Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Market consultant John Andersen steps up to Gamasutra's virtual soapbox in today's feature, and explains the lack of adequate copyright protection for classic Japanese games, and the subsequent ability for publishers to infringe on them unscathed.

There is a serious legal issue in Japan with video games – old and new. Just this past year I've had to inform a number of different Japanese video game companies that their copyrights were being infringed upon. These infringements involved classic video game properties being sold or used overseas without license or permission. The Japanese companies I dealt with have been in the business for years, some are large corporations, while others have no overseas operations or have scaled back game development entirely.

One such copyright infringement case I uncovered involved a U.S. company that had the audacity to wipe the original publisher name and copyright year off the title screen of a game they were selling. This same company also took another Japanese game and replaced the original publishers logo with theirs claiming ownership in order to look legitimate. They knew they were selling unlicensed game properties from Japan and just had to cover their tracks.

It just so happened that these unlicensed games had out-of-date copyright and trademark filings, and were owned by companies that did not have operations outside of Japan. This was a weakness the violator thought they could exploit and get away without being discovered, but they were wrong.

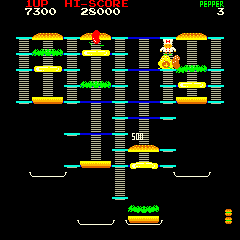

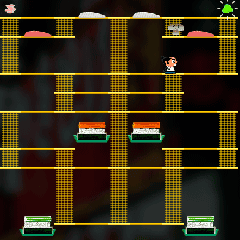

Then there is the case of the CBC Network. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation receives just under a billion dollars a year in federal funding along with revenue from TV advertising. The network currently operates "Cbc.ca/kids", a website aimed at children with Flash versions of games that visitors can play. Their "classics games" section features X Attack, a clone of Space Invaders (Taito) and Matrix Moon Mayhem, a clone of Moon Patrol (Irem). Another notable entry in their "action section" is Sushi Samurai, a clever clone of Burgertime (which was previously owned by Data East but then sold to G-mode, a Tokyo-based cell phone content company).

G-mode's Burgertime (left, 1982) and CBC Network's Sushi Samurai (right, 2006)

Yes, that's right, federal Canadian tax dollars are funding Flash clone development of video games originally created by Japanese companies. Some may argue there is no harm done since these games are not being "sold" for any monetary value. That's wrong. The CBC is still selling their TV programming to website visitors of all ages.

Meanwhile, the original Japanese copyright owners aren't receiving any credit or financial compensation for their work. Their property loses value and also gives users the insinuation they may also clone or copy any video game property they wish without consequences. It's important to note that G-mode, Irem, and Taito, along with many other Japanese publishers, do not maintain North American offices to combat illegal use of their games.

The legal department of Taito was contacted in preparation for this column to ask how they felt about the Space Invaders clone of X Attack on the CBC website. The legal department of Taito released the following statement to Gamasutra:

We have taken necessary steps to prevent the game entitled "X Attack!" from being on the CBC children's web site making use of your information.

So, the verdict was in, Taito is none too pleased to see a Space Invaders clone online.

It's unfortunate that the CBC can't bring more creative originality to its Flash games. There is a fine line between being inspired by a game, and to cloning it altogether. It's ok if a plumber named Mario collects coins and a hedgehog named Sonic collects rings, but a problem arises when very specific creative contributions such as layout design, character design, object placement and movement are clearly identical. Secondly, games such as Burgertime and Space Invaders have been accessible for more than 20 years, through numerous coin-op and console versions, so it's not as if they're unknown.

Taito's Space Invaders (1978, left) and CBC Network's X Attack (2006, right)

How these Flash versions passed by CBC legal personnel and management remains unclear. Video game copyright and trademark infringement is not just being committed by corner store operations, but by legitimate corporations. It has potential to damper business development between international publishers. It says to the original authors in Japan, "We don't respect you or your games, even though we can pay for licensing".

A company or person will never forget when they've had something stolen from them. They'll never forget when they've had a copy of their creative work cloned, copied or bootlegged. Let's not forget that it hurts the bank account, and can even discourage product and business development altogether.

Roy Ozaki, president of Tokyo-based Mitchell Corporation knows this all too well. His company is responsible for Polarium on the Nintendo DS. In a January 2006 interview with Chaz Seydoux of Insert Credit, Ozaki commented on his copyright infringement allegation against PopCap Games. The allegation was that PopCap's Zuma was a clear infringement on Mitchell's Puzz Loop. Ozaki makes his feelings quite clear:

"My lawyers in Japan are supposed to be on this. Progress is slow because if we do court battle in US, we would be at a disadvantage. You know the Americans and their mentality. We will be up against American jurors. You know how biased they are towards Oriental companies.

Popcap games' lawyer replied my mail and the one from my lawyers' office. In essence, they don't give a shit. I think they knew what they were doing from the start and they are bad businessmen. You know that to think of a game and to actually make it takes a lot of energy and money. Ripping off someone else's idea is bad; they don't belong in the game business."

[We contacted PopCap CEO Dave Roberts regarding this issue, and he commented simply: "There are no pending lawsuits from them to us. They have certainly told our partners about [the similarity] many times. Our position is that we haven't broken any laws." He also noted that PopCap "does distribution in Japan now, too - so it's not like we're not in Japan." Roberts declined comment on the whole 'clone wars' issues in the casual game space, for which there are notably a great number of clones of Zuma, other than noting in general of PopCap's attitude to perceived 'cloners' of its games: "We are not known as a company who resorts to legal tactics."]

Mitchell Corporation's Puzz Loop (left, 1998) and PopCap's Zuma (right, 2004)

Many games can still bring in revenue through new formats and services, from cell phone versions to online subscription services. This has been proven. Yet, sadly, some games from Japan aren't seeing the light of day as they've been labeled "too old" by company executives, or sadly forgotten altogether. This opens the door to potential bootleggers, clones, and copiers.

Even if a Japanese game developer or publisher does not have the resources to devote one single company website page to preserving that game, its creation should at least be legally documented. That documentation should take place at two key offices: The United States Copyright Office and the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Why the United States? As some are well aware, these two offices maintain their own searchable online databases, accessible from anywhere in the world. The trademark database is especially important since an entry will list a company name and contact address. This is an important business contact tool. As unbelievable as it sounds, I've spoken to some in the game industry who are unable to find Japanese copyright holders for many classic games. In some instances, with the passage of time, employees, and disposal of contracts, some Japanese companies may not even know what they own! That's how bad it is. Publishers have to account for each and every game in their library.

Every game developer and publisher, large or small, Japanese or not, should file legal documents for their games with the U.S. Copyright and U.S. Patent and Trademark Offices. When a video game property is sold to another entity, or if a license reverts back to its original owner after a period of time, a "Transfer of Ownership" statement should also be filed. All of this effort accomplishes three objectives: It preserves the hard work coming from a video game development team, it serves as a back-up in the event litigation will need to pursued, and more importantly gives integrity to the industry as a whole.

[John Andersen is a North American market consultant, and specializes in providing overseas business strategies for Japanese video game publishers and developers. Andersen recently consulted for G-mode, a Tokyo based cell phone content company, and contributes news features to various video game news outlets.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like