Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Did you know that games such as Project Gotham Racing and Ridge Racer 6 are paying Midway to include 'ghost mode' cars to race against, thanks to a patent in the company's 1989 arcade racer Hard Drivin'? We analyze the original patent, talk to Midway and licensee Global VR, and examine just how patents impact the biz.

If a patent is filed in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and no one is around to enforce it, does it make any money?

This somewhat zen query actually hides a serious business question about the best way to extract value from a patent. Sure, there's some prestige associated with publicly staking your claim to an idea before anyone else, but prestige doesn't pay the bills. It takes a significant investment of time and money to get a patent -- between 18 to 30 months and thousands of dollars in filing fees on average, according to PatentInfo.com. In the business world, the point of such investments is usually to make money.

In the video game world, there are two main ways to make money off a game-related patent. You can do it indirectly by using the threat of litigation to secure a monopoly on a lucrative genre or technology, holding the patent over the heads of potential competitors like a Sword of Damocles. Or you can be more active about it, bringing suits against infringers, usually resulting in favorable settlements from defendants unwilling or unable to defend their work.

But there's a much more direct way to make money from that moldy old patent – by renting it out in the form of license fees to other companies.

At least one company has been using this third method since at least 2001 to make money off a set of patents that traces its lineage back to a game from the late '80s. Look carefully at the legal fine print associated with games like Sony Online Entertainment's GripShift, Namco's Ridge Racer 6 and Sega's Outrun 2006: Coast 2 Coast and you'll find the following cryptic bit of legalese:

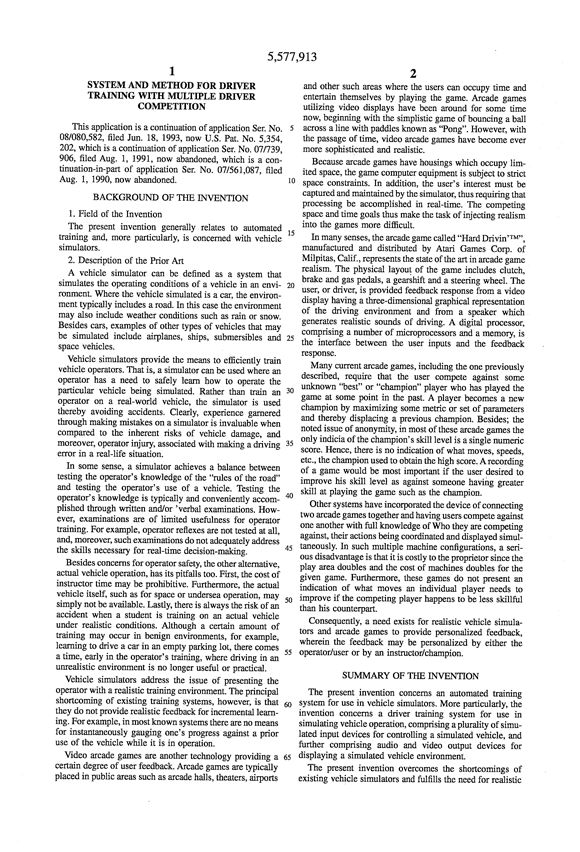

“US Patent Nos. 5,269,687; 5,354,202 and 5,577,913 used under license from Midway Games West Inc. All rights reserved.”

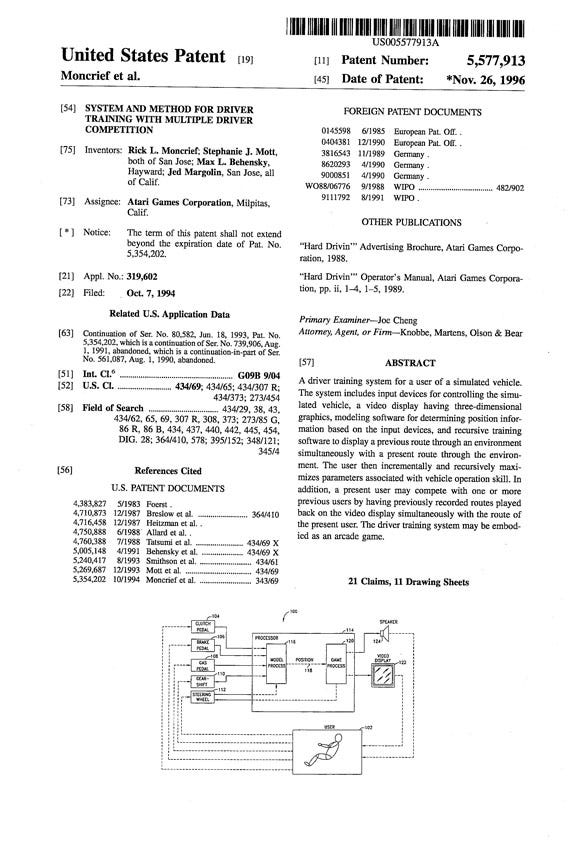

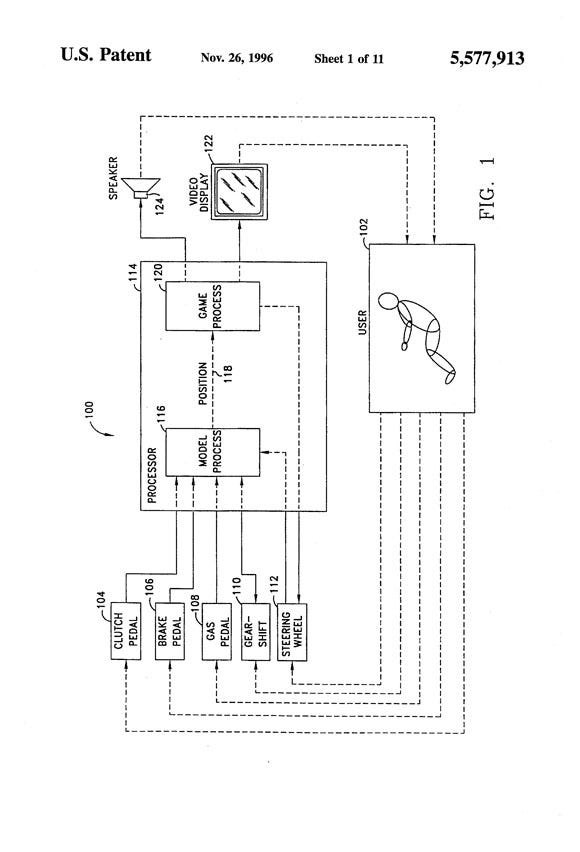

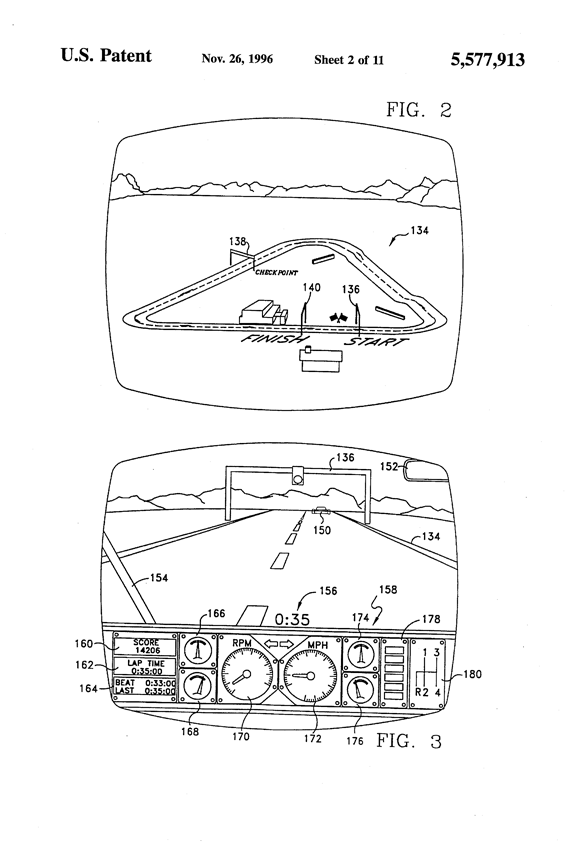

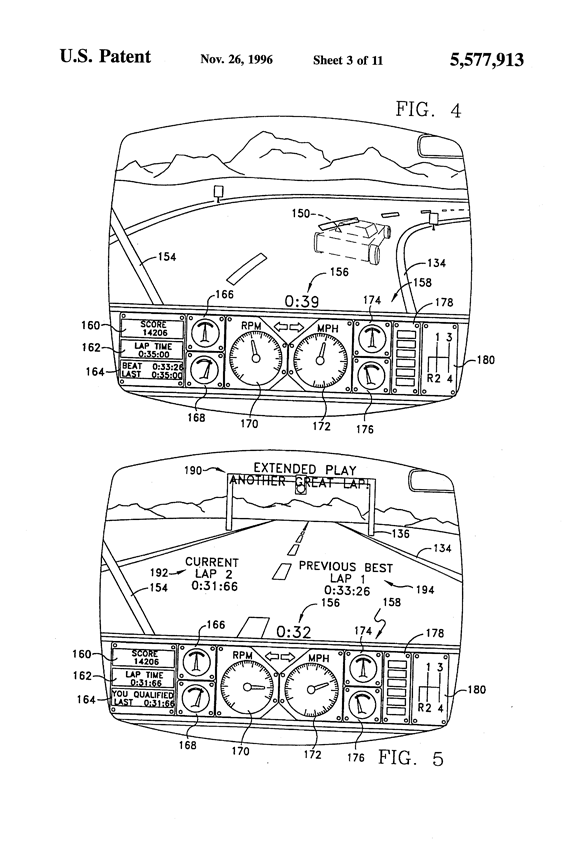

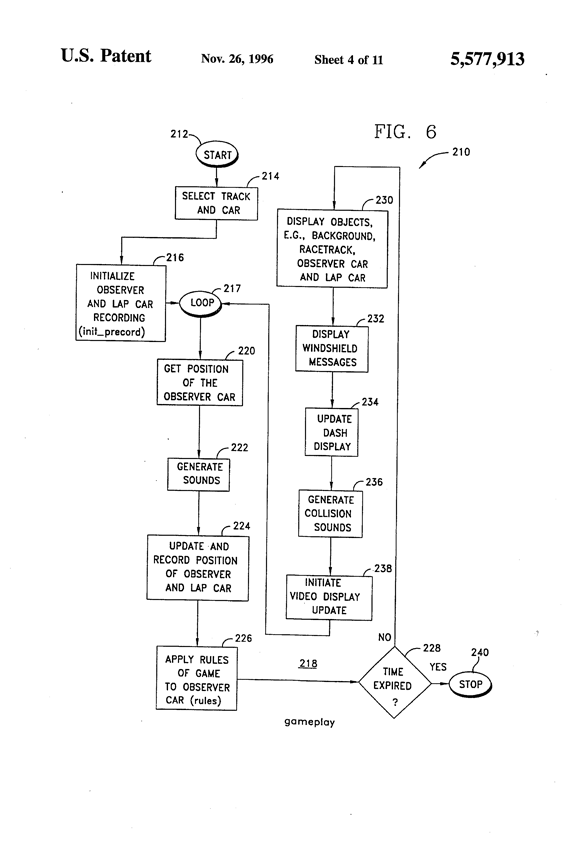

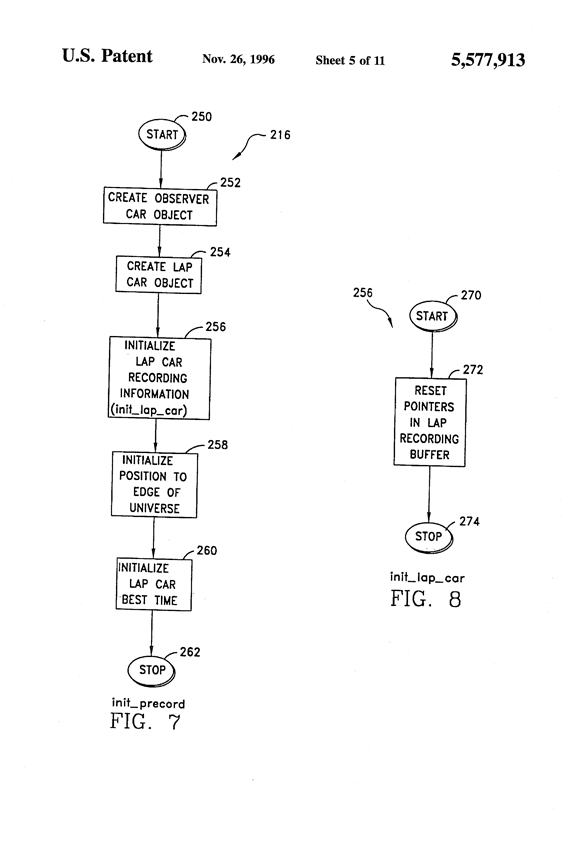

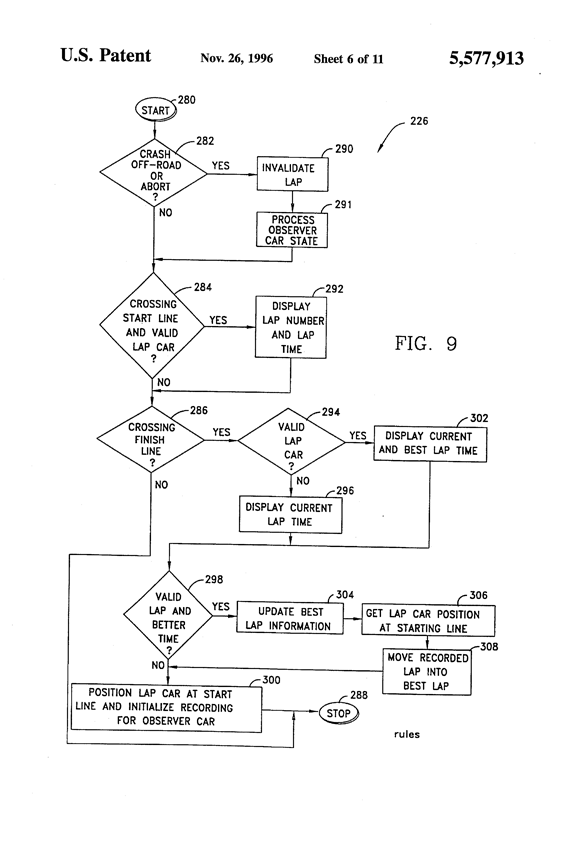

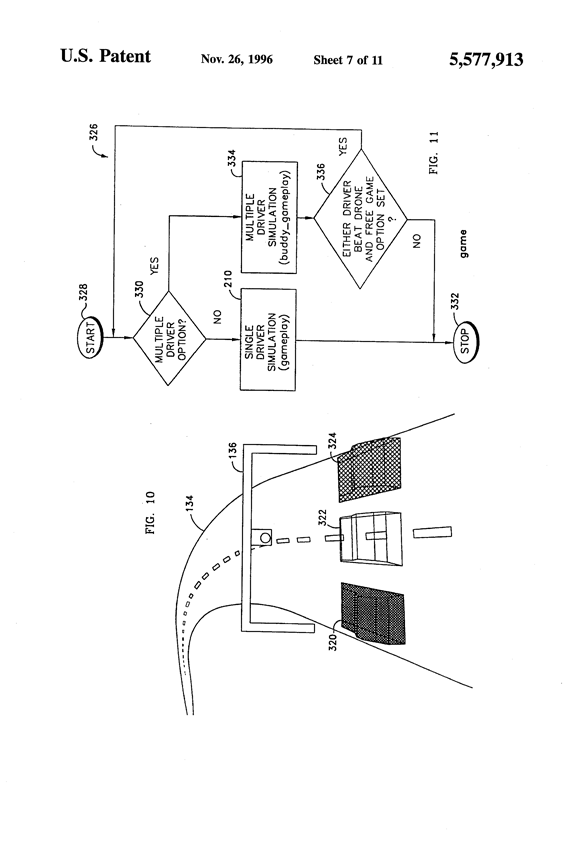

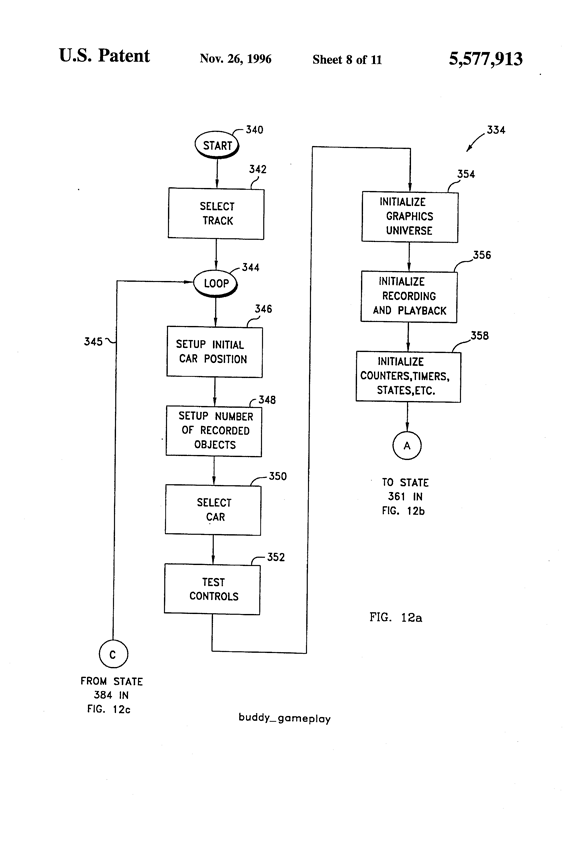

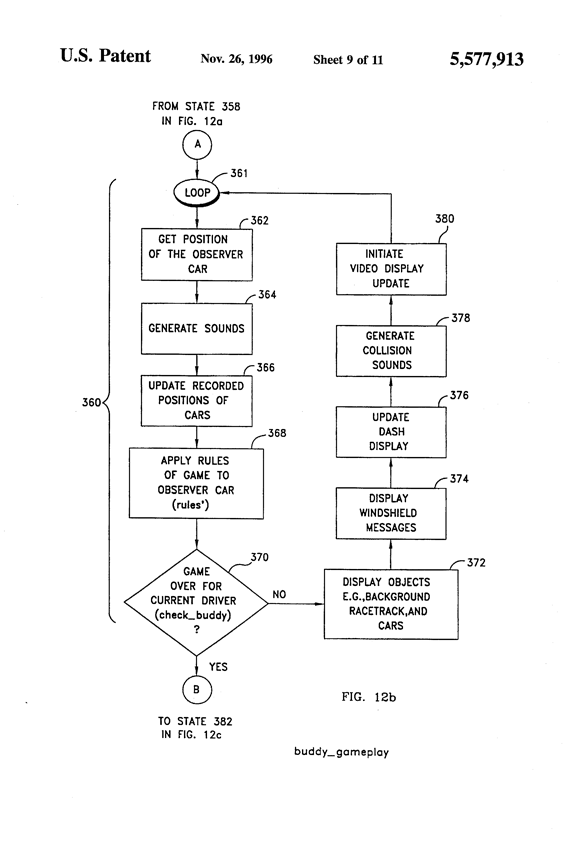

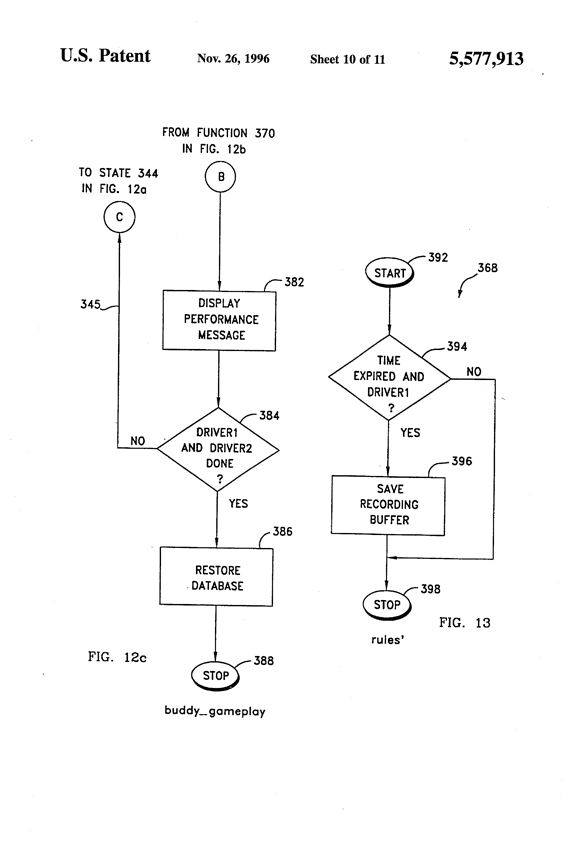

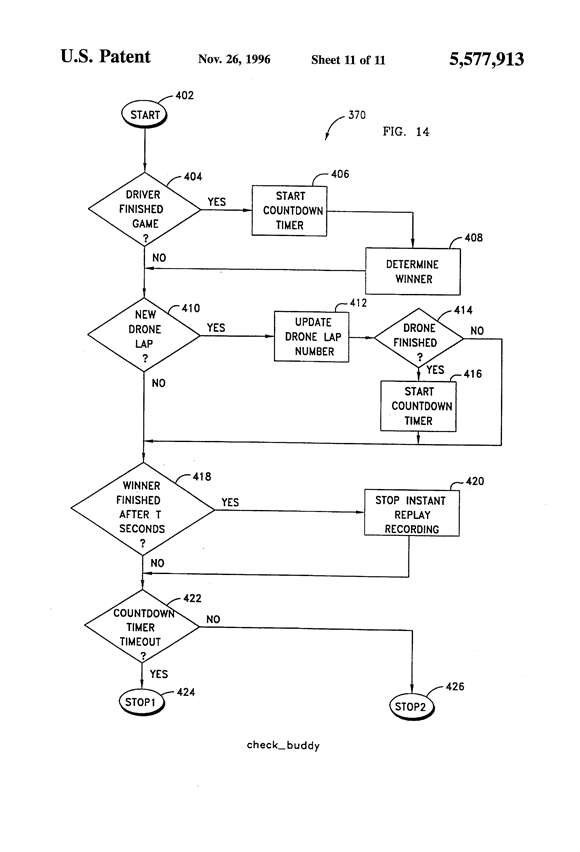

See if you can guess what these patents cover based on this easy-to-follow excerpt from patent '913.

“A first driver responsive software having a buffer, wherein the first driver responsive software is representative of a first user and responsive to said position information provided by the first user, and wherein the first driver responsive software stores in the buffer a first route of said simulated vehicle taken by the first user through said simulated environment, replays the first route on said video display, and stores at least one parameter indicative of a performance characteristic of the first route in the buffer; and

A second driver responsive software representative of a second user, wherein the second driver responsive software is responsive to said position information provided by the second user for a first time, and wherein the second driver responsive software displays a second route of said simulated vehicle taken by the second user through said simulated environment and determines at least one parameter indicative of a performance characteristic of the second route;

Wherein said first route is replayed simultaneously with said display of said second route on said video display; and

Wherein a best route through the simulated environment is selected by comparing route parameters indicative of the first and second routes.”

If you were able to condense this mouthful of a description down to “a ghost mode in a racing game,” you win a prize for succinctness that a patent lawyer could never dream of winning.

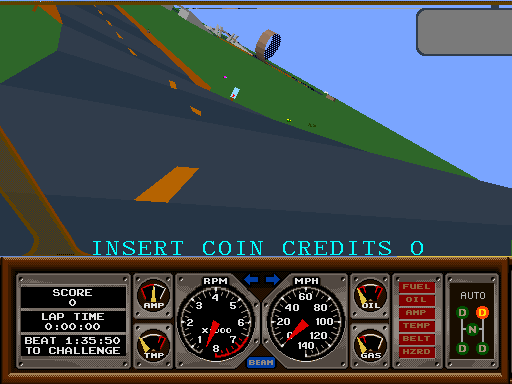

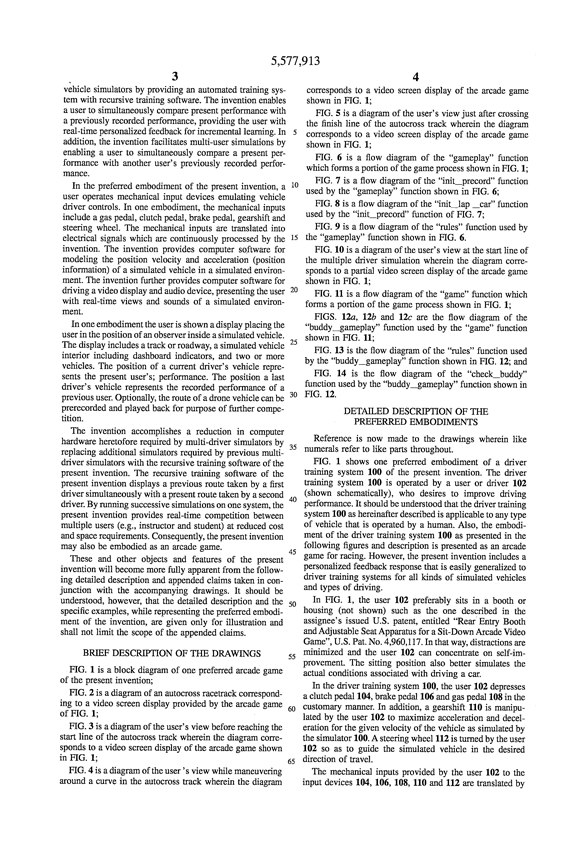

Classic arcade racing simulator Hard Drivin'

The patents Midway is licensing derive from the 1989 Atari Games arcade hit Hard Drivin', the first racing game to let players race against a translucent, ghost-like recording of their previous run. In 1993 and 1994, Hard Drivin' Project Manager Rick Moncrief and programmers Max Behensky and Stephanie Mott filed the patents cited above on behalf of Atari Games. The patents were all granted by 1996, just in time for Midway to buy up the remnants of Atari Games, including their patents, from Time Warner.

Midway spun the Atari Games division off into Midway Games West in 2000, and in 2002, the renamed company updated its claim by filing U.S. patent 6,755,654 for a “system and method of vehicle competition with enhanced ghosting features.”

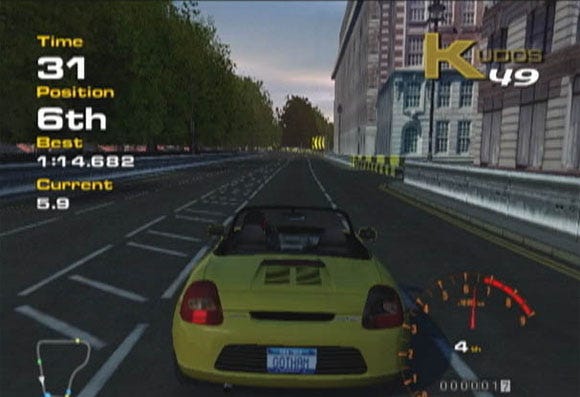

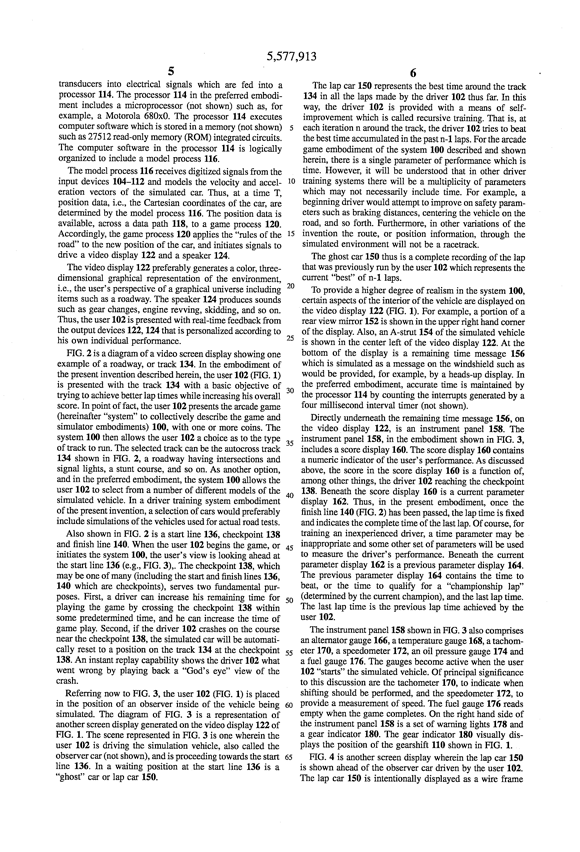

Microsoft's Xbox racer Project Gotham Racing

The updated patent was granted in June of 2004, though the licensing language for the older patents first appeared in the instruction booklet for Microsoft's Project Gotham Racing in 2001. Midway “currently has about a dozen or so licenses for its ghosting patents,” according to their legal team.

“It's more of a unique [patent] than other things I've seen,” said Debbie Minardi, vice president of corporate development at Global VR. Minardi acquired one of those dozen or so ghosting patent licenses for a “Shadow Attack” mode in the arcade version of Need for Speed: Underground.

While Minardi acknowledges that the ghost mode is more original than some of the “you've got to be kidding me” patents she's come across, she says it still probably doesn't deserve full legal protection. “If it was me I'd never have given them a patent on it,” she said. Taking that conviction to court, though, is another matter entirely. “Patents like these probably are easy enough to argue against, but it's expensive,” she said.

How expensive? A 2001 survey from the American Intellectual Property Law Association put the median cost of high-stakes patent cases at $1.5 million. And even if you can afford to defend your case to the end, there's a good chance you'll lose – a 2002 U.S. Dept. of Justice Special Report showed plaintiffs winning 59.3 percent of patent infringement cases and getting a median $2.3 million in damages for their trouble.

“Patents have a presumption of validity when they're issued from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office,” said Ross Dannenberg, an attorney at Banner & Witcoff and editor-in-Chief of PatentArcade.com. “In order to infringe a patent, someone has to perform every element of at least one claim. If you infringe just one claim, you infringe the patent.”

But that applies to patents for physical products and inventions. Can a patent on an abstract gameplay feature really hold up in court? It's hard to generalize, Dannenberg says, because such cases are pretty rare – coming to court roughly once every two years. What's more, most cases are settled out of court before a judgment can be rendered, making it hard to draw meaningful statistics from the available case law.

Most patent litigation hinges on the idea of obviousness – whether an idea is truly original or is just a simple, immediately apparent extension of prior art. It's a fine line, and one that game patents can easily fall on either side of. Magnavox's original patent on the Odyssey and the idea of Pong-style games has held up well in three different patent infringement lawsuits against companies including Mattel and Activision. But a loss in court can leave a company with a weaker patent, as happened in 1994 when Capcom failed to prove Data East's Fighter's History infringed on its Street Fighter franchise.

Most patent litigation hinges on the idea of obviousness – whether an idea is truly original or is just a simple, immediately apparent extension of prior art. It's a fine line, and one that game patents can easily fall on either side of. Magnavox's original patent on the Odyssey and the idea of Pong-style games has held up well in three different patent infringement lawsuits against companies including Mattel and Activision. But a loss in court can leave a company with a weaker patent, as happened in 1994 when Capcom failed to prove Data East's Fighter's History infringed on its Street Fighter franchise.

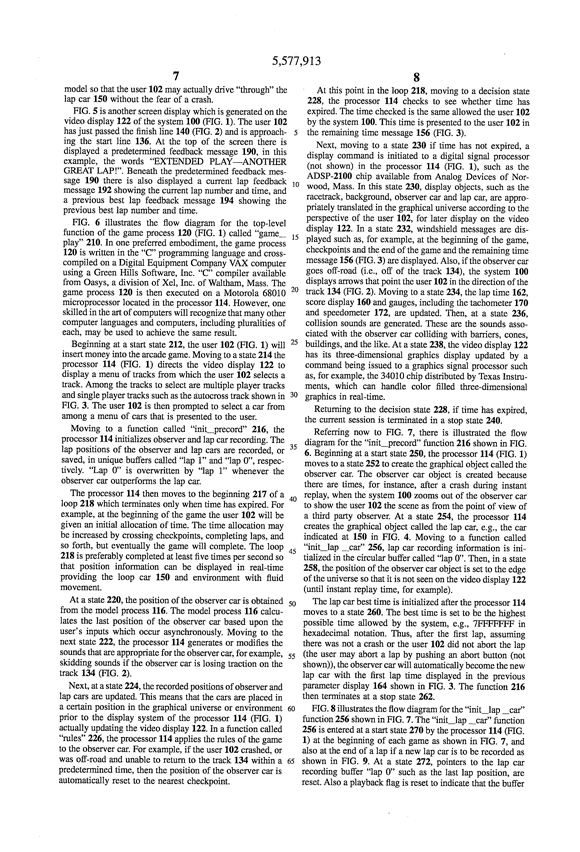

The Global VR team learned of Midway's ghost mode patents not through any legal threat, but through an ex-Atari employee who happened to be working on Need For Speed: Underground and remembered his old employer's claim on the idea. On the urging of the employee, who really wanted a ghost mode in the new game, Minardi and her team did a cost analysis to figure out how much the feature was worth and how many more units it would sell.

In the end, the value to Global VR ended up being almost exactly what Midway was charging for the license, an amount that Minardi described as “pretty reasonable.” Neither Midway nor any company we talked to for this story would comment on the exact price for such a license, but Dannenberg estimated it could run “anywhere from thousands of dollars to millions of dollars.” In other circumstances, Minardi said the team could have saved some money by tweaking the gameplay just enough to avoid infringement, but “instead of coming up with that creative approach, with a time crunch you do that cost analysis.”

Global VR's arcade racing title Need For Speed: Underground

What about companies that don't stumble across the patent on their own? Midway's legal team says the company “aggressively polices and protects its patent portfolio,” but a few games inevitably slip through the cracks. “I'm sure there's people infringing,” Minardi said of Global VR's own technology patents. “The question becomes: OK, do I have the time to go out there and find it.”

And when you do find the odd infringer? “What happens in most cases is people don't even know they're infringing,” Minardi said. “Anytime I've seen that stuff happen, people have been really good. People just want you to be aware of it.” And maybe make some money in the process.

[To help Gamasutra readers understand exactly what these 'ghost racer' patents look like, we've reprinted the original patent, granted in 1996, for #5,577,913, 'System And Method For Driver Training With Multiple Driver Competition' - the patent text is readable on the U.S. Patent office website, as are the other patents, #5,269,687; #5,354,202 and #6,755,654.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like