Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

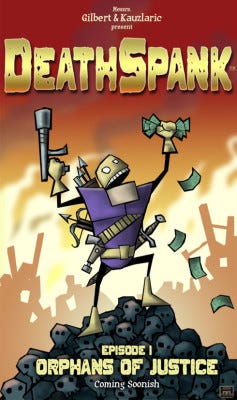

Ron Gilbert is best known as the co-creator of Monkey Island and Maniac Mansion, and he's returning to games with the episodic DeathSpank - and, as Gamasutra finds out, strong opinions on how the game biz needs to evolve.

Game designer Ron Gilbert is best known for his crucial role in classic adventure games at LucasArts, where he co-authored the SCUMM graphic adventure tool and birthed seminal releases such as Maniac Mansion, the particularly fan-beloved The Secret of Monkey Island 1 and 2, and Day Of The Tentacle.

Following his co-founding of Humongous Entertainment, which had notable kids' game success with the Freddi Fish and Putt-Putt titles, as well as his nurturing of Chris Taylor's Total Annihilation at sister firm Cavedog, he stepped back from those firms and into a consultant career.

More recently, he has been thrust back into the spotlight, in a small way, thanks to the success of Hothead's recent Penny Arcade Adventures for the PC and Xbox Live Arcade, which he worked on and which transforms the popular web comic into an episodic adventure/RPG. His own DeathSpank - based on an online comic he helped create - is now confirmed to be Hothead's next episodic game project.

Gilbert, in fact, is a major supporter of episodic gaming, and here talks about his role as creative director at Hothead Games, his belief in that format, bringing back lapsed gamers with these games, and how the Hollywood production system might just be inevitable for the video game industry.

What have you been up to the past couple of years?

Ron Gilbert: The last couple years I've been doing a lot of consulting; I do a lot of game design consulting with companies. I've been consulting on those Penny Arcade games that Hothead is working on. I've done some consulting on a large MMO that's yet to be announced.

I've been doing a lot of that, but I think the main thing that I've been doing is working on the game design for DeathSpank. I've been working on it for probably close to four years. But it's just kind of been this background thing, which both Clayton [Kauzlaric] and I have been working on.

And what is Clayton's role, exactly? He, obviously, works with you on the comics on your blog, but how did you get involved with him, and what exactly does he do on the project?

RG: Well I've known Clayton since, probably, 1996. He used to work with me at Cavedog, and he was the lead artist on Total Annihilation, and he was the lead designer on Total Annihilation: Kingdoms. And we're just great friends, and we've always done creative things together, and we decided to do these little animated comics on my Grumpy Gamer blog.

So Clayton and I just worked on those, and I did some of the writing, and he did the art and animations for them. And one of the characters that was created for the comic was the character DeathSpank. He was kind of a parody, and a satirical look at games' heroes, and how seriously games seem to take them.

And so he and I just created this character, and as we created it, we started to think, "You know, he'd be really fun in a game." So we just started working on some game designs, and story, and building up this world. He and I have just worked on that together.

Is he actually out there at Hothead with you?

RG: No, he's the creative director at Gas Powered Games right now. So his involvement is just kind of casual, and we continue to talk about stuff and work out story and designs, but he's not involved with the project full-time.

At Hothead, I assume you're involved in a sort of general sense with the company, in addition to your own projects, since previously you were consulting already on the Penny Arcade games.

RG: Yeah, I'm the creative director here, as well as running the DeathSpank project. So, here, I oversee all of the projects from a creative standpoint: working with the designers, brainstorming with them, and helping them out whenever they need my help, and dealing with external projects that might come in, and those types of things.

So as far as your project goes, do you want to just give a run-down on what that's all about?

RG: Sure, sure. DeathSpank is an episodic RPG that's been described as a combination of Monkey Island-style storytelling and adventure, kind of melded with a very light Diablo-style RPG gameplay.

RG: Sure, sure. DeathSpank is an episodic RPG that's been described as a combination of Monkey Island-style storytelling and adventure, kind of melded with a very light Diablo-style RPG gameplay.

DeathSpank is a kind of over-enthusiastic hero that often does more damage than he does good, when he comes in to help people out with things. And, as his name suggests, the game's really a satirical look at gaming's heroes, and how seriously games tend to take them. I just really wanted to poke fun at that kind of stuff with him.

How contiguous are the episodes going to be, from release to release? Is it one overarching story, or will the episodes be more independent?

RG: Each of the episodes is very independent. There is some larger story context going on, but the story episodes are very short little completely self-contained stories.

They're really meant to be played in any order - you could play number five, and then play number one, and then play number four - so the order you play them is really kind of irrelevant.

What led to the Diablo influence?

RG: Well I think it's because, mostly, I love Diablo. I've played lots, and it's been a style of game that I've really liked. And it's kind of strange, because I really have not found a game since Diablo that I really have liked playing; you know, that kind of action RPG stuff. They did so many things so well with that game, and I think a lot of people have come along and tried to imitate them, and I think they've really missed the core of what was fun about that stuff.

I know what you mean.

RG: I'm also a big WoW player, and I really like that kind of structure of games. I like that whole "paper doll" thing, where you build up characters, and put equipment on them, and give them new weapons. That's just a lot of fun, and kind of why I wanted to do that. And I think that kind of stuff could meld really well with an adventure game, because I think those two play modes really complement each other well.

So why did so many publishers disagree? What was the deal? What happened there?

RG: I think a couple of reasons. One was, I really wanted to do it episodic. And a lot of publishers just aren't set up to do episodic games; they just don't really understand the economics of it, they don't really understand the distribution of it, they don't understand it creatively. And since I really wanted to do this episodically, I think that was a big stumbling block.

The other reason was, I think, the name, definitely. I think that it put people off; they didn't understand it. And to me, it's like, he is DeathSpank. He has to be called that, because of who he is, and what the games are like, and what they're poking fun at; it's very important.

It's a very overtly video-gamey name.

RG: Yeah, exactly. And, I think the third reason, and probably the most important one, is that I didn't have a demo. I think publishers are so reliant on seeing a demo before they do anything, that it's very hard for them to make decisions unless they can see something.

And I don't think that's inherently a bad problem, but what I think is a really bad problem is that publishers won't fund those demos. They expect people to go out and totally make them on their own, and I think that's generally bad for the industry, that that happens.

Do you think that has a long term impact, creatively? Because it seems like you could have designers experiment in broader genres or concepts if they didn't have to rely on these massive, set team structures every time they wanted to at least think of an idea for a game.

RG: Yeah, I think it does. I think what you find is, really, the only developers that can really get products pitched, are developers that have very large, established studios; where they can actually dedicate a team for six months to put together a demo to wow a publisher. And I think that's putting a lot of burden on developers that I don't think is really fair.

Image courtesy of Grumpy Gamer Comics

I think the publishers, first of all, should be able to look at a written design or a verbal pitch, and go, "OK. You know what? That's kind of interesting. We're going to put a couple hundred thousand dollars behind this, and see what comes from it." But they're really just not willing to make that kind of an investment, and I think that's too bad.

What are your thoughts on the Hollywood sort of system, where you have individual creative people who assemble into teams for the purpose of a project, and they have people that they often work with because they know that they work well with those people, but they're not in a defined, "Here's the 40, 50, 100-person development studio." Do you think that could ever work for games? At least for certain games?

RG: I think that it will. And I think that, ultimately, it has to. And I think we will shift to that model, but I think that there are a couple of things that have to happen before we really shift to that. One is that I think technology has to settle down a little bit. I think technology is moving forward really rapidly, and part of what a lot of teams do is exploring new technology, and I think that's kind of hard to do with an ad hoc thing.

I think the other thing that's going to have to happen - and this is a really big one - is we're going to have to become unionized. Because I don't think that you're going to be able to grab all of these freelance people when you need them if there isn't some kind of a union structure that's over the top of them. You can't really have a bunch of animators just floating around from job to job with nothing in between.

So I think there's going to have to be a lot more structure, and I think that's going to have to come in the form of unions - which, you know, I don't know that I really agree with that; I think unions bring a lot of bad things to gaming, but I think they're going to be necessary for us to move into that Hollywood model.

And I also think that game people are just going to need to get a bit better at scheduling projects, and planning projects, and hitting deadlines, and all these other things. Because I think if you're going to have a lot of contractors that are going to come in and go away, they really need to know when they're going to go away; because they're going to be booking other projects behind yours, and we're going to have to become a lot better about hitting dates. And I think the movie business, for the most part, they're damned good at getting their movies done on time.

As someone who covers the industry every day, it's sort of remarkable. When a publisher announces its initial release timeframe, it really is sort of a given that it's going to end up being one, two, maybe three quarters later. I mean, I always wonder why publishers don't just automatically assume games are shipping six months after they're announced - and then I think, "Well, how do I know? Maybe they already are taking that into account."

RG: Well I could tell you. I could tell you exactly why they do that.

Okay.

RG: They do that for financial reasons. Because they're trying to put together financial plans, and they have a board of directors, and they have budgets, and they have earnings, and they have all these other things.

So, I think a lot of them take that whole philosophy that it's easier to ask for forgiveness than permission. It's easier for them to put together a budget and a bunch of financials that look positive and aggressive, even if in the back of their head they just know the stuff's going to slip.

So this is the machine you were up against for the last couple years.

RG: Yeah, definitely. Yeah.

So you spent some time sitting at a desk at Double Fine, working on your pitch, and your design; what exactly did that entail?

RG: Well I spent two periods at Double Fine: I spent a period, maybe I think it was two or three years ago, where I worked out of Tim [Schafer]'s office for a few months; and that was really putting together the initial design in a sketch. And this actually wasn't for DeathSpank. This was for another game with the same gameplay, the same melding of RPG and adventure, but it wasn't the same story. I started just putting together a lot of pitches - you know, setting up meetings with publishers, you know, doing that sort of thing.

Then I went off and I worked on some casual games for a while with Clayton, and then I did some consulting jobs, and then I came back to Double Fine just a couple of months ago. But at that point I knew I had to deal with Hothead, so that was a much more focused thing, where I really wanted to get the design of the very first episode of DeathSpank completely done.

So I was very, very focused during the last few months that I was there, just cranking away on this design, getting the story written, getting the puzzle structures done, getting the RPG stuff all figured out, and I also wanted to write a couple other episode stories. So that's what I was doing the last few months, when I was working in Tim's office.

Obviously you're positive on it, but what are your thoughts on this whole episodic gaming thing that's happening? People seem to be cautious in getting into it, because it does seem to be a difficult schedule to maintain.

RG: Yeah, I think it is. And I think there are a lot of positives to episodic gaming. I think, for me, as a designer and a storyteller, I like being able to tell a lot of little stories. Being able to take a character like DeathSpank and just put him in many, many different situations, to me, is a lot of fun. And so, to me, that's one of the things that I really like about episodic gaming.

RG: Yeah, I think it is. And I think there are a lot of positives to episodic gaming. I think, for me, as a designer and a storyteller, I like being able to tell a lot of little stories. Being able to take a character like DeathSpank and just put him in many, many different situations, to me, is a lot of fun. And so, to me, that's one of the things that I really like about episodic gaming.

I think there are some other very positive things about episodic gaming. I think a lot of gamers are getting older, and they don't have as much time to spend on [gaming]. They're having families, and wives, and kids, and all these other things, and they still love gaming but the thought of picking up a game that's going to take them, you know, thirty or forty hours to finish, can be a little bit daunting and intimidating. So I think what they do is, they play games and then they never finish them.

So I think episodic gaming done right, like what Telltale, and the way that I want to do it, I think you can give these people very rich, deep experiences that are just shorter. And one nice thing about doing the episodic is, when I do a DeathSpank episode, I'm pretty damn sure that everybody's going to see the ending. Which means that I can actually focus effort on the ending of my game. When you're building a very large game, you put a lot of your effort into the beginning, because maybe only 20% of the people will ever see your ending.

So I think those are some of the things, to me, that are very interesting about episodic. I think the distribution is an issue; I think we're just starting to get really good digital distribution, and I think that's key to the episodic stuff being successful. So I think those are some of the hurdles.

I think some of the other hurdles, I think a lot of gamers still think that episodic is taking one big game and just hacking it up into pieces and then selling it to them. And I think that's just one of those things that time will fix, and when people start to play really good episodic games, they'll realize that it isn't a large game hacked into pieces, but they're actually short little games, and it's a very different structure; not only for the game, but the story.

It's a lot like television and movies, you know. A television series is not a movie hacked into twenty-two pieces; it has its own structure, its own way of telling the stories. And I think people will slowly realize that about episodic gaming, and they'll start to appreciate what it can give them from a gameplay and a storytelling standpoint.

What you mentioned about how only 20% of gamers will see the end of your game, it's remarkable how true that is despite the outcries from the certain, very specific, hardcore segment of gamers, which is demanding super-duper long games.

I was talking to Valve - this must've been like two or three years ago at this point - and one of the things that they said is that they can do all of their tracking through Steam about usage of their games so few people actually get to the end. And then a few years later they released Portal, which was this completely self-sufficient experience in a few hours. I'm wondering if you've played that, and what you thought of it.

RG: Yeah, I did play Portal. I think there were a lot of things I really liked about Portal. I think having the short game is great, although people bitched about how short it was, which is really amusing to me.

Yeah. That's true.

RG: But yeah, I think Portal was really neat. I think that whole gameplay mechanism was a lot of fun. I think the only downside for me, with Portal, was it seems like they had this really neat little kind of "technology trick", you know, with the portals; and it was really fun to play with that, and I'm glad that it was a short game, because I don't think that you could've sustained that for much longer. I was really not grabbed by the whole "sterile laboratory" environment of it all. I kept, in the back of my head, I kept saying, "What would Nintendo do with it?"

You know, if this was a technology that Nintendo had come up with, and they were going to produce a game on the Wii, where would it take place? What world would it be in? So I think they missed the boat, creativity-wise, with their whole world and their story and everything.

But, you know, Valve is a company very focused on the hardcore gamers; that is a great audience for them, and I think in trying to hit that audience, I think they did the right thing with the game.

Do you know if Hothead is going to try to do anything similar to what Telltale is doing, and build its episodic structure into a complete business model that can be taken to other developers? Telltale seems to really be trying to make that its entire focus in the industry.

RG: I think one of Hothead's big focuses is on episodic stuff. I don't know if it's necessarily "episodic" per se, but I think one of their big focuses is on, I guess you call them "lapsed gamers". These people who are really into gaming, they enjoy hardcore gaming, but they just don't have the time to invest in the stuff.

They're not 35 year old women who are interested in match-3 games. The whole casual game market, which to me is like, I don't even know if I consider that games, in a way, you know? So it's not really those people, but it's the people who have played hardcore games; they've played Half-Life, they've played these things, but they just don't have the time anymore. And I think that's really Hothead's focus, is really trying to get those people. And I think episodic is a very good first step for that.

On the topic of audiences that maybe aren't being catered to as much as they could be - because of your historical importance in the adventure genre, I'm curious what you think about it.

I have, honestly, quite a few friends who played a lot of adventure games back in the '90s, and when that genre started to fade... there are still a lot of adventure games being made today, but it's not quite the glory days that it was when it was you, and Tim Schafer, and Sierra, and Revolution, and all those guys. I feel like a lot of people who I knew, who played those games at the time, aren't playing games now, because they're less interested in just being another space marine. And I'm curious if you think that those gamers will ever be catered to.

One thing I talk about a lot is games that are easier for those people to get into, you know? Games that are still what we would call full games. They're not Bejeweled or something; you're still in a rich world, with a character, and you're controlling it, and you're making decisions, and you're exploring, and doing those things. But just with that greater focus on character and story. I'm wondering if you think that there's any mechanism by which those players will be able to find things that they enjoy again, or if the industry has moved on.

RG: Well, I definitely agree with you, that this industry has one too many space marine games. I'm tired of seeing that stuff, and I think there is no doubt about that. But I think you are absolutely right; there are just a lot of people out there that are being disserviced by the types of games that are coming out.

And you see that a little bit in the success of the Wii, because you don't have a bunch of space marine games on it; you have some things that are lighter, that are more fun, that are more creative, that are more visually interesting... Not "visually" from the "obsessed with technology" kind of interesting, but the "artistically" visually interesting. And I think the success of that proves that out, that there really is that audience, there.

And that is one of the things that I want to do with DeathSpank, and other episodic games I may make, is to do things that are a little more interesting and a little more varied, and to build some games for those people that did like those old adventure games. I mean, DeathSpank, even though there is this kind-of Diablo-esque RPG in it, it is very much an intricate, complex adventure game, much like Monkey Island was.

LucasArts' The Secret of Monkey Island

So I am hoping that I can build this, and that those people are going to like it, and come to it, but it also has some other stuff that people who maybe aren't into adventure games as much, because they are kind of slow and contemplative, that there's other aspects of it that they're going to get into. There is a little bit of adrenaline going on.

I think the key with DeathSpank is going to be to meld those two things together in the right ways, that they don't turn those two types of players off, but they'll actually enhance the whole experience. That's the challenge that I see with the game, getting those two things done right together.

This is always a really potentially dire question, but - what are your thoughts on the industry as it stands now, and the way everything is going? You're known as a fairly curmudgeonly guy; you run a blog called Grumpy Gamer. You've also got your project here set up, and maybe that's a new avenue that's opening up. What do you think about the industry in general? How's it doing, and where's it going?

RG: Well I think, generally, the industry is doing pretty well. I think it's on a really good financial setting, which I think is really positive. I think that as the industry can make more money, and be more successful, I think its reach will grow. And I think that, ultimately, will help indie games, and help games that want to be different.

You know, the movie industry certainly has its share of space marine movies as well. There are big blockbusters that are shallow, but they make hundreds of millions of dollars, and I think the movie industry is pretty good at taking that money and funding a lot of more indie movies, and smaller movies, and movies for niche audiences. And I think the game industry needs to move into that model.

There's certainly nothing wrong with Halos and Half-Lifes, and all these other things being out there. But I would like to see companies like Microsoft, and EA, and all these people take some of that, and really start to support different levels of titles. And I think if the industry continues to be financially successful, we will eventually start to see that; so I think that's actually a very positive thing.

And you know, when I started out in the industry, it was very, very niche. If you were not a hardcore game player, you knew nothing about games. But today, pretty much everybody you run into plays games at some level, and I think that's a very positive thing.

That's true. And that situation you described with the movie industry, that's an - I think we actually honestly may have talked about that, like three or four years ago, when we spoke for a little bit.

RG: Yeah, I think we did.

But it's something that I still harp on a lot, because I think it's so crucial in reaching this last group of people, you know, this fairly sizable group of people who aren't into games, per se; and I think it's finding that medium between the ultra experimental indie games - which I love - and the big triple-A, big-budget titles.

I feel like there's that space in the middle where you can still make reasonably ambitious, character-based, world-based games, but you aren't necessarily being held to the profit expectations that a Halo or a GTA or something is. And I feel like there should be fertile ground in the middle, and that's where so many great films come out of, and I feel like games could be the same way.

RG: Yeah. Total, total agreement with that. I think publishers, I think every single game that they sign, they're looking for it to be a home run. It's like every time they go to the play, they swing for the fences. And being able to hit like a single or a double is just beyond their comprehension, in a way. And I think they have to understand that that's important.

And I think that Hollywood does that, for a couple of reasons. I think one of the reasons is Hollywood sometimes funds these movies because they're cultivating talent. You know, they can see something in a director, or maybe in some actors, and they can put them in these films because they want to be able to help grow them.

And this is another area that I think the game industry is completely blind to; being able to take talent and give them games that are, you know, going to be profitable, but they don't have to be home runs, because they really want to cultivate that talent, and work with them in the future. And I just don't think that happens very much.

I think that also, to a certain extent, that there's also a certain issue of the games industry not entirely having figured out everything about the creative process. Like, It's sort of what you mentioned about a publisher looking at a design document, and being able to make a judgment call, at least on a relatively firm basis, whether this is worth supporting.

I think that the film industry, where the process is so understood, and it's become such a well-practiced art at this point, that when you have a director that has a clear vision, and you have a screenplay that is complete or relatively complete, skilled filmmakers are able to understand what that is going to be in the final process a little more easily than game designers are.

To be fair, games are far more fluid than films are, obviously. I mean, you're making a product that everyone will have a different experience with, guaranteed, simply because it's interactive. But I do think that there is some time to progress in really nailing down that creative process, and I feel like when that happens, there will be a more obvious line from concept to completion, and maybe some of those other avenues will start to open up.

RG: Yeah, total agreement there. I think one big advantage that Hollywood has on us is that generally they can read a script and they can understand what the movie's going to be. And one of the reasons is, I think scripts follow a very standard structure; every script looks the same, if you just flip through it from beginning to end.

Game design documents, you know, every game designer does game design documents differently. And it's very difficult for people toread through, and also what you mentioned, you know, that games are very fluid. Not a linear experience. It's something that players can screw up, they can meander around in, it doesn't necessarily happen in the same order... Just very hard to describe that structure.

One game that I - I'm just kind-of being a horrible shill for this game, but - I don't know if you've played No More Heroes, by Grasshopper Manufacture, it's on the Wii.

RG: No, I haven't.

It's, I think it's worth checking out, because it feels to me like it's in that middle ground. It's definitely a fairly ambitious exploratory game. It's a very combat-oriented game, and you're fighting these insane bosses, and it's very deliberately over the top, and pokes fun at videogame clichés, but it feels like it's that middle ground.

Capcom/Grasshopper Manufacture's No More Heroes

It's clearly not the highest budget game, but it still does a lot of those things that you expect out of a full game, and I imagine it won't need to sell as much as a comparable game would if they're giving the full 360/PS3 budget, but it can still find its audience with this incredibly strange atmosphere.

It's a crazy game, and one of the other things that I love about it is that you can really see the designer come through. Goichi Suda, the guy who directed Killer7. I think it's a big step up for him, from a gameplay perspective, but you can feel his style in the game, and that is something that is less common in games than movies, that is something that I would just love to see more of it.

RG: Yeah. I'll definitely have to check that out. Because it does really sound interesting; you know, serving that kind of market.

And I think, you know, the other thing you mentioned that's interesting, is being able to see a designer develop a style in a game. You know, you really can do it with a movie. I watch a Coen Brothers movie, and it's like you don't have to tell me, and I could tell you that's a Coen Brothers movie.

I think there's a whole debate about "Are games art?" and I think they absolutely are, and they really - when they start to be taken as art, and viewed as art, and even designed as art, I think we'll be able to tell who made the game just by the style sensibilities of it. You know, the gameplay styles, all of the artistic styles, and things.

I have to say one of the things I miss about adventure games is that it really was very heavily invested in that "designer at the top" kind of thing. I mean, if you play one of your games, the sense of humor is extremely recognizable; and if you play one of Tim Schafer's games, that aesthetic is very present; and if you play one of Jane Jensen's games, that hardboiled fiction is there.

And I feel like the adventure genre was ahead of the curve in that respect. Really giving the designer that big marquee slot, and it's too bad that that seems to have diminished in recent years.

RG: Well I think there might be some reasons for that. I think one of those reasons is that when we did Monkey Island, there were five people on that project. And, you know, not 150. And I think, also, as publishers put more money into things, they start to be designed by committee. And it's not even that the publishers are mucking with it, but even at the developer, you just have a lot of people.

My friends work in the business, and they work on some of these very large, high profile titles, and you know, I often ask them, "Well, who's the project lead? Who's the guy with the vision?" And they're like, "Well... It's just a bunch of us. And we sit around, and we all just really kinda figure it out together..." I think there's a lot of advantages to that, but I think that you lose that individual personal style that comes out in a game when these things are designed by committee.

And I wonder if the large budgets, and the large teams, and the lack of structure that I think a lot of games have... I wonder if that is what you're seeing more than anything else.

I do feel that, at least in many cases, games are a medium where you can have that level of auteurship, if you want to say it in that way, and design control. I do feel that there's room for that.

RG: I think there is too. I think that it's actually critically important that we have that. I mean I grew up in an era of that, with gaming, and it's just the way that I've always thought about them, but I think it's really important. I think it's really important that a game has the movie equivalent of a director; the person whose vision it is that the thing is becoming. I think that's really important.

Someone recently asked me if I think that the games industry is moving towards having more very visible representative faces on games - and they pointed to Jade Raymond, one of the producers on Assassin's Creed. And I was wondering if we're going to move more toward the direction where the producer, more than the designer, is the face. Because producers do seem to have so much influence on games; more so than on film.

RG: Well, I think what their titles are really isn't that important. I mean, we don't really have a set group of job titles in this business. I think that's one of the other areas that I think the unions have helped Hollywood out, is the title that somebody gets on a movie is really dictated by union rules. You know, you can't just decide, "Well, I'm going to call my brother the director, because he's my brother." If the director's union doesn't think that he's the director, then he's not.

And in the games business, you know, I don't really know what a producer does. You know, versus a designer. It seems like some people think of designers like they're a script writer; that they sit in a room, and they bang out a design, and they slip it through a slot in the door, and then a game gets made. And so I don't really know what the titles are, and it seems like a lot of producers - and I look at what they're really doing - they really are actually acting like the director of a film.

Yeah. That's true.

RG: Even though they have this weird name, "producer", which doesn't really seem to fit. I'd love to see titles just get settled out in this business, so when somebody says, "I'm a producer," or, "I'm an art director," or, "I'm a designer," I actually knew what they did on the project. And I really don't know that today. But it does seem like some producers are acting like the project lead for the thing.

Yeah, it does seem to be going that way. But yeah, "project lead", that's another one. Project lead, designer, director; I notice Japan tends to use "director" rather than project lead. So, what would you say - this is a silly question, but - what would you say your title is on DeathSpank?

RG: ...

Have you even thought about it? Have you even considered that?

RG: Yeah, I really haven't... I mean, I just always used "project lead", because that's just what we called them back at LucasArts. But see, to me, that is the director. It is the movie equivalent of the director; the person who has the vision for the thing, and sees the thing all the way through the process.

Speaking of project lead, how much leading have you done on this project? It's been a while, right, since you've actually been installed at a studio, in charge of a team, making a game from start to finish.

RG: Yeah. It has been a while. It's actually really nice to be around people again, as opposed to working alone. And that's one of the reasons that I called up Tim Schafer, and I said, "Hey, can you loan me your desk?"

I mean, it's not that I really needed interaction with the great people at Double Fine, but it was just nice to be around human beings again. And so that's been a lot of fun for me here. And I've got a couple of artists working on the project, and we're just having a great time going through and figuring all this stuff out.

This is a really goofy, kind-of VH1 type question... What is your relationship at this point with guys like Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman, who I know you used to work with so closely at LucasArts? I mean, how frequently do you talk to those guys? Or, what has that been like since you left?

RG: I'm really good friends with both Tim and Dave. You know, I see them quite a bit, and Dave has a monthly poker game that I come to, and Tim I saw a lot when I was working out of his office, but yeah, we're all good friends.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like