Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Japanese developer Treasure has created games from Gunstar Heroes through Ikagura and Bangai-O -- Gamasutra quizzes CEO Masato Maegawa on the company's storied history and future.

Treasure has long forged a defiantly idiosyncratic path over the course of its nearly 17-year history.

Founded in 1992, the company immediately began working on the action games which would become its signature -- beginning with emblematically side-scrolling shooter Gunstar Heroes, which was released in 1993 for Sega's Genesis/Mega Drive platform.

Over the years, Treasure has balanced creating its own gameplay-intensive titles, such as Ikaruga, with carefully working with established series -- as was the case with the Nintendo-published Wario World for Gamecube -- and licensed properties, such as fighting games based on the popular manga and anime series Bleach, again with Sega.

Most recently, the company has revisited its Bangai-O series with a new installment on the Nintendo DS, Bangai-O Spirits. Originally released to the Nintendo 64 in Japan only and followed up on Sega's Dreamcast, the series features massive stages of shooting and fighting action.

This time around, an innovative level design tool and sharing mechanism, which allows users to record audio from the Nintendo DS and post it online to trade levels -- led to an interesting promotion in which professional designers from studios such as Infinity Ward and Foundation 9 created in-game levels.

This article talks to CEO Masato Maegawa about the inspiration for the Bangai-O remake and its new features, discusses the titles the company has released throughout its history, and raises questions about where things can go from here -- presenting a comprehensive Treasure overview as we head into a new year.

With Bangai-O Spirits, where did the idea for the Sound Load level trading come from?

With Bangai-O Spirits, where did the idea for the Sound Load level trading come from?

Masato Maegawa: Well, basically, back during the 8-bit generation of computers, people saved their data on cassette tapes, recording audio pulses that represented 0 and 1.

We realized that you could still do the same thing today if you wanted, trading MP3s with each other. Of course, that probably shows how long I've been involved with the computer industry (laughs) -- but really, it's not a new idea at all.

Once we got into the PSP era, developers got a lot more freedom to have downloadable content and patches and so forth, but there's really no easy way to connect a DS to a PC. As we tried to find a way around this, we came up with the Sound Load solution.

I should add that now that the DSi has been released, that situation might wind up changing. Of course, what we have right now is pretty good! In terms of exchanging data, Sound Load is probably the best solution available at present.

What makes you say it's the best solution?

MM: Well, I don't how know it is overseas, but I mean that in Japan, you have people opening up websites devoted to the game where you can freely download and exchange data between other users. That's what I mean. Putting things up on YouTube, and so forth.

Basically, Nintendo tends to set up their online structure with safety and security as the number-one priority and freedom as the second item on the list. You can't connect your DS to the internet and just do anything you want to with it.

You would need to exchange friend codes before trading stages if you were doing it [via Wi-Fi], but doing it this way lets gamers exchange data without any of that, without getting Nintendo involved. (laughs)

And I'm not saying that Nintendo's strategy is the wrong one, but asking gamers to get friend codes from people they've never met or talked to before is enough to make any of them a little hesitant about online. It's not as fun, either, if you're only able to share levels with your personal friends.

It's sort of like how they used to sell records where the last track would be a data track, and you could read that into your ZX Spectrum and play a game or something.

MM: Were you guys around for that era?

We read about it on Wikipedia.

MM: (laughs) You're still pretty young!

What is the fascination with light and dark?

MM: I wouldn't call it a "fascination," exactly, but what it does do is make the game's storytelling a great deal easier to understand. There's that aspect to it, but I wouldn't say it's something we expressly think about.

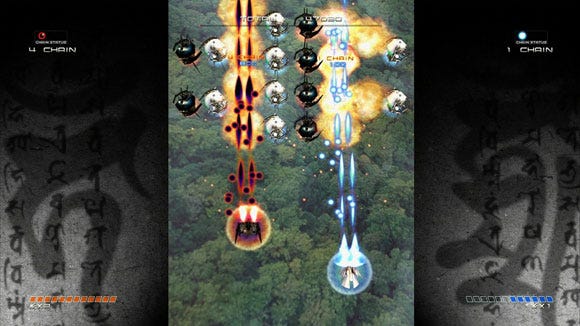

For example, the core gameplay of Ikaruga revolves around switching between white and black and absorbing shots of the same color as yourself; that was really more of a gameplay design invention than a color-based one. Working with two of a particular type of thing is more interesting, and more profound, than having just one.

What do you feel is too complicated? In Bangai-O Spirits, there are so many weapons available that it can get pretty overwhelming.

MM: I wouldn't see it as being complex; I see it as having a wide range of options to choose from. The previous Bangai-O offered a fairly limited range of weapons -- there was homing and so forth, but not very much of any given type.

One of our aims with Spirits was to add a wider variety of close-range weapons, like bats and swords, to help enhance the game's basic action. We went through a series of "having this weapon in the game would be pretty neat" phases, and the weapon count wound up zooming higher and higher as a result -- but having that wide range doesn't inherently mean that the game's more complex.

Have you played Portal before?

MM: I know about it.

In that game, you have red and blue portals, which you can place anywhere you want with the left or right triggers. If you enter the red portal, you come out of the blue one, and vice versa. It's a very simple game design, but the puzzles created with it get very complex. You can make your own custom stages, too.

MM: Sounds pretty fun.

Looking at that design, I wonder if the makers were fans of Treasure games. It's the same sort of idea -- a simple concept lending itself to complex gameplay. If Treasure made an FPS, what sort would you like to make?

MM: I could see that happen; I mean, there are a lot of people in the company who like FPSes. There are a lot of extremely well-made FPSes out there, though.

We'd have to make something really original, because simply making a well-made FPS isn't going to be enough to separate ours from all the other ones already released.

Design is at the center point of a lot of Treasure's games. How long of a turnaround is there between coming up with an idea and creating the prototype for it?

MM: I don't know how often we do that sort of "prototyping." The first time we did a prototype in the way you're stating it was with Ikaruga, because we really had no idea at all how fun the idea was until we actually had a chance to play it for real.

Otherwise, we don't make those too often. More often, you start with the idea, and then you build the game around that, putting elements in and taking them out in a trial-and-error process.

Treasure's Ikaruga

Treasure's Ikaruga

You can't really understand Ikaruga on paper.

MM: You can't.

It's that sort of game, isn't it? You can easily explain what the game's like to someone now, but if the game didn't exist beforehand, it'd be a lot more difficult.

MM: Yeah. In the case of Ikaruga, there wasn't any way that simply telling people about it in presentations would be good enough -- we had to have something running to show people.

That's the main reason we had a prototype early on in the project. You needed something to show.

Did you ever go to publishers with only a concept on paper to show them?

MM: You can do that, but you know, a project document is a pretty thin piece of work. It's, like, a couple pages. (laughs)

That's what I like about them.

MM: If that's all you have, then your publisher better have a lot of trust in you to accept it! Our basic game ideas are pretty simple, though, and usually the planning documents and art that we have is good enough to present from.

I don't really write them myself, but lately it's been seeming like a ton of documentation and design material has to go into planning documents [of other companies]. They're like over a hundred pages or so.

Writing lots of Excel spreadsheets and so on.

MM: Exactly. You have to be sure that your concept is focused and plan to everyone; once you have that, you start building the game and finding ways to make it more fun as you go.

Was the concept for Ikaruga decided on from the start? It didn't change any afterward?

MM: Once we had the prototype for the idea running on the PC, it didn't change much at all after that.

With LittleBigPlanet, when those guys want to show each other a new idea, they'll do it within the engine and show a video of it, but it's actually useful because they have the tools built in.

MM: I've often found that I have this wonderful idea in my mind for a level or a concept for a game, but then when I actually try making it, it all falls apart in reality.

In that way, having the basic construction process be as simple as possible is a good thing for us -- and, with LittleBigPlanet, for the users working with it.

Some of the [user-created] stages people have been made are incredibly complex -- maybe too much so, even -- but people are doing great stuff if they put a ton of work into them, working together on the net. But my friend and I have probably spent over 200 hours playing Bangai-O Spirits, and the stage editor on that game is just excellent.

Some of the [user-created] stages people have been made are incredibly complex -- maybe too much so, even -- but people are doing great stuff if they put a ton of work into them, working together on the net. But my friend and I have probably spent over 200 hours playing Bangai-O Spirits, and the stage editor on that game is just excellent.

MM: Well, thank you very much! I've played around with a lot of editable games in the past, but a lot of them have a pretty major learning curve.

It takes you a good two or three hours to even begin learning how to build anything. That's why being able to get started immediately was one of the main concepts of the editor.

You can see all the possibilities available within 10 seconds.

MM: It's easy to get in, but the more you mess with it, the more tangled it can get. (laughs)

What inspired you to make another Bangai-O?

MM: Well, we wanted to. (laughs) The director said "Okay, I want to do this, period!"

Did you want to have the stage editor in from the start?

MM: It was there from a pretty early point. Since our platform's the DS, we wanted to have something that used the touch pen, and an editor was the obvious choice there.

Did you use the editor to make the stages in the game?

MM: We sure did, mostly. The first version of the editor was a little rough for that stuff (laughs), but mostly, the stages were done with the built-in editor.

You've got to have some kind of editor when you're developing a game, right? Usually, if we just took our editing tools and gave them directly to the users, the learning curve would be so high that they'd have no idea where to begin with the thing.

If the developers know how to use it, then it doesn't matter how complex it is -- that's usually the thought process. But it was surprising how easy it was to make our editor for this game user-friendly, and it led to a lot of side benefits, obviously.

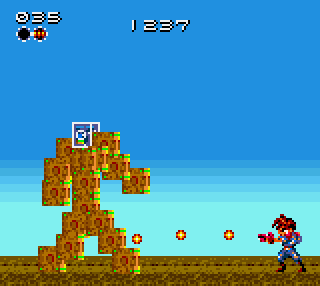

What was the inspiration for going back to Sin & Punishment?

MM: Sorry, I can't answer anything about Sin & Punishment 2 right now. (laughs) For now, keep on playing the Virtual Console version of Sin & Punishment 1!

What do you consider to be a "next-gen" game? Is something like even important to a company like Treasure?

MM: Well, that's what Sin & Punishment 2 is for... (laughs) I haven't really worked on a console since we made Ikaruga, but the Wii is what I'm working on now.

We're a small company, so it's kind of tough for us to build the resources to work on the PS3 or whatnot, but while the Wii isn't exactly a "next-generation" machine, it's something that we're doing our best to challenge ourselves on.

Since your company is small and you have to sustain yourself on a game-by-game basis, is it more important now than before to choose your choice of platform carefully?

MM: It's really a case-by-case thing. I wouldn't say, though, that I have a real preference for one console or another, when it comes down to it.

Really, the best platform out there is the one where I can get a game completed and published on; I worry about the game long before I worry about the platform.

Treasure's Sin & Punishment 2

Treasure's Sin & Punishment 2

How do you decide when it's time to cut a game, that it's not going to plan? It doesn't happen that often, that a game is publicly announced in Japan, but doesn't come out. It's happened a few times with Treasure.

MM: Well, when something really just isn't working out, then it's usually pretty obvious among the staff. Once that happens, chances are pretty low that you can just put your head down and keep plugging away at the game, release it to public, and expect it to somehow work itself out.

Does Treasure ever do internally funded development, or is it all publisher-based?

MM: Well, there was Ikaruga, we did publish that ourselves. That was self-funded.

In terms of games based on licenses, like Bleach, is it important to you that the game retains your own mark, or is more important to stay true to the license or what the publisher wants?

MM: If I had to choose between one of the two, then naturally it's more important that you pay attention to the original work and stay faithful to it, for the sake of the people who're buying the game for that name. But you can't hold yourself back completely, either.

That's one of the challenges of a licensed game: how much you're able to express yourself while doing everything else you need to do. You don't want to go completely off track from the original work, because you run the risk of messing everything up and annoying fans. You don't want reviews saying "The game is fun, but it's nothing like the anime!"

I don't hate the original Bleach, but I don't really have any interest in pursuing it; I've never read it. But the game is a lot of fun.

I don't hate the original Bleach, but I don't really have any interest in pursuing it; I've never read it. But the game is a lot of fun.

MM: Taking the individual things that make up the work's characters and putting them together in a way that works well game-wise is the key thing.

That makes it easier for developers to steer the game in the direction they want, and it makes it easier for the players, too, of course.

Does Treasure have any interest in making an arcade fighting game?

MM: Don't you think we're pretty much past that era?

Street Fighter IV could revitalize the market for it.

MM: Well, I don't know; when you're talking about making a full-on arcade fighting game, you're talking a lot of development resources required for a game that not everyone has the ability to get into in the first place.

Could you make one that uses two buttons? Like, punch and kick? Like a Neo-Geo Pocket Color game?

MM: I think we could figure out a good game system along those lines, definitely. It's the rest of the project that would be a pain to implement.

What do you think about the state of the shooter market right now?

MM: Oh, I think it's still good! (laughs)

Namco remade Galaga/Gaplus on the Xbox 360 recently, for example. A lot of American and European outfits are making shooters for XBLA and PSN.

MM: The thing about shooters is that if you make one that can find an audience, then you will never find a player base more devoted to a single title with any other genre out there.

Geometry Wars is well-loved by a lot of people who never play shooters at all.

MM: That's definitely an off-beat game in the genre. It's a fun one; I was definitely impressed by it.

When the PS2 Gunstar Heroes was released, was it your idea or Sega's to put in the prototype version?

MM: It was definitely Sega's -- in particular, the producer at Sega who supervises the Sega Ages series. He is a monster hardcore gamer; we would show him stuff we had lying around, any old thing, and he'd shout out "Ahhhh, I've got to have this, I've got to have this!"

Then we'd be like "Oh, great, what have we done?" (laughs) The prototype is really pretty close to the final version; there were some final tweaks seen in the retail game that weren't implemented yet in the earlier build.

Have you played the Brazilian Master System port?

Have you played the Brazilian Master System port?

MM: We supervised the production of that, actually. (laughs)

It was alongside the Game Gear version, and it was the first time any of us had ever touched a Master System, so it was pretty crazy.

How did you get so much out of the Game Gear for that port? It seemed like Treasure is really good at maximizing the hardware they're working on.

MM: We didn't make the Game Gear one, actually.

Oh, really? Who did, then?

MM: Well, they left the company, so I dunno if we can say... (laughs)

Radiant Silvergun's rarity is the stuff of legend these days...

MM: Legend? (laughs)

Well, lots of people in America know its name, and how hard it is to obtain a copy. Not too many people have actually played it. Now that downloadable games are more common...

MM: Oh, I think we'd definitely like to see it out there. But the situation around that game is a bit different from Ikaruga, so I don't know if we'd see it on Live. We did a lot with the Saturn version, too.

I think it'd sell pretty well. Microsoft would be up for it, I bet.

MM: Microsoft actually asked us if we could put it out. (laughs) We're thinking about it, certainly, but it's not as simple as just saying "OK, let's put it up." I mean, sure, with Ikaruga, we released it as is without having to do or add a great deal to the game and it was popular and well accepted for what it was.

But if you play Radiant Silvergun nowadays, it's certainly aged in assorted ways, and I'm not sure they're all good. (laughs)

One more obscure game is Silhouette Mirage. Do you have any plans to return to that kind of platform action experience? You've only had a few of those games, but they've all been good.

MM: That's sort of the same deal as before -- there's certainly a lot of requests out there for us to make a side-scrolling action game.

But, as before, there's a pretty big difference between saying "Yeah, that'd be nice" and actually doing it, because it's surprising how much work goes into making those sorts of games nowadays.

Do you ever consider growing the company more in order to do more of that kind of stuff?

MM: No. (laughs) Definitely not. It'd be too hard to keep the company in one coherent piece otherwise, because we're all here because we really love making games.

Having ten of those independent-minded sort of people in a group works great, but having a hundred of them would probably bring down the company. (laughs) I don't really see the merit in getting bigger.

Do you think that kind of mentality -- which is good, by the way -- can limit your ability to become really rich and stuff?

MM: I don't want to be rich. (laughs) If I get rich, then I won't be able to make the sort of games I want. You need to work at it, you know? If you keep thinking about making games that sell a lot, then you wind up unable to make the games you really want.

How many people are in the company now?

MM: About 20, I think. 20 or 30 is probably the best number, I think.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like