Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

When an iPhone project begins in 2008 and launches in 2010, that's a huge challenge -- and 100 Rogues developer Keith Burgun here describes the bumps in the road that the well-liked, high-quality game has hit on its long slow journey towards release and profitability.

[When an iPhone project begins in 2008 and launches in 2010, that's a huge challenge -- and 100 Rogues developer Keith Burgun here describes the bumps in the road that the well-liked, high-quality game has hit on its long slow journey towards release and profitability.]

In December of 2008, my team and I began working on our iPhone game, 100 Rogues, which wouldn't get released until May of 2010. A widely reported iPhone gold rush combined with our desire to get a great game out to as many people as possible seemed like a great match, and so we charged into development full-force.

Strangely enough, the concept for our game, initially, was to "make a POWDER clone". For those who don't know, POWDER is a roguelike game that's been widely ported to a ton of platforms. For those who don't know what a roguelike game is, it's a genre of computer game that's been very active for 30 years (they're named "roguelikes" after the game that started it all back in 1980, titled Rogue.)

Imagine turn-based Diablo on Hardcore mode with high scores -- randomly-generated maps, turn based combat, and crushing difficulty usually are hallmarks of the genre.

Due to the fact that we chose our price point first, we ended up expanding out in a lot of ways that took us completely off the POWDER track. Probably the most striking difference is in presentation -- our game is pure fully-animated pixel art, with an original score, opening and closing cutscenes, and a detailed user interface.

Though we had originally planned for it to be un-animated and rough, like POWDER and many PC roguelikes, we eventually decided that the should look and feel like a Super Nintendo or PlayStation release.

Gameplay-wise, 100 Rogues has a skill tree (similar to Diablo II's) and is highly tactical -- most of the spells are not too helpful unless applied at just the right moment. I was also heavily inspired by the boiled-down simplicity of Mystery Dungeon: Shiren the Wanderer and even games like Team Fortress 2, and I tried to make the items system be as simple as possible.

So, no two items do the same thing; each item has its own specific role and doesn't step on any others. This again stands in stark contrast, I think, to the design of POWDER, which is much more of a conventional roguelike game. Again, most these changes were largely sparked by the price-point -- which is very relevant to my overall point here.

Unlike so many commercial games of today, 100 Rogues is not about completion; it's about improving your skills at the game. It follows more closely with an old arcade game like Galaga or a competitive game like Chess than it does Final Fantasy. A huge concern of ours was to make sure this element of the game was exorbitantly clear to our players.

Our approach to making this clear was to dispel the "hero" image of the player classes, and paint them as societal rejects -- losers who seem as destined to fail as they actually are. To our surprise, this seemed to have worked; the expected complaints about the game being "too hard" simply because people couldn't complete it never came.

Our approach to making this clear was to dispel the "hero" image of the player classes, and paint them as societal rejects -- losers who seem as destined to fail as they actually are. To our surprise, this seemed to have worked; the expected complaints about the game being "too hard" simply because people couldn't complete it never came.

The game was also very well received by all who formally reviewed it, getting at least four out of five stars from every publication we're aware of (to be fair, there were early complaints about the stability of the game, but this was addressed early on).

Though we started in 2008, we didn't really understand what the game would be until somewhere in late 2009 or early 2010. Furthermore, we lacked an overall gameplan for marketing the game, beyond simply being active on forums and word of mouth.

The experience of trying to guerrilla-market 100 Rogues was, and continues to be, frustrating. The story goes something like this. Sales are sucking. We work our asses off on a significant update and on promotional materials (be they a video, a contest, an illustration, or just a blog post).

The update goes live, sales increase ten-fold, and everything is great, until we notice that on Day 2 after the update, our sales have reduced by 50 percent or more. Same with the next day, and after two or three days, we're back to square one.

It feels like the only times we have good sales are when we are at the top of the "What's New" app store page, because of a patch. This speaks to the aforementioned top-heaviness of the App Store (by the way, it isn't possible to release patches any more frequently than our team does; Apple takes about two weeks to put one out, and we usually have another patch ready to go by the time they do). We only get any visibility when we're in the "What's New" section due to a patch.

Rumors about App Store top-heaviness and prices racing to the bottom began to surface, but I thought "Well, an exceptional game might be an exceptional case!" I've learned since then that for someone trying to get by the old-fashioned way, the App Store is every bit as rough a place as you've heard. What I'm pondering now is... Maybe that's not the App Store's fault. The world is changing in a way that is beyond anyone's control.

The way I see it now, the problem was simple: pricing. While our game was a break in tradition for most players and critics, when it comes to the game's development, team, marketing, and planning, 100 Rogues is very much a traditional affair. It was a bunch of guys getting together and making a game the old fashioned way: a design doc, a ton of pixel art, and waves of iterative gameplay testing over the course 18 months.

Very few iPhone games have taken anywhere near this amount of time, but for traditional computer games this was a pretty normal development schedule.

Since the dawn of the computer games industry, the model has been the same: spend all the time that you need (or all the time you can afford to spend) completing the game and making it shine, and then release it and hope that the sales roll in.

That's what we wanted to do. We wanted to be like our heroes, and we walked in their footsteps all the way to our completion. Unfortunately, as so have noticed, the world is changing dramatically, and this model may prove less and less feasible as time goes on.

With that in mind, some may be wondering how we're supporting a game with balance and content patches -- and how that affects sales post-release. We have released two massive patches to the game, as well as about two patches a month for smaller fixes and additions. One patch was the "Hell update" (Version 2.0), which added an entirely new world to the game, for free.

More than simply adding more levels to the game, a world in 100 Rogues is a really big deal. Worlds in 100 Rogues dictate monster type, tile set, music and even item drops, so making a new world basically means generating about 30 percent more content than we had at launch. This means tons of new Hell-themed monsters, several new songs, and a new animated Hell tile set, as well as several more monsters for other worlds and new items. Basically, it was almost like an "expansion pack", and we gave it away for free.

We expected a lot more of a response from this than we got. Part of the reason was that most of the Hell content was late-game, and so maybe not all of our players even got to it. Really, I had just hoped that this would show our fan base that we really, really care about the game and about our players, but I'm not sure that the message got through.

I guess it just wasn't clear to people how hard we worked on it -- or perhaps we worked too hard on stuff that people don't care about as much as we thought they did. Prioritizing and properly presenting your content is of utmost importance.

The second massive patch released our first in-app purchase -- a new playable class called the Skellyman Scoundrel. Now, classes in this game are huge in terms of gameplay; they totally dictate not just your strengths and weaknesses, but also the actions that you can take. They're also huge in terms of how much work they take to create.

Between all the custom character animations and balancing all of the abilities, as well as promotional shots and cutscene artwork, it really adds up. So we charged 99 cents for the Scoundrel, and dropped the price of the game down to $1.99. As with all of our promotions and patches, the sales spiked, only to settle back down to very low numbers after just a few days.

We also attempted several contests and other forms of guerilla marketing. I think at this point we've had about three contests, only one of which has actually gone anywhere. One was a "remix contest"; people could submit their remixes of our soundtrack and were offered lots of prizes.

That one went nowhere at all; only one person responded by sending me a totally original song that had nothing to do with our soundtrack. Then we had a Screenshot contest that offered no prize at all, which seemed to anger some people, who said "it sounds like you just want us to do your marketing for you".

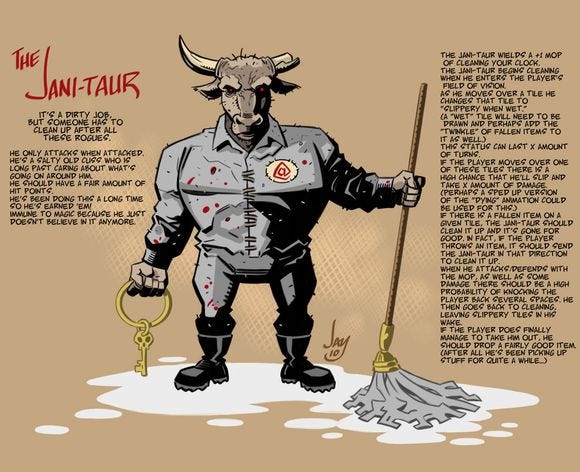

Finally, we had the "Design-A-Monster" contest, and I cannot tell you how much of a smashing success this was. We had dozens of submissions from all sorts of people, ranging from young children (one child submitted a monster idea called the Psychotic Robotic Wolf) to professional comic book artists (one of which won with his submission, the Jani-Taur, a Minotaur with a mop). It was a real blast and people seemed to have a lot of fun with it. Our prize for the winning submission was simply that we'd implement the monster into the game (which we still have to do for the Jani-Taur).

Now that our game has been out for six months, it has finally become clear to me that our plan was not economically viable. There were human errors involved and I'm not going to say we didn't make some mistakes with marketing and pricing, but there are a few lessons I learned that I'll be taking with me on my future projects.

1. If you do not have a big IP behind your game, give your game away for free. Out of the top 100 paid iPhone games right now, something like 70 of them have very fancy-pants licenses. This is extremely important to the average iPhone gamer, who really is just trying to avoid getting screwed. This is their motivation for gravitating towards stuff they've heard of; they feel that it is reliable.

Customers are more willing to experiment and try out your non-fancy-pants-IP game, but only if it's free. Players don't have to invest money to see if the game is well made and/or something that they'd enjoy.

Reasonable, fair in-app purchases (IAP) are a much better way for you to make money. This is all, of course, assuming your game is a relatively new idea; but if it isn't, then why are you making it?

2. Try not to spend more than $30K on your iPhone game. That is, assuming you care about making any profit on the game. 100 Rogues is by no means a "failure" of an iPhone game -- again, it was well-received by the critics, had good press on iPhone gaming sites, etc. We're six months in, and we still are very optimistic about our future, but we haven't come close to making ends meet.

Also keep in mind that "small scope" does not mean "bad." Some of you probably still have a Tetris-loaded original Game Boy next to your toilet. Tetris is 32 kilobytes of monochrome graphics and some kick-ass game design. Great game design doesn't cost tens of thousands of dollars; it just requires some understanding and care -- take advantage of that!

3. Prioritize additional content. You can probably sell one single item as an IAP if you market it properly. Giving extra content away for free is great and can send a really great message to your fans, but you have to make sure that what you're giving away will be something that people really appreciate and understand.

The days of, "Hey, you give me a bunch of money and I'll let you see if you'd like my game" are over, and that's a good thing. I've complained for years about how marketing has been the only thing that seems to matter for a games' success... a game could be horribly broken and boring, but if it has a standee at GameStop, it'll be a hit (I worked there for awhile and saw this happen first-hand many a-time).

If players can freely access all games, then word of mouth about the quality of the game will be far more effective in bringing the good stuff to the top. The App store is extremely top heavy, we all know this, but if developers all start to target the "Free Apps" section, I think that section would be a lot looser and a lot more well-rounded.

If players can freely access all games, then word of mouth about the quality of the game will be far more effective in bringing the good stuff to the top. The App store is extremely top heavy, we all know this, but if developers all start to target the "Free Apps" section, I think that section would be a lot looser and a lot more well-rounded.

How do you make money? In-app purchases. Zynga is worth more than EA and their game is FarmVille. (Is your game as good as Farmville? It had better be at least that good, or else why are you bothering making such a terrible, terrible game?)

Don't bother putting ads in your game. Players hate it, it makes no money (we tried it, believe me), and it ruins what little art direction you can afford to create and then fit on that little screen.

Give players a great, solid, complete game that they can play forever -- for free. Then dangle totally awesome stuff in their face that you know they're dying to use for a fair price. Players will actually want to give you money if they really like your game.

Hopefully the experiences I've shared here will be of use to other developers in trying to market their games. Remember: this change in the way the market works is good for all developers and all gamers. The only people it's not good for are the investors -- the people whose only role it is to put up tons of money up front in the hopes of getting some back.

As I'm sure you're aware, the relationship between these people and the actual content-producers in all artistic industries has been rough, to put it very kindly. However, things are changing for the better - we just have to stay in touch with how they're changing if we want to succeed. It's an exciting time to be a game developer!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like