Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

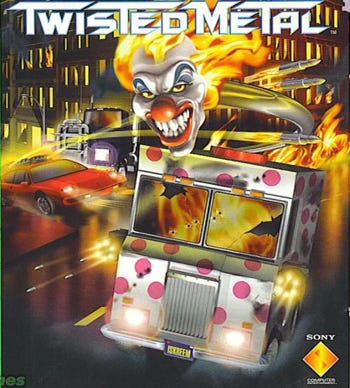

Eat Sleep Play's David Jaffe is renowned for his work on the God Of War and the Twisted Metal series, and Gamasutra catches up with him for an in-depth interview on the state of the industry, casual games, and the console war.

From the massive popularity of his God of War franchise to the formation of his new studio Eat, Sleep, Play, which has a multi-year, multi-title deal to develop PlayStation 3 titles for Sony, outspoken developer David Jaffe has become an opinionated and influential force in the industry.

Gamasutra recently had a chance to speak to him by phone about the unusual creation of the upcoming Twisted Metal: Head-On for the PS2, as well as his thoughts on the directions the market is taking right now, and how his new development studio Eat, Sleep, Play fits into the equation.

OK, so, the first thing I want to talk about is the new Twisted Metal game. It's really interesting to see a kind of "all encompassing" title. Especially, even though you've been involved in most of the projects since the series started, it's gone through so many different developers, and evolutions. How did you get all that material together, and make that game?

DJ: Well, with the exception of 3 and 4, I've been involved with every iteration of the series except Head-On.

And my business partner, Scott Campbell, and most of the guys that we took from Incognito to start Eat, Sleep, Play, they worked on all those games as well as Head-On. So with the exception of 3 and 4, we just had all that stuff sitting around on archives and things like that.

And everything else was brand new; the documentary that we made was brand new, and the levels that we did for Twisted Metal: Black were based on existing levels, but those had a lot of brand new work done to them as well. So most of it was honestly either new work, or stuff that was sitting around that we had had, that we had been hoping to find a good opportunity to use, and this was a great way to do it.

It's interesting because the PS2 is reaching... it's certainly not ending, but it's reaching a new phase in its lifespan. And I guess it's interesting to see what could've started as a simple PSP version, or port, has taken on a new life. How do you see the PS2 right now?

DJ: You know, I still love the PS2. I mean, every week I look at the numbers and see that it's still selling a pretty healthy amount. You know, obviously the new game releases have dwindled pretty significantly -- at least the ones that are significant and substantial -- but I love it.

You know, I had a debate with a bunch of people online a couple of days ago, where it's like, "Yeah, new technology is exciting, and new graphics are sexy and cool, but for me, I love the idea of an affordable gaming system with tons of software, and just that mass accessibility."

And so for me, I love the idea that we're putting out a really consumer-friendly priced product, lots of stuff on it, a lot of people can give it a try -- people who have either never played Twisted Metal because they were too young to have played it, and they're getting maybe a hand-me-down PlayStation 2 from their brother or sister, or the hardcore fans.

To me there's something -- I don't know -- I like very much the idea that we're still entertaining people who may not have made the leap to next-gen yet.

Because as exciting as the next-gen is, that's not everybody. You know, there's a lot of people that, either by choice or by necessity of cost, have not been able to make that leap yet. The fact that we're still able to put good stuff out for them is gratifying. I really like that.

Do you think that publishers are abandoning the PS2 generation too early?

DJ: Well, I think it's a chicken/egg thing. Look, I think if I was a publisher, I definitely would at least be putting some of my ammunition in the PS2. I definitely don't think I would be like, "Oh, let's spend fifteen million, or even ten million dollars on a brand new IP for the PlayStation 2," but, you know, I think that there are lot -- you know, worldwide, over a hundred million people who have that console.

And so I think there's definitely more gas in the tank, in terms of being able to make money off of it. And we'll see. We'll see how this game does; we'll see how some of the other titles coming out from Sony do. You know, there's a Ratchet game coming out, based on the PSP game, so we'll see how it does. But yeah, I'd love to see the PlayStation 2 continue, at least for a couple of years, with new releases.

What's also interesting about this project, to me, is that up until very recently, it's been hard for people to get their hands on games from prior generations, or earlier works of developers they might have discovered later on. The Wii's Virtual Console is one way to do that now, but this is a different sort of approach. What do you think about the importance of that? Does that drive it, or was it just like, "Hey, we have all this cool stuff, let's chuck it in!"?

DJ: Well, "chuck" wasn't the verb that we chose. (laughs) But I mean, it wasn't so slapdash. It was definitely that we made conscious choices about what we wanted to include, and we wanted to create a product that could sell like a substantial piece of gratitude for fans of the series. And so, we didn't just throw in stuff that we had sitting around; there was conscious thought that went into it.

But in terms of, you mean, how do I feel about other people being able to play work from earlier systems, and see it now? I think that's cool! That's great. As long as it's compelling; as long as it can still hold up. I'm like a lot of people, I buy a lot of these retro packages.

It's funny, I just reinstalled GameTap on my home PC today, and I was playing a game when you called. It's kinda like, I love going back to those old games, and I love that they're available, but I'm not one of these guys that's like... you know, I do think games have -- it's not like movies, unfortunately, where you can watch Casablanca and get caught up in it.

Kinda hard to go back and play Battlezone, and appreciate it for anything other than the nostalgia factor, as well as the appreciation factor of what it brought to the table in terms of the evolution of gaming. But in terms of being able to get engaged in a game from 5, 10, 20 years ago... I don't know about you, but for me, I find that hard to do.

It can be. What do you think about, you know -- this isn't totally analogous, but for example, Square Enix will take a game and they'll remake it from scratch. And you find that with other developers, too, and your project is sort of like that. Do you think that's a good way to keep the old, classic titles alive, rather than just shoving them out on compilation discs or software services?

DJ: Well, the Square thing is, though, what they -- I have the Final Fantasy remake on my DS... Or, Final Fantasy, what was it...

Three.

DJ: They didn't actually change much of the game, though. It was just a graphical upgrade, yeah?

It varies from title to title, but do you think it's the graphics or the gameplay? You know, that's another question, I guess. What that has to be revamped?

It varies from title to title, but do you think it's the graphics or the gameplay? You know, that's another question, I guess. What that has to be revamped?

DJ: Well, I think it's both. I think that there's an expectation from consumers; it doesn't have to be the latest and greatest graphics, but they have to be competitive enough that they will immerse players in the world, based on what they're visually used to. But then I think the gameplay as well, you know.

I have not gone back and replayed, what is the game that they put out recently... It may be one of the Final Fantasies, I don't know, but it's like, you know, there's part of me that recently has been wanting to play, what was it, Orcs & Elves, from id, from Carmack?

And I saw a review that was actually slamming it for this, they gave it a pretty low score, and were like, "This is fine if all you want is old school dungeon crawl with turn-based combat." And part of me was like, "Ooh! That sounds great!" I'd love to play Wizardry again; like really old school Wizardry. So there's part of me that really likes that they're doing that.

But there's also part of me that thinks, after twenty minutes, that it's just not engaging enough to stay involved with. So, I don't know. If somebody said, "Remake Twisted Metal," or, "Remake God of War," you could go to the nugget of what those games are, and hopefully if you're a fan of those games, what makes those games good. But I think that you have to do a lot more than just a graphical upgrade for me to be satisfied and involved with a project like that.

Because I think that, for better or for worse, expectations of gamers -- and I don't mean in terms of production values, or explosions, or graphics, but just in terms of the meaning of the interactive experience. You know, for people who those titles would actually make a difference to, who understand the name Twisted Metal, or Final Fantasy. Not necessarily the casual games market.

But for those people, they need more, in their sort of "interactive meal", and I think I would want to definitely make sure that the game has changed, and evolved in some fundamental way before I went back and put a new coat of paint on something.

And speaking of casual games experiences, and the market, it's obvious that there's a lot of discussion about that right now, and I think people are finding it hard to define -- they're over-defining it, maybe? Making it more of a dichotomy, like, "Casual gamers are grandmas. Hardcore gamers are 18 year old guys." One end of the spectrum to the other. What do you think about that?

DJ: "What do you think about that, I just said to you, there?" I don't know if you ever watch Jiminy Glick but you just sounded just like him. But, what do I think about that? Well, I think on one end you're absolutely right about the 18 year old guy thing. Every game that we do now, one of the guys calls it the "Joe College Factor."

You know, you always think about, when you're spending the kind of money that we have to spend now to make console titles, and this is a mistake that we made on our Calling All Cars game. It's like, you know, "Is this guy" -- it's usually a guy, for better or for worse, it's usually a guy -- "going to feel comfortable and cool going into a game store at all, and saying 'I want to have that experience'?"

And that bar has changed dramatically. If you look at PS1 era games -- and I always called it back then "the 80/20 rule" -- that could survive. Which was: 80% of your title had to be grounded in some sort of thematic reality, and 20% of it could be fantastic.

And so, back in '95, '96, '97, a game like, for example -- with the guy with the mental powers, but he was also a soldier -- Psi-Ops. A game like that would've been a huge hit back in the day.

But as graphics get better, it's almost like the 80/20 rule on PS1 was 90/10 on PS2, and now it's almost 100%. It's like there's not a lot of room in the hardcore gamer's diet these days for -- not hardcore, sorry, that's wrong, hardcore has plenty of room for it. But in terms of the mainstream market of console games, it seems like there's not a lot of room for imagination on the part of the thematic. It's almost like it feels silly to them.

So we look at all of our games, and go, "How do we make sure that we are able to appeal to that very huge part of the market?" And the easiest way is to make a great sports game, or make a great military game, but those are really hard nuts to crack. So yeah, I definitely agree with the assumption that the console gaming market is really driven by that mentality. It's certainly how we decide what we're going to put into production on the console side.

Now on the PC casual side, we at Eat, Sleep, Play are absolutely looking to get into that market, and you'll be hearing more about that from us hopefully relatively soon, but we're not looking at it like 85 year old grandmas. You know, we're definitely -- I play casual games, and I play hardcore games.

We're looking at it, though, more from the sense that the thematics can be a lot more interesting, there are a lot more chances that you can take thematically. The game's meat has to be right there immediately -- it has to be fun within the first couple of seconds or else people are going to move on.

David Jaffe's PSN downloadable title, Calling All Cars

The other interesting thing is that people these days are used to doing this $19.99, download, try before you buy model. And people still do that, but if you talk to people now, they want the games free, they want them on Flash, they don't want to download an executable. Those are the things that are really starting to define that market. More of an expectation of the kind of experience they want to have.

And those people, who are looking for those experiences, I just think that there are more people who are willing to take on those experiences, and they go outside of the realm of the core gamer. So you will get the soccer moms, you will get the hardcore gamers, you will get the little kids trying those titles. Because the barriers of entry: A) It's free. B) You run it on your computer. You can get to the fun right away. So I think it makes sense that the casual games market is actually starting to grow in a significant way.

Well what do you think about monetizing it, if it's a free Flash game?

DJ: Well that's happening. I think there are about four or five business models for casual games right now -- at least that I'm aware of. And I was actually doing some research today [on a model] where even though your game is free, the developer shares in revenue with the ad company every time their game is played. And I definitely think those are going to have to be made to be financially lucrative, or people aren't going to keep making them.

But, what I have not noticed -- which I am very thankful for, and very excited about -- is that gamers seem OK with the advertising model. It's like, they're not going to pay, they're not going to go through the trouble of going wherever their wallet is and putting their credit card in, downloading a file; they don't want to deal with all that, and they shouldn't have to.

But they seem to be not only OK, but supportive of the fact that in between every few levels, you may have to watch a 10 second ad. Or on the side of the screen, there are going to be ads, and stuff like that. They seem OK with that. And that's really exciting.

I think the real question now is: Can significant advertising revenue be brought into that space, and how is a developer of games going to benefit and share in the revenue? But I think that's stuff that people who know much more about that market than me have been discussing for a while.

I am really excited to get to GDC this year, to attend some of those sessions, because I think, to me, that really is where a big portion of the future of gaming is. Not even so much the fact that casual, in terms of the game mechanics -- although that's part of it -- but just the accessibility of games coming through, free games, and web-based browser games, that is crazy exciting stuff.

I can't speak obviously to everyone you have at your new company, but you know, your background has been in these core gamer titles, like Twisted Metal and God of War. Do you think the people that you have have the skill sets to make both kinds of games, since you're interested in both kinds of projects? Or is it difficult to find people?

DJ: Well, I think the way our company works is -- you know, just like any other company that is successful, or somewhat successful, you get the lion's share of the spotlight. I think everybody knows that the games that we make are team based, so everybody's always contributing to our titles.

I think the reality is that we're all getting older; I'm one of the youngest guys at the company at 36. And part of that is fantastic in the sense that, our guys have discipline -- they come in, they don't fuck around on the internet all day long -- they get their work done. And that speaks to their, not their age, but that speaks to to their work ethic that I think they've gained by building a lifetime of work, and success from working.

So I think as we are getting older, we're finding that things like Ratchet, and Uncharted, and Mass Effect, and things like that, we're all finding that we still like games but we don't have the time to play those big epic games. So we're really excited to try our hand at some of these games that, now as we're getting older, we actually play now. And, I don't know, who knows if you have the skill set until you try it?

Do we think we're going to be the next PopCap? I couldn't tell you. We'd like to think that on our PC side we will, [as well as in] our relationship with Sony -- which is our core focus right now, our only focus right now. We hope that we're going to do awesome work there as well. But I don't know if we have the skill set. I think we're pretty good at play mechanics, and iterating, and we're pretty good at killing things when they're not fun -- and hopefully that will see us through, and get us into that market in a way that we're successful.

It's interesting. And I think that it probably is exciting to think about what you can do, because -- what I was talking about earlier, is that I think people aren't sure what the dividing line is, or where to go. As you said, there are several different models for getting a game into the hands of players, and there are different thematic opportunities. It's rapidly evolving right now.

DJ: It absolutely is. No one really knows, and there's a gajillion different business models out there that people are trying, and games are getting so expensive on the console, so it's a really exciting time, and a really scary time. And hell, every week I'll read Gamasutra, and there's a new story about a new casual games business model, or a new company that broke off and made casual games, or big games, or whatever, and there's a lot of activity happening right now. And that's part of the fun of it, I think.

And what do you think of the place of, like, you know, like the PlayStation 3 in this market, or, you know, how do you think that that market's evolving? Do you, I mean, obviously, you know, you still have a great relationship with Sony, and you're talking about that being your main focus, so it seems clear to me that you believe in it.

DJ: You mean consoles in general, or the PlayStation 3?

Well, you know, I guess... both. Either.

DJ: Huh. Well I love the PlayStation 3. I mean, I have a Wii, I barely play it -- not because I don't like it or appreciate it, I just, you know, it's not my cup of tea at the moment. Mario Galaxy, I thought was pretty cool. I've got to be honest: I didn't think that it was as good as Ratchet. I didn't get the huge big deal over it; I thought it was a really good Mario game, but I wasn't like, "Oh my God, it's Mario 64!" I'm totally in the minority in that.

Of course, I like my Wii; I love my 360, I think the 360's awesome; I really do love the PlayStation 3, though, and I was really excited to hear some journalists talking recently about the new Burnout. With Burnout, if you really want to play Burnout the way it's supposed to be played, play it on the PlayStation 3.

And I think now we're just starting to see the idea that the PS3 is going to be capable of ultimately being the best system out there, in terms of delivering the best games and the best performance. And, you know, I love the fact that Blu-ray seems to be doing really well, and seems to be winning the format war. So I'm a big fan of the PlayStation 3.

Of course I wish it was a little less costly, I wish it had a bigger market share, but I think all that is just to come. I don't look at the situation and think that it's: "Where it is now is where it's going to be." I ultimately see it being pretty close to ahead, if not totally ahead, in terms of Xbox, in terms of market share when all the dust settles. I'm a big fan.

What do you think about the future of, you know, people being able to create high profile, high budget, $60 console games, and find success? Budgets are rising on games. That's obvious. You have to sell more copies of a game to be profitable. Does that worry you about package software, $60 packaged software for next generation consoles? Do you think we're going to reach a saturation point, where that might be a problem?

DJ: Just the cost of making games, you mean?

Yeah, I guess so. The cost of making games, basically.

DJ: You know, I don't know. I think it's definitely nerve wracking. I think we're starting to see less games. I think we're starting to -- well, here's the part that scares me the most. The part that scares me the most is that I look at these break-even spreadsheets, when we're working with Sony on our games. You know -- this is how many units you have to sell to break even, and this is what your current budget is.

Let's put it this way: it's really, you're at a whole new level, and it's not scary in the sense that I want to get out of it, and walk away from the problem, but it really is amazing to look back at, say, Twisted Metal 1, and go, "OK, we were selling that for 49 bucks, and that cost about $800,000 to make." And we sold 1,000,000 copies, and we were just like, "Hell, this is great!" And now you look at selling a million copies of a title that's going to cost 10, 15, 20 million [to develop], and you're like, "Man, I hope the low end is a million copies!" Because if it ain't, you're screwed!

It's really scary. Especially when you're publishing on a single platform, versus spreading your title out amongst all kinds of places. So, you know, it's definitely on our minds, we definitely worry about it. But we don't necessarily know how it's all going to pan out. I don't know if it's going to mean less games, or -- the knee-jerk is to say that it'll mean less artistic choices, but I think if you look at the amazing games that came out toward the end of 2007, that does not seem to be happening.

It's really scary. Especially when you're publishing on a single platform, versus spreading your title out amongst all kinds of places. So, you know, it's definitely on our minds, we definitely worry about it. But we don't necessarily know how it's all going to pan out. I don't know if it's going to mean less games, or -- the knee-jerk is to say that it'll mean less artistic choices, but I think if you look at the amazing games that came out toward the end of 2007, that does not seem to be happening.

We are getting some amazing titles out there -- thematically, and technically, and gameplay wise -- like Call of Duty, and Orange Box, and BioShock, and Rock Band. So, you know, you'd think that would be a problem, but it doesn't seem to be.

Do you think it helps drive the ball into Nintendo's court, to an extent? Because the DS and the Wii have much lower barrier of entry to some of the smaller, and even not-so-small developers that can't afford the budgets, or afford the marketing dollars?

DJ: You know, maybe. It's hard to say. I don't have enough data -- which is not that it's not out there, I just haven't looked at it in a while -- about selling on the Wii. I mean, you know the first party stuff is selling really well. I saw recently that Carnival Games, which is a third party title, was doing pretty well. And so it's the same way when you asked me what I thought about PS2. I love the fact that there is an option out there for developers and gamers who are like, "Look, you know, we don't care about the bleeding edge so much. We just want to have a good time." So I think it's nice that that has opened up.

And I was going to use the word "niche," but I think considering the success of the Wii -- at least so far -- that would be a disrespectful word to use when describing it, considering how stunningly successful it's been. So what it may really be saying is that the vast majority who want to play video games could really care less if they're playing the leading-edge graphics. They just want to have a good time and get on with their lives. So, you may be right, that may be actually opening up a whole new world for developers. But I think it's too early to say if anybody other than the first party developers on Nintendo's platforms, like in the past, are going to be able to reap those rewards and benefits. Or if you're only talking about Zelda and Pokémon.

No, you're right. And I think that, just like we were talking about with casual versus hardcore, and PS2 transitioning into PS3, all of this stuff, I just feel like right now we are at a crossroads where we can't really see what's happening. All these things seem to be up in the air. Do you feel that way?

DJ: Yeah, absolutely. And then when you roll in the whole digital distribution model, in terms of what is going to happen to the brick and mortar stores, and is this stuff going to be downloaded through your television, or are you playing on your cell phone? There are so many options now, and that's the great news; the bad news is that nobody knows where this is going to end up. And so it's scary but exciting.

That's why, to me, I love the downloadable model. I saw something, it might have been on your site the other day, that the game industry estimates that they lose a billion dollars a year to used game sales. I love the digital download model for both casual games and free games. I love the fact that game makers are being able to play with, and experiment with a lot of these different ways to get games to consumers.

In some cases it's cutting out the middleman altogether, and going right to the consumer, right to the game player. So it's a real exciting time. I'm grateful to be in the business at this point in its life.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like