Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Two indie CEOs compare anxieties, strategies, and solutions to similar business development problems. They debate: What is the best way to keep your studio alive and relevant in today's market? Shoot for the stars or prune your scope?

Tanya X. Short is the Captain of Kitfox Games, a 4-person studio that created Shattered Planet, which released to Steam in July 2014. They are now in the process of developing Moon Hunters.

Guillaume Boucher-Vidal is the CEO of Nine Dots, a company that’s been running for 4 years with a core team of 6. They took 2.5 years to make GoD Factory: Wingmen, which released to Steam in August 2014.

At this point in time, Guillaume and I run similar studios. Both are aiming to create polished games with a relatively small core of people. Both are located in Quebec and are primarily centered around Steam as a distribution platform. Both have turned to Kickstarter for funding in the past.

The main difference between us and our studios is a gap in goals: Kitfox aims to remain small and keep their games similarly constrained, while Nine Dots has large ambitions -- they want to make big, AAA-competitive games, and grow the studio accordingly. Given a few years and a few more titles, our studios could look very different.

GoD Factory: Wingmen, Nine Dots' second title

I think of this conversation as a time capsule, showing what newish indie start-ups are thinking about, in terms of business development strategies and priorities. Undoubtedly as time passes markets will change and decay and blossom, but for now, this is where we are, here in early 2015.

Tanya: I started this conversation because I was curious. We were talking the other day about how lots of people are telling you that you should "refrain from big projects, go smaller, slim down the team" etc. You are super-resistant to this advice, and it seems like you've chosen ambition and a larger scope as one of your studio's strengths.

Guillaume: That’s right.

Tanya: Why?

Guillaume: A number of reasons. I think that there is currently a common misconception that it is sub-optimal or simply not viable to "think big" and to dare to jump into more ambitious projects with longer development time.

A business coach once shared with me an observation he made about most creative people and entrepreneurs: most of them are scared of undertaking a project that would be a full demonstration of their talent and ambition. They always keep the big project for later, waiting for the perfect context to do it. Which, of course, never happens.

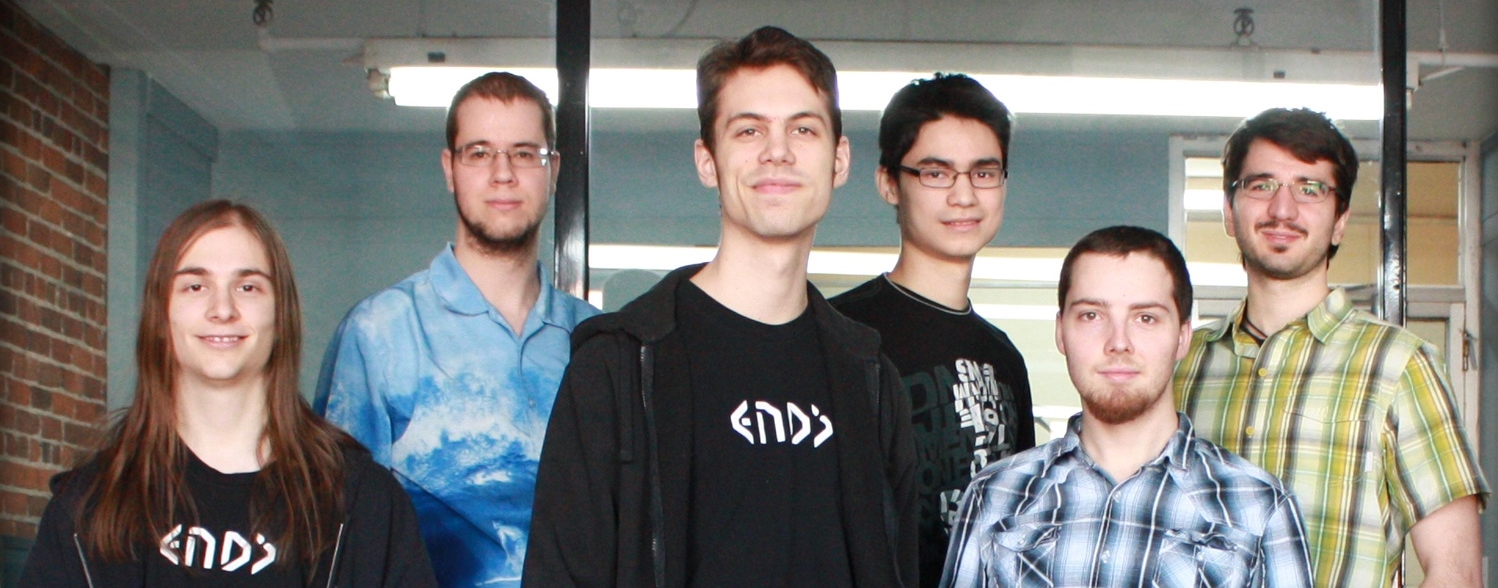

Nine Dots

I'd rather try and fail at doing something big and ambitious than succeed at doing something small, and I quickly found out that this was the case for everyone on the team. During the development of Brand, our pilot project, at first we were aiming at a development time of 6 months, as our goal was indeed to try "starting small", just like we had been told times and times over. However, I quickly realized that the team was not interested in making the game that Brand would have been if we only took 6 months to make it.

Tanya: Well, here’s where I confess that Kitfox is almost the exact opposite. We’re honestly scared of Moon Hunters, and somewhat wish we’d taken on a slightly smaller scope. The market moves so quickly, I don’t think anyone can predict a few years in advance. So if we can come up with a great game concept and quickly push it out there, we can have a chance of being ahead of the curve -- whereas if we sit on and nurture a big concept for years, someone else might jump in and beat us to it, or we might end up making something that feels outdated.

Plus, by staying can take advantage of little opportunities, like our current partnership with Concordia University's TAG program, which wouldn't be possible if we were bigger.

I'll admit we also recently took a small contract from Cartoon Network to create Steven Universe: Heap of Trouble, which was really fun. It's easier for us to squeeze in a month here or a month there on smaller opportunities where they come up, since we're "between projects" more often... and we all know how common it is for indie studios to need those little boosts to make ends meet.

Kitfox Games

Besides, as the project manager, I feel it's important that fewer things can go wrong. When there's fewer team members, there's a lower potential for drama or mishaps, and less time needs to be spent on human resources overall - hiring, contracts, management, etc. And with a shorter production cycle, a 10% slippage means we only add a couple of weeks -- as opposed to a couple of months, or god forbid years. We stay on schedule.

Guillaume: Is commercial failure of one big project really that much more of a risk than failing 2-5 smaller ones? Considering the current saturation of the market with small projects, aren't the odds of success a bit higher if your product rises above by offering something more ambitious and in tune with gamers' expectations?

Tanya: Maybe. I’d hope that the first mini-failure or two would be more educational, making the next few projects less risky. Maybe not. But all else being equal, let's say it's an ideal world and we each have all the money and stability and audience that we need -- we still have limited time on this earth. Time is the one thing we're not getting more of. So, as a mortal, wouldn't it be better to make MORE games, and learn more quickly?

Characters from Moon Hunters, Kitfox's second title

Guillaume: I do want to make many games throughout my career. But if I have to choose between making 100 games I would probably not buy myself or only 1 game I'd be crazy passionate about, I'd choose the latter in a heartbeat.

Besides, not everything we learn by doing small games is transferable to making bigger games. There are a lot of things to learn in terms of scoping, planning and designing bigger games that doesn't apply to smaller games and vice-versa. Marketing them isn't the same either and the audience might not follow you when your games change in scope, price point and complexity. So if making bigger games is what our team aspires to, I think our efforts should be made to steer in that direction as soon as possible.

Tanya: That makes sense. Though I find that specialising in smaller-audience, “niche” 2d games tends to keep the sharks away, as it were. It’s not just a matter of avoiding evil publishers – without multi-million dollar ambitions, the predators happily avoid us too!

Guillaume: We’re likely to self-publish too, but I think that spending more time on a project gives it a better chance to mature and to build traction. Spending a couple of years on a game will free some space to fine-tune its balance, pace, game feel and atmosphere. While it is possible to "nail it right" quickly, these are aspects you don't want to rush, and I believe it's generally helping to take your time and trickle down the progress until it's just right. Meanwhile, the extra time also means you have more room to find and interact with your audience. It gives you more opportunities to attend conventions, apply to contests, release trailers, do developer updates and send press releases until something sticks.

Tanya: Sure. More time building an audience is definitely always an advantage. More games, even relatively ‘small’ ones, now do that while the game is live. Whether it’s Early Access or just live operations, in some ways it’s easier to find direction when your players are guiding the process.

Guillaume: In the end, as cliché as it sounds, the important thing is to do something you're passionate about. I'd say that for every small game I play and enjoy, I play ten highly ambitious, complex and feature rich games. I will always be more motivated making a game that I would want to play myself. Being part of the audience is absolutely fundamental to Nine Dots' culture.

Tanya: Hah! Well, maybe that matters the most after all, because I’m definitely the exact opposite. I play ten smaller indie games for every one sprawling AAA title, and of course I also want to make games I’d want to play myself. Moon Hunters is my ideal game that I wish already existed so I didn’t have to make it. In a way, maybe we're both just trying to justify what we want to do anyway, which is make whatever game we want to play and make money out of it.

Guillaume: Amen to that!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like