Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

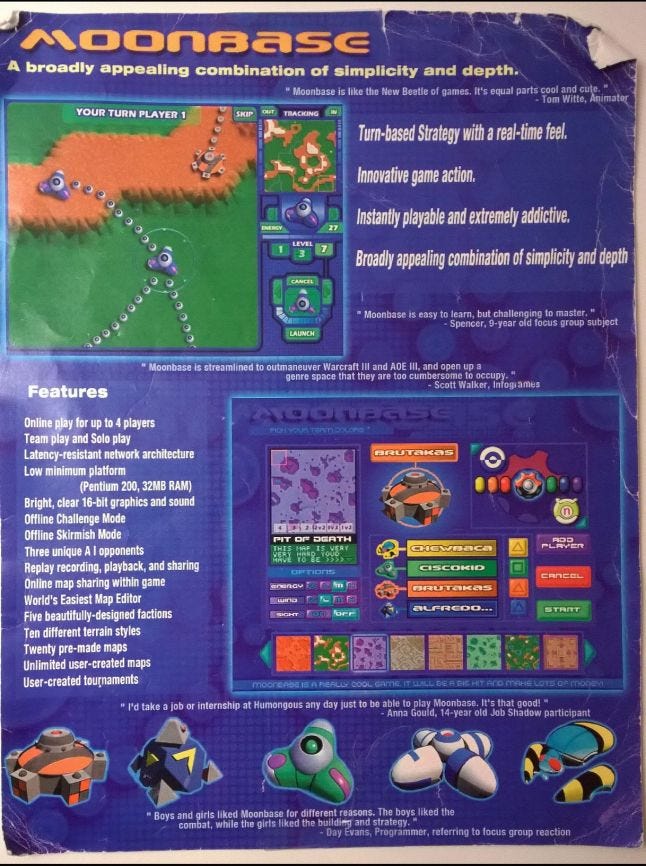

In 2002, Humongous Entertainment was a company known and beloved for its catalogue of popular tween-oriented adventure games. But its masterpiece was a turn-based strategy title you haven't heard of: "Moonbase Commander" - the best game you never played.

...Continued from Part 1 (of 3)

In 2002, Humongous Entertainment was a troubled company still beloved for its catalogue of popular tween-oriented adventure games. But its masterpiece was a turn-based strategy title that broke all of the rules: Moonbase Commander -- the best game you probably never played.

***

By the end of 2000’s summer, Moonbase was still a phantom project with a future as uncertain as our jobs. In over nine months, Rhett had not been given any assurances that his game would be released or even considered as a potential title. This was of minor consequence to him at that point and he told himself he'd be fine with a pyrrhic victory over none at all, just so long as he was allowed to see the project through to its end. To just finish the damn game.

“I just wanted to play it,” he says. “I wanted to try out this thing I’d had in my head for a while…”

Video games had always been in Rhett’s head, buzzing and fizzing and beeping like mad. Having come of age in the late 70s and early 80s, his was the generation that witnessed the vector-drawn dawn of the modern video game. Pong was his moon landing and Space Invaders, first contact. All across America kids were tossing quarters into upright televisions and sticking their faces twelve inches from the screen, exactly as adults had warned them not to. Naturally Rhett’s parents hoped to keep their son as far from this junk as possible.

Lucky for Rhett, they also had the good sense to know that computers were fast becoming an integral part of modern life. He was in his early teens when his parents bought him a Texas Instruments-99 and presented it with a single inexorable caveat: he was not allowed to buy or borrow games. Honoring his parent’s restrictions to the letter, he did what all needy wizards do. He conjured games from empty air—he made his own.

Cracking a tome teaching the rudiments of BASIC, teenage Rhett started by programming text-adventure games in the style of Zork and Planetfall. Within months he was ready to move on to bigger and deeper challenges:

“Eventually I managed to get my hands on a friend’s C64, and an early IBM PC,” he told me. And once he was able to teaching himself new and robust programing languages, his skills grew rapidly. “I wrote programs for sprite editors, paint programs, animation programs … and of course games. I was just having fun making and using all these programming projects in an attempt to emulate the games I wanted to play."

By the time he was sixteen he was a full-fledged vidiot—his brothers’ affectionate nom d’ordinateur—an all-in-one developer with a passion for games, digital music, and the breadth of knowledge to build them from scratch.

At eighteen he left home, enrolling in the Music Technology program at the University of Washington. But this didn’t last. He blames his lack of interest in higher education on his chronic hunger for video games, a passion which had resurfaced with a vengeance after he took a part-time job at an arcade-burger joint on The Ave, a bustling corridor of bars, thrift shops, and restaurants few blocks from UW's main campus.

“Between working there and spending hours on games like Street Fighter II, I didn't put in the time I needed to get all my coursework done. Eventually I made the realization that I wasn't at UW for the right reasons. So I dropped out.”

Despite his eagerness to make games for a living, it took him a further few years to find a job in the industry he had admired from afar for so long. When he finally made the leap in 1995, Humongous caught him first and put him to work on an early Putt-Putt title as a sound-effects programmer, a position that perfectly harnessed his unique spectrum of skills—coding, music, and games.

For the first time in his life, he was surrounded by well-adjusted adults who actually valued the output of all of his frivolous childhood experiments. One of those people was Ron Gilbert, who—at 31 years old—was already as near to industry royalty as we had in those days.

From the first weeks they worked together, Rhett was impressed by Gilbert’s unflagging dedication to the craft of making games and how he encouraged the same enthusiasm from each of his employees. “Ron did such a good job of shielding most of us from the business realities that we were free to simply make games.”

With Gilbert and his partner Shelly at the helm, Humongous Entertainment was an incubator of news ideas and appealing content. Success had come early and fast and the effect on the company was motivating. “There was a strong optimism there," Rhett remembers. "We were on the way up. The company had gone from under 30 people to around 60, and bigger things were just ahead…”

The late Bret Barrett was another inspiration. He was the first to introduce Rhett to LucasArts' beloved SCUMM engine and the endless variety it made possible. “This guy was, in my opinion, the heart of Humongous at the beginning. He was a talented programmer, and a very creative and positive problem solver. He believed in what we were doing in a supremely sincere and infectious way.”

Another point of pride was the creation of Cavedog Entertainment—the internal offshoot studio spearheaded by Chris Taylor. Chris had come to Ron with a robust prototype and a plan for a new real-time strategy IP in the mold of Warcraft 2. Ron took a look at their work, gave it a test run, and green-lit the project. Et voila—Total Annihilation was born. Two years later, in 1997, it was released to wide acclaim and impressive sales. This was an inspiration and a revelation to everyone at Humongous. The fact that Ron and Shelly had the confidence to muscle in on Blizzard’s domain for the sheer thrill of the endeavor was proof that a potent mix of optimism, skill, and dedication could, in the right environment, create avenues of limitless possibility.

As Rhett puts it: “This was just a case of Chris Taylor and [lead artist] Clayton Kauzlaric showing a bunch of initiative and perseverance and Ron being willing to take a risk on them. I was really impressed with the way those guys were able to follow-through with their vision for Total Annihilation. At the time, I was incubating a couple of simple arcade titles and I wondered if I had the stuff to make them someday…”

It would take Rhett almost five years to conjure that stuff and wrangle it into a fully fledged game. Until that then, his journeyman years were ripe with successes and setbacks. He listened, he learned, and he made mistakes. On one occasion—he recalls with embarrassment—he snuck an adult-themed easter egg into an Alpha build of a pre-teen Putt-Putt title, hardly thinking twice about its potential impact. When Ron pulled him aside a few days later to describe what his daughter had discovered while testing the game, Rhett’s stomach hit the floor. Gilbert spared his life with a stern warning.

It would take Rhett almost five years to conjure that stuff and wrangle it into a fully fledged game. Until that then, his journeyman years were ripe with successes and setbacks. He listened, he learned, and he made mistakes. On one occasion—he recalls with embarrassment—he snuck an adult-themed easter egg into an Alpha build of a pre-teen Putt-Putt title, hardly thinking twice about its potential impact. When Ron pulled him aside a few days later to describe what his daughter had discovered while testing the game, Rhett’s stomach hit the floor. Gilbert spared his life with a stern warning.

But these stumbles were few and far between. Piece by piece, Rhett was assimilating the best creative practices of a professional game designer. The experience of working under Ron and his coterie of talent had taught him the single most obvious but oddly overlooked rule of good game design—always put the player’s experience first.

"Ron really cared about how we designed and built these games. It mattered that young kids could pick up a Humongous game and start having fun without any instruction. Goals had to be clear, interactions simple and natural, user-interface minimal and uncluttered.”

This player-focused approach permeated every product that came out of Humongous in those first years. This was in keeping with the spirit of Ron’s first games with LucasArts. They had soul, style, and an inviting atmosphere. At Humongous this same honesty of spirit thrived.

“In many ways, this was the focus for most of my early time there,” Rhett says, before adding, “Until the business side of making games started to exert itself more. Then there was a shift from making great games, to making cheaper games, reusing assets, milking existing IP, avoiding risk…”

Whether this shift was deemed necessary due to market forces outside anyone’s control, or from mismanagement on someone’s part, or from an admixture of both, is outside the scope of this narrative. But it was clear to many that by the time Infogrames had taken charge at the turn of the millenium, the company’s priorities had shifted drastically. In the austere months of early 2000, the new bosses wanted familiar products made for cut-rate prices. If this meant sacrificing the originality of the games they offered, so be it. In the endless tussle between the Fast, the Cheap and the Good, the former two options were now leading the pack. As for Moonbase—Rhett was willing to sacrifice the Fast to make room for the Good. But the harsh realities of the current economic landscape were making him nervous and he had no idea how much time he had left on his clock. None of us did.

***

In August of 2000, on the recommendation of a former colleague who had jumped ship a few months earlier, I applied for an associate producer position at a smaller company called KnowWonder, a third-party developer in Totem Lake, Washington—one of Seattle’s most amorphous suburbs. Thanks to my colleague’s internal referral, I was hired within weeks.

That same afternoon I wrote up a brief letter of resignation and sent it to my supervisor and Humongous’s HR department. HR immediately scheduled an exit interview for the following week. On the day of the meeting, my HR rep asked me if there were any circumstances that would encourage me to stay aboard. I told her if Humongous could guarantee that Moonbase would be officially green-lit, properly staffed, and released intact I would be thrilled to stay and join the team. Nothing else at the company interested me. With so little experience, my boldness was totally unjustified. But I wanted to call attention to Rhett’s hard work and to make sure people were listening.

The woman interviewing me took down a few notes. She then asked me why I was leaving. Knowing no better, I told her I had found another job at another game company. Her inscrutable face stayed blank as she scribbled a few more notes. When she finished writing she transferred her papers into a folder and pushed it aside. Then she looked up and told me I would be leaving that afternoon.

“What about training?” I asked her. “Shouldn’t I train my replacement?”

Three hours later, hauling a backpack filled with a year’s worth of accumulated papers and trinkets, I bid goodbye to Humongous Entertainment and drove home.

My explicit support for Rhett’s clandestine project wasn’t the deciding factor in what happened next, but it was certainly emblematic of a growing sense that Humongous Entertainment was suffering from a severe case of ennui and that his game represented one of the only sparks of vitality in an otherwise moribund tomb. As rumors of Moonbase's genuine quality bounced around the office—and as more and more bored employees got their hands on it—it was inevitable that someone from the top would come knocking.

The hammer fell in the autumn of 2000 when Humongous's Vice President Andy Hieke wrote a cordial email to Rhett asking about the project. Andy seemed genuinely curious, a good sign. After a few chats and email exchanges, he suggested that Rhett show the game to a man named Jonathan Baron, a new producer recently hired off a stint at Electronic Arts. It would be Baron’s job to assess the quality and integrity of Moonbase and from there decide its future.

Rhett remembers those meetings with clarity: “At our initial meeting, my first impression of Jon was that he looked like the author Stephen King, but with a thick head of salty gray hair. He was affable, but also had an edge to his sense of humor, and was obviously a sharp guy. I didn’t know a ton of his history before we met (which included work on the Air Warrior and Ultima series), but the wisdom granted from all this experience was obvious during our first conversation.”

That wisdom—and the plain passion that sustained it—had an immediate effect on Rhett. Jon Baron was the first Infogrames emissary to convince him that his heart was in the right place and that he would assess Moonbase’s worth on its own merits and not according to some predetermined matrix of assumed profitability, brand viability, and market share. Baron simply wanted to know the basics: is it fun and can we sell it to the right people?

Their first meet-and-greet catalyzed the next stage of Moonbase’s unofficial development. “Jon guided me through all the stages necessary to formalize a full pitch for the game. Given how Ron had sheltered his designers from most of this when he ran Humongous, there was a lot of new stuff here. It wasn’t the cool, ‘fun’ part of making up a new game. It was the real nuts of bolts of building a game. It’s what I had asked for, so here I was.”

Day by day, one spreadsheet at a time, Rhett learned the arcane voodoo behind the business of game development—budgets, schedules, marketing strategies. This was a far cry from the lackadaisical days in his parent’s basement, where the only qualifications he needed were passion, perseverance, and time. But this old course had reached its viable limit in the real world. It was time to sacrifice a bit of his personal vision to get this game finished.

John and Rhett worked together for the next few weeks on a comprehensive assessment of the project in anticipation of a meeting with Andy. When they had something worth showing, they scheduled an official pitch.

“This is where things got weird,” Rhett says.

With Baron by his side, Rhett slipped into sales mode and gave Humongous Entertainment’s Vice President a full rundown of the game’s premise, its mechanics, its strategic depth and his hope for its future—the vision entire. When he finished, it was Andy’s turn to respond. Andy had some basic questions.

“He starting tugging at various aspects of the game,” Rhett remembers. On the whole, his overriding concern stemmed from his dislike of Moonbase’s setting. Andy found the cartoony retro-kitch of its moonbase units cold and uninviting. “Why does all this have to be on the moon?” Rhett recalls him asking.

In one sense, this can't have been too surprising. As the chief resident executive, it's clear that Andy was looking to steer the product to be more in-line with Humongous’s established catalogue. Kid friendly and parent approved. Warm and bright. Inoffensive. And yet, recognizing that Rhett had designed an underlying game system of some merit, he was generous enough to offer an alternative setting: What if the game had a “garden” theme? he suggested. Maybe your base is a flower patch or something. And your shields are domes of honey. And there are bees and hives and honeycombs…

Rhett was livid. In his mind, Moonbase was a package indivisible. Its mechanics and concepts had emerged directly from his affection for its lunar setting. They had guided and shaped the course of the game’s design. To suggest that Moonbase’s visual aesthetic was disposable was to treat the entire project as an amusing, one-size-fits-all prototype.

Before Andy could suggest pollen bombs and beekeepers, Rhett exploded in defensive tirade of profanity.

“Why a Moonbase?” he remembers shouting. “Because the moon is cool! Moonbases are cool! Spaceships are fucking cool! That’s why!”

Andy absorbed this abuse with aplomb as Baron tugged Rhett by the belt loops and pulled him down from the ceiling. Rhett cooled off and the conversation stabilized. Then, to his surprise, Andy gave him a tentative thumbs-up. Rhett was free to work exclusively on Moonbase until further notice. After a year and a half of effort, it was the first glimmer of hope that his game might see the shelves. Rhett didn’t know what else to do but thank him. Andy said he’d have a think on the situation and shooed the pair from his office.

In retrospect, Andy’s objection to Moonbase’s visual aesthetic was likely some of the safest criticism Rhett could have heard. A general re-skin wouldn’t necessarily damage the core gameplay experience, since games of Moonbase’s nature—competitive and rule-based—are remarkably resistant to superficial visual tweaks. But Rhett’s instincts had kicked in hard at Andy's off-the-cuff suggestion. If he compromised his vision too easily and early, he felt he might loose his grip on the project entirely.

Back in the hall, Baron scolded Rhett for losing his cool but conceded that the meeting had gone well. Rhett was grateful. The first of his major hurdles had been cleared. Better still—despite Andy’s suggestion to soften the game’s look and feel—the general premise of Moonbase had won him over. No small feat. A new IP was coming to life.

***

It was Bruno Bonnell—Infogrames’ CEO and Humongous Entertainment’s absentee landlord—who initiated the next stage in the effort to put a man on the Moonbase. In the early spring of 2001, mere months before the big lay-offs, Rhett got the news that he would be pitching his game to Bruno in Los Angeles where the big boss would be wrapping up some company business. In earlier times a designer could wander down the hall to Ron Gilbert's office with a burned CD-ROM and a solid idea. But those days of sliding into success on elbow grease were long gone. The new reality was multinational conglomerates, parent companies, and boards of directors stacked with men and women from all walks of life, many of whom couldn’t pick Pac-Man out of a police line-up.

Rhett was terrified by the idea of pitching directly to Bruno. But with Jon Baron backing him up he was willing to try. They discussed the format for a few days before Rhett proposed a winner.

“Dissatisfied by how much I could demonstrate using only PowerPoint,” he says “I built a presentation inside the Moonbase engine. This allowed me to show segments of gameplay, complete with overlays for key points so I could pitch over the top of a live, in-engine replay of the game.”

In other words, a demo that made the case for its own existence. It was clever and cute and a hell of a lot of work. Rhett worked overtime to make it happen, but the effort paid off. Baron was impressed. When everything was running smoothly they fixed a meeting with Bonnell—the final week of May, 2001.

“The night before my flight,” Rhett admits, “I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I was seriously stressed out. I had never been in this kind of moment before—where the fate of something I’d been working on for years was about to come down to a single meeting.”

Rhett arrived at LAX in the sun-bleached hours of morning. A hired driver greeted him with a placard bearing his name and Infogrames in large handwritten letters. Rhett introduced himself and followed the man to his limo. An hour later they pulled up to the Paradise Pier Hotel in Anaheim. When Rhett understood exactly where he was, he laughed. Bruno had come all the way from Paris to stay at Disneyland.

Rhett slid from the cab and marched past the hotel’s valets. He could hear the rumble of amusement machinery and the squealing of children bouncing in from the park a stone’s-throw away. Once in the lobby he made a few inquiries and was directed to a conference room. He trundled upstairs, found the right door, and knocked.

“As I was led in, there was a striking contrast to what I had just experienced outside. It was dark and deathly quiet. I noticed all these spreadsheets on all the computers in the room and recognized several executives from all over the company. That’s when I realized that I’d been invited to pitch during a budget session. These folks weren't there to listen to a pitch for a new IP. They were there to fight for enough funding to keep their studios open!”

His nerves alight, Rhett passed around a stack of Moonbase info sheets he'd made specifically for this audience and then loaded up the demo. He played through his presentation at a snail's pace, gradually letting the room absorb it. When he finished, he opened the floor to questions. On instinct, his eyes drifted to Bruno. The CEO—looking like a stouter version of the philosopher Michel Foucault with his framed glasses and shaved, cue-ball pate—bobbed his chin up and down, clearly working something through in his head. He didn’t hate the game, that much was clear. But he wasn't showing his hand either. At last he said, simply…

His nerves alight, Rhett passed around a stack of Moonbase info sheets he'd made specifically for this audience and then loaded up the demo. He played through his presentation at a snail's pace, gradually letting the room absorb it. When he finished, he opened the floor to questions. On instinct, his eyes drifted to Bruno. The CEO—looking like a stouter version of the philosopher Michel Foucault with his framed glasses and shaved, cue-ball pate—bobbed his chin up and down, clearly working something through in his head. He didn’t hate the game, that much was clear. But he wasn't showing his hand either. At last he said, simply…

“Okay, you shoot, you hit. You shoot, you miss. But where is the strategy?”

Rhett was incredulous. The strategy? It was all right here! Turn management, the cost-versus-risk of spending energy to deploy units, the geographic placement of hubs, the scarcity of resources, and on and on. To Rhett, the strategic variety of Moonbase was self-evident. He had walked into that room expecting more grumbling along aesthetic lines and wondering if the execs would demand a circus-theme, or an offshoot of the Putt-Putt franchise, or maybe Andy’s beehives. But to fundamentally miss the game’s single obvious strength…

Before Rhett could respond, an executive from recently-acquired Atari chimed in: “Bruno, I think there’s something here. This is really original. There may be depth that’s not obvious.” Rhett nodded vigorously, shifting on his aching feet. Then another exec put a risk-versus-reward spin on the project. “The placeholder art isn’t too bad. This thing could practically be shipped as is…’

Rhett’s stomach lurched at the suggestion. It married a dram of healthy confidence in the property with the ruthless efficiency of a company man trying to save a few thousand bucks.

“Sure, I was grateful for the compliment to my programmer art,” Rhett says. “But I was more mortified that shipping it as-is was something they’d consider. This suggestion underestimated the impact that talented artists would have on the project.”

Polite discussion continued for another few minutes until it was clear some of the execs were desperate to move on to more pressing business. Bruno thanked Rhett for his time and sent him out the door with an inconclusive promise: “We’ll investigate further.”

Rhett thanked everyone and made his way to the lobby. Then it was straight back to LAX. By late evening he was back in Seattle and fretting about his future.

***

Two weeks later, on the 14th of June 2001 at the Embassy Suites Hotel in Lynnwood Washington, approximately one-hundred Humongous employees were fired en masse. Rhett was not among them.

He was shocked at the callousness of the move, of course. The facade of an offsite meeting, the cruel sorting scheme, the aloofness of the whole procedure. And as he sat there in the Mount Rainer conference room listening to a brief description of the fate of his fellow employees in Mount Baker, he couldn’t help but wonder if one of the laptop screens he had seen just weeks before in that conference room outside Disneyland had contained vital clues to what was happening now.

In the hours and days that followed, Rhett said goodbye to old colleagues and friends. Then he returned to work. Companywide, the layoffs had decimated employee confidence, dragging morale to its lowest point ever. But Rhett’s buzz hadn’t been killed entirely. Only days before, he had learned exactly what Bruno’s call for further investigation meant: consumer market testing for Moonbase. This was positive news. It meant Infogrames was willing to give his game a fair hearing as a potentially viable product.

But Rhett had major reservations about the process: “We were getting piggy-backed on the end of a test for a potential new Humongous-style adventure game character.”

This was far from ideal. Since day-one Rhett had conceived and designed Moonbase as a game for teenagers and young adults—something to catch the attention of blossoming gamers. Kids growing out of interactive storybook tales and into the world of competitive games. But this wasn’t the audience the marketing team would provide. They’d bring their usual posse of 8 to 12 year olds, ask them some questions about their gaming habits, and show them a few slides of art concepts. Then it was out the door with lollypops and gift certificates. End of story.

“Knowing what I do now,” Rhett says “This was probably a no-win situation for the game. Had the game failed with this group, it would’ve been canned. Succeed, and it would get pigeon-holed as belonging to this group—the tweens.”

All reservations aside, Rhett wanted the game to flourish in some fashion, whether lavishly escorted out the door or rudely kicked to the curb. He had come too far to surrender on a technicality.

On the day of the test, Rhett steeled himself, ambled down to the marketing department, and pushed into the monitoring room. Beyond its clammy darkness an amber pane of one-way glass gave a shaded view of the ongoing test. On its far side a single adult guided a dozen fidgeting children through a carefully parsed set of questions illustrated by a few muddled screenshots. That’s it. No demo of the game itself, no captured movies. Just questions and concept art. Rhett scanned the captive audience. The kids were zombies, yawning and squirming and knuckling their droopy eyelids.

“These kids were bored!” Rhett says. “As in can’t-sit-in-my-chair-sprawl-out-on-the-floor bored…”

Left there, the test might have crushed Moonbase into vaporware. But marketing had made a fortunate concession that day. Moonbase wasn’t a game in a genre they weren't familiar with and they took the unusual step of letting Rhett guide a second round of tests himself. Knowing this beforehand, Rhett had once again come prepared. He had brought another demo.

“When it was my turn, I walked in and asked, Who wants to play a game where you launch bombs to blow up enemies on the moon? And the little buggers lost their shit!”

After personally leading the kids through a specially prepped presentation, Rhett walked out of the room feeling good. He’d gotten exactly the result he wanted—laugher and cheers. Marketing, however, had not. And Rhett knew it.

“To be clear," he says, "I broke all the rules of a properly run focus test. I was not an impartial presenter. I showed them exactly how to play while explaining how cool the game was. I put myself in the mode of 12 year-old me. I gushed about all the stuff in the game like I would’ve done on the school playground. And it worked…”

Miraculously, Rhett’s interference didn’t totally invalidate the playtest results. Someone somewhere wrote up an encouraging report and forwarded it to someone else, who in their turn approved the money for a proper product analysis using an independent marketing company.

But this only gave Rhett additional cause for worry. “The response from this next group was that Moonbase should be centered in a 'tween to teen' group. At the time, the teen part seemed like a major victory to me. Humongous had never targeted users that old with any previous offerings. Unfortunately, as we would later discover, they saw tween as not just the bulls-eye, but pretty much the extent of the game’s reach.”

This knocked Rhett’s hope down a few pegs. The game he had designed specifically to lengthen Humongous Entertainment’s reach was about to have its arms amputated. And yet the overriding message from the research group seemed optimistic: we can sell this thing. And that was enough for Bruno and Andy.

Within days of reading the marketing analysis breakdown, Rhett got the email he’d been coveting for two years. Moonbase was a go, a greenlit project, albeit with an alternate title suggested by someone in marketing.

Enter, Moonbase Commander.

Continues in Part 3 (of 3)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like