Remo (pictured below): I think that's totally correct. It's funny because, for me -- JP and I didn't work on BioShock games at the same time, but I also weirdly came from BioShock to Double Fine, but the first game I ever worked on was Psychonauts in 2004 as a tester.

I'd known Tim for a long time, and I liked Double Fine a lot, but kind of like you said, it feels like this year Double Fine has really been coming into its own in terms of a very particular identity that's not just the games, but is also every aspect of the studio really representing a certain ethos, or tenor.

JP LeBreton: It's not something as specific as an aesthetic. It's actually a more general approach to trying to do creative work in non-tiny game development. Yeah, it's really awesome and refreshing.

We started working on The Cave in earnest about a year and a half ago, which was right around the time that I started. And then a few months in, I got to be part of the first of last year's Amnesia Fortnight. And then the Kickstarter thing happened earlier this year, and now we just yesterday finished the public Amnesia Fortnight, which was a completely crazy thing. Chris and I worked on a project together.

And so I couldn't feel happier with where I've ended up, and my initial guesses about this being an interesting place to stretch one's wings creatively. It's just an amazing place and time to be there. And yeah, it's awesome working with Ron [Gilbert] and stuff. It's been a great year.

CR: Some of the most amazing and talented and awesome people I've ever worked with were at Irrational, and that was super incredible and super super cool, but the difference is -- like, The Cave is the biggest game that Double Fine is currently in the process of shipping. And it was roughly about 20 people, plus or minus, depending on what phase of development it was in. But that's the biggest team.

CR: Some of the most amazing and talented and awesome people I've ever worked with were at Irrational, and that was super incredible and super super cool, but the difference is -- like, The Cave is the biggest game that Double Fine is currently in the process of shipping. And it was roughly about 20 people, plus or minus, depending on what phase of development it was in. But that's the biggest team.

The difference between a triple-A studio where you have 100-plus people all working on one game, and a studio of 60-something people working on five different games of varying scopes and sizes? It's super awesome.

Irrational has to have 100 people working on BioShock Infinite, and they still have to cut multiplayer? That's nothing against them --

CR: That's the reality of triple-A development. It really is an arms race to some degree. I like that Double Fine has just opted out of it. Since Brütal Legend, it's just --

JPL: Taken a different path.

CR: Yeah. We're doing a different thing. One of the cool things that Amnesia Fortnight shows, I think [is that] as a result of making games like The Cave and all the other stuff Double Fine has made, that's a big reason it's even possible, in two weeks, to make games of such different subject matter and gameplay, but to such a high degree of quality in that amount of time. It's because Double Fine now has this history of making all these different kinds of games with our internal tech, all the same time.

There are all these different competencies that are constantly being honed in the studio on all these different kinds of things. It means -- you were saying, JP, earlier, that it's not that Double Fine has this particular aesthetic coherency that makes up a studio. Part of it is actually the ability not to have to rely on a single one kind of studio aesthetic, because you have all these people making all these different games and constantly stretching their game development muscles in all these different directions.

It can evolve faster. Everything can evolve. It's the people, it's the tech, it's the expertise -- it's even the business expertise, which is just as important to keeping the studio afloat.

CR: We have a relatively new business developer, Justin Bailey, who has just been super-super aggressive and creative about trying to explore every different business angle, as opposed to just pitching to as many traditional publishers as you can.

We still do that as one of our avenues, but there's all of these other interesting ways to potentially get things funded, and he's trying to explore as many of them as possible. It's really cool to see because, well, why not? We're an independent company. We can do whatever we want.

JPL: And our goal is ultimately self-sufficiency, where we can self-publish games and work on the sorts of things that interest us. That's a really tall order. That's way easier said than done, but I think the Kickstarter is a good example -- well, when that's your objective, you go to things like that. Maybe if it hadn't worked out, we'd probably still be trying crazy stuff.

I think the commercial failure of Brütal Legend was a blessing in disguise for the company.

CR: I totally agree with you.

JPL: Because that's what led to the first Amnesia Fortnight.

Look at what happened to other companies. Eurocom, which has been around since the NES, shut down after just having shipped a 007 game for Activision. When they signed that game, I don't think they were thinking, "This was a terrible idea, for us to sign this game with Activision!" But in the end --

JPL: They thought they were getting a great deal. This was a really solid property. It's just a good solid work-for-hire project, but, yeah, it ends up being your epitaph. "Keeping the lights on" has been the epitaph of so many independent studios, and, Double Fine is partly where we are, I like to think, because we haven't been content to do that.

A lot of it is to Tim's credit, because he's been the right combination of conservative, but also willing to take risks and stuff. Part of that is after Brütal Legend, he was absolutely the creative godhead. And he still is; he's the face of the company and he's pretty much one of the most charismatic people in games. But even with all of that, he was willing to step aside and give some of the limelight to the people who led Costume Quest and Stacking and The Cave, where Ron is coming in. And Brad [Muir] is another super-charismatic dude. Being such a big famous game dude, but also being willing to spread some of that around -- it shows the company doesn't just have a single direction that's one man's vision. It's a plurality of things.

And honestly, that's another huge reason that coming from where I did and ending up where I did, that this seemed like such an attractive option to me. It's been awesome working with Ron, and I'd love to start working with Tim on the Double Fine Adventure thing. I don't know. It's just awesome. It's a completely different kind of thing.

CR: On the notion of Tim and the "keeping the lights on" thing, there's something that I think is really important. Obviously, if you're in a position where, "Okay, we need to take this 007 game, because that's how we keep our company afloat," you gotta do it. But I think there's something really valuable in Tim sticking to his guns in the sense that the only licensed game that Double Fine has ever made was a Sesame Street game. That's cool. That's an awesome way to take that first step into that world, is to do it with something like Sesame Street. I think that's awesome.

JPL: And the people who were really hardcore Double Fine fans who loved Costume Quest and Stacking, but also who loved Brütal Legend, heard we were doing Once Upon a Monster and just got it.

Yeah, who doesn't like Sesame Street?

CR: Exactly.

JPL: I'm glad that nerds' hearts are not as icy as we always assume. They're not so icy that they can't admit things that are more lighthearted.

I can't think of how to say this and not sound completely facile, but we all lamented the fact that we couldn't have these kinds of lighthearted adventure games anymore. But now we can -- just, we just have to find a way to do it. It's the flipside of the studio doing what it wants; now you've got to connect with audiences the way that you can.

JPL: It's still a weird question. Being on-camera for most of the last two weeks is weird. It's like, "Okay, this is the new world where, yeah, you're not as reliant on publishers, or you're just making things that publishers aren't as interested in. But now your fans are your publishers, kind of, and you have think about your relationship with them a lot more carefully, or in a much more intricate way than before."

I don't know. I'm sure that will prove in the long run to have its own set of advantages and disadvantages, but it also just feels like a much more honest living, where you're not dealing with a middleman in some ways. That's interesting. Ask me after Double Fine Adventure has come out, and all that, what the final verdict on that will be. But it seems cool. And certainly Kickstarter is also a Wild West of interesting -- but also kind of scary -- ideas and stuff. It's more interesting than publisher hegemony, that's for sure.

CR: Amnesia Fortnight was even weirder because it wasn't even a matter of "This is a thing that we know there's an audience for. Help us make it." It was just, "Here's 23 game ideas. Which ones do you guys want us to make?"

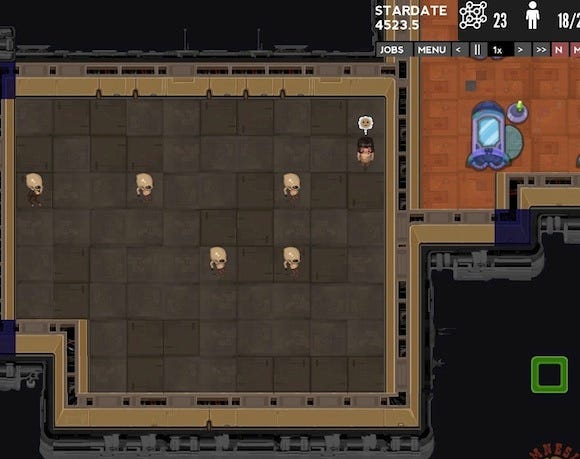

It is super weird, especially because the one that JP and I worked on, Spacebase, is like a weird management simulation thing, and that's a kind of game that even within the brief you give it -- "build a base in space and watch aliens live interesting lives on it" -- even that, you could theoretically take and make 800 different ways.

So not only do you have these thousands of people voting for that idea, you have thousands of people voting for their mental conception of that specific idea. But then you've gotta make one specific version of it.

To tie this back to The Cave, you originally asked this with respect to adventure games specifically, and there's definitely something interesting about adventure games with respect to The Cave. Because Double Fine is working on two adventure games right now; we're about to ship one and we're working on another one. Double Fine Adventure is very overtly and self-consciously a classic point-and-click adventure game in every respect.

Yeah, that's the pitch.

CR: It's not intended to feel archaic, but it's definitely intended to be traditional in a general sense. The Cave kind of is too, but almost deceptively so, in a certain way. You look at it and it's like, "Oh, it's like a side-scrolling platformer." But actually all the things you're doing in it are solving adventure game puzzles and combining items and figuring things out and --

JPL: It's in the clothing of a platformer, but really it's an adventure game.

CR: Right. So The Cave is almost this weird other route to a similar goal. We like what the things an adventure game achieves are, but what's another way we can get there? You're still basically doing the same things. But it strips away -- there's no list of verbs, there's no real inventory. You pick up one item at a time. You've got the multiple characters, which is kind of almost a Maniac Mansion callback. So there's weird little things that are different but the soul of the thing is still essentially a straight-up adventure game. It was coincidental that those two games ended up in development at the same time. That wasn't a plan to exploit adventure games in these two different ways. That's just how the dice fell.

To go back to something you said earlier -- with the new Amnesia Fortnight, I remember when they collated all the votes and they announced the games, Tim started a forum thread saying, "If you didn't vote for a game, tell me why you didn't vote for it." I thought that in a certain way, that was actually one of the more interesting things to come out of it.

JPL: Incredibly fascinating.

CR: Especially for Tim, because in the past, Tim always the guy who would pick all the games. So I could imagine from his perspective, this must've been even weirder than it was for us. He's like, "Oh man, here's this thing that we've done multiple times in the past, and I was the sole arbiter of what got made."

JPL: And I'm sure he had his picks.

CR: And now he has to relinquish. That must've been weird for him.

JPL: But that's another thing. Even though he's a big personality creatively, and the things that he works on he's going to be the game director kind of guy who calls all the shots, he was still willing to abdicate some of that control in the interest of broadening the concept of what the company did, and all that kind of stuff.

And even beyond that, get to the root of not just why people like things, but why they didn't like things. I think that's actually an important, and often unasked, question.

CR: Because presumably a lot of those games that were there, maybe you tweak one little thing about the pitch, and suddenly that becomes one of the most voted games. Who's to say? It's interesting to try and pursue those thought experiments and be like, "All right. This one ended up kinda in the middle of the pack. But are there key things we can identify about it that, once you read all the reasons people didn't vote for it, you realize a few degrees away, this might've been something that really resonated with people, but for whatever reason, the specific way it was pitched it didn't."

JPL: Like, someone was saying that Milgrim would have won if it were called Mario Defense.

CR: Which is probably true.

JPL: But it's weird thinking about pitching games, and the process of getting people interested in them, as a process that's as iterative as game development itself. Because game development, the rhetoric is now, definitely, "Well, you try something, and then you see what's successful and not about it, and then you change it," and slowly just steer it over time based on ongoing feedback.

But doing that for games you haven't actually started working on yet, or games that you're just starting to work on? It's a potentially dangerous thing, because if you don't have a strong creative identity, you'll let your fans just drive the car off the road.

But if you do have that identity, then hopefully you just get input, but then they also trust you to do [it.] I think Kickstarter done right is probably like, your fans are trusting you to make the thing that you said you were going to make, and you have a clear idea of how you're going to get there, and you don't promise anything too specific.

The Spacebase DF-9 prototype distributed as part of Amnesia Fortnight

I can only speak for myself, but I backed Double Fine Adventure not because I wanted to make Double Fine Adventure. It's because I wanted Double Fine to make Double Fine Adventure.

CR: I think that was what was so smart about calling it Double Fine Adventure and not calling it The Tale of the Kid Who Lives in a Spaceship. It's specifically just "an adventure game from Double Fine" and hopefully you think that is conceptually cool in the broadest possible strokes. We'll try to make a thing that is awesome as we can within that framework, but that's a very loose boundary. That can be a lot of different games.

I guess if you're a developer that is specifically making a re-imagining or a sequel to a classic thing you've done, then that makes sense. You can probably assume a certain known quantity. But Double Fine had actually never actually made an adventure game before The Cave. You don't want to get too specific about that, because who's to say nine months in development, what might happen. I don't know. It's been weird.

The other thing that's weird about that game is that people who are not backers have seen none of it. We haven't actually done any PR on that game. But people who are backers, have seen just reams of concept art, and hours of documentary footage, and all this stuff. They're able to, if they want to.

You're talking about the fact that it's departing from the normal PR cycle as well -- everything about this is different.

CR: Yeah, it really is. Amnesia Fortnight was even more extreme in that respect. Amnesia Fortnight was bizarre. It was weird. Every single day we had eight hours of live stream straight from the office. People were watching Double Fine artists just screen-share their work for, like, three hours at a time. Thousands of people across the world were just watching an effects artist literally type things in.

People watch Notch code on Twitch.tv.

CR: Exactly. So I guess it's actually not even that crazy for us. It felt super crazy.

JPL: Hardly anybody's done it.

CR: Watching talented people do things is actually interesting. I hope that a lot of those people watching are game development students, or people who legitimately want to. Because Lydia Choy, Jane Ng and Brad Muir, when they were streaming stuff, they were actually engaging in direct Q&A with the audience and people would be like, "So, why are you doing this?" And they'd be like, "That's because this is useful for this and this and this. I'm debugging this code here, and this is how our effects editor works, and this is how much of it is done via straight text, and this is how much of it is done via sliders." Even for me, someone who's a co-worker of these people, I still found it really inspiring and surprising.

Did the teams form naturally? How does that work?

CR: People filled out a survey listing the games they wanted to work on, in order.

Did everyone who was coming up with a concept that was going to be in Amnesia Fortnight pitch it internally? How does it work?

CR: Technically internally, but also still live on the internet!

JPL: It worked really differently. In years past, we would talk to Tim about it and then we would pitch. This year, we basically just did the video pitches, and those went up. And so we saw everybody's video pitches. Also, there were 23 of them, which is twice as many as we've had in previous Amnesia Fortnights. I guess everyone was jumping at the opportunity to do this crazy thing.

Well, your game could be a game! I have friends who've been working as developers for 10 years, and they've never had their idea become a game.

CR: It's actually incredibly rare. In the games industry, it's really hard to be the guy who works his way up from the mailbag to be the CEO of the company.

And you might end up -- in your case, JP -- not that you had any problem working on BioShock, I'm sure, but it wasn't your idea.

JPL: Yeah, yeah. And the best you can hope for in those situations is just, like, you're one instrument in an orchestra. I think you get that when you're making smaller things, that you're not so much an orchestra anymore as a bunch of bands. And, yeah, you can lead a band or just be part of a band that's a very collaborative thing. And that's awesome, because the orchestra has its own limits. I'm going to walk away from the metaphor...

CR: As a musician and composer I've always found that analogy to be total nonsense. An orchestra is not a unit that creates music. Actually, an orchestra interprets a composer's work. Like, an orchestra isn't in real-time creating a thing the way a band works. So they're actually not analogous.

JPL: Particularly if you have a really strong auteur figure at the head of development, you're kind of like -- some teams, and I kind of feel sorry for them, but they are put in the position of interpreting that person's work. Even though it is more collaborative, and, yes, there the analogy breaks down, and we'll abandon it.

But, I don't know. Just the scale of it. Doing something creative in a group of 30 or 50 or 100 people feels really different from doing it with a dozen people. Game development, I think, is pretty inherently collaborative. Individuals can do it, and should. I'd love to see more of it. But I think small teams, I think it's a balance between the creative freedom that you get from working individually on the small thing and just the big scale and what you can do with production values.

I think, honestly, with triple-A games, we're kind of seeing the limits of production values. You have to make some Faustian bargains in order to bring the big spectacle, and get all that money up on the screen. It ends up limiting what you can say, in some ways. Whereas going broad and going through different ideas, that's wonderful. That makes me more optimistic about the future of games than just what the big huge players are doing now.

CR: To get back to your question about how the games were pitched, after the games were voted on, then the project leads like JP and the other four people who were in the top five, they then pitched the games internally to the studio. But, just like everything else in Amnesia Fortnight, that was still on the live stream being watched by thousands of people, so only technically "internally." But that was the pitch to Double Fine people saying, "Yes, please work on my game."

At that point all of us who were not project leads went back to our desks and filled out a survey, ranking the order in which we would prefer to work on the games. And then Isa [Stamos], our product director, and Tim, and our producers all basically sat in a room and tried to figure out how to put all the Tetris pieces together in a way that would make as many people as possible on the games they most wanted to work on while not shortchanging any teams for not having enough artists or programmers or whatever else. This was actually the first Amnesia Fortnight ever where each team got their own audio person. So that was cool. They had to solve all those resource problems in a way that actually made it possible to make five games to some standard of completion.

JPL: That was very much an internal studio process. That was Tim and Isa...

CR: That was not live on the stream.

JPL: No. Yes. That was very private -- because it does get into some "who wants to work on..." It's a little bit political. Though not in a backstabbing cloak-and-dagger way.

CR: [Film crew] 2 Player [Productions] still filmed that, though. I just remembered now. Yeah, because there are bits of that in one of the 2 Player daily videos.

JPL: "So-and-so wants to work on this." Yeah. So, yeah.

CR: So we're never safe!

JPL: The fact that we're willing to open the kimono that much is just astonishing.

You're just taking it right off.

JPL: The kimono is hanging open onstage at the microphone, yeah.

At that point, once we got our teams, we knew what our teams were gonna be on Tuesday afternoon, and so that was less than 48 hours after the voting closed, and then we were off to the races and doing our crazy game development thing. So that's something that we just did. Yeah.

CR: It's really fortunate that it worked out this way. Middle Manager of Justice came out today, so that's a bit more current, but The Cave is pretty much wrapped up at this point. It was actually really fortunate that we had this period of time during which Amnesia Fortnight could come in and not just ruin things.

Not disrupt life too much. Kinect Party just came out.

CR: This also happened earlier in the year. I remember earlier in the year -- we have a weekly meeting every Monday where the whole company is in the meeting. And I remember there was that period of time for, like, a month, where every company meeting it was like, "Wait, which game came out this week?" I can't even remember everything, but it was a bunch of stuff. Like, Psychonauts shipped on Linux and Mac. Yeah, we make a million games all the time. It's really weird.

But that's why the company's around. I think that's why we put Double Fine on our list of top developers for 2012. Not just because we're like, "Good job, guys!" But we wanted to hold it up as an example to our readers, so they go, "Oh, I could do this."

CR: Yeah, man. I hope so. One of the things that's been most terrifying -- and you're just as aware of this as I am for the same reasons -- we seem to be in this period right where mid-sized developers are just closing left and right. All the time. It is actually fairly terrifying. Being at a company like Double Fine that is being really, really proactive about staying out in front of that trend feels almost like a relief, in a way.

JPL: At least we're doing something instead of holding onto a status quo that's crumbling.

CR: Yeah, exactly. I feel like we have another console generation where stuff effectively works the same way that it does now.

The one that's upcoming?

CR: Yeah. But after that --

JPL: And that might end in disaster.

CR: Who even knows? We just have no clue. I feel like in the past you could be relatively certain about what it would mean for there to be a new console generation.

Yeah, the N64 vs. PlayStation vs. Saturn -- you wouldn't have necessarily predicted that Sega was going to tank in America and that Nintendo wouldn't do so well, and that Sony was going to win.

CR: But fundamentally the market didn't change.

JPL: You didn't know who was going to win, but you knew that the console business model would win. And now I think that's in doubt, especially if Valve is releasing a console. So, yeah.

CR: You were saying, "Why are you on the Wii U?" earlier. That's what's nice about working with the same tech for so many years. We have this slow accretion of additional platform support onto this one engine, and on top of that we're now developing our 2D engine on top of Moai, which supports PC and mobile and that, similarly -- we're already on the hook for also Linux and Mac for that thanks to the Kickstarter. So it just keeps us honest about just supporting as much as we can all the time. Because who knows where everything's gonna be in two years?

You don't want to be backed into a corner, because that can be a real significant problem.

JPL: I think betting big on a single company seems like the worst idea. So that's another reason. It's another reason not to be a fanboy.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like