Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

You can convince your publisher to let you expand your game's design to incorporate exciting new features -- but how do you prevent that from drowning you? Game Law brings you a cautionary tale based on the experience of a departed development studio.

A few years ago, one of my client studios was just starting out and had landed their first game deal. It was a bare bones sort of deal with minimal funding. But the game that they pitched could have probably been delivered within budget.

The game was a PC FPS built around a multiplayer theme, with a ladder system for the single-player using the same maps as the multiplayer. The AI for the single player was pretty much within the scope of what was built into the engine they were using. The PC release was to be followed, at the publisher’s sole option, by an Xbox version.

The agreement with the publisher was a typical staged milestone deal and had the design document attached to it. These guys were in heaven. After doing contract work for a few years, they finally had their own game based on their own original IP.

They went out and rented cool offices, got new computers and brought on a few additional developers to bring their team up to size. Everything was good. Each of the members of the team was extremely talented and as a team, they were amazing. And they were totally stoked. But, it was their passion, combined with a lack of discipline, that was their downfall.

As they began development in earnest, they realized that although the single player ladder model would be OK for the PC, it would not make it on the console side, where multiplayer had not yet gained any acceptance. Without a solid single-player experience, the game would never be green-lighted by Microsoft. The publisher contract was back-end weighted, so the Xbox part of the development followed the PC, with more money allocated for the development of the console version of the game.

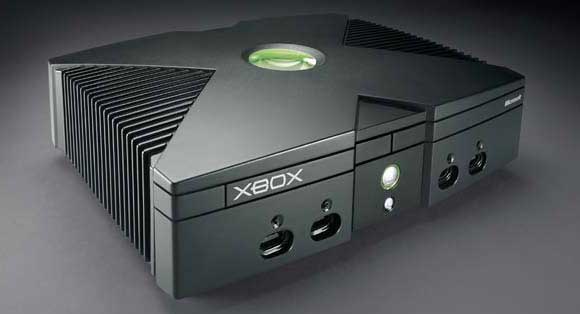

The original Xbox. Nostalgic, eh?

The original Xbox. Nostalgic, eh?

The multiplayer design was done, but that single-player design challenge was out there. As they brainstormed about all the cool things that could be incorporated into the single-player game, they began to develop their design. The concept: a 21 level linear adventure with AI-driven NPC allies and enemies, a real multiplayer experience in a single player game. Awfully ambitious. But they believed that they had the talent to do it. (And in my opinion, they did.)

When they took this new and substantially-enhanced design to their publisher, the publisher was thrilled. The team also told the publisher that rather than waiting to do this for the Xbox version, that they thought it would just make more sense to do it in the PC version first and then port it to the Xbox. After all, why not deliver all of these cool features on the PC as well? The publisher was all for it. This was gonna be great! This is also where the title to this article comes into play... Discipline and the Up Sell.

At this point they should have taken into account more than just how cool this game was going to be. But their passion blinded them to the harsh realities of running a business. The scope of the project had changed substantially. More features, more levels, a more demanding AI; all would necessitate more time to completion.

And as we all know (or should know) more time means more money out the door for salaries and expenses. Sure, publishers get upset when a game slips. But the real problem with slippage is with the additional operational and personnel costs to the studio.

This was not even a slippage situation. This was a situation where the studio knew that the new, expanded design would require significantly more time to complete. And while the game that they originally sold to the publisher could have been made within the original budget, this new game would ultimately take twice as long to build, which meant it would cost twice as much to make.

This did not have to be a disaster in the making. If properly addressed, it could have been a huge opportunity to make the game they wanted to make and get enough money to do it. It’s called “Up Sell.” We have all had it happen to us. You go in to buy a used car and they show you new ones. You want the simple version but all you are hearing from the guy in the appliance store is all the features that the high-end model offers. “But we’re game developers, not cheesy appliance salesmen,” you say. Sure, but the example still holds. And the point is even more important because we are not salesmen trained to do this.

Many new developers just want to make the best game that they can. But if they do not condition that desire with discipline. The mantra has to be “We want to make the best game we can within our budget,” or their dreams of having their own studio may well never come true. Call it slippage, feature creep, “going the extra mile” or whatever else you want. But if you commit your studio to do anything without getting paid for it, I call it just plain foolish.

Our example was a perfect opportunity for an up sell. The game budget was back-end loaded with most of the advances tied to the Xbox option. But under the new model, by shifting revenue from the Xbox to the PC version, which would now have many of the features reserved for the console title, more money would be available for the PC development.

And the additional features and expanded design would also require more time and, therefore, a larger total advance. The thing is -- the publisher loved the new design. The selling part of the up sell was already done. The part that was lacking was the new price. This ultimately cost the studio everything.

They brought me in to help out in late in the project. I was able to renegotiate the milestone payment structure to move more of the back-end payment to the front end because they were getting into difficult financial straits. But by that point they were already fully committed to the revised game design. So, reverting back to the original game they sold to the publisher was not an option. Though the game was released, the studio took a huge loss on it and shut down shortly thereafter.

Using the magnificent magical prism of 20/20 hindsight, it is easy to see what they should have done. After all, figuring out what should have been done is always way easier than figuring out what to do in the first place. But maybe this article will help someone else avoid this particular pothole on the road to building a successful studio.

Here, the additional features and revised game design were great. And getting publisher buy-in was also right on point. In fact, the more the publisher is salivating for the enhanced project, the better off you are. But (here’s where the discipline comes in) at this point a full realistic analysis of the revised project schedule and the impact that this will have on the budget needs to be done. Yeah, I know... this is not what you got into game development to do. But if you want to run a studio, you better cowboy up and do it or find someone else to do it for you!

Right when the publisher fully buys into the new design and features is the right time for the up sell. Just go to the publisher with the revised budget and let them know how much more time and money they will have to advance to get this great “new and improved” game. Of course, at that point you also need to be disciplined enough to say (and mean) that if you don’t get the new budget, you just can’t make the enhanced version and then just deliver the game as you initially promised and sold it.

If the publisher sees the additional value, they will pony up the additional dollars to make it happen. And if not, you’ll just have to save all these cool additional features and enhancements for the sequel or your next title. This combination of “Discipline and the Up Sell” can go a long way toward helping build a successful development studio.

A few parting thoughts -- OK, one reason I picked the topic of “discipline” is because I figured the editors at Gamasutra would come up with some really kinky pictures to go with the article. [No luck. -- Ed.] And, in case you are wondering what happened to the folks at the studio in our example, well, it seems that every cloud does have a silver lining. Although their studio is long gone, all of the developers involved are doing well and have extremely successful careers at some of the top studios in the industry.

Till next time, GL & HF!

(© 2007 Thomas H. Buscaglia. All rights reserved.)

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like