Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

When making a game you need to keep track of what resources you are burning. It's far more than just time and money. This is Midnight Hub's last post in a series about how to reduce stress when working with games!

This is part three in a series of blog posts about how to work smarter, not harder, on your game! I previously wrote about how to use the iterative ABC-recipe to make your game, and why you absolutely should not crunch when you make games. This time I’ll write about how we at Midnight Hub allocate time for tasks, how we work with sprints and why “time” and “money” are only two of (at least) six resources you need to balance when making your game. I’ll speak as a producer and project manager.

Lake Ridden is a story-driven firstperson mystery filled with puzzles, developed by former Minecraft and Paradox devs, in Sweden.

Lake Ridden is a story-driven firstperson mystery filled with puzzles, developed by former Minecraft and Paradox devs, in Sweden.

Before co-founding Midnight Hub I’ve worked at Paradox and Tarsier, among others. Comments and feedback on this piece are always welcome here, or you can find me on Twitter. Midnight Hub is a five-man army based in Sweden. Our upcoming game Lake Ridden is a puzzle game filled with story and mysteries. Let’s go!

When making something, anything really, you have to manage your resources. At their most basic form, your resources are: time, money and the scope of your product. Let’s cut them up and take a look at each category, so see which other sub-categories you should manage too!

Time, as a concept is kinda tricky for the human brain to understand. Some days seem to fly by while others crawl. When someone tells you got 40 hours this week to work on your game, what does that really tell you? Not much, probably. Especially when you have a job where some days you take one step forward and two steps back. Or when you start working on a totally new feature and no one is really sure how things should work or feel in the end. This is also the reason the Scrum method count points instead of hours. Time is hard to understand.

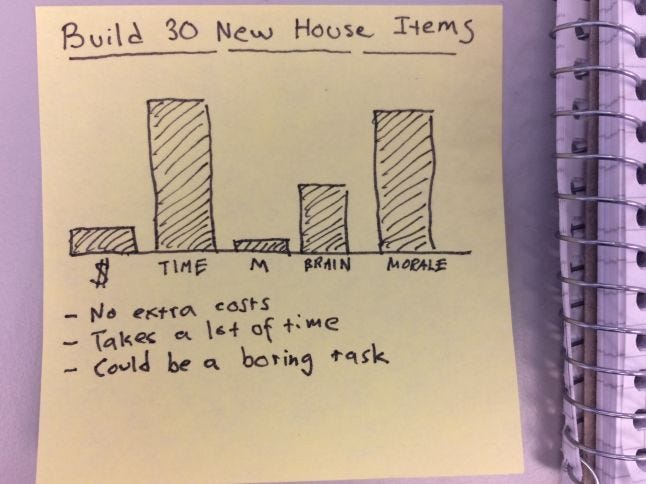

Not all tasks are born equal! Different tasks burn different resources from the team. A task like building 30 new props for an in-game house might not cost you any extra money, but it takes a lot of time for the artist making them, and if it’s monotonous work the morale of that team member can take a hit.

Not all tasks are born equal! Different tasks burn different resources from the team. A task like building 30 new props for an in-game house might not cost you any extra money, but it takes a lot of time for the artist making them, and if it’s monotonous work the morale of that team member can take a hit.

When making a game you (probably) have a finite amount of money before you have to release the game and (hopefully) earn back the money you spent plus even more to afford bringing more awesome games to this world! Some things burn through a lot of money, like salaries and paying a QA firm to do your bug testing.

Two other resources that you burn when working, may it be harvesting carrots or writing loot systems, is the physical toll it has on your body and the brain power it takes to perform. If you’re working heavy duty in a restaurant kitchen it may have a severe physical effect on your muscles, but perhaps not so much on your brain. If you’re solving complex, abstract problems all day in a spreadsheet you’ll most likely feel the effect it has on your brain at the end of the day.

I spoke about “materials” in the previous blog post. What are the materials you burn/wear out doing your work? When making games you usually need very little equipment, while other activities, such as refining paper from trees take a lot of equipment and materials.

The final (and perhaps the most important resource) you have to take care of is morale, or motivation. Dealing with a fairly easy task becomes very hard if you lack the motivation to do it. Loss of motivation can easily destroy a whole team. It’s very hard to buy motivation, most creative people are not motivated by money after a certain point. If you love money then making games is not really where you should be.

To recap, the resources you are burning to fulfill the scope of your game is: time, money, materials, brain, body and morale. The amount of money you have in the bank can be translated into the amount of time you have left to make the game. How many months of salaries and rents does that money buy you? And the amount of time you have left can be distributed to make different things for the game. Different tasks will burn different resources from your team members, may it be motivation or brain power.

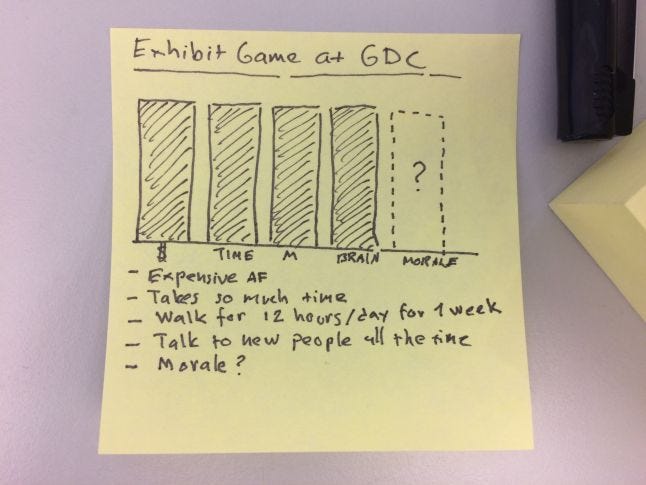

Some tasks burn a whole lot more than others. This is what we label a “Mammoth Task”. It’s something that’s expensive, takes a lot of time, makes your body ache and drains your brain. How it affects morale is hard to tell. If you showed your game to the press and they loved it, then perhaps you gain morale instead of burning it!

Some tasks burn a whole lot more than others. This is what we label a “Mammoth Task”. It’s something that’s expensive, takes a lot of time, makes your body ache and drains your brain. How it affects morale is hard to tell. If you showed your game to the press and they loved it, then perhaps you gain morale instead of burning it!

We have a term for tasks that require almost all of these resources to be burned at the same time: Mammoth Tasks. I quickly mentioned this in an earlier blog post. They are big, complex things that you may have never done before, that require a lot of brain power, that takes a bit of time and if you get them wrong the consequences may be severe. An example could be building a totally new light system for the whole game, or to get investors to invest in your company. If someone has a mammoth task it can make sense to let them work 80% or 50%, since these kind of tasks are extremely draining. Remember, the last thing you want is to crunch your developers!

Our project management philosophy is to always be as goal-focused as possible. Whenever it’s possible to measure or track anything, we do it! Most people actually love to have a very clear goal to work for, they just hate planning (especially creative people!). Goals can be anything from “Get this feature to work”, “squash these bugs” or “write this blog post before Friday”. What people (especially creative people!) hate is unnecessary meetings. By using the ABC-method stated in the previous blog post, together with the following sprint recipe below, we have managed to define clear goals with our development, establishing what needs to be done to reach them and how much resources we’re burning to get there! All this helps to keep meetings to a minimum each week.

For more than six months we tracked progress made on Lake Ridden. Each Friday when we closed the week’s sprint we sat down and everybody could rate “progress” they felt they had done during the week. We had 10 categories and a number between 1 to 10 was assigned to each area. This is by no means a perfect process but it did indicate the feeling of progress (or lack of) the team was making each week. Seeing your progress and sharing it with the team is a very powerful way to increase morale and maintain a good velocity.

We also incorporated a section for “stress” into this check-up. For what good would it be to score high on progress if it also meant we scored high on stress? On Friday, each team member shares a number between 0 to 5, depicting how stressful they feel their overall week has been. Five means you are having acute symptoms of stress, like headaches, lack of sleep, mood swings, elevated pulse etc.

The Estate in Lake Ridden to the left, and then 6 months later on the right (still work in progress). Progress is not worth much if it exhausts the team, that’s why everyone is asked to rate their stress at the end of each sprint.

The Estate in Lake Ridden to the left, and then 6 months later on the right (still work in progress). Progress is not worth much if it exhausts the team, that’s why everyone is asked to rate their stress at the end of each sprint.

As a project manager, this method gives me something tangible to work with, a spreadsheet with clear numbers! If I see that someone has been having fours the last two weeks in a row, I know I need to take action to make sure this team member does not exhaust themselves.

Writing down the stress levels inside a team is a good thing since the very nature of stress is that it makes you forget how stressed you might have been last week or the month before that! You convince yourself that the stress you’re right now feeling is temporary, and that next week will be much better. A lot of game developers are like huskies, they absolutely love their job, and will draw themselves to death if you let them. We do this stress rating together and it’s shared with the whole team. This means that we can’t hide away someone’s stress, we’re in this together and we can support each other.

As I wrote about before, science seems to be indicating that brain heavy work, such as game development, might be the kind of work that would benefit from less time in the office. We wanted to experiment with this. After the summer we cut working hours to 7 hours in the office (+1-hour lunch at noon). Everybody comes at 9 and leaves at 17. Since we had tracked progress for the past 6 months we believe we had the perfect environment to experiment in.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Creating an environment where people don’t have to crunch or stress is something we’re trying our best to do at Midnight Hub. It’s not possible to eliminate stress to 100%, but being aware of what causes stress is an important component to increase the wellbeing of your team!

Creating an environment where people don’t have to crunch or stress is something we’re trying our best to do at Midnight Hub. It’s not possible to eliminate stress to 100%, but being aware of what causes stress is an important component to increase the wellbeing of your team!

After tracking progress for three months, we noticed the perceived level of progress was elevated, compared to before the cut, and the levels of stress maintained at the same level or lower. The only time we pull overtime has been building demos just before big events like GDC or EGX, and even then the reported stress levels have been around 2-2.5 on average!

Stress and crunch are a bit like your ulti-ability when playing games. It’s an extremely powerful thing to activate (that response was created by evolution to enable you to fight lions or run away from angry bears). But it has a very real cost on your whole body. Only activate it when it’s absolutely necessary. It’s not realistic to eliminate stress entirely when working in the games industry, but you can strive to create an environment where you’re aware of the costs.

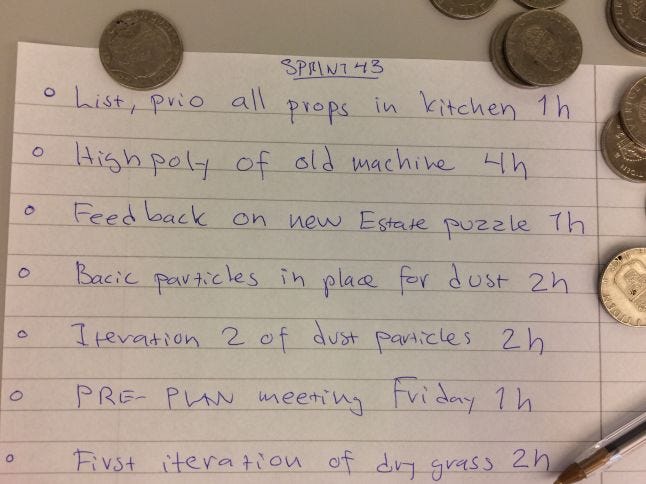

When estimating time, some teams choose to run with Scrum, to assign points to tasks depending on how complex they are to solve. At Midnight Hub we have chosen to implement a really straightforward method to help the team identify what needs to be done (the ABC-method) and then using real-world coins to help estimate how long something takes to do. One coin = one hour.

A week at Midnight Hub is 5 x 7 = 35 hours. During a normal week, roughly 5-6h go into meetings and 2 are used for misc (going to the dentist, having a rough day, bugs that pop up etc). This gives me as a producer 27 hours development time for each team member. Hands-on, undisturbed game development time. We literally have 27 coins at the office to symbolize this, and they are used each Monday when we plan the upcoming week’s work together. When we have listed all tasks that need to be done this sprint each member gets to distribute their own 27 coins.

When the coins have been placed on the tasks we don’t ask “do you think you can make this is in X hours?”. No, that often triggers people to say “yes” since they don’t want to look bad in front of their group. Instead, ask “do X hours seems like a reasonable amount of time to do this?”. This way of phrasing the question involves way less pressure on the person asked to perform the task, encouraging them to give you a more honest answer.

At Midnight Hub we’re using real-life coins to help us guesstimate time for different tasks. This helps the producers reality-check that no one is asked to work overtime or ha too much on their plate. It also helps if you need to time-box something. Perhaps you only have 2 hours to assign for making an icon or an item, before the artist has to move on to the next task.

At Midnight Hub we’re using real-life coins to help us guesstimate time for different tasks. This helps the producers reality-check that no one is asked to work overtime or ha too much on their plate. It also helps if you need to time-box something. Perhaps you only have 2 hours to assign for making an icon or an item, before the artist has to move on to the next task.

Using coins like this is a way to more or less force people to think hard about what to prioritize. It also makes it very clear that you can’t just ask somebody to “fix that thing during the week”. If someone has distributed all their 27 coins and you then ask them to do even more tasks, it literally becomes like asking someone to spend money they don’t have. This way everyone’s workload is reality-checked.

This system is a bit more challenging to use if you have a team of junior members that are not used to guesstimate how long it takes for them do a certain task. That’s when you need to have an experienced developer’s input on how long something usually takes, or you simply have to timebox something. Maybe this character for the new DLC has to be ready at the end of the week, then you might give it 27 coins and that’s it. But as with everything in life, the more you do this, the better you get at guesstimating!

This system only works when people are being honest. Encourage your developers to estimate bad scenarios where things take a lot more time. If it turns out they completed something faster than they anticipated, make sure to have bonus tasks to distribute. It’s also important to remember that you need to communicate to the team why this is system is a good idea. A lot of developers hate estimating how long something takes because they feel like they commit to that exact number, and if anything suddenly turns out to be a can of worms they feel trapped, since they promised to complete the task in a certain amount of time. Ensure them that this is a guesstimate, that you’re not holding them accountable.

A lot of developers “just want to get to work, not talk about working”. If you’re a project manager you need to tell your team why you’re doing this, what the benefits are and ask them to try it with you. Tell them you’re going to try this for a month, and if people don’t like it then you can always switch back to the old system after 30 days.

As stated in the earlier blog post, our leads have chopped the whole game into A, B and C sections, along with all important deadlines and inserted tasks like QA, trailers, translations etc on a big, real-life calendar visible to all in the office. Each Friday morning management invests one hour to reality-check this big master plan. Do we need to change anything or do we have new info that can help us plot out even more details? We call this Pre-Planning. This routine helps us stay on track and bring an updated planning to each sprint meeting with the rest of the team. Time spent planning is time spent NOT wasting time or throwing away stuff people have already made.

We run this project in sprints, starting on Monday morning at 9, ending on Friday at 16.

Monday Morning:

Check-in. Everybody takes a minute to write down what they are thinking about. This could be ANYTHING. We go around the team and people can share if they want to. This is a good method to get people into work-mode and sort their thoughts.

Check this month’s roadmap together. What should be done this month according to the master plan?

Play the in-game parts people will work on. This makes sure everybody is on the same page, that everybody has a fresh memory of the game. A good way to eliminate misunderstandings and get up to speed on what needs to be done in this sprint!

Consult the ABC-recipe. The team starts to sync within itself, talking about how to do things etc. Leads and seniors might need to lead these discussions or get them going.

Write down personal task cards for the week to come. The project manager goes around the team and writes down clear cards on what everyone will be doing.

Allocate time for the tasks! This is when each team member distributes their 27 coins on the tasks in this sprint.

The project manager digitalizes this. We’re using Favro, but programs like Trello works just fine for this. Or just use post-its!

Team members individually chop down their big cards into smaller lists within Favro.

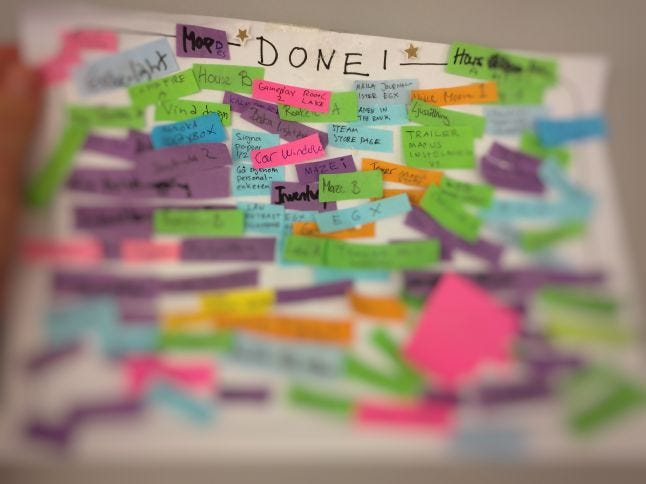

Each Friday we check our progress and what was finished. We then move the task from our big calendar to the DONE-board, seen here. This is something the whole team enjoys!

Each Friday we check our progress and what was finished. We then move the task from our big calendar to the DONE-board, seen here. This is something the whole team enjoys!

Friday Afternoon

Check-in.

Rating stress-levels. Everyone gets to say something about how the week has been. We document stress levels.

Move tasks to the “DONE” board. This is a thing that really increases motivation!

Check the upcoming roadmap together. This roadmap was groomed in the pre-planning, remember? We talk briefly about what we’ll be working on next week. This helps people get up to speed on Monday morning.

Positive Show n’ Tell. We gather around one computer and everyone gets to show 1-3 things they did this week. This basically means playing different part of Lake Ridden together. We focus on positivity.

We do The Square. The Square is when we briefly talk about if there is something we:

1. Should be doing less of

2. Should continue doing

2. Something we should stop doing

3. Start doing

Digital cards are archived and everybody goes home!

Each Friday we do The Square! We do a small retrospect on what we should keep on doing, what we want to start doing, if there’s anything we need to stop or do less of.

There are countless ways of running a game project, and what might work for us may not work for someone else. We have experimented, improved and made a lot of mistakes to arrive at this system, and I expect it to change even further as we’re about to reach the final stages of production with Lake Ridden. This system is made to help the team know WHAT to do, WHEN to do it, to avoid burnout and to encourage communication and honesty. I believe there is a way to make games that do not shatter people and make them leave this industry.

When making games you need to think about the resources you are burning; time, money, physical toll, brain power, and morale. Different tasks eat away different amounts of these resources. One way to keep your eyes on the ball is to use real-life cold, hard coins when you estimate the time something will take to do. One way of figuring out what to do can be to use the ABC-method together with sprints and reality-checking your master plan/backlog each week on a pre-planning meeting.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Our game has been chopped up with the ABC-recipe to make it easier for the team to understand what should be done and when.

Our game has been chopped up with the ABC-recipe to make it easier for the team to understand what should be done and when.

We still have to release our first game as a team, but I’m very positive we’re on to something exciting! I’ll update you after the release to see how this worked out! No plan survives contact with reality : ) If you’re curious about Lake Ridden you can visit our Steam page here or follow me on Twitter! Thank you for reading this far!

Cheers,

– Sara, producer and studio manager at Midnight Hub

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like