Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

We talk to Zach Barth about how making educational games has made him a better game designer, and why it's so hard to make educational games in the first place.

April 6, 2015

SpaceChem is a unique game in a lot of ways, not least because it manages to do a fairly successful job of translating the experience of programming from the obtuse to the engaging. It involves a lot of the same problem-solving skills, asking you to think up a creative solution to a problem that is usually initially baffling.

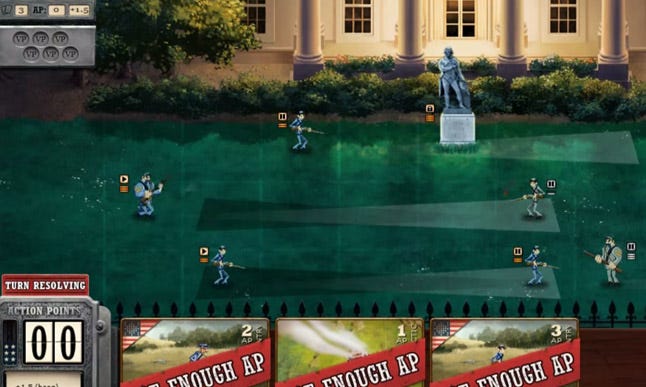

It was a bit of a surprise, then, when developer Zachtronics went a little bit dark after the release of SpaceChem. It was two years before its next commercial game, Ironclad Tactics, emerged, followed up more recently by Infinifactory, the 3D big brother of SpaceChem's programming puzzles.

In that two-year gap, Zachtronics spent its time making three educational games for a company called Amplify, taking subjects from its custom curriculum and extrapolating them out into a series of games.

With the educational market being so large, yet so impenetrable, I thought it would be interesting to find out what the experience was like for Zachtronics founder Zach Barth, and how it has influenced his approach to designing his subsequent commercial games -- as well as trying to figure out why it is so hard to make successful educational games, from both a commercial and educational perspective.

You’ve made both educational and commercial games now. What do you find is common across both of them?

Zach Barth: So one of the things that’s obvious with educational games is that you’re trying to teach something. And one of the things that’s not obvious about entertainment games is that you’re trying to teach something. You’re trying to teach them how to play the game.

We made SpaceChem and we didn’t know anything about making a game that was usable or easy to pick up, and it was kind of a failure in that regard, even if it was a success overall. Our tutorials are awful. They’re so bad.

So that was something we spent a lot of time reading about and thinking about, practicing: How to make better tutorial experiences, and not even "tutorials" in the traditional sense. To make it so that the game teaches you how to play the game by playing the game. And this is something that most triple-A studios have a pretty good grasp on, and the indie space, not always. But that’s something that we chose to make our specialty.

So when we decided to make educational games, a lot of that came in handy, because we’re making games about these subjects, and while we want them to learn how to play the game, we also want them to learn the subject matter. There is no "tutorial" and "not tutorial." It’s all tutorial.

And that really helped us understand how to make the game, and it’s flowed back and forth between our educational games and our entertainment games.

The other thing would be that with our educational games, it was about making a game that was fundamentally about the material, so that when you learn the game through good game design and good difficulty scaling, you also learn the material. You can’t help but learn the material if you learn the game. And that’s something that, again, is a design practice that works in both areas.

So do you find that that ends up with you? When you’re applying that back into your entertainment games like Ironclad Tactics or Infinifactory, are you forced to decide what your subject matter is?

"It’s almost now like our games are educational games about things that aren’t remotely realistic."

ZB: Yes, and that’s deliberate. Exactly. I’m kind of serious about subject material, and all that stuff. It’s almost now like our games are educational games about things that aren’t remotely realistic.

Having a really firm idea of what the world is that this game is supposedly a simulation of, and making sure that the game exudes those qualities. Ironclad Tactics had a lot of those qualities, because compared to SpaceChem and Infinifactory, which are a little more abstract, Ironclad Tactics was all about this historical event that absolutely did not happen, but in our world, did. So learning to take the sides and all the actors in that war and turning that into a game definitely required us to figure out that subject matter thoroughly.

There was a talk at PAX that was relevant to this, where someone was talking about board games, about how if you come up with all your story stuff, when you have a question about what your game needs, you can turn to the story and ask what the appropriate thing to our story would be.

It’s funny, because the typical German board games do the opposite, where they come up with abstract set of rules and then slap like a pirate theme onto it. You can feel the difference, though. That’s when people say, "Oh, this story isn’t relevant, because it’s clearly slapped on at the last minute," and with our stuff I want it to be the opposite, where it just exudes out of every pore that this is a real world trapped inside your computer.

And how did you end up making educational games in the first place?

ZB: After SpaceChem, we were contacted by a company now called Amplify. They’re owned by News Corp -- and they’re giant -- but before that they were called Wireless Generation and they made tools for teachers. So they got bought up by News Corp, and they were tasked with creating a tablet-based educational curriculum.

And one of the people on the team -- and it was a huge team, making a new curriculum from scratch and pushing it onto tablet -- and one of the small subdivisions of this team was a games team. The guy who was in charge of that had this really awesome vision, which was to get indie developers and get them to make educational games that are actually fun to play, stick them on the tablets, and then no one is ever going to tell the kids that they exist, or to play them. They’re just going to be there so the kids can discover these games and play them, and maybe learn something that crosses paths with their coursework, or maybe doesn’t.

"They want a game because games are fun, but they want it to teach all of their course curriculum which is never going to work."

So they went out and looked for developers, and one of their business people was a fan of SpaceChem, and contacted us, and we started talking to them. That was a couple of years ago, and we made three tablet games for them, and pushed out a bunch of updates, and it’s been a really great relationship because they really respect our creative freedom.

We actually had a lot of people -- after making the educational games, and after SpaceChem -- contact us about making educational games for them, but they already have too much of an idea of what they want. They want a game because games are fun, but they want it to teach all of their course curriculum, which is never going to work.

But the Amplify people were really smart, because they know you can’t really do that. So they let us pick the topics, and for one of our games, we started going down a path where there was no game to make there, so we changed our topic.

I mean, nobody’s going to let you do that! "Your topic is too hard, we’re going to make a different game." Most people would fire you for that, but they didn’t, and we ended up with a really great game as a result. Had we been forced to stick with the original curriculum goal, it wouldn’t have worked.

I imagine your games are successful as an educational tool, but did they do well commercially on the App Store?

ZB: They’re actually only available as part of the curriculum, currently. It’s sort of the disappointing part, because the world of schools is big and insane, and totally out of reach, so we don’t get a lot of feedback about how the games are being recieved. And even if we did, we wouldn’t be able to change anything, because there’s not that back-and-forth -- which is another reason Early Access is great, because we have that really intense connection with our players. But with educational games, and any kind of contract work, really, it’s hard to feel that connection.

More generally, it feels like "edutainment," as a genre, has been attempted a lot, but rarely successfully. After the Broderbund and The Learning Company stuff like Zoombinis and Carmen San Diego, there hasn't been much that's stood out. Why is it so rarely successful and effective?

ZB: Clearly, something has changed. Years ago we were playing all these educational games, like the ones you mentioned, and possibly this is part of it -- but they stuck us in front of computers with access to a bunch of games and just said "go for it," because they didn’t really know what to do. Kids are really smart with computers, because they’re good at figuring stuff out, so we just went and played games.

When I was in middle school we had a class where they let us play educational games instead. None of them were particularly tied to subjects, but they were about general stuff like puzzles and problem-solving, and they were really fun, and they were barely educational. They had some non-fiction aspects, where they were about real places, and there were puzzles, and they were about thinking.

It certainly felt like work, but it didn’t fit into a curriculum, and that’s one of the things working with Amplify, and how they’ve started focusing more on selling their curriculum, that’s become a bigger aspect of it, because that’s what schools want. Schools are being graded based on how well kids can take standardized tests, so that means they build these curricula that are wrapped around standardized tests, and so everything in the school day has to build towards that. That’s one of the big things.

And I really don’t know anything about education, but one of the things we learned making educational games is that teachers do not have enough classroom time. We can’t say, "Teachers, you have to use this game in your classroom," because that’s not going to work. Games are not an effective way of cramming a lot of information into a short amount of time.

"Schools are being graded based on how well kids can take standardized tests, and so everything in the school day has to build towards that."

First off, they have to be fun, so you have to choose to learn, and you just can’t guarantee that they’re going to get the information. That’s true of lecturing, too, but at least you’re trying, right?

I think there are so many things wrong with the educational system, like the obsession with curriculum, and the obsession with proving that people are learning. Some of my best learning experiences were in middle school -- where you’re growing as a person and having these things available that introduced me to vague topics like problem solving and how to learn. I feel like there’s a lot of stuff where making a game to fit to a curriculum that’s teaching you about fraction misses, and that’s certainly not the world that created those games that we remember fondly.

So you think the system changed, and the requirements changed, and that changed the games?

ZB: The requirements were added! There were no requirements before. There are two other reasons that I think they got away with so many educational games that weren’t based on specific curricular subjects. People knew that computers were the future, and Apple in particular did an amazing job of making sure that at every generation of technology, they convinced schools that they really, really needed to buy Apple hardware, and just in general that they really, really needed to buy computers. So it’s really easy to convince whoever supplies funding to your school district that you need to buy hardware, because hardware contains promises, and all software does is say, "it’s only about this."

So it’s easy to get money for hardware, and not easy to get money for software. But back then they really had nothing to run on the hardware they bought. And I guess all that was available was these few educational software titles, so people bought them.

There’s a reason we don’t make educational games on our own now. We did our work for Amplify, and it was great, but I would never try -- and I wanted to. Because I thought if we took what we were doing with SpaceChem and applied it to educational games, we could do something great. But once we found out what the market is like for educational games, that totally destroyed any hope of doing that.

Is it maybe that the educational games should be targeting parents over teachers?

ZB: No! How many copies are you going to sell when you’re targeting parents? Parents have no idea when it comes to video games. They have no idea what’s going on with their kids at school, and that’s not even necessarily what there should be games about. It’s hard enough selling games to the customers directly, selling it to parents… Oh, God. They don’t know what’s fun.

I’m just imagining some idyllic version where the parents educate themselves on the good games and then the kids play them in their free time.

"At one point I thought we were going to sell it, and offer a bulk discount, but the only bulk discount that works is free."

ZB: No. I mean, we actually give away SpaceChem for free to schools. At one point, I thought we were going to sell it, and offer a bulk discount, but the only bulk discount that works is free. And even then, it’s still...

It’s funny, we get a lot of homeschool teachers contacting us about that, and they all need free copies. But those guys aren’t really a school; they can purchase whatever they want. They don’t have a school district that has to approve it.

But still, educational materials are expensive, especially when there’s the question of how useful a single game is going to be. A good educational game should be tightly tailored to the material, which means it’s only going to cover a small amount of the curriculum. So you’re going to have to go shopping for all these stupid games all over the place, and it’s going to take your kids forever to play it, because it’s got all these grindy mechanics in it to make it fun, and they don’t have all that much educational density.

So our thing is that I’ve given up on making educational games for the most part, unless a really cool opportunity comes along. We’re totally open for something that completely changes the world of education, but the thing we’re doing now with this desire I have to make educational stuff, is to make all of our games secretly educational.

We make games like Infinifactory that aren’t full of grindy RPG bullshit, and it’s a game that’s about problem solving, and in its own way it’s a wholesome experience, as it’s not doing all these silly things to artificially inflate your ego; you’re really doing these things, you’re really solving problems. I really want to actually find a college that has an industrial engineering program and have them help us put together a curriculum on “Learn about Industrial Engineering with Infinfactory!”

I’m still on an educational games mailing list, because I still talk to some of the other developers who made games for Amplify, and they’re always talking about educational games, and how to Kickstart your educational game -- but I’m so glad to not have to label our game as educational. Because you know what? We’re going to sell so many more copies by having a game that’s not called educational, but is secretly educational. Just because we can sell straight to the people who actually want to play it, and find it appealing. And the educational qualities that somehow make their way in are strictly a value-add.

You May Also Like