Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Killzone studio Guerrilla Games went from its humble beginnings in the PC demoscene to become purveyors of one of PlayStation's biggest releases of 2011, Killzone 3. This profile revisits commentary from studio leaders to explore the history behind Guerrilla...

May 9, 2011

Author: by Hasan Ali Almaci

[Killzone studio Guerrilla Games went from its humble beginnings in the PC demoscene to become purveyors of one of PlayStation's biggest releases of 2011, Killzone 3. This profile revisits commentary from studio leaders to explore the history behind Guerrilla...]

One thing that is available in abundance in Amsterdam's 17th Century city center is history. Being a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the entire old city center is protected, and its history is preserved to the full extent Dutch law allows.

Most people who have visited the old city associate it with places like the Prinsengracht (Prince's Canal) that amongst its buildings has the Anne Frank house, or the Brouwersgracht (Brewers' Canal) which used to be Amsterdam's center of commerce, and which is generally regarded as the most beautiful street in the city.

For me, however, the associations are different; one thing that comes to mind when I see those old buildings is the Herengracht (Lord's Canal), named after the people who governed the city centuries ago.

For almost a decade at number 410, Herengracht, in a nondescript old building that used to be a bank, an unlikely story has played out. A small Dutch developer grew to become one of Sony's big first party studios.

The company's recent move from that historic building to a nearby modern office space prompted me to investigate the history of the company itself, and delve into both old and more recent interviews and meetings I had with key people at the company.

I am, of course, talking about Guerrilla Games.

"This place is falling apart around us," managing director Hermen Hulst once told me. "We have all the network cables hanging off the walls, the walls themselves are falling apart, and we lack enough electricity here to continue operating. Last summer we brought in a few diesel generators to run air conditioning, but this is a pretty exclusive neighborhood, and the people living around us filed noise complaints, so we had to stop doing that, [said] the police."

Yet it is not in this aging building that the story begins; to find the origins of what is now called Guerrilla Games, and what led to the Killzone franchise, we have to go all the way back to 1994 and even before.

In the late '80s and early '90s, there was a thriving demoscene -- a computer art subculture that started with crackers, who cracked commercial software, and added their own animated screens to the programs they hacked. From this, it grew to a legitimate subculture where coders showed their talents to the world. It still exists today. In 1991, a group called Ultra Force made the first ever PC 3D demo -- the so-called Vector Demo -- created by a single programmer.

The talents of this coder were recognized by an at the time new company in the U.S. called Epic Megagames -- and so in 1994, Arjan Brussee was invited to work on a project with a brilliant young designer. The game was called Jazz Jackrabbit, and the designer of the game Brussee worked on was Cliff Bleszinski, now of Gears of War fame.

Despite the fact that they are competitors now, the respect between the two men runs deep; when I asked Bleszinski if he will ever make another Jazz Jackrabbit game a few years ago, he told me that he can't do it without Brussee.

After Jazz, Brussee continued to do contract work for other companies, but his ambitions outgrew those possibilities. It so happened that in 2000, his company Orange Games merged with two other small Dutch developers (Digital Infinity and Formula). This brought in Mathijs de Jonge, who is now game director at Guerrilla. Hermen Hulst, meanwhile, was attracted as manager from an outside consulting company.

The merged company was funded and became part of the Lost Boys media group, owned by rich playboy Michiel Mol, who would later go on to start the Spyker Formula 1 racing team (which he sold to Vijay Mallya, and which today still exists as Force India).

And thus, Lost Boys Games was created -- a company that brought together the best developers in Holland and provided them with the funds to work on bigger and more ambitious projects.

And thus, Lost Boys Games was created -- a company that brought together the best developers in Holland and provided them with the funds to work on bigger and more ambitious projects.

Success early on did not come easy.

Said Mathijs de Jonge, "I have very fond memories of a Game Boy Color game we made during the Lost Boys Games days, which we sadly couldn't find a publisher for. Even though it was a Game Boy Color game, we had the same ambitions we had with Killzone 3, in a way.

"It's a puzzle platform game but it has a level editor built in, and all the 80 or so levels in the game we made with the in-game level editor. If you remember it, the Game Boy Color had an infrared port, so you could submit the levels/puzzles you made to your friends that way.

"That was already a big and ambitious project, and that was such a long time ago, and it's really sad we couldn't find a publisher for it -- because back in those days publishers wanted licensed characters, and asked us to change the nice characters we created to well-known cartoon figures. We didn't want to compromise our game, and sadly, that ensured that nobody wanted to publish it."

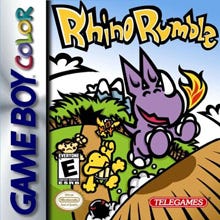

Learning from that experience Lost Boys Games went on to do contracted work, including Tiny Toon Adventures: Dizzy's Candy Quest, (GBC, 2001), Rhino Rumble, (GBC, 2002), Black Belt Challenge, (GBA, 2002), and Invader, (GBA, 2002).

After the release of these Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance games, Lost Boys Games was sold off to the Media Republic group, and renamed into Guerrilla Entertainment in 2004. This was likely done for tax purposes, because the Media Republic group was also owned by Michiel Mol -- so the new owner of the company was the old one.

It was shortly after the rebranding of the studio in 2004 that it released its first big console projects: ShellShock: Nam '67, published by Eidos for PC, Xbox and PlayStation 2, and of course the Sony-published Killzone.

The work the studio had done for Eidos was very much in line with the way it had previously worked on the Game Boy platforms -- contracted work for a third party publisher.

Killzone, however, was not.

"Back in December 1999," said Hulst, "we had made a demo called Marines. I showed it to Sony in London, and you have to understand back then that was a risky proposition -- since the only popular console FPS was GoldenEye. A lot has changed since then."

Given the market conditions when Hulst pitched the project to Sony, and the fact that Sony already had a promising sci-fi shooter slated for its platform, its decision to take a pass on the Marines project made sense.

On one hand, you had a small Dutch developer which had never produced a shooter before, and on the other hand was a well-known developer with a proven track record. Coming from the PC and Mac sphere, Bungie had extensive experience in making first person shooters (the Marathon series) and had two games pledged for the upcoming PS2 system.

One was a third person action game called Oni; the other one however is arguably the game that built the Xbox brand -- none other than Halo: Combat Evolved.

Bungie started out as one of the very few Mac game developers, but economic realities (the implosion of sales of Macintosh computers in the late '90s) forced it to branch out to Windows computers as well.

Halo was first considered for release on Mac, PC, and Dreamcast. As hype started to build around the upcoming release of the PlayStation 2, the Dreamcast version was shelved in favor of a console exclusivity deal with Sony for PS2 -- where Sony itself would act as publisher of the game.

Microsoft, however, was coming out with its Xbox and needed more talented developers to attract gamers to its first real entry into the console industry. Bungie was open for a buyout, and Sony lost the Halo franchise. It still got Oni via Rockstar, however.

Ironically, Halo: Combat Evolved -- the game that killed the Marines project for Sony -- was also the one that revived it. After the huge success Halo enjoyed on the Xbox, Sony realized it needed a high profile exclusive sci-fi shooter on the PS2. Guerrilla was contacted and the project got the greenlight -- and the budget it needed.

This, of course, fueled the fanboy flames -- with many, thanks to the pre-release hype, calling Killzone the "Halo killer". This, despite the fact that Guerrilla set out to make a different type of FPS, and despite the game's PR manager Alastair Burns, who left the company shortly after the release of the first Killzone game, telling me back in 2004:

This, of course, fueled the fanboy flames -- with many, thanks to the pre-release hype, calling Killzone the "Halo killer". This, despite the fact that Guerrilla set out to make a different type of FPS, and despite the game's PR manager Alastair Burns, who left the company shortly after the release of the first Killzone game, telling me back in 2004:

"Halo, you say? Well, we have the utmost respect for the people at Bungie; they made an incredible game. We are not trying to make a Halo, here, though. Yeah, both are sci-fi shooters, but I think that is where the similarities end. We are making our own game here, and I don't see why both can't be successful side by side."

Even after the game released and became a commercial success, controversy followed both the release of the game and the debut of its follow-up -- which exploded at E3 2005 when Sony's then-Worldwide Studios president Phil Harrison told us that what we were about to witness was all gameplay.

What followed were CG trailers of several games -- which Harrison had just claimed were actual PS3 games. Included was a Killzone 2 trailer, created by a Scottish CG studio.

This put Guerrilla -- which at that point was not yet owned by Sony -- in a difficult spot. Yes, the developers were working on Killzone 2, and yes, they had provided assets to an outside company to make a Killzone CG trailer, but the kicker was that Killzone 2 was up till then a PS2 project.

No code existed on PlayStation 3; in fact, Guerrilla didn't even have PS3 dev kits yet when development on the trailer started. After E3 2005, however, there was no way back for Guerrilla -- nor for Sony, who had backed itself into a corner thanks to Harrison's statements.

"After we completed Killzone 1 on PS2, for a good half-year or so, until early 2005, we had a PS2 game in development called Killzone 2. What happened was that we had never anticipated that that trailer in 2005 would get that much traction. I mean, the whole world seemed to be talking about it, and at that point it just made more sense to scrap the work we had done for the PS2 version and work on the PS3," said Hulst.

"You have to understand, back then compared to now, we were still a relatively small studio. I think we were about 55 people back then. So the decision was made to direct all our resources to the PS3, and try to fulfill the expectations set by that trailer. The trailer being gameplay was obviously not true -- because there was nothing there except for the trailer.

"The hard part for us was like 'Uh-oh. Now we will actually have to make that!' But the good part is that that 2005 trailer shown at E3 created tremendous focus for the team. You had a graphical benchmark, but also the intensity of the combat shown, and frankly there was no way back from that. When you show something and shout about it to the outside world, you better live up to it. So the good part of that was that it gave us a lot of focus, and it acted as a kick start for the project."

Sony realized that after the sky-high expectations that were created for the PS3 in the press conference, there was no way to not deliver Killzone 2 -- so the company decided to provide Guerrilla with the hardware it needed to make the game a reality on PlayStation 3, and also finally bought it from the Media Republic group in December 2005.

"Since Sony bought us we have become more professional," said Hulst. "As part of Sony's Worldwide Studios, we can get technical expertise from the other studios while maintaining our independence. Part of that is because of this huge pool of talent we have access to, and part because most people here are now on their third or fourth project and grew along with the company."

The first game released under Sony ownership was PSP title Killzone: Liberation, a third person action game within the Killzone universe. "Killzone on PSP allowed us to expand the Killzone universe into a different genre of gameplay; having created this IP ourselves ensures that we can explore and add to it ourselves in the future," de Jonge told me.

Then finally, after four years of developing the graphics engine and underlying technologies, the most expensive Dutch entertainment production -- including movies -- Killzone 2 was released in 2009 to critical acclaim. It currently rests at a 91 on Metacritic.

But the market continues to change. "Since we started making Killzone 3 two years ago, we have to anticipate those changes two years in advance," said de Jong of the developer's most recent release.

"If you look at all Sony first party games, they all have engines purpose-built for them; the technology becomes part of the DNA of your game. Uncharted, God of War, LittleBigPlanet all have aspects that can only be achieved with a custom engine," said Hulst.

With the underlying technology fully developed, Guerrilla managed to create an upgraded third core franchise game in under two years, and also managed to add a 3D TV and Move support.

"For Sony, 3D is a big deal, so for us to create a 3D experience that was strong enough to showcase what was possible in 3D was great -- and it was a great way for us to give back for the confidence Sony had shown in us," Hulst said.

"And it was the same with Move. You know, Move is something that we were excited about and can make the game feel more fluid, potentially, if you are up to it. We showed that off in the design of the Sharp Shooter [Killzone 3 Move gun peripheral] that we instigated here within the studio, and then we worked together with people at other studios and asked them for their input.

"We came up with designs, and asked other teams their input. Then Sony people in the U.S. made us a few prototypes based on our designs -- so within Sony, you are very much free to do that, to tap into the knowledge from the other studios and help each other out."

"If you look at our old games, everything had to be hand-coded; with our engine now, you can write a script and the engine will take care of it," said de Jong. "The shorter development time is because of that, and because the team has increased in size it was not that big of a problem. In the past deadlines sometimes slipped, so we wanted to prove this time that we can meet deadlines and ship at the intended date."

"For Sony this is really important, because they need to plan their titles spread out over the entire year -- so if a title slips, then the marketing plans slip alongside it, and that can then clash with the plans they have for the titles of their other studios. We didn't want that so we did everything we could to meet this deadline."

With the deadline met and the game in stores, it brings us to the end of their stay in the old bank. But the studio is now starting a new chapter that will add to Guerrilla's already rich history.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like