Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Can any one person describe the entire state of the video game marketplace? Entrepreneur, author, and Epyllion CEO Matthew Ball is certainly giving it a shot. The man who wrote "The Metaverse" is out this week with a slide deck full of data and analysis capturing the economic headwinds facing the business.

Ball's presentation gets to the heart of a very uncomfortable fact: according to analysts, video game spending didn't just fail to grow after the COVID-19 pandemic, it dipped 3.5 percent in 2022 and only climbed back a few percentage points by the end of 2024. Other data points, like a declining amount of playtime in games, are also enough to trigger game developers' anxiety (and mine!).

Ball identifies the slowing growth as being a symptom of major interlocking growth drivers of the period between 2011-2021 (when consoles and mobile devices exploded in capabilities and new social networks came online) losing steam. It's not a pretty picture, but this is a business built on solving big problems by staring them right in the face.

His lengthy explanation of the complicated market effects at play might warn investors and executives from investing more in the video game business—but that leaves and opportunity for savvy developers and leaders to slip in and find victories where others retreated.

I have no doubt this slide deck is bouncing through the inboxes of various studios right now and sliding across the desks of different C-suite execs. If you want to make the most of Ball's data, you'll need to think about how it applies to your day-to-day life. Here are a few takeaways that might resonate with rank-and-file developers.

This is probably thuddingly obvious to many of our readers but Ball's data makes a very clear point: video game budgets are too dang high. The amount of money invested in individual games is becoming more difficult to turn a profit on when a fewer percentage of players are picking up new games every year. "Excluding annual releases, but including sequels, only 6.5 percent of gametime in 2023 was for new games," Ball writes. "Always On" games-as-a-service titles released before 2019 earned the most "gametime" in that year. "Tens of billions in development and marketing investment and thousands of games competed for that 6.5 percent of total players hours (and four titles won half of it)."

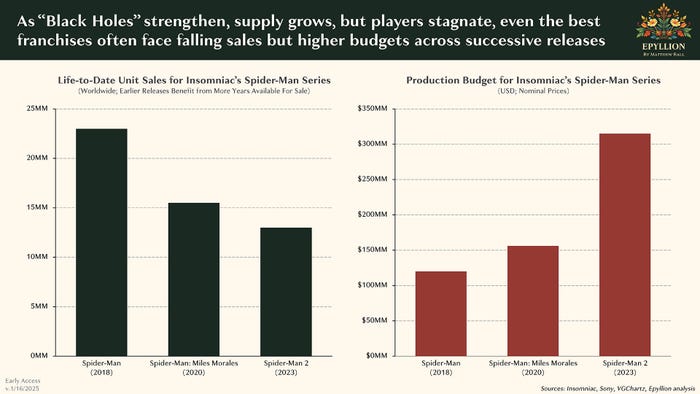

Marvel's Spider-Man 2 is the unfortunate poster child for Ball's breakdown here, as his breakdown of sales versus budget of the widely beloved sequel relative to its predecessors shows the heart of the problem. The series' production budget shot from just over $100 million to over $300 million across three games (Miles Morales clocked in at just over $150 million), but lifetime sales of the series haven't increased exponentially.

Image via Matthew Ball.

Pair that against the small market share the series is competing for and the economics become rough. I don't know the fate of the budgets for future Marvel's Spider-Man games, I do know Insomniac is aware players aren't necessarily seeing the payoff of the increased spending, a fact that came out in the frustrating dump of leaked documents obtained by hackers targeting the studio.

Now here's where things get hard: how do you reduce budgets? There are only three major tools: lower salaries, lower development time, or lower headcounts. Each has frustrating tradeoffs that in many cases, punish workers and reward executives who ballooned the budgets in the first place.

Ball's data points to two obvious ways government regulators could influence the game industry—one explicit, the other implicit.

The implicit argument isn't clearly stated, and I wonder if Ball would take issue with my analysis. But reading between the lines, an understated challenge of bigger budgets is this: game development is hit brutally hard by the cost of living and inflation. As we discussed last year, the same number of developers you stick on a game costs dramatically different depending on the country you're operating in. Developers in higher-cost-of-living regions are being undermined by ones in lower-cost-of-living regions, and developers in the latter territories risk being exploited because they have less agency to leverage better wages.

Image via Matthew Ball.

Ball's explicit argument targets the purported monopoly Google and Apple have on their mobile platforms. He says that if the iOS and Android app platforms need to "open up." New stores could, among other things, drive competition that lowers the 30 percent "platform fee" claimed by Google and Apple, drive new discoverability methods that connect players to a wider variety of games, and spark innovation for new genres of games.

Both topics may require industry leaders to grit their teeth and press local and national governments in support of regulatory action. Industry lobbying groups to date have largely focused on tax breaks and legislation surrounding the import cost of parts and access to internet bandwidth. That's a lot of work invested into legislation that primarily benefits the world's largest publishers and studios.

Just like Mr. Smith, it's time for video games to go to Washington (or London, Ottowa, etc. etc.).

Speaking of new game genres, Ball's analysis concludes that the emergence of new game genres could be a shot in the arm for the video game market place. He points to the era of the battle royale genre's as being the kind of event that can drive new growth. The industry, he says, could use a shot of innovation.

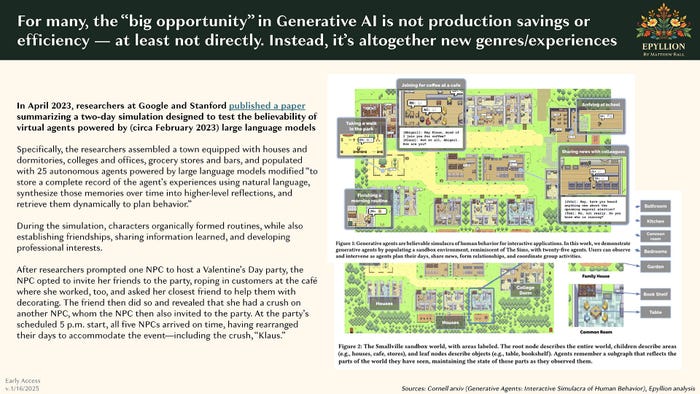

His suggestions for where new genres might come from are concentrated on possible technological advances in "mass concurrency," "high-bandwidth data streaming," "higher-persistence game worlds," and "cloud native games." His analysis of generative AI also focuses on the technology's potential to introduce new genres, as some developers like those at Hidden Door are experimenting with.

Image via Matthew Ball.

Ball's technology-focused thinking isn't out of place, as many previous industry advances came out of graphical and rendering advances. But there might be a missing variable here: unpaid modding.

Many breakout new genres of the 2010s began life as mods (born of unpaid labor) for entirely different games. That goes for MOBAs, battle royale games, tactical shooters like Counter-Strike, and more.

That trend muddies of the waters of where developers can find true innovation that will land with players—and who benefits from it. Valve and Blizzard jumped into action to try and profit off genres built on mods of their games. Meanwhile, Brendan Greene was lucky to find a business partner that could turn his ARMA 3 mod into a full game, but Epic Games fast-followed with Fortnite so hard it became the defining version of the genre in the United States.

A bubbling example of this phenomenon right now might be Grand Theft Auto Online's roleplaying servers. Their popularity speaks to Ball's analysis that the next generation of video game players prioritizes social play over competition, and right now Rockstar Games is the beneficiary of unpaid time and labor from players setting up their own mini improv theaters. Will Rockstar build on this audience after the release of Grand Theft Auto VI? Will other developers swoop in to try and eat their lunch?

Video game analysts from the early 2000s have a fair bit of egg on their face as one of the few bright spots for the traditional video game marketplace is consistent growth in the world of PC games. Declining sales around 2010 led some to think consoles and mobile would inevitably beat out PC games, which were (and sometimes are) difficult and fiddly to get running.

"Twenty years ago, PC's share of non-mobile console spending was 29 percent. It's now 53 percent," writes Ball. "And while console [spending] has stagnated since 2021, PC has grown 20 percent."

Before you jump out of your desk and greenlight another generation of flight simulators, you should check out why PC spending is growing. "The largest share of Steam users now use Chinese as their default client language (which probably underrepresents China's total share of Steam users)," says Ball.

Additional data he shares shows that Chinese client language users are among the group that has grown the most on Steam from December 2021 to September 2024. This group represents what many publishers hope to reach—a "fresh audience" with different tastes and interests than the more calcified existing market.

But while Chinese player spending on video games has grown by $39 billion since 2011, only 20 percent of their domestic spending goes to imported titles. Spending on imported titles declined five percent from 2023 through 2024. Ball compares this phenomenon to one also taking place in the film industry: locally-made entertainment is outpacing imported entertainment across the globe in China, Nigeria, and India.

Image via Matthew Ball.

Box office hits like Wandering Earth, A Tribe Called Judah, and RRR are cinematic cousins of Black Myth: Wukong—entertainment produced by local artists that are wildly popular in their countries of origin and also find audiences abroad.

"As foreign markets grow, their domestic production capabilities and supply grow too, and this always results in national preferences then shifting to local product," Ball observes.

There's opportunity for the game industry to meet this moment. We've seen rustling from South Korea about expanded interest in triple-A games alongside the country's longtime passion for free-to-play multiplayer titles, and regions like Brazil and Eastern Europe are following similar trends.

If you're not in those regions, you might wonder how your neck of the game industry can benefit. For now, the best I can offer is that if overseas audience spend more time on consoles and PCs than mobile devices, developers have an opportunity to catch some of that interest by investing in localization.

Woven through Ball's analysis is another long-running trend: how players and why socialize through games is changing.

The Roblox phenomenon, for instance, isn't just about younger players being drawn to blocky graphics and user-generated content, it's that the platform's flexible tools have become a haven for self-expression and social play. We can again look at the proliferation of Grand Theft Auto Online roleplaying servers as another data point in this phenomenon, and outside of games, the increasing growth of chat platform Discord.

"One in five Discord users (or 40 million total) use the app to stream gameplay to their friends each month—and just under one in three watches monthly," Ball notes. It's a piece of social glue that accelerates interest in games like Palworld, Smite 2, Phasmophobia, and Lethal Company.

Discord's list of users playing Steam Early Access titles as a share of total observed players is largely loaded with co-op multiplayer games, but also features single-player titles like Fields of Mistria, Hades II, and Manor Lords. Ball describes this as "disproportionate" game discovery behavior.

Image via Matthew Ball.

The developers behind these games probably didn't do any weird science studying the habits of Discord users (unless they did, in which case, hey reach out to me I want to know what you learned), but enough of them have succeeded on the platform in a way that suggests studying how players engage with and use Discord might be a vector for developers to grow, explore new genres, and succeed in 2025 and beyond.

(And Discord may not deserve all the credit here—social apps across the globe likely drive similar behavior in different regions).

I'll be honest here. When I first read Ball's report, I came away with some degree of anxiety. The human brain struggles to wrangle numbers like these, and it's easy to spiral into an unhelpful spree of if->then statements that make a decline in billions of dollars in spending feel like the end of the world. The problems and solutions are so big and abstract that if you aren't a big-money decision maker—just a humble programmer, artist, designer, or a writer like me—you can feel like you have no agency in a field you deeply love. And even if you have the power to greenlight a game, what if the games Ball is proposing aren't the ones you want to or even can make?

The solution, I think, is to look at Ball's data and analysis as a map. Maps don't serve one purpose—they lay out the territory as best they can so another traveler can navigate it. Plenty will read Ball's map and see "X marks the spot" where others will see "here there be dragons."

You don't have to change or fix the game industry. But to make the game you want to make, having a map handy might keep you from sailing into dangerous waters.

You May Also Like