Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

It's a common concern that the game industry's strong focus on creating sequels is an obstacle to innovation. But does the expectation of sequels stifle the potential for interactivity in narratives?

(Originally posted at my website at http://www.chardish.com/.)

One of the most common lamentations of the gaming public is the perceived lack of innovation in the mainstream gaming industry. The trend of "sequelitis" - whereby game developers repeatedly milk more games out of the same franchise, rather than developing new worlds and characters, is considered to be an obstacle to innovation in the world of game design.

The prevalence of sequelitis in the industry is evident in the parlance of the business. We have a special term for an original game in an original universe: "new IP," as if it's a given that a successful game will become a franchise that spawns sequels. And why wouldn't it? The most successful games in the industry are sequels, and every business-minded developer dreams of striking gold on a series with the cash-generating power of Call of Duty, Halo, The Sims, or Warcraft.

The problem with this phenomenon is that it stifles innovation not just in game mechanics, but in narrative structure.

More...

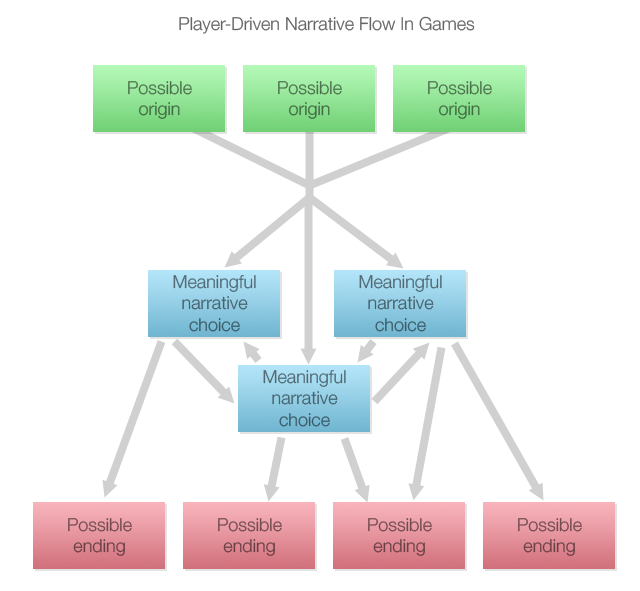

Consider the flow of a game narrative to be a series of origins and endings. An origin is a point in the narrative from which the game begins. Though most games have a single origin, a significant number (particularly Western-style RPGs) allow the player to choose between multiple origins, typically through a series of pre-game choices. An ending is a particular state in which the game ends. Not merely a non-interactive video, the ending is a representation of the entire state of the game at its termination, not merely the ending the player witnessed. (For example, irrevocable choices made along the path of the game, such as the player's decision to kill a particular NPC, found or destroy an organization, or to pursue a particular romantic interest, are encapsulated in the ending.)

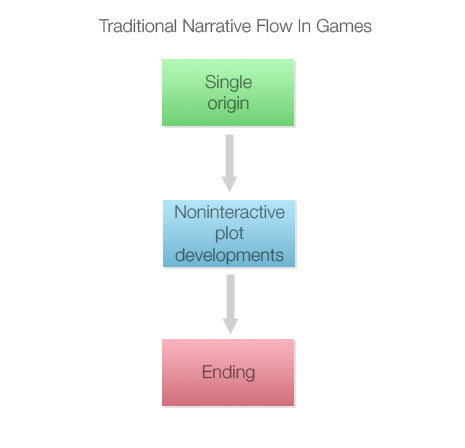

The vast majority of games have a totally non-interactive narrative. The player begins the game, plays through it, and sees the ending, with little to no influence on the outcome of the narrative. (See figure below.)

Traditional narrative flow in games

Alternatively, a game developer can create a rich set of narrative choices for the player to partake in, with the natural expectation that the player will not be able to experience the results of all these plot branches on a single playthrough. There are a rich variety of possible endings depending on the choices the player made (and, in some cases, even whether she skipped entire sections of the game or not!) (See figure below.)

Player-driven narrative flow in games

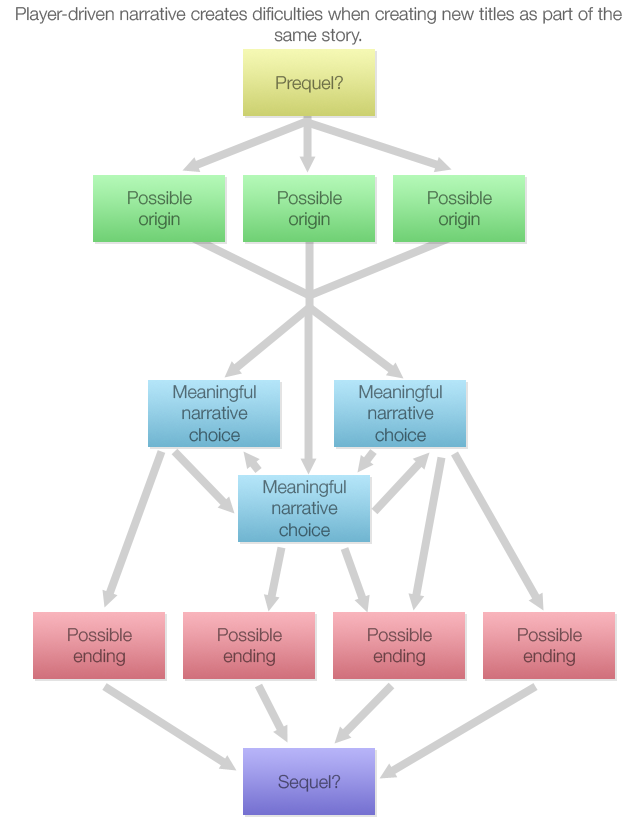

Unfortunately, when creating a sequel, in order to create a continuity of plot while still preserving the player-driven narrative, the developer is faced with a problem: the origins of the sequel have to match up identically to the endings of the previous game. (The problem is reversed in the case of a prequel.) The developer has to create a narrative in the sequel that makes sense no matter what decisions the player made. (See figure below.)

The problems presented by sequels

This presents an uncomfortable business dilemma for the developer of the sequel. He must either a) create large amounts of content that will be unexperienced by the majority of players, or b) ignore the choices made by the player in the first game. Neither of these are appealing: the former is fiscally costly (games have budgets, and content isn't free), and the latter sends a poor message to players (your choices from the first game didn't really matter.)

Several developers have made attempts to solve this issue.

One set of player choices from the original game (usually the most common one) is chosen as "canonical" and all other choices are deemed to have never happened. This is certainly the easiest solution from the perspective of the developer: it circumvents the issue entirely. This approach is very common in early real-time strategy games that allow the player to choose sides in a single war.

Downside: Ultimately, the player is not an agent in the narrative at all, and her choices are not meaningful. A sense of immersion in the narrative can also be marred by an expectation that the player's choices will be overwritten by the developer if convenient.

Sequels to the game do not take place at future points in the game's chronology, but take place concurrently with the original game.

Downside: This approach is difficult to sustain indefinitely - it gets harder and harder to create stories in the same fictional universe that exist independently of the original story. In addition, the sequel may be too loosely connected to the original, disappointing players (see Chrono Cross.)

Common in Western-style RPGs, the sequel takes place in a completely new part of the game universe. Travel to the original game's locations is severely restricted or prohibited. See: most of the old PC AD&D Gold Box games, the Fallout series, the Elder Scrolls series, presumably Dragon Age 2.

Downside: The player doesn't get to witness firsthand the long-term effects of her choices in the original game. There is little or no feeling of a continuous narrative between games.

Characters, locations, and organizations persist between the original game and the sequel, allowing a strong feeling of narrative continuity between titles. However, if a character, location, or organization's fate was decided by the player in the first game, they have almost no impact on the plot of the sequel. Mass Effect 2 is a recent example of this approach.

Downside: Feels awkward when narrative elements that were important in the first game suddenly cease being important to the narrative in the sequel.

Of course, there's a straightforward way to solve the problem altogether: simply design a game to be a complete experience without the potential for sequels, and let the player have a serious role in determining the outcome of the complete story. For all its faults, Heavy Rain is a good example of this principle at work. This is courageous and commendable.

Unfortunately, a large number of developers have simply taken the easy way out: creating non-interactive narratives so that sequels can be easily harvested. But there's so much room for growth in the craft of interactive narrative. Interactivity is unique to the art of games; it is the one element that distinguishes it from all other art forms. Yet many developers seem content to keep interactivity and narrative in separate spheres in the hopes of creating profitable business enterprises. While this may be good business, it's hardly making use of the full potential of the medium. I greatly look forward to the stories that will be created when developers have the courage to truly cast aside the potential for sequels and fully put the player in the role of co-storyteller.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like