Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest Gamasutra column, game lawyer Tom Buscaglia discusses the art of the game development contract, particularly focusing on making sure the developer shares ancillary revenue streams - from merchandise to in-game advertising - with the game's publisher.

Let’s start with a few basic concepts. Developers make games. Successful developers sell their games. Publishers are the vehicles through which developers sell their games. Too often a developer says, "We just want to make great games" while the publisher says, "We just want to make money."

Unfortunately, that is all too often the result. The developer makes the game while the publisher makes the money. Why? Because the publisher is in the business of making money, not just in the business of selling games. That means maximizing their revenue from the exploitation of all aspects of the games they sell. If a developer believes otherwise, even if the developer makes money, they may well be getting the short end of the whole deal.

There are some things that publishers excel at and one of them is coming up with new and innovative ways to commercially exploit games. This means more revenue from the games we make. Of course, we have to be savvy enough to ask for our share of this additional ancillary revenue to get some.

Often the developer is so focused on getting a publisher to sell their game that all they look at are the royalties from game sales. If all the developer asks for is a portion of the revenue from the sales, what’s all they’ll get, regardless of how much ancillary revenue a game generates. And publishers are getting really good at finding innovative ancillary revenue streams from the games the sell.

A developer I met at GDC contacted me a few months ago. They needed my help on a publishing deal with a major publisher. These guys had been doing licensed games for years and making a decent living doing it. Now they had a shot at releasing their own original IP.

The publisher wanted the game to add to their portfolio for presentation to the press at E3. And they were willing to do the deal allowing my client to retain ownership of their IP with a favorable royalty rate on sales. Tentatively, a really good deal. So, it came to me to review the contract and see what I could do to earn my fees by making this deal as sweet for my clients as possible.

As expected, there were some of the usual "minor" issues with the contract that had to be addressed, and a few twists. Although the royalty split as acceptable, there was mention of the publisher’s right to exploit several additional potential ancillary revenue streams with no participation by the developer. In-game advertising, for example, was included with no revenue split.

As expected, there were some of the usual "minor" issues with the contract that had to be addressed, and a few twists. Although the royalty split as acceptable, there was mention of the publisher’s right to exploit several additional potential ancillary revenue streams with no participation by the developer. In-game advertising, for example, was included with no revenue split.

There was also a vague reference to the publisher having a right to B2B relationships relevant to the game, but no description of exactly what that meant. When pushed for the details of what sort of B2B deals they might be looking at, the publisher just danced around any meaningful answer. Of course, this sort of behavior made me even more suspicious that this might represent a clever new revenue stream from the game. Call it my jaded lawyer’s suspicious nature.

Eventually, through some rather persistent negotiating, we were able get the publisher to agree to pour any in-game advertising and any B2B revenue into the revenue pool. I pushed for a straight 50/50 split on this ancillary revenue because, in effect, this is found money for everyone involved. And as my old buddy, super agent Barry Friedman, likes to say, "All deals start at 50/50!"

But, the publisher held firm to applying the same royalty split to all revenue from any source. But just in case the publisher found any other way to exploit the game that was had not covered, I also include in the contact a "catch all" provision pouring any and all revenue from any commercial exploitation of the game from anywhere into the royalty pool to be split with the developer.

Of course, there is always the accounting of these revenues later to be dealt with -- maybe even an audit or two. But this could ultimately mean a significant amount of additional money for the developer.

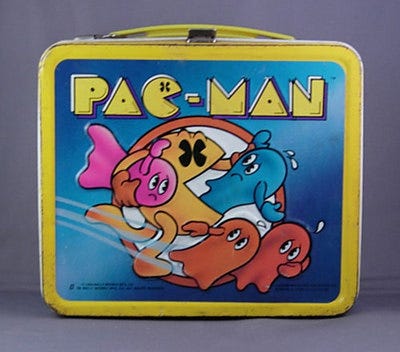

As I said, publishers are not the business of just selling games; they are in the business of making money. Any time a new or unusual revenue stream comes into play, it is the publisher who initially benefits. This includes anything from lunch boxes and action figures to movie rights. For example, when in-game product placement began, developers rarely saw any part of these revenues... at least until they started asking for it.

The same thing occurred with in-game advertising. Again, this was additional revenue to the publisher long before developers ever saw any share of it. But as the development community became aware of these revenues, developers started asking for, and getting, their piece of the pie.

Developers owe it to their own success to be aware of and always seek to participate in these new inventive ways to commercially exploit the games they make. When negotiating your deals, always push for an even split on these ancillary revenues.

Developers owe it to their own success to be aware of and always seek to participate in these new inventive ways to commercially exploit the games they make. When negotiating your deals, always push for an even split on these ancillary revenues.

After all, they do not have any of the risks or costs associated with their distribution of the game itself. No funding, no marketing budget, no manufacturing costs, no distribution costs and no platform license fees. Just third party deals that bring in revenue outside of the traditional distribution channels.

I always attempt to apply the same revenue model to sublicense deals as well. Although most major publishers now have direct distribution worldwide, often second-tier publishers only distribute the game in one territory -- but secure worldwide rights. Then they sublicense the game in other sub territories.

On these deals the regional sublicensed publisher often provides an advance to the publisher for the right to sell the game in that territory and gets a localized version of the master. In effect, they assume all of the marketing and distribution risks for the game in their territory. But instead of getting the negotiated royalty rate in these sublicensed territories, the developer only gets a percentage of the net received by the publisher -- that is, a percentage of a percentage.

For example, if sublicensed distribution deal is at the same rate as the primary distribution area, the developer takes a huge cut. At a 25% royalty for a game that, after allowed deductions, nets $24, the developer would get $6.00 royalty per unit. But in with a 25% sublicense, all other things being equal, the developer ends up getting only $1.50 per unit, and that’s assuming that the game sells at the same price point. Ouch!

The publisher, however, has none of the marketing or manufacturing expenses that it has in the core territory where it actually manufactures, markets and distributes the game. Often second-tier publishers actually generate more revenue from these sublicenses than they do from direct sales, but with little or no risk or expense.

So, if there is going to be any sublicensing, do your best to carve it out and get it treated just like any other ancillary revenue. Go for the same 50/50 split you should be pushing for with any other the ancillary revenue, and for the same reasons.

So, always look for additional ways that your game might be being monetized. Think about what risk these revenue streams pose to the publisher. If there is little or no risk involved, press for a higher royalty rate on these revenues. Your publisher may not like it, but there is a valid logic to this arraignment and a strong argument in favor of it as well. You may not get it, but it is sure worth asking for. And one thing is for sure with publishers -- if you don’t ask, you don’t get.

(© 2008 Thomas H. Buscaglia. All rights reserved.)

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like