Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In an extremely wide-ranging interview on the state of the art, Gamasutra steps back and chats to Silicon Knights' Denis Dyack (Eternal Darkness, Too Human) about the big themes of game development, interactive story, and exactly what our industry should and shouldn't be taking from Hollywood

Earlier this month at Austin GDC, Denis Dyack took a short break from breakneck development on Silicon Knights' latest epic Too Human to deliver a presentation in the writing track on 'Engagement Theory'. Defined by Dyack as "engagement is greater than, or equal to, story plus art, plus gameplay, plus technology, plus audio," the theory is a way at looking at game development in a "big picture" sense.

Shortly after the speech, Gamasutra and Game Developer's Brandon Sheffield was able to corner Dyack and talk, in an extremely wide-ranging conversation, about the big themes kicking around the conference floor -- and his unique perspectives on game development, story, and what our industry should and shouldn't be taking from Hollywood.

You were saying that there was no formula for making games, which is certainly true, but among others, Raph Koster has been breaking down grammar of games. It's kind of like structuralists and post-structuralists did with movies -- just breaking it down into base elements and segments of what games are. So, doing that, and then figuring out why things like MySpace and Club Penguin are kicking games' ass in terms of revenue and stuff...

It was really kind of an interesting thing, because the way he was talking about it, he's at the complete opposite end of the spectrum, where you give users this ability to create things, and you give them the ability to put themselves in. Not like in a virtual world, but they have a profile, and people know who they are, and that sort of thing. It's like anti-story, in a way. He freely admits that the stuff that's most viewed on those kind of websites is almost invariably the crappiest. The worst stuff is the most exciting to a lot of people.

Denis Dyack: I think breaking that stuff down definitely has its value, and in some ways -- the engagement theory that I talked about -- I tried to come up with a universal system where we can categorize some metrics and at least say, "Here's a direction to go in," but at the same time there's a school of thought in psychology that everything is story, and there's story in everything in our lives.

My identity is my story, and me telling you my story and how I feel. Your story in RTSes is real-time, and the story there is when you beat your friend and took over his base, or how you beat him in two minutes. I think with these kinds of creations, if you give people the tools, the stories are there. They're just being told in different ways.

Right. They're being told by the user, rather than by the game designer, director, or storywriter, which is very different. It doesn't allow the creators of the game to be the auteurs.

DD: That's a real interesting setup. I don't know if that's a bad idea or not. If you look at Norse mythology, as an example of a story, I would imagine that there was no singular author. In a sense, if the Norse mythologies were the religion of the time to justify living conditions and why people died and how society should be run, maybe these stories were generated the same way that this is. Maybe this is just as fine. I think it certainly has potential value.

It could be actually creating a new mythology.

DD: Maybe that's what it is. Maybe that's how the mythologies were born.

Technology mythology.

DD: Yeah.

It's entirely possible.

DD: It's an interesting thing, and I think it certainly has a lot of potential. I understand technology pretty intimately -- at least I think I do -- and a lot of fear of technology and what we're doing with it people feel that they're -- and you can be -- devalued. You've got to watch out for commodification, and make sure that humans aren't commoditized. But at the same time, if you understand the technology and understand how you can contribute to that and you can do it in a positive way, you shouldn't worry about whether there's a director or not or whether we have to tell the stories.

I don't know if that's necessary. I think that's why I do, and I enjoy doing it. I know that that's never probably going to replace the Silicon Knights games, so I'm okay with it. I think it might be really cool. I haven't tried it. I want to try it now. Now you've got me interested in it.

The way he was talking -- and he's very right about this -- was that games are always going to be a niche. Games, as we create them now, are not going to be as mass-market as something like YouTube can meet.

DD: I don't know about that.

As we're creating them right now.

DD: Oh, okay. Sure, sure.

He's saying that games can expand, and that's what he's trying to do, certainly. But the way we're creating games right now where it's a singular experience in some ways, even in like World of Warcraft. He showed a screenshot of it, with all the boxes and stats and things, and I look at that, and I've never played World of Warcraft, and I have no idea what could possibly be going on or what you can even do. It's interesting in a way, because you want to be able to create something that is of traditional value, in the manner of Lord of the Rings, as something that will live on in peoples' memories as this amazing, singular experience that a whole bunch of people have a similar feeling about this one experience. But all this other stuff is going in that other direction.

DD: I think it is, and I think there's room for it. I think it's great.

My big worry is that if that sort of thing takes off, the niche games such as they are -- which I enjoy -- would be of less value to society at large. But in some ways they would probably wind up being of greater value, because the focus would not be on them as a vehicle to advance the world.

DD: One of the things you keep in mind about technology is that it's accelerating, but so is our ability to learn the technology. There's some stuff on id.com that I referenced in my last time, but there's studies and research that shows that people are catching on faster -- logarithmically, as well. The time it took for people to understand the Internet was ten times faster than it took them to understand typewriters. We're catching on too, so that when he says that he looks at World of Warcraft and this particular speaker says he doesn't understand the stats...

It's me who doesn't understand the stats.

DD: Oh, okay, I'm sorry. That shouldn't be intimidating, because once you play, you'll get it. Our children beyond this will learn that ten times faster, and who knows how it's going to go. From that perspective, I don't think that's a worry. Complexity itself is really going to find the medium where we can adapt and utilize it.

Right. Certainly it's something that people can adapt to, but the fact that it's a barrier toward wanting to... because you look at this thing, and it's like a wall. Everybody's been saying, "How do you get moms to play games when they can't figure out what any of the buttons do?" They just don't know, because they've never done it before. It seems to them like something that's completely beyond them and is going to stay that way.

DD: This really plays into my thoughts on Wii in many ways. If you look at the Wii -- which is really doing super well, and people are picking it up -- the question is not the adaptability of people moving towards that. It's not in question. It's very popular. It's very cool, and very hip. The real question is, "What's going to happen after two to three years from now?" when people look at the technology. People do learn.

They're going to adapt, and they're going to want something beyond Wii Sports. There's going to be some party games, but after awhile, as their sophistication grows, the real question with the Wii is, "Will that platform be able to compete against the more sophisticated technologies, like the PS3 and the 360?" Out of the gate, I think the Wii is doing a great job of introducing people. The real question with the Wii is whether it will hold on to those people until the end of the generation.

Is the Wii's popularity sustainable?

My guess for that was that the Wii would continue as it is, but Nintendo would see to it themselves to release the next level of console to those people, so that people who are like, "Well Xbox and Sony are still these weird things that I can't deal with... I remember that I like that Nintendo Wii!" That's my guess.

DD: You think so?

That's my guess. With the Wii, they're selling it at a profit out the gate. They don't need to have a five-year console cycle. They can release another console soon, and it's not the exact same thing, because as long as they could support two...

DD: Yeah, there's no question of being successful. The tricky thing about technology is that it's so unknown. Trying to predict who is going to win the console war right now is probably the hardest thing ever. If you go talk to a publisher about what horses they're backing, you'll maybe get a different answer every hour from the same publisher because things change so rapidly. It's really hard to call right now.

People are definitely hedging their bets.

One thing that you mentioned earlier was about scriptwriters and the human element of film creation that can be commoditized. I have a slight problem believing that's true, because while there is certainly people that you seek out and try to attach to a film or something like that, but at the same time, they are then allowed to lend their personal creative vision to that, and are given power within that. It's empowering as well.

DD: I guess if you look at my opinion -- and my understanding of the film industry -- the fact that everyone's contract and no one has a permanent job, that's not... some people do well in that. There's certainly some directors who became very successful. But I'd say the majority of the people in that industry do not like that model.

Interesting. My perspective is that the majority of people in this industry don't like the model that we use, because you've got a group of people always together, and there's like a "boy's club" insular mentality in certain ways. It's like once you're in the industry, you don't get booted out of it. You have to do really super bad to get kicked out of this industry.

DD: We're not big proponents of recruiting within the industry. We generally don't even look at it. Industry experience can be an asset, but it's necessarily an asset. However, if you look at Nintendo, those guys have been working together for 25 or 30 years. It seems to work for them.

Some people have made the point that I could make a great game with Ken Levine from BioShock and Cliffy B and Warren Spector. If I put those guys together, they would make this awesome game.

DD: Mm.

I know, I'm just saying.

DD: Yeah, I don't think they would, but I don't know.

No, I don't think they would either. I think they would just make something really terrible and then split up. But anyway, why shouldn't you be able to get the right talent for the right job?

DD: Oh, you should. I think from the perspective of a business model, it would be great if you didn't have to carry staff and look after them, and if you could just bring people on when you needed them and let them go when you didn't. I think for the talent itself, though, that's a commoditization. You become a utility, and your value becomes diminished significantly. At Silicon Knights, we don't hire part-time people. We don't outsource. It's all to protect the talent, which we are. I look at these models in Hollywood, and I think it's kind of broken in many ways. There's a lot of people who are struggling.

I think Hollywood has some really good things about it. There's a lot of things to learn, but there's a lot of things that you want to avoid as well. That's one of them: the commoditization of talent. One of the ultimate commoditizations of a human being is slavery. You can get even further than that, and you don't want to go there. It's whatever we can do to watch out for that. When I saw this, I referenced it in the scripts. I saw the screenplays, and I was like, "This is really homogeneous. They've got all this rules about interior, exterior, outdoor, light time, and night time."

I thought at first it was really terrible, but then after reading about 25 of them, I'm like, "Okay, I get it. I get now that after they submit this the director changes it. He puts it where he wants it." But what that does is say to the writer, "Okay, you're valuable, but you're not that valuable." It puts trust with everyone in their place. But that's my opinion of it. Maybe it's being sort of ignorant, I don't know.

Silcon Knights' upcoming mythological action title Too Human

That's sort of the opposite perspective that some people have. When you take a specific person, you could consider that you're giving them value, because you're saying, "I need you to do this, because you are the one who can do this for me." Some other people would find that floating around from project to project gives you a lot of freedom, and gives you the ability to work on different things instead of being like, "I have to do this one thing. I have to make textures in four years this exact way."

DD: That's a commoditization, too.

Yeah. There's certainly both sides on either way there.

DD: When you think about commoditization in technology, there's really... this is a reference from Ursula Franklin in The Real World of Technology -- she describes methodologies in two ways. One is prescriptive -- that's where you have a process where you say, "Okay, we're going to do this, this, this, and this." It works really well for people who don't know what they're doing and they're learning it for the first time. A prescriptive model has very hard set rules. Prescriptive models were used during the industrial age, for manufacturing. The other approach is the holistic model. The holistic model is learning from peoples' experience where they have knowledge and understanding, and they have a set of rules, but they use their experience to overcome unforseen circumstances, and they adapt well. The holistic models are generally, in my opinion, much better.

From a perspective of making sure that the talent behind what's being created really has an opportunity to get their own creativity in there, and they can use their experience to overcome challenges, whereas with the prescriptive model, it would be like, "I can't do that. It's a rule," whatever that may be, whatever that rule is. In those different ways of doing things, the prescriptive model is unfortunately becoming very dominant in society. People automatically want rules, and they automatically fall into... it's just like when technology is introduced. [It] suddenly becomes this awesome thing that's going to change your life for the better. This is back into the technology talk, but when I talked about commoditization of technology, when the sewing machine was introduced, it was introduced and marketed as something that was going to free women from sewing.

It was going to change their lives so that they could sew five minutes a day, and do more sewing than they could otherwise. After awhile, they became mass-marketed and commoditized, and then someone figured out, "Hey, I can make these sweatshops where people can be sewing all the time," and suddenly, this really good thing became this really bad thing. Technology is always that way. In the film industry, I do see that as a negative, and I really wish we could, when we look at all these things... we can't always ask -- and I think that's one of the central themes in Too Human -- just because you can doesn't mean you should. Every time we figure out we can something, should we do it?

If we're going to start splicing our genes and decide whether we have males or females, or whether our son is going to be blonde or brunette, or if he's going to be very muscular or intelligent -- should we do that? Is that the right thing? What is that going to do 100,000 years from now, when our genetic code is completely controlled by us? Is there something in the random generation of DNA that helps us survive? Are we going to be extinct? We need to think about these things. These are the kinds of things with technology that I think that we have. That's why I brought that up. It wasn't necessarily to make the point that it's bad, but I think there's definitely some bad things in Hollywood that we need to avoid.

That's actually the same thing that they're tackling in BioShock. Rather transparently, but it's the same deal.

DD: Yeah. That's a good game so far -- I'm about halfway through.

To the rules point, one could argue that there are too few rules in game development. We don't have a best practices bible that all the people in the craft have figured out. "Yeah, I see what you're doing and I've made this screw-up before." When we run post-mortems in Game Developer magazine, the "what went wrong" section is carbon copy, almost every time. It's like, "We didn't plan it well enough. We were reluctant to cut certain features. We had to crunch too much. The publisher wasn't responsive enough at certain times, or we weren't responsive enough." It's the same old stuff, and it seems like as good as we sometimes do with conferences like this and sharing of information, we still are all repeating each others' mistakes without even realizing it.

DD: I think that's true. When I did the talk in 1996, the point was that we don't have an Aristotle's Poetics for the gaming industry, and that's when I tried to create that universal theorem -- the engagement theory -- that would try to help. So I agree with that. But the other thing, unfortunately, is there's no metrics so far for what makes a game fun. No one can define that.

We're trying to be proactive at SK. What we're doing actually with the local universities is we started something called the Interactive Arts & Sciences. We're working with Brock University in creating a program where it takes the arts and sciences together to help create disciplines of gameplay ludology and other things. So people are coming up with a very strong foundation for the future, so we can actually create some of these metrics and standard principles -- not necessarily rules -- for which we can base our things on.

So kind of like video game critical studies?

DD: Yeah, it's a video game degree. Rather than call it "video game"..."interactive media."

It feels like we, as an industry, don't have the time to step back and really think about it, because we're always pushing forward to finish the thing that we're working on. It's really hard to take a larger view.

It feels like we, as an industry, don't have the time to step back and really think about it, because we're always pushing forward to finish the thing that we're working on. It's really hard to take a larger view.

DD: Research and development in our industry is almost nonexistent because of crunch time. Whenever I hear about someone trying to create the world's greatest AI, it's all marketing. It's never real. I didn't talk about this in the talk, but our second game, Fantasy Empires had a learning neural network and an agent that would try to learn from what you were doing. It was part of my master's thesis. We did a lot of tests on it. It actually adapted, it helped people, and it actually was a great test case. We put it in Fantasy Empires, and it was a little bullet point on the back for marketing and no one noticed. No one cared.

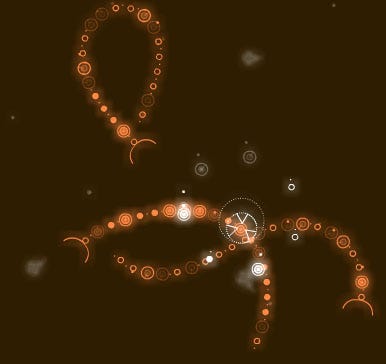

It's all about the entertainment value, and I strongly believe in that too. It's disappointing sometimes. It's really interesting to see the one talk -- the one before mine -- where the guy started talking about flOw. He's like, "Someone beat me to it!" And I'm like, "Man, flOw's been around for 25 years." That's what I was talking about -- nobody's talking to each other. He brings up a game, and just because it's called flOw, it's like people have been talking about flOw in our industry for... I remember I did a talk on it in 1996, so that's 11 years ago. And that was at GDC, after Legacy of Kain.

The fact that we have these people that are speaking in the industry who don't necessarily know the stuff -- that's one of the problems. We have to communicate more, and we have to try to get out there. I like these conferences for that, and I did like that he tried to put forth theories on stuff, even if it's not necessarily everything I believe in, but we've really got to get away from. So the things that I'm worried about at GDC is, "How awesome is your game?" "Oh, it's so awesome, and here's my new gameplay demonstration and what we're going to do." To me, the marketing is winning out over the industry development.

It's all about Blast Processing.

DD: Yeah, exactly.

Actually, a friend of mine knows the guy who invented that.

DD: Blast Processing, from Sega?

Yeah. I really wanted to interview that guy, but he doesn't want to be known. He's afraid people will villainize him.

DD: I wouldn't. People are too worried about negative press. Negative press needs to be avoided, but at the end of the day, Silicon Knights is really going to prove the point that any press is good press, because we certainly have a lot of it.

Well, you have to realize that many of these people who are judging you do not have any degrees in what they're doing. They don't have any training. They have basic English ability. They really don't have any critical thinking training or skill, and it's basically like the Armageddon crowd telling you whether your game is cool, but that is the crowd that you have to make a game for.

DD: I'm totally fine with that, once the game's out. I look at the Love Boat Story -- I call it The Love Boat, but it's really Titanic. That movie was so criticized before it came out, and when it came out, it totally redeemed itself. That's where I think and hope we're going to be. But the one thing that I wanted to mention about marketing that I think is really true is this one thing Don Daglow said at Leipzig in his talk. I liked his talk, but the thing that really stuck with me -- and he later abandoned it -- but his definition of a next-gen game was how much marketing money was put behind it. I think it's totally true, because what does "next-gen" mean anymore?

Another thing that I wanted to talk about was the film/game crossover. A lot of people do talk about it, and hire scriptwriters and things like that. But it seems like we have the capacity in games for our own type of language, and our own way of perceiving things, to the degree that we really don't need them.

DD: I don't think we do. I think we can certainly learn. We've hired screenwriters at Silicon Knights, but they have to learn how to write for games, which is a totally different medium. If someone says, "I'm going to hire a scriptwriter to help with your game," my response is, "We already have them, and they'll do a better job because they understand the medium." Understanding the medium is key. Can screenwriters learn a new craft and work on video games? Absolutely, and talent is talent. But people who just write scripts for movies are not going to know how to write for video games, that's for sure.

It does seem, to the contrary point of what I was saying, that people don't pay enough attention to the other industries and what they can learn from them. The extent that it often goes to is, "Well, we need a triple-A story, so we're going to hire any random Hollywood hack we can find who's slumming in the game industry."

DD: It's funny. I often get caught in these debates. I'm a big proponent of learning from other mediums, and at the same time, I think I've tried to say that we're not the same, but people interpret that as, "Denis wants to make interactive movies," and people really attack that. What I've tried to say many times is that there's a lot different. We're interactive. They're not. Linear, non-linear: huge differences.

But the things that are similar, the historical trends we can look at and say, "This is what happened there. Maybe it's going to happen here or we'll follow a similar trend." That's where the gold is. The gold and all the nuggets are, "What can we learn, and what can these guys contribute to our industry?" I would love to see the industries merge, and for them to write both linear and non-linear is a totally different thing altogether. If people become versed in those kinds of tools, I think that would be fantastic.

There's a lot of interesting stuff with the fact that maybe we're just about getting out of it, but we're still in that first era of filmmaking. The first films ever screened were of a train pulling into a station, and people ran screaming from the theaters because they thought it was a real train, even though it wasn't real. After that, it was like, "What was the most shocking thing you can do?" like electrocuting an elephant or something like that. And we're still in there. It's in the graphics and the spectacle, and it's got to be big and loud.

DD: I totally agree. I think we're starting to get out of there. Cinema used to be called the cinema of attraction. People would go into movies, and there wasn't even a beginning and an end -- it would just sit there and play, and people would just go in. There's early films of firefighters rescuing people from burning buildings. I think we're getting to the point now where... I was talking to someone earlier today, and they were talking about reviewing video games. I think he was in the press, and he was like, "I love this game. It was fantastic."

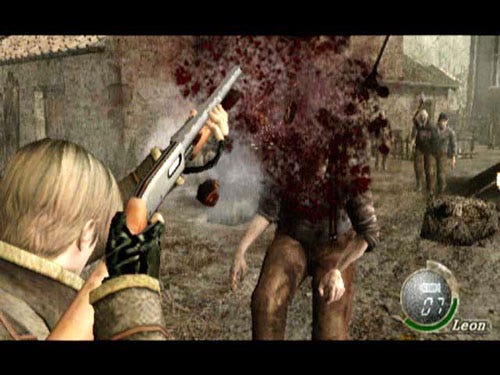

We were talking about the new Resident Evil -- Resident Evil 4. He was like, "The story sucked, and I just thought I had to take a point away because the story was bad. I got hammered for it, and everybody was like, 'This game is awesome, blah blah blah,'" Take engagement theory -- one foundation, that would be a great way to rate games. How's the content? Is the story good? Give that a number. How's the art? Is that good? How's the gameplay? Is that good? How's the technology? How's the audio? You take all those things and rate things, because when you start getting...

Well, that's what they do, but it's almost kind of a false thing, because it's arbitrary and subjective. It's like, "Compared to what? Compared to whose feelings?" It's pretty rough.

DD: But very few people take story and content and look at it, right?

It's true, but speaking of "the media is the message." Resident Evil 4 is my favorite game since 2000.

DD: Well, I guess that's last-generation now. That was a great game. The story wasn't very strong.

Capcom's Resident Evil 4 -- short on story?

The story wasn't very strong at all, but I didn't care. And I love story. I'm a writer, and it's a thing that I care very deeply about, but...

DD: I think that illustrates the point of the medium being the message, and the medium overpowered the message or the story, or they didn't focus on it. Maybe their messages are in the way that the game played.

It's true, but how much better could it have been with a strong story?

DD: Oh, can you imagine that with a strong story? And that's why I still really like engagement theory, because I haven't found anything that really throws it out and says, "That breaks it." Resident Evil was able to overpower it. Can you imagine how much better that game would be? Say that the pinky was the story -- that one thing, if they had made an awesome story on top of the graphics and the gameplay, it just would've been fantastic.

I think that's always the aim. I think people are always trying to do it, but they just can't.

DD: Trying to make an awesome story, you mean?

Well, no, trying to make every element of their game as good as can be, but they just can't do it, because they don't have the skill or the knowledge. I think right now as an industry -- to make a film analogy -- we're at the D.W. Griffith phase, where we're learning editing -- rudimentary editing -- but we're not dealing with subjects in the best ways that we could.

DD: I agree. I think we're trying, and I think that the camera system that I talked about and doing these basic things... the interesting thing is, they've developed this whole language of film that we can use now, but we have to learn to adopt it in non-linear ways. It's very interesting to see. And then we've got everyone coming at other things like psychological experiments on flOw. The breakdown of flOw that I saw today wasn't the one I would've chosen, but it was certainly interesting. You've got all these information things coming in, and I think the difference between the film industry and our industry is that the change is going to be much more rapid. When we hit something, it's going to go "Boom!"

Experimental indie game fl0w

We're having a hard time ramping up right now, though. One of the reasons is because we don't have someone like Thomas Edison to break all the other projectors so that we can just have one unified format.

Perhaps in 2007, the artistic implements or the techniques are crude, but we also have the same sort of focus grouping and audience-intent marketing stuff Hollywood has. At the same time, they're sort of at odds. What I'm saying is that the marketing people at Publisher X want to target the 18 to 34-year-old male...

DD: I don't know if that's true anymore. I have never met a publisher now that doesn't want to hit every person possible. I know developers who want to create true games to the art, and they don't care what rating they get, but I know publishers out there who... pretty much if it's not mainstream, nobody wants to do it anymore.

But look at a game like -- and this is totally a random example -- Turok. The new one. You're a marine and you're shooting dinosaurs. That doesn't hit everyone. It doesn't even come close. It's an adolescent power fantasy.

DD: I think people who look at a Spielberg movie -- all the Jurassic Parks -- would argue, "That's a Jurassic Park movie." They don't look at... if they feel that the game is going to have broad appeal, they'll do it. I'm not disagreeing that everyone's going to like a dinosaur shooting game, but certainly dinosaurs are pretty appealing.

Oh yeah, but Turok is all about gory finishing moves spraying blood everywhere.

DD: That's a creative decision, though.

But that limits the audience, too.

DD: Oh, for sure. There's no question. Manhunt's a great example.

Yeah, that was the one I was going for with the D.W. Griffith thing. We've got the tools there, but what are we using it for? Birth of a Nation was groundbreaking in terms of filmmaking, but in terms of the subjects it dealt with, it was very racially ignorant. With Manhunt, it's pretty amazing that you can garrote people with the Wiimote and stuff, but it's not a very socially responsible kind of thing.

DD: And people need to think about that stuff more, I think.

Certainly. I was wondering with the interactive camera stuff, have you played the Silent Hill games much?

DD: Mmhmm.

I think the way they do it -- where they have these fixed cameras that they want you to see, but if it becomes extremely difficult to see the action around you, you can set the camera behind you -- the angles they create are so compelling that you kind of want to leave them there, because it draws you in.

DD: In Eternal Darkness, we had that theory, and with a system in Too Human's dynamic. You can adjust it, and you can look around, and there is a free look in Too Human. But really, the whole goal is freeing you up, so you don't have to worry about the camera, and it does show the best angles possible in each case.

We have played all the Silent Hills, and they were really good games. I think God of War, Prince of Persia, Eternal Darkness... once we started doing the stuff awhile back, people really started to see the power there. Being able to do this stuff, I was just so happy that we weren't looking at Lara Croft's butt all the time. I just felt that was so uninspiring.

It's really funny. You mentioned that a director would never let you choose the shot, but for a while, they were trying to do that with DVDs. Ultimately, that only wound up in the realm of porn, and then it's gone. So it's really funny that it made its way down the ranks.

DD: It was a blip on the radar. I remember the multiple angle thing, and I remember going, "I don't even care." It's a lot more work, too, to do the multiple angle stuff. I really think that we're in such a hardcore state when people say, "I want to control the camera. I must control the camera." It's only because we haven't found sophisticated enough ways to remove that from the player so far. That's hopefully what we're trying to do with some of the stuff we're doing.

It's extremely difficult, obviously, because you have rudimentary AI that is telling these objects to go here and move around there, and do pathfinding and things like that. Things are going to get stuck in walls, and guys are going to be where you can't get them, and it's just going to happen. If you can't see them and they're killing you from off-screen...

DD: That's broken.

And when you have a large game, it's kind of impossible to fix all of that.

DD: We're going to put that to test pretty soon. Too Human's pretty big, so we'll see. I look forward to seeing... hopefully you get the chance to play sometime. I think there's definitely compelling points. It's just that it's really hard to do. It's not been done a lot because it's very difficult. We've done research and development in that for several years now, in working with professors from the University on the rules of camera and creating artificial intelligence. That's probably the most significant amount of R&D we've done in the entire company, and it's all basically being able to speak the language of film, which I think is very important and crucial, and I think our industry is missing right now.

I think that we have so much more power within interactive media to do things that films could never do. If we were to constrain ourselves and fetishize film -- which some people do -- it would be a real hinderance to the growth of the industry.

DD: Once again, it comes down to what I said earlier, in my eyes. Take the gold nuggets, and throw out the rest. If we try to do something that's one-to-one, we're ultimately going to fail. But it's just the similarities, and being able to reference -- how many people here do you think are able to do that? Very few.

If we are the eighth artform, and we're the next step from film, which was the seventh art, you'd think everyone should know what Griffith did and what films he did and why they were good and why they were bad. That's why we created the Academy Of Interactive Arts & Sciences -- to give that foundation to people, so they can build from it and hopefully be able to expand and go and stand on the shoulders of giants. That's what I think it's all about. There's literature that we can draw from. There's radio, television, and movies. It's just really, really strong.

It's weird to me that the language of film -- as you mentioned in your talk just now -- is something that people can understand intuitively. But the language of games -- all that we've created so far -- seems to be based off of technology, except for genre things and stuff like that. Our language is like parallax maps, and procedural X and Y, and things like that. We haven't really come to an agreement on what things are, and I think it's because we have a lack of proper criticism.

DD: I totally agree.

Which is a fault of people like me for not doing it, but I haven't had time!

DD: That's an amazing tangent, and we could go on for ages, I'm sure.

Do you think that it's a problem or a symptom of marketing, or of the wellspring of inspiration that people bring to the table, that we seem to go to very limited sources? You were talking about how we could go to literature or whatever, but it seems like most games seem to be inspired by, let's say, Aliens, The Matrix...

DD: Oh, it's terrible, yeah.

Do you think that that's because of the creators, or because of the marketing? I have this feeling that it comes from both directions.

DD: Sure. I think everyone's guilty to some extent. In the end I think it comes down to the fact that there's not enough time. People are looking at this medium and -- how long does it take to make a movie? A year? Maybe a year and a half?

Well, sometimes six months. Shooting, or pre-production to post-production?

DD: On average. I don't know. Anyway, it's shorter than video games. Movies cost more, and they make more, and the old days -- we're all victims of our history. Video games used to be really cheap, be really short to make, and make a ton more money than movies, so everyone got in the industry. Everyone wants to go back to that. But now what's happening, when we're talking about non-linear directions and stuff, is it's becoming more expensive. There's going to be a point in time where video games cost a lot more than movies, but if they're saturated enough, it won't matter, because they'll make more money.

But there's always this pressure to conserve and try to be as profitable as possible. I think that's good. There's nothing wrong with that, and we should always strive for that. But I think that's really what lends itself to the lack of people talking and the lack of communication. As an example -- and I'm guilty as well -- I fly out tomorrow morning. I landed last night. I'm really busy at work, and I would really love to stay and talk. There's a lot of interesting people. It seems like a great conference. But I've got to go home to make sure Too Human is good.

It's a serious problem. I was talking to Harvey Smith last night, and we was like, "Yeah, I had to take two days off of work to move, because I had to move into a new house. Moving furniture for two days was the biggest break I've had in so long, and I feel so relaxed now, because I had those two days." It's like, how can this be?

DD: It's a problem in our industry.

It's a huge problem, and it needs to be fixed. As long as people are willing to do it to themselves, it's not going to be fixed.

DD: It's changing.

He was saying that he feels like there is an inherent masochism in creative people, which is kind of true. You have to sacrifice yourself for the art. You really want to get your vision across and make this really awesome thing you've been trying to make. Anything else comes second to that.

DD: We have to be responsible. One of the things that I try to do at Silicon Knights is make sure that peoples' personal lives and their health is more important than the project. I've seen it across the board. If people are working really hard and their personal life falls apart, the professional life is soon to fall off. There's not enough money in the world -- at least I don't think so. I guess maybe Silicon Knights is lucky enough that everybody is not driving Lamborghinis.

We're from a standpoint of, "We work really hard, and we try to do the best thing that we can." At the same time, we realize that you can make it big, but assume you're not, and just try to do the best that you can. Silicon Knights is grown up now so that all the people who have been with the company for fifteen years or so have kids, and you have to be able to have a life. You can't say, "I'm taking two days off to move." That's insane. When we're in crunch times, you really need to push back and look at the battlefield and say, "Our troops are tired. We need a break."

Correct me if I'm wrong, but my perception of Silicon Knights is that you have been able to take the time to finish stuff, rather than rushing things.

DD: I think that's true, actually, when I compare it to other studios.

Too Human

How do you keep people from rushing it?

DD: It's hard call. You just have to believe in it so much that you never give in. You never give in to getting out the quarter versus -- I've equated it to this before, too -- my partner says, "Would you prefer a quick death, or a slow death?" A quick death is pushing as hard as you can, and it all fails and falls apart and everything closes down because there's just no more money or whatever.

A slow death is getting it out in time, making that quarter, and your game sucks. Then it comes to getting another game. You do the same thing, and that game sucks. So you're really looking at, "If you're going to die, do you want to die quick, or do you want to die over a prolonged period of five years?" It's kind of a samurai mentality on some level, but when it comes to getting the game out... that's the one thing with Blizzard.

I don't know how they've done it, but they're one of the few groups... and I'd like to think that we're in the same category, maybe on a smaller scale. Those guys have never sacrificed. I remember when they first showed Starcraft at E3, and it was not looking good. They just put it away, came back later, and said, "Here is a new Starcraft." We were like, "Wow, this is great!" Those guys, they have it down too. I think that's what it comes down to, just never rushing that game. Valve is another company who does the same thing.

They definitely do that, but they're really small, so they can afford to, and they have other stuff they're doing.

DD: They have a lot of money. I think it comes down to pain tolerance in many ways. It's an exercise in pain tolerance -- how much pain you can endure.

One thing about the slow death is you can spend a lot of time and release your game, and the game still sucks. And everyone's like, "Oh!" That could be an even worse way to have a slow death.

DD: Then what you should've done is you should've killed your project. If the game's looking like it's not going to be any good, you should kill it.

It's kind of interesting, because Resident Evil 4 kind of bridges the gap in its development. They threw it away like, what, twice? And started over? And then they ended up coming out with something that's up to this incredible level of polish and precision.

DD: Yeah, that's very typical in the industry, though. The only thing that happened there was they made the mistake of letting people know it was in development too soon. So yeah, I agree totally. They did throw things out. There's a lot of companies that do that. Nintendo does the same thing, but they just never tell people when games are killed.

And Blizzard, for the most part, doesn't -- Starcraft: Ghost being the obvious example. But you know that they have to have done it multiple times.

DD: Oh, they've done it lots.

Everyone kills stuff, for sure.

DD: It's the ability to say, "This isn't good enough." It's a hard call sometimes, because you can love your baby. No one's perfect all the time, and hopefully you have a disciplined group that can do the best that you can. It's a really tough game though.

Well yeah, you love your baby even if it's got the epilepsy.

DD: That's right. It's always your baby.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like