Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Developer, educator, and author Ian Bogost is back with his latest Persuasive Games column, in which he explores the phenomenon of Indie Game bundles -- what motivates their creators, their buyers, and what effect they may have.

From Humble Bundle to Steam Sales, from Indie Royale to Indie Gala, it seems like you can't go online anymore without seeing a new "game bundle" offering -- a set of unusual, overlooked, and independent game titles offered at a substantial discount for a limited time, often with a portion of proceeds donated to charities like the Red Cross or Child's Play.

It's tempting to let these bundles pass by without fanfare. After all, what harm can come from selling charming, clever, or unusual independent games and giving money to charity? But if downloadable games, free-to-play games, social network games, and other trends in distribution have taught us anything, it's that new distribution platforms often have a surprising impact on the perception and use of games.

So, what are game bundles, anyway? Here are a number of possible answers.

That game bundles are bundles is obvious, but what kind of bundles are they?

Remember those breakfast cereal "fun packs?" They come with many single-serving boxes of different varieties of sugary cereal like Apple Jacks and Froot Loops.

Sugary cereals are precious. Most parents won't buy them very often, and when they do they expect them to get eaten. And moreover, many parents aren't likely to buy sugary cereal at all; for them, the fun pack becomes a special treat, one meant to be repeated only occasionally.

While a casual scan of Twitter or Facebook posts might suggest that bundle purchases come from gamer "holdouts" too stingy to shell out even 5 dollars for a complete game, the sheer volume of bundle sales (sometimes in the hundreds of thousands of buyers), suggests that these bundles might be more like cereal fun packs than like discounted Corn Pops.

Game bundles resemble cereal bundles in almost every way. They collect eight or so titles together, offering a variety of hand-selected options. They gather them together in a convenient package, and they offer them at a substantial discount. While indie games are perhaps not so indulgent as sugary cereal, they are still a kind of extravagance for most people -- or at least a nonessential product, an exploration of a part of the video game shelves less commonly raided in large numbers.

Cereal fun packs also explain why deep discounts only work at scale. Internet utopians often celebrate "experiments" in digital distribution in which famous entertainers like Radiohead or Louis CK offer pay-what-you-want or low-price deals that produce enormous response, but they ignore the fact that those artists already have enormous followings created by years (or even decades) of traditional media -- just like fun pack buyers already know about Trix.

Selling more units of something requires selling to more people, and selling to more people means appealing to them in a way that overcomes perceived deficiencies in the product, among them simple indifference.

Selling more units of something requires selling to more people, and selling to more people means appealing to them in a way that overcomes perceived deficiencies in the product, among them simple indifference.

Bundles thus exert forces of both novelty and homogenization. Atypical customers try out unfamiliar goods, but in order to make them appealing those goods must be selected or adapted to make them less undesirable.

Current trends in free-to-play games are producing enormous player bases, but they do so at the cost of, well, cost -- only a small percentage of F2P players become customers, thus a very large user-base is required.

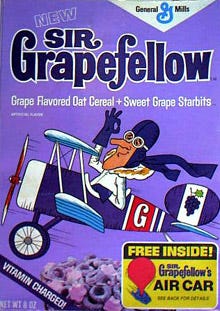

But a large market always entails a dilution of the product, making it more unassuming and homogeneous. So while bundles may introduce independent titles to a larger audience of gamers, the kind of titles most conducive to bundle purchases might turn out to be more like Apple Jacks than like, say, Sir Grapefellow.

Even a half-decade ago, the business of independent games was in a far worse state than it had been 20 years ago, when shareware games birthed titans like id and Epic. Even 30 years ago, disks in bags at local software stores may have offered greater financial opportunity than free downloads from obscure websites.

Then Xbox Live Arcade and PlayStation Network arrived, offering a highly controlled, low-volume, tightly (if sometimes weirdly) curated channel for games. Getting a game on these services spells almost certain success, but doing so is difficult.

Soon after, the Apple App Store, the Android Market, and Facebook emerged, offering enormous audiences accessible to everyone, but at the cost of very noisy storefronts. It's still possible to win the lottery on the App Store, of course, but it's more common to languish in oblivion. Steam sits somewhere between the two, both curated and noisy, where distribution is hardly a guarantee of financial victory.

Being a "working game maker" today is a lot like being a musician or an author: making stuff is easy, distributing it is relatively easy, but making meaningful money is nearly impossible.

Game bundles reduce the unit cost of games, and so it's impossible to deny that they are contributing to the "race to the bottom" in media pricing more generally. But because each bundle or sale only lasts a limited time, it exerts a different force, offering certain sell-through for one, but increasing potential reach thanks to the surrounding publicity.

In that respect, bundles are also promotional campaigns in which a temporary reduction in price with a particularly desirable placement results in free marketing with considerable reach -- while also delivering substantial revenue thanks to volume. Bundles are the retail end caps of the indie game supermarket.

Today's game marketplace is largely comprised of console games, mobile games, and social network games. Again and again, predictions of the death of PC gaming have circulated, but every time the PC rises up and reasserts its relevance. Bundles contribute to and extend that sentiment, first by making desirable, curated PC games available at a low cost -- but also by expanding the base of the PC movement to include Mac and Linux users.

Not all bundles impose the cross-platform requirement, but the success of the Humble Bundle, which only distributes games that work on all three OSes, has allowed supporters of underdog platforms to band together and make the case for themselves. The most recent Humble Indie Bundle sold almost 75 percent of its wares in Windows editions, but Mac and Linux split the remaining 25 percent almost evenly. Moreover, those buyers paid considerably more, with Mac users handing over 40 percent and Linux users 92 percent more than Windows users.

In addition to the cross-platform position, bundles also tend to prefer DRM-free titles. While some distribute Steam keys instead, that platform has itself established a reputation for kinder, gentler DRM compared the abusive policies of major publishers. In any case, all of the bundle providers talk about DRM in one way or another, showing that they recognize both platform availability and freedom as concerns for contemporary publishing.

This set of values corresponds with a techno-centric political position sometimes called cyber-libertarianism. Cyber-liberties advocates want to be able to choose technologies, products, and services without social, state, or economic coercion.

While cyber-libertarianism is usually associated with marketplace- rather than state-managed information networks, it also extends to the use of free and open-source software like Linux (which allows its users to customize or change a machine's operation), and anti-DRM positions (which are perceived to infringe on a buyer's right to do whatever they want with digital materials).

Humble Bundle in particular makes a point of highlighting the cross-platform and DRM-free features of its service as a primary value.

The fact that Linux users are paying more than Mac or PC users for the Humble Bundle provides some evidence that they are signaling an affinity with the products values, not just purchasing it for instrumental reasons. While there's no data to prove it, one can speculate that game bundles may also be converting some software pirates who crack products not to avoid paying, but because those products fail to provide them adequate "freedom."

We normally focus on the low end of the "pick your price" aspect of game bundles, but choosing what you pay also makes it possible to contribute far more than a game would normally cost. While the average purchase price for the Humble Indie Bundle #4 was $5.45, or a paltry 61¢ on average per game or charity, the highest price paid was $8,542, by Minecraft creator Markus Persson1. The tenth-highest contribution, at $650, came from the small software company 1up Industries.

When you go to a museum or concert hall or ballet studio -- any arts organization that relies on philanthropic contribution for its operation -- it's common to find a list of patrons who have given particularly generously. It's usually a dramatic architectural affair, names etched into stone or glass in an ostentatious way.

When the very wealthy make philanthropic contributions, they do so partly because they earnestly enjoy the arts. Some do so for influence too; patronage may offer special access to the board or directorship of an organization. But they also do it for reasons of social signaling and peacocking: "Look at me, I am a supporter of the arts."

When the very wealthy make philanthropic contributions, they do so partly because they earnestly enjoy the arts. Some do so for influence too; patronage may offer special access to the board or directorship of an organization. But they also do it for reasons of social signaling and peacocking: "Look at me, I am a supporter of the arts."

When the bundle websites publish the top ten contributors publicly, those names act as a patron's wall for indie gaming. The bundles sites also optionally link to a Twitter account, offering top contributors exposure to the tens or hundreds of thousands of individuals who pass through the virtual space of the bundle website. Patronage demands ostentation.

In the traditional arts patronage is very costly, with contributions of hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars required to secure the top spot on a benefactor's list. Notch's $8.5k would look paltry among donors to the average symphony.

But the low cost of entry to game patronage offers access to the everyman. At $720, the sixth-highest contribution to the Humble Indie Bundle #4 came from HobbyGameDev.com, which is run by indie game developer and Georgia Tech digital media graduate student Chris Deleon. This is hardly an affair of the 1 percent.

Patronage is emerging elsewhere online, most notably at the crowdfunding service Kickstarter, where many games seek funding. That site does not publish top contributions and therefore embraces the logic of the "anonymous donor," who not only enjoys the public reaction to his or her generosity, but also the private pride of having been "humble" in declining to accept the showiness of public display.

Whether it supports ballet or video games, patronage has no necessary relationship to the product sold. Patrons may or may not care about a particular exhibition, performance, or game when they make a large contribution; instead they are buying both general support and the vanity of being seen as a supporter. Downloading the games isn't even required.

---

1 In choosing this figure, I'm leaving out the HumbleBrony account, which aggregates payments from individuals in order to increase the charitable contribution rate. Together, that group paid $16,005.27 for Humble Indie Bundle #4.

The games contained in a bundle are generally meant for entertainment, of course. But the practice of participating in a bundle is also its own, separate form of entertainment.

For starters, bundles produce suspense. When will the next bundle arrive? What will it contain? You can sign up to be notified for the next bundle deal, thus ensuring a pleasant surprise sometime in the future, no matter what the bundle contains or whether you want it.

The Indie Royale bundle even offers a "blind" purchase, in which a buyer can get a special deal by buying in before the contents of the bundle are revealed. Running the risk of disappointment offers the pleasure of teasing chance and contingency, the same pleasure we get from game shows, reality television, and casino gambling.

Players often express glee or exasperation at the prospect of acquiring even more games from the Steam service thanks to a newly announced sale ("I still have so many I haven't played," one might read on Facebook or Twitter). In part, the public performance of this exasperation is itself a form of distraction.

But more perversely, players may have begun enjoying the collection the Steam keys themselves, rather than the games they unlock. Achievements and trophies offer collectables within games, but Steam seems to have catalyzed a desire for collection within the marketplace itself.

Then, when a new bundle finally does arrive, it becomes a spectator event. How many copies will be sold? What's the current minimum price? How much money will be made? Will Linux increase its share of payments by platform? Who will top the contributor list? The progress of bundles is often reported as news in the enthusiast and trade press, much like one might cover a sports tournament, including commentary from developers and projections about the possibility of besting a previous record.

Those who partake of the bundle spectacle need not buy anything whatsoever. They can check in on its progress, or even just talk about it. Many players take advantage of the opportunity to root for a favorite game or developer, or just to express an affinity with such a one on social media. This strange paramedia effect is created entirely by the bundle concept, quite separate from whatever experiences the included games might provide.

Finally, obvious though it may be, we must remember that game bundles and download channel sales are not mere goodwill. Bundle service providers are businesses seeking to create or maximize profit. Valve has been quite forthcoming about the fact that discounted games seem to yield greater financial benefit. And Indie Royale is run (with Australian download store Desura) by a division of United Business Media, the same multinational media conglomerate that owns this site as well as the Game Developers Conference -- they're definitely in it for the money.

But Humble Bundle presents an air of nonchalance that belies its status as Silicon Valley high tech startup. The service may have a deferential name, but it was backed by a $4.7 million investment from Sequoia Capital. That VC investment came after the company's tenure at Y Combinator, the Silicon Valley incubation darling.

Running a bundle site surely entails costs related to hosting and operations, but make no mistake: a multi-million investment from a major venture capital firm positions Humble Bundle as a distribution business interested in producing maximum leverage on digital downloads of games (and perhaps eventually other products, too). Business is business, but whether it qualifies as humility is an open question.

Another widely celebrated feature of Humble Bundle is its inclusion of a charitable contribution. Buyers can allocate a portion of their total purchase to charities like the American Red Cross, Child's Play, and Save the Children. While it's unfashionable to be cynical about charitable giving, there's a long history of corporations using charity as a ploy for sales. For example, to raise just $36 for breast cancer research from pink-topped Yoplait yogurt tubs, you'd need to eat three of them a day for four months.

Humble Bundle is clearly producing better figures than that, but it's hard to know how much better (they don't publicly disclose their charitable distributions). No matter the case, the point is this: while Humble Bundle and Indie Royale present themselves as unpretentious and hip and unassuming, they are deeply connected to the financial logic of the tech sector, even if their organizers do care about indie games. Nevertheless, these aren't grassroots volunteer organizations, and they aren't community festivals.

What does it matter how game bundles as game bundles exert forces on the industry and the marketplace? When we think about the effects of media, it's not enough to focus on the way the content of film, television, or games make us feel or the things they make us do. We also have to consider the effects of the media forms themselves.

Examples are everywhere, but to take just one recent example: Spry Fox announced a partnership with Disney's Playdom subsidiary, who will distribute their popular social network game Triple Town. The reason? That game's 150,000 monthly users proved insufficient to produce a meaningful profit, thanks to the low conversion rate of free-to-play games on Facebook. This effect is not a result of any properties of Triple Town itself, but of the Facebook platform and the way it has enhanced a particular kind of leveraged, user-driven business model.

Thanks to the sheen of low-cost, high quality indie games for every platform, bundle services have emerged to offer yet another new way to buy and sell games online. But in so doing, they have also blinded us somewhat to the effects they produce as a medium themselves. Bundles are not just transparent storefronts through which indie developers enjoy fame and success; they are also poised to alter the ecology in which games get created and used.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like