Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Hypocrite, Liar, Thief, Murderer...Games showed me I'm not a 'good' person, and apparently, I'm not alone. This is guilt in games--from the player's point of view.

In the face of a world that mocks the God who came to save them as well as us, admitting our common heritage as sinners—normal people saved by the grace of God alone–is difficult. So, many Christians attempt to cultivate an image of unpolluted righteousness, forming themselves into apparently shining examples of moral fiber.

I’m not saying this is a bad thing. We’re certainly meant to be examples. I’m asking the question: What do you do when even one of those jagged lines you drew in the sand turns out to be a facade? What do you do when you’re placed in an environment without real-life consequences (such as that found in a video game) and confronted with blocked progress, pain, or just basic desire?

I can tell you what I did.

Fail.

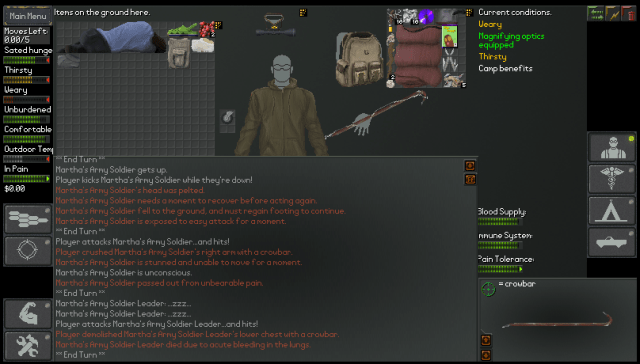

Pictured is the aftermath of an encounter with another survivor in NEO Scavenger.

I couldn’t stop. I drove my crowbar into his lungs for the last time…

I didn’t have to sleep with the married woman in Westerado: Double Barreled, or construct a voodoo doll in Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. I didn’t need to seduce a Struggling Artist’s Model or rob a drunken cavalry officer lying in a ditch in Fallen London. I didn’t have to pray to an Old God in Eldritch, or beat a man until his bones shattered and lungs burst in NEO Scavenger—consuming his body to stay alive for one more pitiful day.

But I did.

In some cases, I excused these actions in the name of ‘research.’ After all, if I’m going to tell others about Biblical and moral issues in titles, I have to go down the proverbial rabbit hole myself, right? In other cases, I wanted to test what a game would allow me to do. Can I use super-strength and a can of beans to turn a soldier’s head into a bloody pulp? Find a way to murder a family (of cannibals, it turns out) and still be seen as good?

What will the consequences (or rewards) be? And perhaps more importantly–does any of this actually matter when I can simply reverse my decisions by loading a previous save?

Pictured is Jack of Blades from the original Fable. He said I’d win a “special prize” if I murdered my friend in the arena for the pleasure of the crowd.

Guess what I did.

This line of thought was concerning enough, but when I found what horrible things I could do when my actions weren’t judged by a binary in-game good-or-evil morality system…That’s when I really began to question myself.

Why do I feel guilty, even after I go back and make the ‘right’ choice? Am I still a ‘good person,’ regardless of what I do or feel in-game? How evil is ‘too evil?’ What is wrong–for me? Is my perception changing with spiritual maturity and liberty…Or plummeting standards?

What if I’m compromised?

What if I’m not alone?

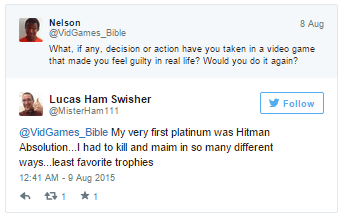

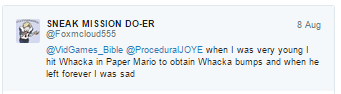

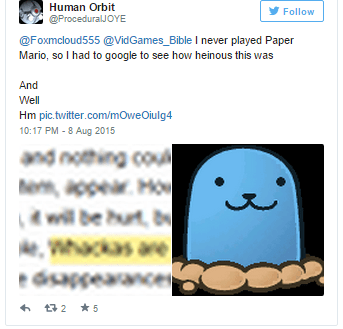

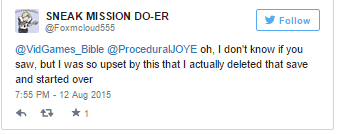

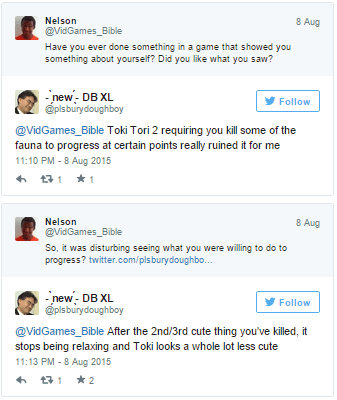

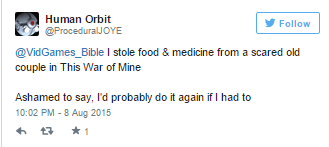

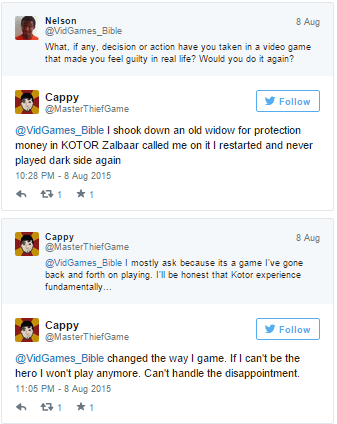

I took to Twitter (with the unexpected help of @ProceduralJOYE–many thanks) to ask if the games people played had ever affected them in real life. The responses were astounding.

Stories of feeling sick or guilty after murdering in-game characters, of restarting games whose length spans dozens of hours to change a single choice. It’s a testament to the power of video games as a medium–living proof that this so-called ‘disposable’ entertainment can make a serious difference, for good or ill.

And the saying, “It’s just a game?” It’s emblematic of a mindset that is willfully blind to these experiences.

It suggests that the actions we commit inside these virtual worlds–the decisions we physically choose to make, their consequences, and the resulting personal feelings they evoke–are meaningless. That we’re monkeys plinking time into a shiny box to escape the reality that we’re monkeys. That at the end of the day, there aren’t human beings with thoughts, consciences, and emotions behind every screen.

Anyone could look at an immoral act committed inside a video game such as murder or theft and say “That’s bad, so why don’t you stop playing?,” but that would be missing the point. I don’t personally care about shooting waves of mindless drones in Call of Duty orBattlefield. However, that man in NEO Scavenger?

I wanted him to die.

Interactions and gameplay systems are mechanical in nature, the resulting scenes shaped out of pieces of art and lines of code, consequences reversed with the load of a save, but their effects on our hearts and minds are undeniable.

In real life, I’m constantly afraid of giving a wrong impression and being seen as a bad person. I edit every tweet, examine and qualify every statement…Though I have genuine intentions, I exert so much effort appearing to be good that I end up “believing my own hype” and forget my basic, flawed humanity.

And then I play a game.

I see how callous, selfish, and petty I can be. I see myself. The part I hide from the world–that we all hide, to a certain extent. Pretending these sides of ourselves don’t exist is easier than confronting the darkness lurking at our collective core, revealed by the most unlikely of sources:

A Pixelated Mirror.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like