Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

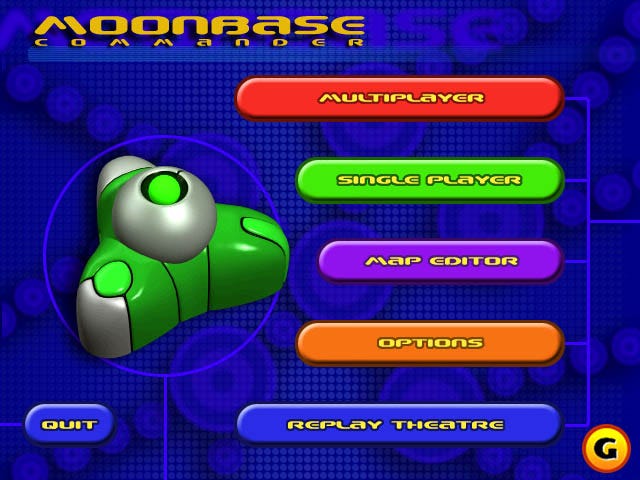

In 2002, Humongous Entertainment was a company known and beloved for its catalogue of popular tween-oriented adventure games. But its masterpiece was a turn-based strategy title you haven't heard of: "Moonbase Commander" - the best game you never played.

...Continued from Part 2 (of 3).

In 2002, Humongous Entertainment was a troubled company still beloved for its catalogue of popular tween-oriented adventure games. But its masterpiece was a turn-based strategy title that broke all of the rules: Moonbase Commander -- the best game you probably never played.

***

In the torturous process of game development, days of confidence and rapture can be few and far between, sandwiched between moments of confusion, doubt, and heartache—all this when things are going smoothly. When the road is rough—say, when your publisher seems to have an active distaste for the products they are pushing—the insanity piles on fast.

Rhett remembers one day in particular that left him with a painful understanding of his employer’s apparent psychosis. It was late April of 2002—many months before Moonbase Commander was scheduled to hit shelves—when one of Humongous's top executives called all senior Leads down to the lunchroom for an impromptu pep talk.

“He had something to show us,” Rhett remembers with some amusement. “Something inspirational. He had seen a game that he felt signaled the future of Humongous Entertainment. A signpost for what we could do, what we could be.”

Rhett couldn't imagine what sort of personal revelation the exec might have had at this point in his tenure. Humongous was already running on fumes with an exhausted workforce. Any major shift in direction without an equivalent shift in management priorities would likely destroy them.

When Rhett reached the lunchroom, the guy was already there, pacing slightly at the head of a small crowd. A large screen had been erected at its far end. This had all the makings of a proper presentation. When the room was full, the exec stepped forward. He had a peppy look, animated and alive. He pointed to the screen.

“This is what we want from this company,” he said. “This is the sort of thing Humongous should be making.”

The lights dropped and the screen lit up with the familiar grey glow of an empty signal. For a painful few seconds nothing happened. People shuffled in their seats. Then, up popped a familiar logo. Squaresoft.

“It was Kingdom Hearts,” Rhett says. “A game made in partnership with Disney. He played us the animated intro and stood back and gleefully took it in. We all watched this, our intrigue turning to bewilderment as this elaborate opening cutscene played out. Most of us recognized that the cost of a typical Squaresoft cinematic was probably higher than most of our entire new game budgets!”

When the opening movie ended, the exec ordered the lights back on. The room was quiet. The exec seemed to flinch, like he’d just been slapped by total silence. Perhaps he had expected a round of applause, or a shout of Captain, my Captain. But he got nothing.

“What’s wrong with you guys?” he moaned,“This is exciting!”

Nobody could argue with that. Kingdom Hearts was exciting, absolutely. Released weeks earlier, it had instantly established itself as the gold-standard for licensed-property videogame adaptations. Beautiful, fun, and critically acclaimed. It was also the sort of project that Humongous—in its current gimped incarnation—was wholly incapable of making.

“I don’t think [this guy] really grasped the amount of content required to build out a world like that,” Rhett says, “And it was clear that I wasn’t the only one doing this math. The faces around me were slack, defeated, dejected. We’d been laboring to make $1m games for just $500k for almost a year. And now he was showing us a game that most likely cost $10 million, and suggesting that we just do the same.”

Hounded by a gathering sense of hopelessness, Rhett returned to his desk and dove back into Moonbase Commander. What the bosses had intended as a pep-talk had only given their employees more reason to sputter and fume. “It was heartbreaking,” Rhett admits. “We did have the talent to do something like Kingdom Hearts, definitely. There were people at Humongous Entertainment who once even had the desire to do it. But it was abundantly clear to all of us, that there would never be a budget for it.”

Nor was there the political or creative will. As Moonbase Commander’s release date crept ever closer, more consumer test reports began to trickle in, each one an accruing cause for worry. In addition to the title's name change—a standard tweak Rhett had no objections to—Infogrames’ top brass had also skewed its projected audience southwards and they were now asking him to finish the game on a budget of $300,000, a number that did not fill him with much hope.

“It was disappointing, frankly. Not just because it wouldn’t realistically fund the quality of game I wanted, but because it showed a real lack of commitment on Infogrames’ part.”

Ever the fighter, Rhett pushed back:

“I told Andy directly, You know it’s going to end up costing more than that, right? At least twice as much.”

Andy responded with a modest measure of diplomacy. He said, simply, that cost wasn’t something he needed to think about at that moment. This implied an unofficial degree of leeway. How much leeway he wasn’t willing to say, but this was just enough for Rhett.

“So we had a deal, at least on the production side. Their lack of commitment bothered me, but I still hoped that once the game was ready, they’d all see how great it was and get behind it. But it order to do that, we’d need to build the team that would take this huge prototype project and turn it into a finished title…”

It was time to put this thing in a box.

***

By the autumn of 2001, full production on Moonbase Commander was finally underway. Within weeks of its official green light the team swelled to well over a dozen eager devs and the game saw rapid improvements almost instantly—all the tweaks and tucks that Rhett had ever hoped for.

“I would describe our production as dense, intense, efficient, and rapid. We had a ‘working’ game, which reduced a lot of risk. But we had a lot of pieces that needed to be completed by a fairly small team in a scant few months … and it took the formidable efforts of Pat Wylie to manage this production. [He] made sure that everything moved along internally, and handled all the other stuff necessary to get this thing out the door.”Working closely with Pat, Rhett now had to make some hard and fast decisions. Overhauling the game’s graphics engine was an early priority, a task eventually overseen by Brad P. Taylor, who set to work optimizing SCUMM’s sprite renderer to accommodate the game’s quasi-3D look. At the same time, engineer Daryl Mlinar took a stab at the enemy AI. Until recently, Moonbase had been a multiplayer game primarily, with rudimentary computer opponents to fill out multiplayer battles. It was Daryl’s task to endow each of the four enemy factions with identifiable personas, complete with unique tactics and quirks.

With these basic gameplay tweaks underway, artist Cisco Martinez updated the look and feel of Rhett’s serviceable programmer art with concepts that solidified the game’s theme and tone. The result was a retro-kitch paint job with a distinctly 70s Sci-Fi feel—vibrant colors, chunky minimalist terrain, and kooky units worthy of films like Logan’s Run or early Battlestar Galactica. Once these concepts had been approved, texture artist Mark Lautenbach and modellers Dan Cole and Jim Millar brought them life.

Behind the scenes, coders Kristen Hebenstreit and Ben Young refactored the UI and menus, while the testing team—Pat Hoynes, Steve Kuo, Jeff McCrory, and Robert Ochs and Chad Verall—also contributed the vast majority of the game’s multiplayer maps. As Moonbase Commander’s best and most experienced players, they knew the recipe for what made a great layout. Rhett’s intuitive map editor made it a cinch to put this knowledge into practice.

As everything came together, Humongous’s Game Director, Brad Carlton came aboard as a writer for a short time to add personality to the game’s four warring factions. “If you've ever chuckled at any of the dialog in Moonbase Commander,” Rhett says, “You can thank Brad for that.”

Work thundered through the winter and into the spring of 2002 at a pace that astonished everyone, including Rhett. Around this time the team got word that Infogrames was shooting for a release in the summer of that year. This was a more generous schedule than Rhett had anticipated and he was grateful for the support and apparent confidence.

This convenient date also meant that Humongous would have a chance to unveil the game to North American press at E3 in early June, a critical opportunity for a new IP with zero industry buzz. But with the popularity of sci-fi themed strategy games at an all-time high, Moonbase Commander seemed perfectly positioned to make a splash. The timing couldn’t have been better. By the time the exposition’s doors opened, the game would be all but finished, obviating the need for a tailored demo or a fancy presentation. If marketing and PR could get a few dozen journalists to play it for just 15 minutes, Rhett was confident they’d find their audience.

But Infogrames had other plans. Empty, incomprehensible plans. When Rhett saw a complete draft of their final E3 lineup, Moonbase Commander wasn’t on it. They weren’t showing the game to anyone, anywhere—a finished title that would hit the shelves in less than two months.

“I suppose it was a pretty clear message,” Rhett says. “Either Infogrames didn’t know what to do with the game, or that they didn’t intend to do much…”

He was gobsmacked, but he wasn’t going to let this slight kneecap his game’s chances in its final lap. As he had done so often in previous years, Rhett took matters into his own hands. He contacted a colleague named Pat Hoynes, a level designer from Humongous who had been tapped to demo upcoming titles at E3, and provided him with a copy of Moonbase Commander’s most recent built. Pat had already worked as a level designer on Moonbase for the past year and like most of its alumni had a keen sense of loyalty to the underdog project. Rhett’s only directive to Pat was simple—show it to anyone you can.

Unfortunately, Pat’s booth duties kept him busy for most of the show. But on day three, as the crowds were thinning, Pat pulled aside Penny Arcade’s Tycho and gave him a quick preview. They played a couple matches and Tycho left impressed. That’s the story Pat forwarded to Rhett that night, who was happy to hear it and hoped for the best.

A few days later, Tycho wrote about the experience on Penny Arcade : “The [Infogrames booth] is dead, it’s not like anybody is going to see it when Backyard Hockey gets closed down, and some new game—a game called Moonbase Commander—pops up in its place. As soon as I see it, I’m snared. I mean, I have to look at it for about ten seconds before I understand the entire concept. At about the thirtieth second I’m starting to understand the ramifications of those concepts. And somewhere about a minute I want to stick a pen through the man’s temple and clutch the keyboard to my breast…”

Rhett was touched by Tycho’s gonzo praise. It was the first time anyone unaffiliated with Humongous had been able to play the game and by all accounts it was weaving its intended magic. But even Tycho understood the hurdles stacked before this odd-duck title, and he sketched them clearly:

“If the game gets pushed as a Strategy-Game-With-Training-Wheels, so be it, but that’s a mischaracterization. What it actually is is some kind of holy-fucking-grail. Accessible, yet possessed of tactical wealth. It’s a challenge, though, and I recognize the quandary—how do you promote something that is such a simple pleasure, without making it sound simplistic, designed for children, or for idiots who can’t somehow grapple a ‘real’ game?”

Back in Seattle, Rhett was wrestling with the same conundrum and losing sleep as a result. As the game’s release date crept ever-closer, his hopes plummeted as he saw more and more signs of Infogrames’ total lack of interest in the property. Marketing seemed wholly uninterested in getting a clear message to the right people: “The box art and text were designed for 3rd graders [and] ads were planned for parenting magazines, written for the parents of small children. We appealed to the marketing group to realize how far they were missing the point, but they wouldn’t adjust their campaign.”

After weeks of pointed emails and arguments, Rhett did manage to get the box-art massaged upwards to suit a slightly older audience. Despite this, the marketing team kept its sights steady. The audience was 8 to 12 year olds, full stop.

In the end, none of this mattered much. The final advertising push in the month before release was minuscule to the point of non-existence. If Infogrames wanted tweens to buy this game, they weren’t pushing very hard to snare them either. With no buzz there would be no press coverage. And with no press coverage there would be no sales. Everyone was ignoring Moonbase Commander because no one had been given a reason to pay attention.

***

Rhett woke from a fitful sleep on Tuesday, August 13th 2001. He hopped out of bed and jumped on-line and clicked through to gamespot.com—his go-to for early game reviews. It didn’t take long to find the Moonbase write-up and when he did he skipped straight to the score. His body twitched, struck by a hot bolt of pride when he saw the 8.3 out of 10. A damn fine score. Concrete validation that his long journey was over and—according to someone else besides him—well worth the trip.

Rhett savored the number before shifting his eyes to the review proper. The opening paragraph cooled him down considerably.

“MoonBase Commander is a budget-priced game whose almost nonexistent advertising positions it somewhere between a cute product for young kids and a strategy game for dummies. It's hard to imagine a marketing campaign more likely to ensure that Moonbase Commander is ignored by virtually everyone. That's a shame, because it's one of the most accessible and uniquely addictive strategy games this year….”

Here was a clarion death knell for his beloved Moonbase, ringing in the form of a great review. These three sentences perfectly summarized Rhett’s persistent fear and frustration with Infograme’s handling of his pet-project. It might have given him some measure of comfort to know that their chronic disinterest in this new property was plain and public knowledge, and that at least one journalist was doing his best to raise its profile. But by stating the painfully obvious, Gamespot had made it clear that most of the damage had already been done.

More reviews trickled in over the course of the day and the following week, many enthusiastic, a few of them middling. Whether positive or negative, Rhett found himself in agreement with most of their general points, always willing to concede where Moonbase Commander was weakest, yet grateful for the attention and ever hopeful that the critical consensus would carry the game forward. Word-of-mouth was his best hope now.

As summer pushed into autumn and then into winter, Rhett scoured the internet for signs that his sapling had taken root. There was some positive evidence that people were flocking to this funny little game with the silly name and stupid box art. Various multiplayer networking apps and fan sites—like the now defunct Moonbase Command Center—popped up and stuck around for a few years, breathing new life into the game.

But by the year's end, in spite of its brief critical high-point, word from the top confirmed the worst. Moonbase Commander was an utter financial failure. A later intellectual property assessment would quantify this failure with an actual number, pinning the game’s value in a range between $0 and $100,000—a pitiful chunk of change far less than was ever poured into its development. This hard reality put an immediate end to all conversations about the future of the property, if there had been any talk at all.

When awards season hit in the final weeks of 2002, Moonbase Commander showed up on a few lists in peak positions. The now defunct All-Out-Games nominated it for their Game Of The Year, while Gamespot and IGN both dubbed it the “Best Game No One Played”, one generous pat on the back before it disappeared from the mainstream forever.

This unequivocal praise didn’t do much to lift Rhett’s spirits. Sure, dark horse awards gave Moonbase Commander fans a tepid form of indie cred, but they could not lift the spirits of the men and women who had worked hard to bring the game to life—devs who’s work most gamers would never get a chance to see and experience for themselves.

***

Video games are a curious multi-medium, perhaps the strangest coagulation of technology, vision, and talent that has ever bubbled up on this earth. They are vibrant and dynamic ecosystems of logic, art, sound, music, and meaning that have the power to surprise us at every turn with their particular whims and peculiar foci—today you are a space marine saving the galaxy, tomorrow you work for passport control at the border of a nameless Balkan state, next week you’ll try your hand as the coach of an American football team. And if you’re really lucky, one day you’ll be a moon-base commander exploring and conquering some faraway lunar body.

For over four decades, video games have harnessed the sum total of every artistic medium known to human society for their own eclectic purposes, building on centuries of expertise and imagination and transferring them to the digital realm, remixed and mangled for our pleasure. But with their technological breadth comes an inadvertent expiration date. Contingent on the technology that spawns it, the lifespan of any given video game is woefully short compared to other media forms. And any title that does not find its audience fast is unlikely to persist. There are few second lives in our industry, and even those games lucky enough to live out a first are often forgotten after one or two generations.

The story of Moonbase Commander—its genesis, growth, and swift decline—is not unique in this industry, not by a long shot. Countless other games made over the past few decades have suffered a similar fate—feisty titles that came and went, making only the slightest whimper in their passing.

But they are no less interesting for their transience and no less deserving of our attention. But how do we speak properly of these lost and forgotten gems? And how do we honor that which we cannot experience first-hand in the years and decades to come?

Perhaps we have reached an age where tenacious physical effort is the last truly impressive measure of value. In a decade where the tools of art production have been democratized to such an extent that everyone can be a writer, photographer, musician, or filmmaker with the right app and a few spare minutes, perhaps the only art capable of impressing us now is the work that takes months or years or decades to gestate and accrete. Money can buy almost everything nowadays—beauty, credibility, celebrity, power—but Time has never been for sale.

As Rhett surveys the three arduous years he spent conceiving, designing, and building Moonbase Commander with his small but devoted team, he finds no overarching lesson or moral in the effort. He sees only a handful of tiny facts that shine clearest.

He’s proud of his persistence, for one—of the “sweat equity” he poured into his game. It’s common wisdom that beginning is half the battle. But when there’s no end in sight, it can make a person wonder if the starting gun has actually been fired. For that, a person’s dogged pursuit of the goal is all the more impressive.

Rhett is also incredibly grateful for the passion and integrity of the people who carried him to the finish line—colleagues who shared his enthusiasm and kept him on track. Fostering this common passion, he points out, is one of the most essential ingredients in a game’s development process, and Rhett attributes the critical success of Moonbase Commander to his team’s perfect chemistry and love for the project.

As for its marketplace failure, Rhett has his own strong opinions: failure in some quarters to understand the proper audience and appeal of the game; lack of devotion to a uniquely odd IP; institutional allergies to anything unfamiliar and off-brand. Maybe he's right, maybe he's missing some critical piece of the story. But whatever reasons lay behind its poor sales, the simple fact is Moonbase Commander never found a broad audience and that killed its immediate future prospects then and there.

But Rhett prefers to highlight the positives of those days. Humongous, he remembers, was a bastion of incredible talent and untapped creativity, although he doesn’t regret a moment he spent there, even in the later darker years when he had every reason to believe the worst about the company’s direction. And there were plenty of reasons to worry.

In the span of its first eight years, between 1992 and 2000, Humongous had developed and released over forty games. In the subsequent nine years under Infogrames’ guidance, its output fell to just half that, with the majority of new titles being limp updates of their popular Backyard Sports titles. What had once been an engine of new ideas was now a factory peddling pre-fabs. “We could have been racehorses,” Rhett says of this downturn. “But they had us pulling ploughs.”

Rhett left Humongous Entertainment in the summer of 2003, severing all ties to the game he had labored to make for a full third of his time there. And now, twelve years later, he’s wistful about those faraway days:

“Just because you think a game is great, it doesn't mean that everyone else will. Let's face it, Moonbase Commander is sort of an abstract little game. Its concepts are mathematical, logical, mechanical. Its not big on characters or story, and is at its best when 4 friends can go head-to-head. Heck, it's turn-based as well. These design choices aren't going to result in the broadest appeal.”

At the end of the day, maybe Moonbase Commander's lack of traction can be distilled down to this: its profound oddness—the same quality that makes it so unique and so intriguing even now, almost fifteen years after its release. Contrary to Infogrames' damning fiscal report, it may be that reports of the untimely death of Moonbase Commander—this present article included—have been greatly exagerated.

In the last two years, Moonbase Commander has been resurrected with a second life, in spite of everything, with a small but devoted group of admirers. In 2012, Good Old Games released a perfect port of the title, unretouched and joyous as ever. And now the game has appeared on Steam as well, with full on-line multiplayer support for the first time.

For Rhett, this is a modest win. Although he hasn't had any creative or financial stake in Moonbase Commander since leaving Humongous in 2003, he's thrilled to see his pet project roaming around in the wild and finding a new audience. But his proudest accomplishment came thirteen years ago when he stamped the gold master and archived the project. “Who were you designing it for?" he had asked himself each and every day during its development. The answer was always the same: "I was designing it for myself.” And he was the only to whom he had anything to prove.

Moonbase Commander isn't Rhett's baby anymore, but the original idea and all those years of effort still belong wholly to him. His memories of those initial days are as clear and present as ever and he gets a bit giddy talking about the whole process. What had started out as a series of kitchen table sketches fast became a fully functional game. And soon that game became an obsession he vowed to finish at any cost.

So that's exactly what he did. Beyond that, it's mostly noise and nonsense.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like