Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

An examination of the controversial underworld of the Japanese videogame industry

(I do not own the heading photo, it just seemed cool and yakuza related)

Between August 15 and 17th I was in Leipzig, Germany, for Replaying Japan 2016; a three day academic conference with multiple papers on Japanese games, and with four significant keynote speakers. It was fascinating, and there were some rather surprising revelations regarding Namco's history by three of the keynotes.

It's worth checking out the conference's program to see what else was on.

Below is an abridged version of my talk, related to the sometimes brutally difficult conditions in the Japanese game industry, and also the involvement of the yakuza. This especially interested me because so few people ever examine or discuss it. The only person who I can think of who has done anything significant in this field is Jake Adelstein. One of the post-talk questions related to the fact Japan now has very strict laws monitoring companies involved with yakuza, but as Adelstein points out in, some game developers are quite openly involved. Also, as was pointed out, the anime and manga industries have their own word for hamachi, the word I was told being kandzume (缶詰) or being "canned in" to finish work.

Several sections I have edited, censored, or removed entirely from what was shown at the talk. In the past three years I have won four court cases for false and unfounded allegations accusing me of libel. I don't like it, but crazy people are crazy, and if certain groups are going to interfere with the job of a journalist, then this is the situation we find ourselves in: unable to document the truth.

The talk was based on interviews from my trilogy of books on the Japanese games industry. Most of the images below are the slides used to illustrate my presentattion.

If anyone would like to commission me to write something based on my growing portfolio of work, my contact details are on my Gamasutra profile page.

Conference talk:

Since we're at this conference, we can probably all agree that Japanese games -- and their history -- are hugely important: they are technically accomplished, innovative, and provide distinct styles of enjoyment & originality. But this is not because of some kind of magic, as certain Western fans seem to think. It's because of hard work and sacrifice -- we seldom see the sometimes dark side of development. For this paper I will look at examples of the difficult work conditions developers faced, and then finish with something controversial -- yakuza involvement. Although you might be shocked to hear these stories, these events helped force the industry to grow very large very quickly, overtaking the Western markets of the time. These "dark" aspects are a part of the history of games, and should not be buried because they make us uncomfortable. Understanding how and why Japanese games became so successful, even if it involved exploitation or unsavoury elements, can provide a wider contextual understanding that could benefit future developers. Perhaps the reason Japan dominated American and European markets is because its talented workforce sacrificed so much to pursue creativity, while its managers were willing to bend the rules to protect their market interests.

In 2013 I spent three months living in Japan, interviewing over 80 game developers to produce three books: The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers. My intention was to understand the background to my favourite games - what I did not expect, what surprised me, was how challenging it was for the men and women who created these games. For many, their stories had never been heard, and they were keen to share the good times and the bad times they faced. It occurred to me we have very little understanding of how the Japanese industry worked. In fact, their stories mirrored what developers faced in the West, and there were more similarities than I realised. Crunch time is ubiquitous, implying a solidarity among developers the world over. Having said that, though tough conditions are common in game development, in Japan I heard accounts of worrying extremes. What I hope to demonstrate is that these are not just "products in boxes", people really suffered and sacrificed to bring us these games.

I heard personal accounts describing being locked in offices, underage staff, office raids by the police and regulatory agencies, physical violence, and stories of colleagues literally working themselves to death; intermixed with revelations of the yakuza protecting arcade operators from gangs and intimidating court witnesses in patent cases, of corporate bosses being arrested for tax fraud, and the political machinations that happened behind the scenes.

Much literature has been devoted to the characterisation of Japan as a culture emphasising hard work. Up until the 1980s, it was normal for schools and businesses to operate 6 days a week! There is even a word for death from overwork, karoshi -- high profile cases abound, such as Toyota engineer Kenichi Uchino, whose family received compensation for his death. Although videogames are a leisurely pursuit, the foundation and history of Japanese game development is built on long hours and tough conditions.

Tokihiro Naito, creator of Hydlide, explained the HAMACHI room at T&E Soft. In Japanese hamachi is a type of fish, but the name is a portmanteau of "crunch" (kaihatsu ni HAMAtta) and "people" (hitotaCHI), so hamachi or crunch room. According to Naito: "When you entered the room, the door was locked from the outside. Sometimes we'd throw a programmer in there, lock the door, and say, 'We'll let you out once you finish your coding!'"

Another story was by Yasuo Yoshikawa of T&E Soft, describing how on his first day of work he was left inside a dark apartment for over 6 hours, until he heard a strange creaking sound - someone asleep on the floor next to the desk got up and started working. Yoshikawa said: "I was nervous, so didn't say anything. Finally, the president came around. It was too late to go home so he said, 'Why don't you get some work done?' I ended up working all night. The next morning, when everyone started going back to sleep, I was told to go home."

It's important to consider the context of workplace hierarchy when hearing these anecdotes. If the boss stays late, then all the staff under him stay late. Some bosses were also incredibly strict. Even someone like Keiji Inafune had to fall in line with the demands of his superiors. Keiji Inafune described his boss at Capcom, who could be a bit of a tyrant: "My boss was incredibly hard to please and taught me the necessary strictness of game development. He'd do the checks for our content, but since he was so strict, even if the stuff was good he'd say, 'This is no good!' We really bore the brunt of his drive. If I was to treat my team now in the way I was treated back then, they would quit."

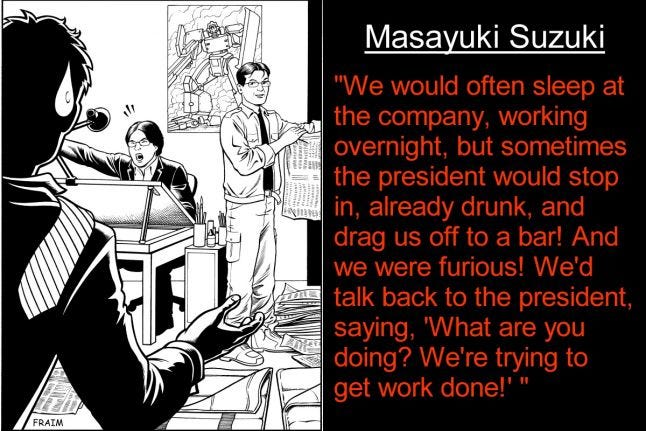

I soon realised most developers had a hamachi room - it was rare to create games without crunch time. Even when bosses - or senpai - tried to arrange relaxation time for employees, they would refuse and wanted to keep working! Masayuki Suzuki, of Masaya, described ignoring his boss' orders: "We would often sleep at the company, working overnight, but sometimes the president would stop in, already drunk, and drag us off to a bar! And we were furious! We'd talk back to the president, saying, 'What are you doing? We're trying to get work done!' "

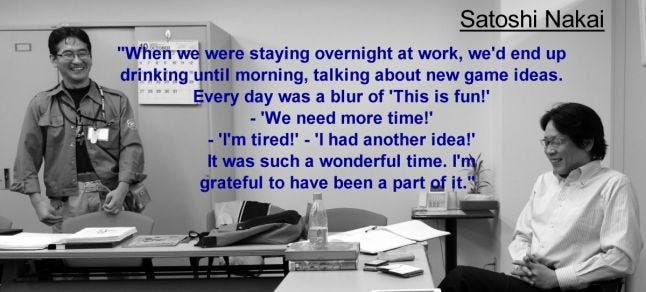

Despite these struggles, staff did it NOT because they were forced, but because they loved it. Satoshi Nakai, artist and designer on Valken, and colleague of Susuzki at Masaya, recalled the time fondly: "When we were staying overnight at work, we'd end up drinking until morning, talking about new game ideas. Every day was a blur of 'This is fun!' - 'We need more time!' - 'I'm tired!' - 'I had another idea!' It was such a wonderful time. I'm grateful to have been a part of it."

This was a common theme I found. Game developers were on the cutting edge of technology and creativity, and they endured the hardship because of the joy.

Long hours can of course also lead to health complications, even death. Yoshikawa of T&E said: "I never went home for six months, working and sleeping in the Hamachi room. One Sunday I went home, took a bath, and went to sleep. When I woke up I was blind. I was terrified and someone took me to the hospital because I couldn't see anything! The doctor said it was not a condition young people are supposed to get. So I was ordered to take rest from work."

Mikito Ichikawa, who started working at Falcom aged 14, also became ill and nearly died. He says: "I became very ill with collagen disease. The doctor said I had around a year and a half left. The cause was stress, basically. I started working from a very young age, and that took a heavy toll on my body. I'd regularly go for three or four days without sleeping. With the way I was living, I could have contracted any number of illnesses."

An even more startling revelation comes from Kensuke Takahashi of Zainsoft, who described talking with Kouichi Nakamura, the co-creator of Dragon Quest, on multiple occasions at industry events held by Nintendo: "Nakamura said it was not easy, and he was not as successful as he appeared. He said that at the worst times he had faced enormous debts, hundreds of millions of yen, enough to make him contemplate suicide. He had some severe ups and downs."

If the co-creator of such a high selling franchise contemplated suicide, it highlights how challenging things could be. Those of us here think we see success, but it's not always so. For me it's heartbreaking to learn how these young creators were exploited by managers and businessmen - and even the yakuza. That's the trouble with being a creative professional; if you don't care enough about the money you deserve, then someone else will surely take it.

I've already discussed the "hamachi room" - which is entirely different from isolation or quarantine rooms, in Japanese these are "kakuri-beya" or "oidashi-beya". They are a method by which Japanese firms encourage staff to resign rather than firing them. According to Asahi Shimbun, even large firms like Sony and Hitachi did it. (Asahi Shimbun has since tried to remove this news story, but Wayback still has it!) Googling brings up multiple sources attesting to such events.

One interviewee described how the problem came to a head in 2000. "Sega would put employees alone in a room and give them nothing to do, to make them resign. Former Sega employees sued and won, and were issued a public apology. They didn't just put people behind a partition, they sent them to a completely different floor. Sega didn't just lose a lawsuit over this, their image was completely tarnished. Nobody wanted to buy games from a company like that."

Despite the significance of this landmark court case, which happened around the time of Sega's near bankruptcy and cancellation of the Dreamcast, this event went almost entirely unreported in the West. I could only find one news story online, from IGN. Searching online for "Sega" and "kakuribeya" ( 隔離部屋 ) brings up Japanese articles - but why not any coverage in English? This was a clear abuse of staff, upheld by the courts.

Some of the most shocking revelations regarding workplace conditions came from Kensuke Takahashi, regarding life at Zainsoft. Takahashi said: "Recently in Japan people have started talking about 'black corporations', evil sweatshops that exploit employees. But Zainsoft was on a whole other level. I was punched and kicked regularly. One time, the CEO took a 14-inch CRT monitor and threw it at me. The CEO was a psychopath - once I kept working for nine days with little sleep, and he spotted me dozing off. He came up behind and kicked me as hard as he could. I was so tired the pain didn't even register. I hit my head against the monitor hard enough to make the screen crack."

As he describes it, Takahashi worked at Zainsoft for four years, on average for 20 hours a day, not going home for months at time, and seeing over 60 new staff join and then leave. The urban legend amidst consumers and magazines was that Zainsoft was run by yakuza. As it turns out, the CEO was not yakuza. He grew a moustache and acted tough to appear older, so people would take him seriously. Ultimately he was arrested for defrauding Apple.

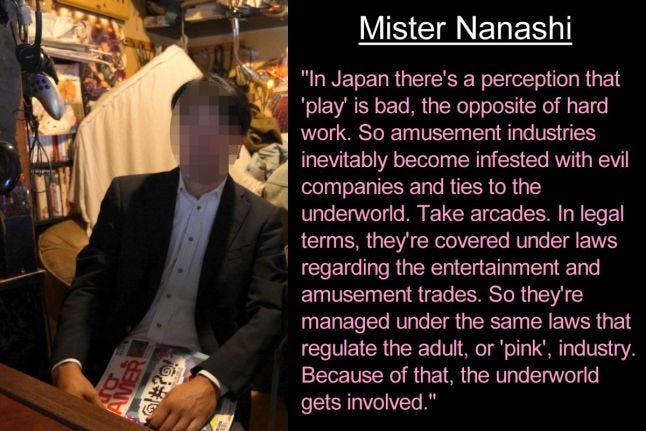

Although Zainsoft's CEO was not the organised criminal I expected, it leads to the topic of actual yakuza involvement. Few wanted to speak on record, but it seems many game companies were founded by yakuza. English literature on the history of Japanese games increases each year, but very little examines the yakuza, or how criminal elements protected and nurtured the growth of the industry, especially arcades -- brief mentions by Steven Kent and Tristan Donovan, plus Goldberg and Vendal in Atari, Inc. I think Japanese games are the best in the world, but not because of a "mystical aura" around them -- a close examination of certain developers reveals they survived market difficulties and could improve because of other factors.

At this point I want to introduce "Mister NANASHI" - an interviewee who wanted all discussion on this topic published anonymously. He explained: "In Japan there's a perception that 'play' is bad, the opposite of hard work. So amusement industries inevitably become infested with evil companies and ties to the underworld. Take arcades. In legal terms, they're covered under laws regarding the entertainment and amusement trades. So they're managed under the same laws that regulate the adult, or 'pink', industry. Because of that, the underworld gets involved."

He went on to explain how during the early days of the industry, because of the way Japanese society functioned the yakuza were essential to maintain order. "I did business with Toaplan. I asked them about their copy protection plans. The person in charge went quiet for a minute, and then said, 'Sometimes you have to fight fire with fire.' In other words, pay some yakuza to go stamp out the other yakuza making pirate copies. When you are in that situation Japanese society, including the police, won't do anything to help you unless you've already been harmed. Being in that kind of society, you need the underworld to protect yourself."

I want you to try to imagine a scenario. The early days of arcades. Perhaps someone comes in and opens the cabinet to examine the internals, or steal the coins. Now imagine that yakuza are running this arcade, and some of the "employees" catch this person and severely beat them. It's not a good thing, but how else would the operators defend themselves? As Nanashi says: "If stuff like that had never happened, the games industry would not have developed as much as it did."

Challenging companies which are involved with the yakuza can be dangerous though. Nanashi described how he was a witness in a patent trial against a certain arcade developer: "My younger sister was kidnapped. [REDACTED] hired some gangsters to do it. At the time, she had just graduated high school and was a university student. They did it to stop me testifying on behalf of Nintendo. As to how I got her back... I couldn't take them on directly. So I used a truck crane to pick up one of [REDACTED]'s newly released arcade cabinets and smashed it in front of their main offices. I told them, 'Next time, this is going to be one of you.' And after that, my sister came home."

NANASHI described one former company president - who I cannot name for legal reasons - explicitly as being yakuza: "Guys like him, members of the board of directors, were involved in the underworld. Buying and selling game machines was mixed up in that, because it that business attracts yakuza. Now they're involved in the pachinko industry. Members of the board would have short fingers, like yakuza who got their fingers cut off. Originally he was president of an arcade distribution company; back then, those in overseas imports and exports almost always had shady connections. Mostly the bosses behind Japanese slot machine makers are the South Korean mafia."

Roy Ozaki, formerly of Data East, TAD, and later Mitchell Corporation, explained how the yakuza functioned: "Yakuza usually use front companies. There's a couple of big ones that physically disappeared. My partner, Niida, was the youngest branch office manager at Data East in Osaka. He hates yakuza. When you're selling coin-op stuff, yakuza were always coming because people would buy their 'yakuza calendars'. Who the hell wants a yakuza calendar that costs 100,000 yen!" (£660 / $1k)

As Ozaki revealed, the calendars were like a protection fee - you buy the calendar and they don't hassle you. He went on: "So the yakuza came in, and Data East had 11 employees in Osaka. They were scared. Niida sat with these two in the office for 10 hours. He said, 'No! I am not going to buy this calendar!' For 10 hours he starred them down. Yakuza gave up and left. He's a legend for that. Most companies would just buy the calendar."

This explains how yakuza were directly involved in the Japanese arcade industry, but I wanted to know which companies were specifically run by yakuza. NANASHI filled in the gaps: "You know that [REDACTED] is a public company, right? When they went public the president wasn't there. I met the guy on an aeroplane once. The guy that started [REDACTED] couldn't go there because he was involved with - <whispers> - the yakuza! I can tell you which family and the related people, which companies got involved. One American company... This is big money stuff. They asked me to be their agent. You'd be surprised at how many companies are involved. This is very dangerous ground. All the videogame companies were funded by yakuza. Forget this story! It could topple the whole game industry in Japan. This might put your life in danger!"

And that is the extent of what I discovered on the relationship between organised crime and videogames in Japan. Before my trilogy books there were very few sources with inside information on Japanese games development, and I've seen very few stories on yakuza involvement. Jake Adelstein, author of Tokyo Vice, is the only one I can think of. Everyone is too afraid of being sued for libel or slander to discuss it. My hope is that as we move on, there will be more investigations into the videogame underworld. My take on this is that the Japanese industry would not have seen the same level of success without it.

/END TALK

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like