Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This article sheds a comprehensive light on today's market, leading to the last part of the series, which, in turn, touches upon opportunities and ideas on what to do and how to behave in such a challenging market.

June 28, 2024

In a previous article, I discussed what has happened in our industry in recent years. I outlined the fundamental problem facing game developers and publishers—the market is hugely overloaded with thousands of games, and players, statistically speaking, do not care about any new game. They won't even know about a game's very existence if it hasn't been heavily marketed. That's the grim reality.

In this "episode," I will discuss several factors shaping the gaming industry today and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future:

The situation of gamers, who are becoming increasingly less forgiving and putting high pressure on publishers. I present some fundamental results of the market research we did on gamers as Try Evidence.

The emerging trend of publishers and investors becoming more cautious.

The industry's consolidation issue emphasizes that the economy (hopefully!) will be a driving force shaping the industry.

This article sheds a comprehensive light on today's market, leading to the last part of the series, which, in turn, touches upon opportunities and ideas on what to do and how to behave in such a challenging market.

Like all consumers in an oversupplied environment, gamers are becoming increasingly choosy. Today, if you invest hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars to get them to pay attention to your game, it still has a chance of success only if it is truly sensational. That is if it manages to defend itself against the increasingly exorbitant so-called points of parity - elements and features that a product must meet for its purchase to be even considered by consumers. For example, in a classic FPS game, there must be great shooting; the aiming must be precise, and the player must have a sense of firepower, recoil, etc. In a classic RPG, interesting quests must be consistent with the storyline, universe and, increasingly, unique side quests.

Unfortunately, today, we increasingly see that the level below which competing for gamers' hearts is difficult, and profitability is questionable, is 80 out of 100 in review aggregators.

It's difficult for games rated between 70 and 80 points by the media to gain popularity, even if they are still considered good. And how many, even experienced developers today, can ensure a game landing with ratings above 80? Contrary to appearances, only a few. We frequently read about these teams, but it's important to note that they represent a small subset of the most commonly discussed groups. Meanwhile, players' expectations continue to rise, and the bar is getting higher and higher.

This means the need for another vast investment: in conceptualizing the game product, controlling its development, and its technical production. Every developer and publisher without a huge production budget today must make up for it with a competent team, wisely propose relevant innovations to players and positively surprise them, take care of the game's reception in the media from the beginning, build a community around it, etc. And, of course, count on the miracle of being noticed when the time of release comes, among thousands of other proposals for which the creators also followed these steps.

We must also remember that today's gamer is a man with less and less time for individual activities, among which, in turn, there are more and more attractive leisure options.

How does a game have to present itself so that, first, it stands out among thousands of other games, and second, it encourages the consumer of culture to devote many hours just to it, not to watching movies, reading books, playing sports or other escapist hobbies, not to mention devoting time to family or daily obligations? Games compete not just with other games but with all entertainment in the broadest sense.

by Michał Dębek / Try Evidence CC BY-ND

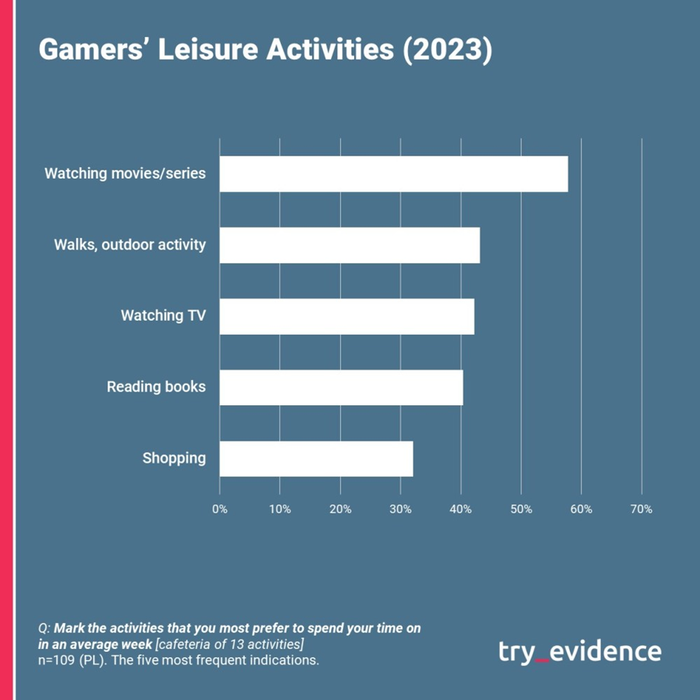

In the research we at Try Evidence conducted in 2023, we asked gamers about other hobbies they regularly and most willingly indulge in. In the Polish part, nearly 60% of players watched movies or TV series - that's obvious. On the other hand, more than 40% also watched TV or read books! More than 1/3 enjoyed spending time shopping or playing on mobile devices.

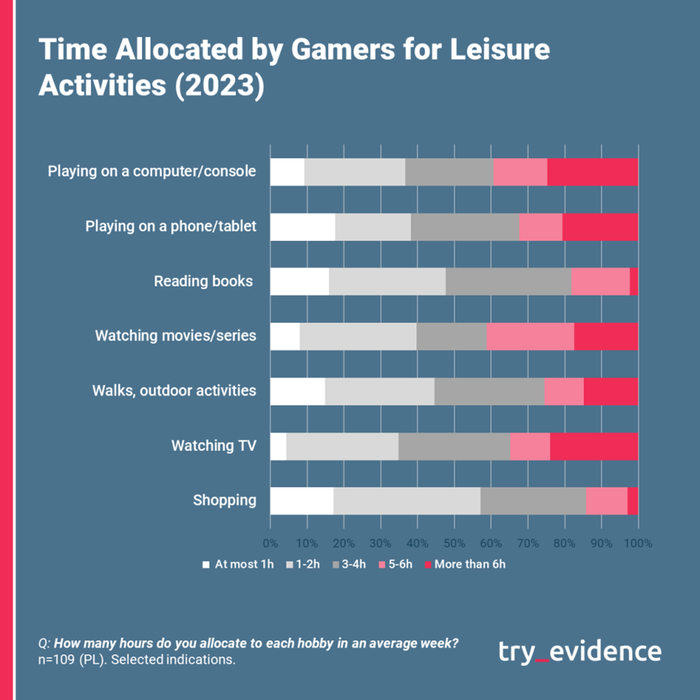

More interestingly, gamers who enjoy watching TV spend more time on TV in their average week than gaming, and playing on mobile consumes only a bit less time than playing on PCs/consoles.

by Michał Dębek / Try Evidence CC BY-ND

This means that a game you've been producing for several years is also competing for the player's attention and time with other exciting activities from the player's perspective. In short, spending time with your game has to be more attractive than watching TV or streaming services.

by Michał Dębek / Try Evidence CC BY-ND

This is another severe challenge, especially for small studios. It will also become increasingly difficult because huge studios choose to fight for small niches in original ideas and unorthodox storytelling (see, for example, EA Originals). One friendly journalist put it this way: "Truly independent developers in this situation are not only fighting against AAA titles but also against 'AAA indies' that are backed by giga-corporations." In turn, these big games will increasingly take the form of never-ending stories, with many spin-offs, DLCs, etc., further consuming players' precious time and money.

Experienced marketers of large publishers know that it is much easier to succeed with even moderately successful games under a strong brand than with excellent games under a brand that has yet to be built.

In the end, let's be honest – a player who sees an indie production often does not know they are looking at an indie game. A game is a game – it should be engaging, intriguing, operational on every device, and captivating. They expect AAA quality without realizing that the indie game being judged is not only separated by hundreds of additional positions of the world's best creators but also between, on average, 50-150 million dollars of production budget. Small developers and publishers have to come to terms with this.

By now, I'm sure almost all publishers and investors realize that financing underdeveloped games or investing in barely conceptualized games without strong brands and solid production facilities is fraught with huge risks. These risks steadily increase as the probability of success in such ventures dangerously moves towards zero.

In 2023, Steam's turnover was $9 billion, but only ten games (!) accounted for more than 60%. This is despite nearly 15,000 games debuting on the platform that year. Over 50% of those games never earned more than $4,000, and over 2/3 didn't even reach $10,000 in revenue over their lifetime.

In contrast, in 2021, game purchases provided Activision Blizzard alone with $5.1 billion in revenue.

To use the gold rush analogy: veins of gold do exist, but a select few reap them. Finding the next profitable venture requires courage, a budget, and much luck. Today, most investors and publishers tend to understand this and are more cautious in their investments than ever.

They carefully count every dollar, prefer proven intellectual property and create a climate of risk aversion.

To be considered seriously for funding nowadays, an indie studio should have a history, experience, a working prototype, a considerable wishlist, and an active community. All these factors are essential for the studio to establish its credibility.

This brings us back to the topic of marketing. In the current game development landscape, developers must thoroughly understand the market and at least have a reasonable marketing vision for their game. This is not only important for promoting the game in the target group but also for establishing credibility as a serious team in the eyes of publishers.

While there's still room for exciting projects, new intellectual properties, and various gaming experiments, they must be grounded in market reality and thoroughly tested before anyone decides to invest in them.

It is crucial to give a reasonable answer supported by data when asked, "Why do you think this game will be successful?"

Relying solely on historical sales data for similar games is no longer sufficient, as publishers now understand that past performance has limited predictive value. The gaming market is constantly changing, with several game launches changing the standards, which makes it difficult to estimate how gamers will behave in the future. To predict future gamer behavior, one needs to combine retrospective and historical data with prospective data derived from precise market research, usage and attitudes studies of gamers, and trend spotting.

I believe that the gaming industry is reforming and maturing as it undergoes a period of strict vetting for game ideas, production and publishing approaches, and financial assumptions, leading to a concentration in the long term. As one of my industry colleagues pointed out:

"This process is likely to lead to a consolidation of the industry, similar to how the film industry consolidated in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, with a few major players emerging from a plethora of producers".

These majors dominate the market and shape the industry's direction, much like Warner, Walt Disney, Universal, Columbia, and Paramount did in the film industry. This consolidation trend is happening again in the gaming industry, with the possibility of further expansion from giant Asian players like Tencent and NetEase. However, this may not necessarily have negative consequences for small studios. The larger entities are less agile, less willing to take risks, and less likely to enter small niches or change direction.

With the naked eye, you can see fewer fish from the bridge of a captain's tanker than through the window of a small fishing boat.

Small, well-organized, and well-structured marketing teams will still have a chance to coexist with industry giants.

In the film industry, independent cinemas do not directly compete with multiplexes that screen blockbusters. Instead, indie movies and cinemas tackle unusual topics and controversial issues, use risky means of expression, present a unique sensibility, and target relatively small audiences that may not be attractive to giant studios and the mainstream. Similarly, in the gaming industry, smaller developers can propose unconventional and niche ideas that cater to specific audiences. However, they must know what they are doing, who and why their target audience is.

In our industry, numerous unconventional projects have delved into significantly niche topics, some of which have even succeeded. However, plenty of small developers still pitch their indie ideas as a combination of two or three AAA games, each of which has sold millions of copies.

I think it will no longer be convincing to tell indie stories through the lens of AAA games and try to achieve grandiose productions with limited budgets and resources. This approach will naturally become outdated.

Mid-range publishers and mid-sized developers are also likely to become a thing of the past. "Medium games" from medium-sized teams are often middling (i.e., rated around 75 in aggregators) and are looking for their imagined medium players. However, there is no such thing as an average player, so there is no demand for average games from average developers.

Representatives from traditional industries may consider it to be a cliché, but in game development, it's a daunting reality: the cornerstones of any new project are the budget, financial predictions, and the profit and loss Excel spreadsheet. Indeed, these elements are equally, if not more, vital than the industry's highly acclaimed artistic vision, its relentless energy, and its profound ambition.

The studios that survive in this industry's "small post-apo" will need to place greater stress than ever, not only on the uniqueness and sensibility of their games but also on the sound economic judgment of their production intentions and commercial plans.

A friend from the industry summed it up nicely: "If you spend five years making a non-AAA game, there is hardly any chance that the project will pay off. Many studios go bankrupt because they cannot develop a game that takes, say, two years and achieves an 80+ rating on aggregators." Moreover, game prices are not increasing. Gamers are waiting for discounts, which they are already very used to. In our lab interviews with gamers, we frequently hear that even if they like a game, they will not purchase it at full price because it will surely be discounted by a dozen or tens of percent soon. Moreover, the $19.90 price point will likely become increasingly popular for new game releases.

In recent years, many indie game developers have focused on creating larger, production-inflated, higher-quality games. They have been trying harder and harder to turn toward A+, AA, or so-called triple-I games. However, such projects are only profitable with tremendous promotional support. This has probably finally become obvious to most of the industry. In the future, AI may help speed up game production, allowing developers to create games faster and at a lower cost. But this could also lead to an influx of low-quality games flooding the market, making it more difficult for players to find valuable games among the masses of shovelware. As players are already overwhelmed with generic game clones, the impact of AI on game development could make the problem even worse.

Our industry requires an army of professionals experienced in production organization, management economics, and data analytics. The time has come for game developers to create games not only based on creative ideas but also on financial data.

We are about to witness a paradoxical situation in which game developers must invest more money to create unique gaming experiences for players while using less money to prove the return on investment.

The studios that will survive must not only be ambitious and able to make a great game, or to build strong brands. They must also be financially responsible and well-organized and make decisions based on data gathered from international player surveys and continuous qualitative research, such as UX and mock reviews. As one of the producers friendly with me put it in a casual conversation: "From my perspective, the most difficult challenge in the coming years will not be to make a good game, but to make money from it; acquiring the right technologies or competencies is no longer as challenging as it once was. The quality of games is increasing, and many companies want to compete for the laurels of the best ones, but this drives up costs, which in turn raise the required break-even point for a project."

It's possible that simple yet effective ideas, such as "back to simpler games," executed with a few people, will make a comeback. This is because money is expensive in our industry today, as mentioned in our discussions with investors and executive producers.

*

In the last part of this series, I'll present:

Excerpts from the market research focused on gamers that we performed as Try Evidence.

Opportunities and Ideas: "What to Do" (in this VUCA environment and challenging situation).

You May Also Like