Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"If I focus on game design, I may be able to make a fun game, but I won't have the analytics, the strategy, or the structure to make a game that will sell."

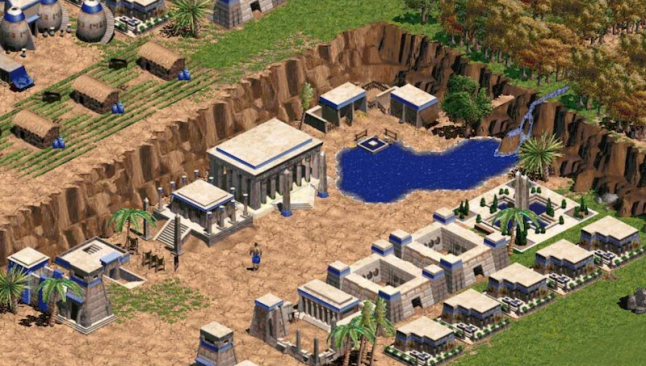

Bill Jackson, chief creative officer at Boss Fight, has been around the block. From Age of Empires, to Halo Wars, to Boss Fight's new game Dungeon Boss, Jackson has always been a designer of tactical player experiences.

But at Nasscom GDC in Hyderabad India, he says the old days of siloed designers and product managers is over. "No matter what the market says, don't lose sight of the fact that you're making art, you're making entertainment," explains Jackson. "You have to have a process first that can help you make that, before you work on anything else."

In many companies, it's common to pair a game designer with a product manager and let them fight for control of the game -- especially in free-to-play development.

Jackson believes your best chance of success lies somewhere between the two parties. "If I focus on game design, I may be able to make a fun game, but I won't have the analytics, the strategy, or the structure to make a game that will sell," he tells me.

"In free-to-play, you can't graft that stuff on later. But if I go the other way, and say I want to create a game with this feature list, on this platform, and I want to market it this way, without that design soul you're unlikely to have something anyone will want to play. So we try to unify the role into what we call product design."

"I think we talk about game design too much," continues Jackson. "We should talk about products, which these are. Product design is a holistic approach to building a product."

There were hints of this in Age of Empires, which he worked on as a designer 16 years ago."We had a story about a user; who would that player be, and how would they interact with the game?" he says. "People could say it was successful because it was so fun, and it had a bright world. Or was it successful because it could run on the lowest end laptop you could run at the time?

"The truth is, it's both. Without that ability to run on the lowest end laptops you could buy, I do not believe it would have been as successful as it was."

Jackson learned to think about product design from cliffhangers in Star Trek -- specifically episodes where the Enterprise would blow up before every commercial -- and the crew had to get out of a time loop within the length between those commercials.

Essentially, cliffhangers support the business model of commercials, discouraging people from switching to a new channel. So a cliffhanger like this becomes a marriage of art, platform, and business model.

"We say I'm putting it on this platform or that platform all the time, but there's more to the platform than just what the device is," he adds. "It's combined with the market forces into a single thing that you need to consider. What's the business model? What are the controls? What are the logistics of getting software?

"You have to think about download size, and expectations. What does the user think software should work like on this platform? What's the competition? Platforms change over time. And then there's marketing. How will I let people know that this exists?

"And what about usage patterns, which are not the same across most platforms. In VR, you might stay there for hours, but on a smartphone, you might interact with it several times per day for five minutes at a time."

Jackson discussed the arcade model, prominent in the '80s and '90s, as a prime example of product design. After all, arcades had marketing (attract modes), they had data (number of quarters used), and platform variance.

One of the issues though, was making sure people couldn't play forever on one controller. You could make a game difficult, which works, but it also shuts some people out.

You could have an endgame, where you can only play through two loops of the game, as the Ghosts 'N Goblins series did, but Jackson says this is inelegant.

"The best way, I think, is competition. In Street Fighter, when you lose, it was to a human, not the game, so it feels fair. This is a perfect assessment of the platform and its intended software from a design, user, and monetization standpoint," he continues.

"This fights a bit against the idea of pure artistic expression, but that's never really been true. Even Michelangelo's David had to work against constraints. Maybe it had to be designed to be outside. Maybe there was somebody's nephew it should look a bit like.

"It was paid for, and designed accordingly. You have to marry that idea of pure expression against realistic constraints, and that's what I mean by product design."

You May Also Like