Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

In this second part, I will go over the pros and cons of the different kind of stretch goals seen in video games crowdfunding campaigns.

Last time, I went over how a campaign should plan its stretch goals and communicate about them, but I didn’t say much about the nature of stretch goals themselves. So it is time to discuss that.

And before I go into my thoughts on the topic, I think this requires an extra disclaimer. While I have a strong opinion about how stretch goals should be planned and announced, the nature of stretch goals is a much more complex topic, one where the nature of the game, the profile of its communities, the capabilities of the studio play such big roles that it would be hard for me to establish rules the way I did in the previous piece. For this reason, take all of the below as general guidelines and if anything feels inappropriate or odd for your own project, it is probably because it is and you should ignore what I say. On with it.

In your process to define your stretch goals (using wildly different scenarios as recommended in the previous article), there is something incredibly important to keep in mind all along: what are you trying to achieve with your Stretch Goals?

This might seem like an innocent question, but one too many project creators don’t spend enough time thinking about from my numerous discussions with many of them. Most of the time, Stretch Goals are seen as something needed to keep the campaign going, and you basically “need” them. And while they bring a much welcome boost to a campaign after reaching its goal, there are not that binary thing that magically get the pledges coming. They are a very important additional promises you are making, on top of the initial promise of delivering the rewards of your campaign.

So, what can you achieve with Stretch Goals?

Objective 1 – Get new backers to pledge for your campaign

Objective 2 – Get existing backers to pledge more for your campaign

Objective 3 – Get your backers to talk about your campaign (to get more new backers, but also to expand awareness on the project overall not just the campaign)

Objective 4 – Get media to talk about your campaign (a hard one to achieve)

Seems sensible enough, but you need to look at each and every one of your goals and ask yourself how each one of them helping the campaign?

You can go and incentivize your existing backers to upgrade their rewards through additional perks from the Stretch Goal. That’s a very common practice for miniature-based tabletop games, but a much more difficult one to execute for video games. However, if the game lends itself to this notion, this is great, because you are already actively engaged with the audience that those goals are intended for.

You can expand your game to make it attractive to a new audience. This is a very common approach and why you see so many Stretch Goals about bringing the game to Linux or to Mac. This is also the same logic behind adding new languages support. But. You need to make sure you know how you can tell those would-be backers about your plan. Most of your current backers won’t give a damn about the game being available on Mac and in German. They most likely speak English and want to play the game on PC.

Finally, you can build your stretch goals to be about the game content itself, and get your existing community excited about them. They might not be motivated to “upsell”, but they will sure be motivated to get the word out so more backers join you in order to get more “bang for their buck”. They become very motivated to play the role of advocates for your campaign and spread the word.

I have tried to break down those types of Stretch Goals with these elements in mind, this is what I came up to so far in terms of segmentation of stretch goals and the terminology I am using for each of them:

A Stretch goal that adds value to all the backers (or the very vast majority of them) by expanding/improving the main end project: extra levels, better music, physical component added as a bonus to everyone.

These should universally be appreciated by backers, and by players who missed out on the campaign as well. They are great tools to motivate your existing base to spread the word about your campaign once the goal was reached.

A Stretch goal that adds value to only a sub-section of the backers by expanding the main project in a way that will only benefit them: port to a new platform (Mac/Linux/consoles), additional languages added to the localized version of a game.

These are very paradoxical – existing backers already showed support for the game and these extra goals will not make them more interested in the campaign. If they have friends who care about a specific language version or a specific platform, they might spread the word to them, but it will only be a slightly less efficient message. Even the ultra fan, who will use every piece of ammunition you give them to get the word out will likely be less effective here.

A Stretch goal that adds value to the backers who increase their pledge, ie: additional content added to a new reward level or to a reward level higher than the most common tier, [for tabletop projects] additional miniatures only through add-ons.

This is most frequently seen with tabletop projects, where the extra manufacturing costs for the extra content more easily justifies the additional content to be dependent on new rewards, or limited to higher tiers of existing rewards. It needs a particular kind of game to do this elegantly. Expansions are sometimes use that way, with the extra content explicitly schedule post-release of the game, and the extra content coming at an extra cost, you can either pay for it during the campaign, or pay it at the release of the expansion. But an extra cost there is implied.

These goals are more complicated to communicate about overall, but they will be seen as added value to the project. If the game lends itself well for them, they can be excellent tools to raise awareness and money for a project. As mentioned though, they are not the most natural fit for a lot of games.

Extended content (straight additional goal) – Depending on the game, this will take different forms. It can be more levels in a platformer, more campaigns in an RTS, an extra character in a fighting game. The core here is that the game promised has a volume of content that is X, and the Stretch Goal promises to expand on that content beyond X. Everyone benefits from it, both backers and future players, but they can be very costly to put together and they are also not always a good fit for some games.

Consider Point-and-Click Adventure games for instance. While I can imagine a studio to be using this type of Stretch Goal to add an environment they never could fit in their original budget, it still comes across as completing an existing vision. Once the vision is set, expanding on it may not necessarily be what you want. Adding an extra 5h to that game could go against the well thought story that was initially pitched and dilute an otherwise great plot. More can be less sometimes.

I know this unusual here, but for once, I will discuss this with an example from Indiegogo, Keep Skullgirls Growing

Skullgirls was a fighting game, already launched, that went to Indiegogo to get funding to create one additional character to the roster of fighters in the game.

Once the funding for that one character was reached, additional goals were set to add… more of the same.

The campaign finished with 4 new characters added to the game, alongside more stages and voice packs. All content that has been added to the game, for every player (with some of that content to be purchased as DLC, but that’s not the point here).

The rhythm of the campaign was remarkable as the momentum was maintained very well, and the community strongly engaged throughout.

While it seems quite straight forward, the strength of that campaign from the incredible value the additional goals were bringing to the table.

Exclusive content (incremental reward goal) – Content added to the game, which is exclusive to the backers of the campaign. Quite a common occurrence for video games were variations of existing content can be easily produced, this becomes tricky when going into the realm of the gameplay-impacting content. And you enter a nightmare headache if you touch multiplayer with that extra content.

The recently launched (excellent) Armello had the issue with some of the extra content tied to Stretch Goals.

While they resolved the issue, it didn’t please everyone in their community, and it created unnecessary headaches for them I am sure.

Note that’s true for any exclusive content, not just the one tied to a Stretch Goal, but I have seen many times the content for Stretch Goal be less well thought through, making it more likely to promise exclusive content that would divide the game community.

Improved content (straight additional goal) – Taking the existing promised content, and making its quality better. It can take various forms, from an orchestra performance of the game music, to the hiring of a recognized name to write up some of the content, while also encompassing things like increasing the resolution of the art or the redesign of characters with the extra funds.

While weaker drives for backers, the end the result is a better game and something all will benefit from. This is also the kind of Stretch Goal that is easier to plan around, and less disruptive of an existing production plan (less disruptive, not non-disruptive though). Any kind of game can also plan for this type of improvement and I don’t think there is any studio out there that would not be able to come up with a few things they would like to improve on on their original plan.

Port to a new platform (segmented additional goal) – Taking the game, likely originally promised on PC considering the current state of crowd funding, and bringing it to platforms that were only speculative so far. While it’s very good to have for the studio and a worthy objective, this type of additional goal tends to be very weak. The existing user base is already committed to the original platform promised at the onset of the campaign. They will be able to play the game regardless. They might have an alternate platform they would like better for the game to be on, but that will always only be a portion of an already committed part of your backers, ie: they won’t spend more, they already backed you. They will want to spread the word about the game, but that will only be true for part of your backers (the ones that really want that extra platform and the ultra-fans who will use every piece of ammunition you give them to spread the word). Would-be backers who would like the game to be on their platform and didn’t initially back because of this will be harder to reach out. Some backers back at very low level on the chance that their platform becomes supported, but that’s not the most common behaviour. Press, unless you are a household name, will not cover a potential port of your game related to your stretch goal. You will already be lucky if they talk about your game reaching said stretch goal (in which case, it is good, but a bit late to help that specific goal to be reached).

I will break them down a bit here as they have different implications.

Linux and Mac. Because crowd funded games are on Windows PC, and there is a strong overlap on game genre with other computer operating system when gaming genres are concerned, there is always a demand for those two to be supported, either from the get go or as part of Stretch Goals. The vocal minority of Linux gamers on Kickstarter is actually quite impressive. And they will not hesitate to contact creators to let them know that they won’t get their money if their OS is not supported. It is all fair and fine, but creators need to really think carefully about the implication of supporting that vocal minority. More often than not, I have seen creators think that this would translate in more money than they actually got, or that that vocal minority would be equally present when the game would go on sales. The Mac community is a bit less vocal, but also a bit bigger when the game releases… At the end of the day, committing to this really depends on the cost to the studio. A lot of consideration need to be put there first, and maybe losing Linux backers in the short term is better than losing your sanity in the long term. It is definitely a consideration that changes with the scale of your project.

Consoles. There is a lot less demand for Console ports, but they do happen, depending on the game, and more often than not, this is driven by an aspiration from the studio. When you know you will want your game on consoles eventually, why not accelerate that by offering it as a stretch goal. With a few rare exceptions (yes, that’s a Yooka-Laylee pun, go ahead, sue me), your backers won’t care much, and this makes for a weak stretch goal as far as expanding your campaign goes. A frequent mistake as well, for small studios, is for them not to properly do their homework about what it would take to release their game on a console platform. Especially among a younger generation that is used to the App Store model where getting the permission to release on the platform is a formality, the approval process for Xbox or Playstation is foreign to them (see, I am not even mentioning Nintendo). I am not saying it is common, but it happens. And the other consideration here is that if you offer consoles as a Stretch Goal, you will build expectation for the rewards giving the game out will also give the game on those new platform potentially. Console manufacturers, in my experience, are rather open minded about this, but you will need to make sure they are on board, and the conditions they will want to distribute the game to the backers, before promising anything. This leads us nicely to the next category.

Mobile devices. Like for the other platforms, the fact that your existing audience probably don’t care too much about the game being on those new platforms is important to consider. Unlike the other platforms though, it is very likely a lot of your backers will own a game-capable mobile device and will see this as a “Hey, why not?” kind of goal. However, the real tricky part for mobile devices support is the distribution. Apple will not let you give away the game for free (or it will be free for all, not just your backers), it also won’t let you create a backdoor to unlock content that should be paid for, for free. Android is more permissive, but you will need to build your own system to support the unlock of your game, and distribution of the APK might have undesirable side-effects (like your APK ending up on Torrent sites or elsewhere). Moreover, the current system to buy codes for your own product on the App Store is… not very good (yes, that’s an understatement). Very often, this is not properly considered by project creators offering these devices as additional goals.

Overall, my experience is that porting a game to a new platform is an often offered Stretch Goal, but one that is not always properly thought through.

New Language (segmented additional goal) – Making the game accessible in more languages than initially promised. The game will likely be pitched in English, and the majority of crowd funding backers reside in Anglo-Saxon countries. We are not tracking these numbers anymore, but it was 80% of all backers, across all of Kickstarter one year and half ago. It is a lot. It is also very likely that existing non-Anglo-Saxons backers already on Kickstarter (and thus easier to get to back a project) are comfortable in English. Kickstarter is very actively pushing the development outside of English-Speaking countries, but truth of the matter stays the same, your core audience is likely decently fluent in English. If you offer extra languages as Stretch Goals, like for extra platforms, the existing backers are probably totally OK with the languages you initially offered, or they wouldn’t have backed you. That means you need to go and tell those would-be backers who were not interested in a game not in their language and convince them to join your for your stretch goal.

This is not as black and white as this, but there is a principle behind that remains important to consider. I will however give you an excellent (even if just anecdotal) use of more languages as Stretch goals.

The Mysterious Cities of Gold campaign is a bit of an unusual one. The campaign was not to finance the game, but to finance its port to PC.

When that goal was reached, there had been a number of strong demands for more languages support. Because the campaign wasn’t about the development of the game, the team had a limited margin of maneuver when it came to Stretch Goals. They were not going to add more content easily so went for additional languages, following the request of existing backers:

The first goal added 5 extra languages, bundled together in order to gather momentum: Italian, German, Portuguese, Brazilian Portuguese and Swedish.

Even more interesting, and to the team’s surprise, they had a lot of demand for an Arabic version of the game, as the original TV Show had a very strong presence in Arabic countries. The addition of that Stretch Goal was the reason one of their $6,000 backers backed that project at that level. He basically financed the entire goal by himself, because he really wanted it.

That’s always a nice example of listening to your community (as well as picking your fights when it comes to these decisions).

I think extra languages as goals are always a bit tricky – I am always more comfortable with them being bundled together with other goals to mitigate their very insular nature. And like for new ports, scale matters. A Stretch Goal that concerns 10% of your community will be a lot more efficient if said community is huge.

Physical content (incremental reward goal) – Creating new physical content, to be delivered to some backers.

The cas d’école here is certainly Shovel Knight.

As its campaign took off, a Stretch Goal was added that at $225,000, the studio would produce a physical game box, to be sent to all backers who had pledged $50 or more.

All existing backers under that threshold were suddenly incentivized to follow up on their pledge to get it.

While the data is difficult to check, the numbers from Kicktraq seem to indicate that this led to one of the best days of the campaign, but more interestingly, the best day in terms of the ratio for pledge per backer, indicating that indeed, a significant number of backers did upgrade to the higher tier for the box then. A successful maneuver if the costs were properly thought through).

There are different forces at play when considering the Stretch Goals. What a game studio wants to add (things that will help sell the game better at launch for instance) is not necessarily what the existing backers will be the most excited about (and they play a key role on spreading the word). A balance can be considered in mixing them up. Depending on the nature of a game, there are some additional digital perks that are relatively easy to add (and cost efficient), and looking at combining them with more dev-driven goals (new languages; ports) can help meet everyone’s goals.

The (aptly named) Foreign Diplomacy goal for Armello bundles together additional cards based on backers ideas to the game (clear cut straight additional goal) with additional languages support. Interestingly, this was changed during the campaign. It was initially just the extra languages. I don’t think this is a coincidence.

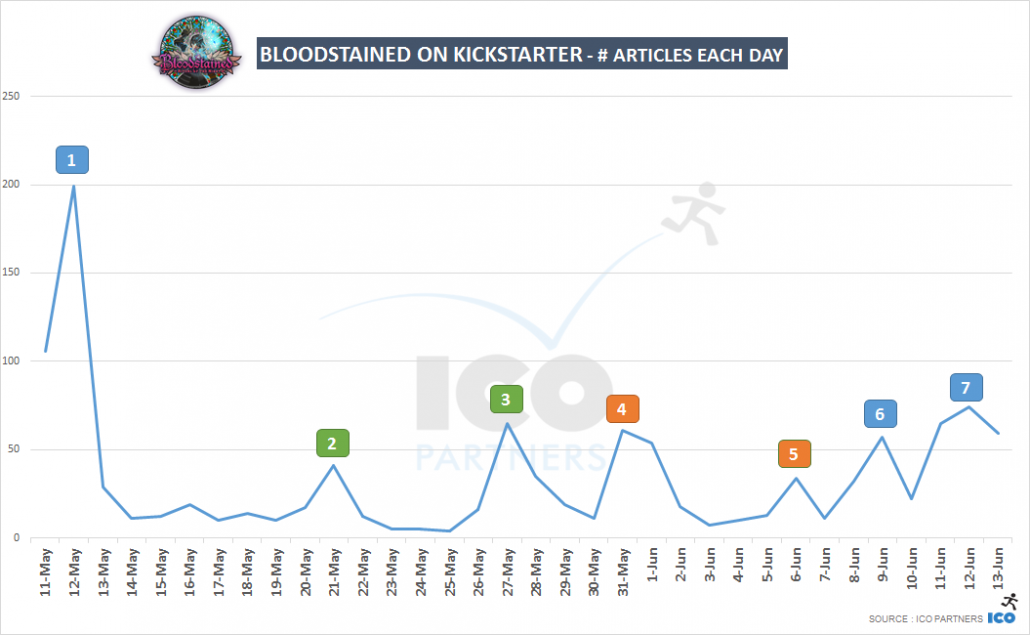

Listed among as my 4th objective for stretch goals at the beginning is to keep the presence of a campaign in the media. This is incredibly difficult, and to illustrate this, I went and looked at the Bloodstained campaign in our media monitor.

Keep in mind that at the time, Bloodstained was the most successful video game crowdfunding campaign ever, with a strong media presence throughout.

I have highlighted 7 high points of media presence there, and I will provide some background for each one of them:

This was the launch of the campaign. Very well mediatized, out of all the events, this was the most covered. Even the record breaking conclusion of the campaign didn’t come close.

The campaign passed the $2.5m mark and the “Biggest Castle” stretch goal is announced. This is the only “content” stretch goal you will see in this list.

The WiiU Port stretch goal is announced, and relayed in the media.

The WiiU Port stretch goal is reached, media cover this.

The PSVita Port stretch goal is reached, media cover this.

Streaming of actual gameplay of Bloodstained.

End of the campaign, at a record breaking level.

As a reminder, Bloodstained had 27 stretch goals in total. Out of those 27 goals, 3 resulted in significant increase in the media coverage – and two of them were related to the port of the game after the goal was reached. Certainly, the campaign benefited from the extra coverage those generated, but they were certainly out-of-synch with the priorities of the campaign.

Also, keep in mind this a very very well mediatized campaign, counting on coverage for any campaign beyond the launch and the success is being very optimistic (having both of those is already a victory). I always recommend to put the focus of the stretch goal to be around the community communication and have them helping the word-of-mouth first.

Treat stretch goals like mini-campaigns in themselves

Focus on what the community wants

Think through how would-be backers interested in them will hear about their existence

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like