Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

EA strikes out in Ninth Circuit Court Appeal in the Keller right of publicity case. Here's an overview of the case, which I wrote about earlier this year.

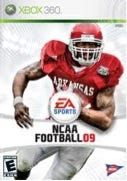

EA's NCAA Football

Right of Publicity in Video gamesEarlier this year I discussed Keller v. EA, a right of publicity case [1] that was appealed by EA to the Ninth Circuit Court, primarily on the basis of a First Amendment Right to use NCAA player likenessesin their college football games. The Ninth Circuit issued its opinion yesterday, holding against EA in what may prove to be a fatal and perhaps final blow in EA's self-proclaimed right to use sports figure likenesses in a game without express permission.

Keller proposes a fairly simple question: when can a real-person be included in a game without compensation? In answering it, two complex areas of law are addressed: an individual’s right of publicity and the First Amendment.

THE CONFLICT

In May 2009, former quarterback for Arizona State University and University of Nebraska, Sam Keller, filed a lawsuit against Electronic Arts, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA), and the Collegiate Licensing Company (CLC), the licensing arm of the NCAA, claiming that the use of his likeness, stats, jersey number, and position within Electronic Arts’ NCAA Football violated, among other things, his right of publicity.

In his class-action complaint, [2] Keller asserts that EA profited from his real life persona in its NCAA Football titles. EA did so without permission, and it violated Keller’s right of publicity in the process. [3] But the extent of EA’s infringement goes further. According to Keller, EA blatantly replicates virtually every Division I football and basketball player in their NCAA games, including players’ exact weight, height, statistics, body-type, home state, skin tone, hairstyles, and identifying accessories, such as wristbands and visors.

Keller believes the NCAA and CLC are complicit. Student athletes are not permitted to receive compensation for their skills, and NCAA bylaws prevent colleges from exploiting a student-athlete’s fame as well. [4] Yet, the NCAA and CLC granted EA exclusive rights that, in effect, enabled EA to exploit over 8,400 players, including those appearing in EA’s NCAA Football, NCAA Basketball and NCAA March Madness titles [5].

The NCAA denies that it granted EA rights to student-athlete images, but instead only licensed stadiums, team names, and identifying trademarks. As proof, they point out that, by default, student-athlete names do not appear on team jerseys in any of EA’s games. Keller agrees, but asserts that EA intentionally designs its sports games to allow gamers to circumvent this formality, providing a means to easily upload entire rosters of actual player names, after which player jerseys contain both the player’s number and name. Although EA could easily block this feature (as they do for profanity), they choose not to.

In February 2010, the Keller court denied EA’s motion to dismiss, based on, among other defenses, the First Amendment. The case is now on appeal to the Ninth Circuit.

Understanding Keller

In Keller, EA argued that if a work contains “transformative elements” not primarily derived from a celebrity’s fame, then the work is protected under the First Amendment. [6] EA proposed that if Mr. Keller and the other student-athletes’ likenesses were simply some of the raw materials from which their game was created, but not the very sum and substance of the game itself, then the game is protected under the First Amendment. [7]

The lower Keller court agreed with the transformativeness test but disagreed with EA's outcome, citing three examples:

Example #1 - Comedy III

In Comedy III Productions v. Saderup [8], artist Gary Saderup produced and sold a charcoal drawing of the Three Stooges in lithograph prints and T-shirts. Comedy III is the registered owner of the Three Stooges intellectual property rights, and sued Saderup under California Civil Code Section 990. The California Supreme Court applied the transformativeness test and determined that Saderup’s work did, in fact, infringe on Comedy III’s rights. In doing so the court made the following observation:

“The central purpose of the inquiry.…is to see whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is transformative.” [9]

Applying this to Saderup’s work, the court held it was not sufficiently transformative:

“Turning to Saderup's work, we can discern no significant transformative or creative contribution. His undeniable skill is manifestly subordinated to the overall goal of creating literal, conventional depictions of The Three Stooges so as to exploit their fame. Indeed, were we to decide that Saderup's depictions were protected by the First Amendment, we cannot perceive how the right of publicity would remain a viable right other than in cases of falsified celebrity endorsements.” [10]

Example #2 - Winter

Winter v. DC Comics involves the iconic rock and roll musician brothers Johnny and Edgar Winter, who sued DC Comics, alleging that DC had misappropriated their names and personas after two characters appeared in a five-volume miniseries, titled Jonah Hex. [11] The characters in question were giant worm-like singing cowboys named the “Autumn Brothers”, who, like the Winter brothers, were albinos, and drawn with similar long white hair and comparable clothing.

Using the same transformativeness test as in Comedy III [12], the Winter court held that the Autumn Brothers were sufficiently transformative:

Application of the test to this case is not difficult…. Although the fictional characters Johnny and Edgar Autumn are less-than-subtle evocations of Johnny and Edgar Winter, the books do not depict plaintiffs literally. Instead, plaintiffs are merely part of the raw materials from which the comic books were synthesized. [13]

Example #3: - Kirby

Kirby v. Sega of America involves the leader of a retro-funk-dance musical group known as Deee-Lite, which made several music albums in the 1990s but was best know for a single hit, Groove Is in the Heart. Kierin Kirby, Deee-Lite’s lead singer provided the group a provocative persona, including a unique look incorporating platform shoes, knee socks, cropped tops, pig-tails, and a signature lyrical expression “ooh la la.” [14] Kirby refused when Sega of Japan approached her to license Grove for one of their games.

After Deee-Lite disbanded, Sega of Japan created a game (distributed in the U.S. by Sega of America) called Space Channel 5, incorporating a character with attributes similar to Kirby’s Deee-Lite persona. The game’s creator, Takashi Yuda, testified that when he created the Kirby-like character, he named her “Ulala,” similar to Kirby’s own signature expression.

In 2003, Kirby sued Sega, claiming common law infringement of the right of publicity, misappropriation of likeness, violation of the Lanham Act, and other claims. Sega sought protection under the First Amendment.

Applying Comedy III and Winter, the Kirby court held that Sega’s Space Channel 9 contained sufficient expressive content to constitute a transformative work. While Ulala was similar to Kirby, the game’s character was a space-age reporter and unlike any public depiction of Kirby. [15]

The Keller Court Reasoning

Applying Comedy III, Winter, and Kirby to the Keller facts, the Northern District Court in California held that EA’s NCAA Football was not sufficiently transformative so as to bar Keller’s publicity claims as a matter of law.

The court pointed out that, like Keller himself, his virtual NCAA Football equivalent plays for Arizona State University, shares many of Keller’s physical characteristics, including his jersey number, height, weight, and wears the same accessories as Keller did while playing football. TheKeller court concluded that:

“EA does not depict Plaintiff in a different form: he (Keller) is represented as he was: the starting quarterback for Arizona State University. Further, unlike Kirby, the game’s setting is identical to where the public found the Plaintiff during his collegiate career: on a football field.”

EA, in their appeal, argued otherwise. They purported that their NCAA games do contain transformative elements, including unique stadiums, sounds, commentary, and fictional scenarios unlike any real-world experience. EA believes that the Keller court mistakenly focused only on the work’s main characters (as was done in Kirby and Winter), when the work should have been considered as a whole. EA also argues that the court was in error by not applying the Rogers test (which is briefly discussed below). [16]

Another Perspective: Hart v. Electronic Arts

In October 2009, in a case with strikingly similar facts, former Rutgers University quarterback Ryan Hart sued Electronic Arts in New Jersey District Court for essentially the same complaint as in Keller: right of publicity. [17] [18]

But the New Jersey court ruled opposite of Keller. In September 2011, U.S. District Judge Freda Wolfson granted EA’s summary judgment motion, holding that EA’s First Amendment right outweighed Hart’s right of publicity under…you guessed it…the transformativeness test.

Judge Wolfson held in a 67-page opinion that the balance was in favor of Electronic Arts. She cited many of the same cases as in Keller (Comedy III, Winter, and Kirby), but ruled that EA’s virtual stadiums, crowd sounds, commentary, and other interactive features provided transformative elements sufficient for First Amendment protection.

However, Hart appealed to the Third Circuit and the lower court opinion was reversed in his favor. Earlier this month, EA requested a full Appeals Court review (rather than a three-judge panel), and the court refused, leaving EA with limited options.

Ninth Circuit Decision

With the Ninth Circuit's recent 2-1 decision, holding against EA's First Amendment argument in Keller as well, Electronic Arts is further boxed in. No doubt they will appeal to the United States Supreme Court, but there is no guarantee that the Supreme Court will hear the case. In that event, the Ninth's decision will hold in cases with similar facts and circumstances.

By Dan Lee Rogers (c) 2013

Please tweet or like if you enjoyed or found this article useful.

///

1. California’s right of publicity law provides for damages up to $1000 per likeness per platform, plus treble damages if the use was willful or intentional. See http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/news/2011-08-02-ncaa-lawsuit-electronic-arts_n.htm for a discussion of the damages of this suit.

2. http://www.courthousenews.com/2009/05/06/ElectronicArts.pdf

3. Keller claims EA violated its right of publicity under California Civil Code §3344, which states: Any person who knowingly uses another's name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness, in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services, without such person's prior consent, or, in the case of a minor, the prior consent of his parent or legal guardian, shall be liable for any damages sustained by the person or persons injured as a result thereof.

4. NCAA Division I Manual 2008 states, in part, that a student athlete’s amateur status is lost if the student athlete uses his/her athletics skill for pay or signs a contract or commitment of any kind to play professional sports (12.1.2). However, a member institution may use student athlete’s name, picture, or appearance to support charitable, educational, and activities incidental to participation provided such use is to support the charity or educational activities considered incidental to the student athlete’s participation in intercollegiate athletics. (12.5.1): http://www.maine.edu/pdf/NCAADivision1RulesandBylaws.pdf

5. See http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/news/2011-08-02-ncaa-lawsuit-electronic-arts_n.htm

6. EA had further argued that transformativeness is not the only test that should be applied. Rather, in looking at both the public interest and a test borrowed from trademark law, called the Rogers test, EA claimed that Keller’s claim suit was without merit. Nevertheless, the Keller court chose not to use the Rogers test, and it discounted EA’s public interest argument as well, focusing instead on transformativeness.

7. Winter v. DC Comics, 30 Cal. 4th 881, 885

8. Comedy III Productions, Inc. v. Gary Saderup, Inc., 25 Cal. 4th 387, 409 (Cal. 2001)

9. Id., at 808.

10. Id at 811.

11. Winter supra.

12. The transformativeness test used in Comedy III is as follows: “The test to determine whether a work merely appropriates a celebrity's economic value, and thus is not entitled to protection the First Amendment, or has been transformed into a creative product that the First Amendment protects, is whether the celebrity likeness is one of the ray materials from which an original work is synthesized, or whether the depiction or imitation of the celebrity is the very sum and substance of the work in question. The court asks whether a product containing a celebrity's likeness is so transformed that it has become primarily the defendant's own expression rather than the celebrity's likeness.”

13. Id., at 479.

14. Kirby v. Sega of America, Inc., 144 Cal. App. 4th 47 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 2006)

15. Id at 59.

16. The Rogers test resulted from Rogers v. Gramaldi, and has been applied to a number of right of publicity claims. That test, in essence, asks: whether the challenged work is wholly unrelated to the underlying work, or whether the use of the plaintiff’s name and/or likeness is simply a disguised commercial advertisement. The Rogers test history lies in trademark infringement (thus the language here), whereas the Transformative test is rooted in copyright law.

17. Moved to Federal Court from the Superior Court of New Jersey on November 24, 2009.

18. See United States District Court of New Jersey Opinion: http://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-jersey/njdce/3:2009cv05990/235077/23/0.pdf?1285240988

19. Rogers v. Gramaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989)

20. Hart, 808 F.Supp.2d at 783-786

21. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/16/sports/16videogame.html?_r=0

22. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/04/sports/04ncaa.html?_r=0

23. http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Alien.html

24. The first Bill of Rights was ratified as Constitutional Amendments on December 15, 1791.

25. Roberta Rosenthal Kwall, Fame, 73 IND. L.J. 1 (1997), as discussed in Southern California Law Review: The Right of Publicity Vs. The First Amendment: Will One test Ever Capture the Starring Role: http://weblaw.usc.edu/why/students/orgs/lawreview/documents/Franke_Gloria_79_4.pdf

26. Id. For a great discussion on this topic, see Southern California Law Review: THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY VS. THE FIRST AMENDMENT: WILL ONE TEST EVER CAPTURE THE STARRING ROLE?:

27. Pavesich v. New Eng. Life Ins. Co., 50 S.E. 68, 74 (Ga. 1905).

28. See: Marquette University Law School: Baseball cards and the Birth of the Right of Publicity http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1156&context=facpub; also see Haelan Labs., Inc. v. Topps Chewing Gum, Inc., 202 F.2d 866 (2d Cir. 1953).

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like