Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the third installment of his feature series, Simon Ludgate examines the evolution of the free-to-play MMO, and how games can implement -- or how they should implement -- different monetization schemes for best economic benefit and user satisfaction.

[In the third installment of his feature series, Simon Ludgate examines the evolution of the free-to-play MMO, and how games can implement -- or how they should implement -- different monetization schemes for best economic benefit and user satisfaction. ]

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, I discussed the game mechanics of economies and how they relate to game design decisions: how to make games fun and fair by designing economies for the types of worlds that exist within MMORPGs.

In this final installment, I'm going to take a step back from the game-centric theory and look at game design from a marketing perspective, and discuss how the recent trend towards the free-to-play model for monetizing games affects game design and, in particular in-game economy design.

This is a particularly interesting topic, because many "F2P" games rely on a dual-layer economy in order to prosper: the in-game and microtransaction markets have varying degrees of intersection in different games.

The free-to-play market transition has not only been important because of its success, but also because of how it challenges deeply-rooted conventions and ideals that have existed at the core of marketing since the first goods were bartered.

That basic idea is "everyone pays." It's the basic idea that's fueled the endless war on piracy, for one thing. Pirates aren't paying! Marketing is in uproar! It's the gaming apocalypse! But does this idea even make sense with digital goods?

Video games are a type of good that economists class as "non-rivalrous." This means that, if one extra person "consumes the good" (economic-speak for "plays the game") it does not cost the producer any more (zero marginal cost of production) and it does not cost the other consumers any more (non-subtractable, meaning it doesn't stop anyone else from also using it at the same time). This means that if someone pirates a video game, it does not have any impact on either the producer or other consumers of that game. Strictly speaking, of course.

Video game publishers have long equated piracy with lost sales, which in pure economic parlance isn't true. Technically, it's a failure to sell; a marketing failure that has less to do with "stolen" product and more to do with an inability to persuade consumers to pay for a product that's otherwise available to them for free. The video game industry needs to take a lesson from the bottled water industry and worry more about branding and prestige than "lost sales". Every glass of tap water is a "lost sale" for a bottled water company, but you don't see them slamming the DCMA on municipal water systems, eh?

The games industry's thirst for payment from every single consumer has led it to conflict with consumers at large; a conflict currently being targeted for juicy profits by the new cadre of free-to-play game makers. Rather than trying to squeeze blood from stones, they set up their buckets and wait for it to rain. And when it rains, it pours! Especially when it comes to an overused analogy...

In order to understand recent trends in F2P game design, I need to take a look at how they developed. We start at the obvious point of origin: the traditional subscription-based model. A subscription works on the principle that every consumer of a good pays the same price and has the same access to some good. This can mean unlimited access, beyond what a subscriber can possibly consume.

For example, I used to subscribe to cable TV, which meant a flat monthly fee and access to 80-odd channels. I couldn't watch TV 24 hours a day for a full month, so the amount of value I got out of my subscription fee varied. Moreover, I couldn't watch all 80-odd channels at a time, so I was, strictly speaking, paying for several thousand times more TV than I actually watched.

But it was fair. Everyone paid the same fee, everyone got the same channels, everyone watched as much or as little of whatever channel they wanted. The notion of fairness is so important I dedicated the first part of this series to it. That's why I'm borrowing another major concept from my first part to explain what happens in subscriptions: the notions of time and money.

In general, the amount of time and money people have to spend on entertainment are inversely proportionate. That is to say, that the more money you have to spend on games, the less time you have to play them. That's because the things that get you money tend to take up time. The more time you spend getting money, the more money you'll have, and the less time you'll have. I don't mean this as an absolute description of all people, but this explanation holds true for this fairly large group of people.

With that in mind, here's what the subscription model looks like, across a spread of people with varying amounts of time and money available to spend on a game:

The people represented by the left group of columns have the most time and the least money; in this example, not enough money to pay the monthly subscription fee. As a result, that group of people isn't permitted to play the game.

There are two issues with this scenario: first of all, that group of people that's not permitted to play does have some money to spend, just not enough for the subscription. That bar might also represent a disproportionately large group of people, so that small bar might actually represent a very large amount of money.

One option to reach that group is to lower the fixed fee. But then you're charging less to everyone else. Historically, that was the group targeted by F2P: by making the payment options smaller than an arbitrary subscription fee, the hope was to monetize an unreached market segment. We can see how this happens with one of the early F2P payment models, which I refer to as the energy model.

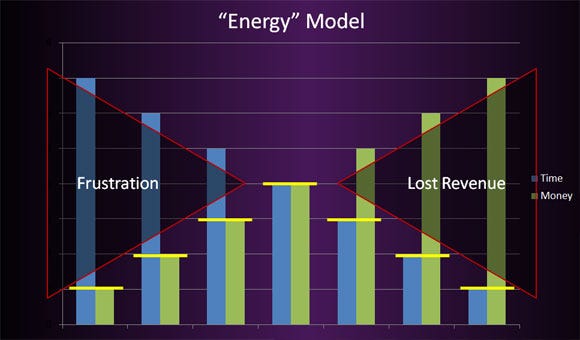

The energy model operates on the premise that players can play for free for a little bit, then have to pay a little bit to play a little bit more. The more you want to play, the more you have to pay. Games that use the energy model usually tie some core activity in the game, such as fighting monsters or going to a dungeon, to an energy bar which slowly refills each day or week. If players want to play after the energy bar has depleted, they can do so by buying more energy from the item shop.

There are two big problems with the energy model. For the players with lots of time and not much money, they quickly run out of energy and can't afford to buy more; this leads to a great deal of frustration because they have all this time they want to spend playing games and the game says "too bad."

However, there's also a big problem on the other side of the graph: lost revenue from the wealthier players. These people don't have much time to play anyways, so they don't run out of energy and don't feel the need to buy more. All that money they're willing to spend goes unspent.

There's a third problem that affects both subscription and energy-based games. That's because of a funny thing about time. Unlike money -- which you spend because you have to, but you're just as happy not spending it if you don't -- time is something that you actually want to spend. Thus the frustration in the energy model: unspent money isn't frustrating, but unspent time is.

However, there's a flip side to this: some games have minimum time requirements, just like minimum money requirements.

When Rift was released recently, I was all excited to play it with my friends. Most of them didn't play WoW with me because they didn't have the money to spend on the subscription fee. But now they're all working and money's not a problem, so I asked them if they were going to get Rift. They all said no. Again! Why? Now they said they didn't have the time to play it. Games like WoW and Rift, they said, were too time-consuming. The idea of "time cost" introduces another big problem in MMO design:

Just like the money requirement kept users out of the subscription model, the time requirement of these kinds of games often does the same to the opposite end of the spectrum. And, arguably, games like WoW with their "four raids a week, four hours a raid" requirements hit much harder than the measly 15 dollars a month.

This is something that the energy model, which needs players to keep on playing in order to make money, misses out on: it's conflicting goals of getting people to pay to play, and forcing people to play enough to make playing worthwhile, which trims off the edge users just as much as subscriptions do... or possibly even more so.

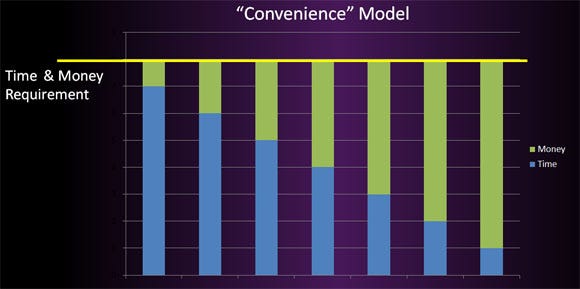

The current thrust in the F2P "revolution" aims to remedy both these inefficiencies. It's what I call the "Convenience" model. This model is based on the very model I've been describing here, that money and time are scarce resources, and people tend to have one or the other. In the convenience model, you can play to progress, pay to progress, or any mix in between.

From a purely marketing standpoint, it's genius. People can spend all the time they want, and all the money they want. There's no missed opportunity to monetize people here. However, from a game design perspective, it's a catastrophe.

In order to make the convenience model work, games have to be designed with a very high barrier to get that "worthwhile" experience from the game. The requirement in time/money has to be very high in order to get the most money out of everyone. If that bar slips too low, people stop paying what you expected to get. If that bar slips too high, people stop playing, period, because they don't have any fun even after spending all the time and money they have available.

The convenience model tells game designers: design a game that is as inconvenient as possible so that we can sell convenience to players. Actually, make a game that is horrendously addictive so people have to play it, but make it as unpleasant as possible so people are willing to pay money to avoid having to actually play the game. Most game designers I know didn't get into this industry to make games that people loathe so much they pay real money to not have to play it.

Plus, gamers are on to it. They're getting savvy. They're starting to realize they're just being taken advantage of and abused by these sorts of addictive games. Gamers don't want to be a blue/green bar on some economist's spreadsheet. They want to be playing games. They want to be having fun.

The successful F2P games of the future are going to be successful in the same way the bottled water industry is successful: they're going to operate on the principle of giving opportunities to people who want to spend money rather than trying to corner people into the position where they have to spend money.

What all three models I've described above have in common is that they're all based on extracting revenue on a user-by-user basis. All three look at each user and ask: "how are we going to get this user to spend money?" Most importantly, they all ask how users will spend money for themselves. In the subscription model, each user pays for their own access to the game. In the energy model, each user pays for their own play time. In the convenience model, each user pays for their own convenience.

This is all well and fine when you're selling a single-player game. But all of these games are based on the premise of being multiplayer. They're billed as massively multiplayer.

When the premise is playing with other people, why let your marketing schemes get in the way of people actually playing together? Is there anything worse than having a friend stop paying their subscription, or run out of energy, or fall behind in levels?

Recently, game companies have been taking note of the importance of social relations in player retention. No matter what your model, player retention is important, if only because players are what are paying you for your game.

But even more important is that a multiplayer game needs multiple players to be fun. When too many players quit, the rest consider quitting too. That's why server mergers have become a big ticket issue in trying to stretch out some extra life from MMORPGs that are running out of players.

Imagine that you were running a successful MMORPG, and in your MMORPG there was a guild of 30 people, but the guild master and one other "social glue" player canceled their subscriptions. The worst case scenario is that the guild completely falls apart and the other 28 players cancel their subs too. But, if you gave free subscriptions to the GM and that key other player, they keep playing and the other 28 keep paying. Win?

Not really. First of all, good luck identifying the social glue players in a player base of 10 million. They might not even be the obvious choices like guild leaders, officers, big forum posters, or people with lots of other people on their friends list. They might just be those quiet people in the background who get things done when no one's looking. Pigeon leaders, as my high school physics teacher would say.

[One day, in robotics club, our teacher told us a story about leadership. Imagine someone walks into a park with a bag of breadcrumbs, sits down on a bench, waits a bit for pigeons to show up, then quietly sprinkles the breadcrumbs around. All the pigeons flock to him. Now imagine someone else marches into the park, sees the flock of pigeons, and starts throwing fistfuls of crumbs at them yelling "EAT THIS!" Who do you think is the pigeon leader?]

Another problem with giving the two key people free subscriptions is that it isn't fair. The other 28 would probably demand free subs too. One of the problems with the "fairness" of the subscription model is that it is so fair that it's hard to circumvent that "fairness" even if it would be desirable to do so.

But there's an important lesson to learn here: people often play multiplayer games in order to play them with other people. If your multiplayer game has any barrier of entry, it could end up having collateral damage on these friends of potential players.

Here's another story. I have a League of Legends account, but I almost never (once or twice a month) play on my own. I don't really like the game that much. But I have friends who really like it, and these friends often ask me to play and even though I'm not terribly keen on the game itself, I am pretty keen on playing with my friends, whatever the game. So when they message me with "LoL?" I usually say yes.

League of Legends

League of Legends is interesting because it isn't based on the subscription, energy, or convenience models. In LoL, you don't need to pay a subscription, you don't need to pay in order to play the game, and while there are, technically, convenience items in the Riot store, they're hardly relevant to the gameplay experience.

Actually, convenience might be relevant in LoL because you can also unlock champions with Riot points, but since the free point system, IP, is sufficiently common to even casual players and the 10 free champions each week usually offer plenty of interesting variety, I don't find the game sufficiently "inconvenient" to categorize it as a convenience-model game.

Although Riot refuses to comment on its customers' shopping habits, I suspect that the way LoL primarily makes its money is through the sale of champion skins. Skins are purely aesthetic. Cosmetic. Bonuses. You never ever need to get a skin to play or enjoy or get the most out of the game. But lots of players do like skins -- including the friends I play LoL with. They play with skins, I don't, but that doesn't matter; we can all play together and enjoy the game together, no barriers to entry.

Then, this Christmas, one of those friends got me a LoL gift card.

Maybe it was a bit of a gag gift. We all got a laugh out of it, because I was so staunchly opposed to "wasting money" on skins, but I cashed it and, so far, have bought one single skin for my favorite champion. Go figure.

But here's the real point of the story: Riot sold that gift card because it allowed a player to play for free. More importantly, Riot allowed that player to play for free even though that player refused to ever buy anything from them, and that player would have left the moment the game became unfair for non-paying players. The company made that sale because it was happy to let a freeloader stick around.

Understanding social networks isn't just important for player retention: I argue that social networks will be the core basis for the future of F2P games. The mentality driving games will shift dramatically from "how can we get each player to pay something?" to "what opportunities can we give players to spend more money?" As Craig Morrison, creative director for Age of Conan at Funcom, said to me, "it's not about making players have to pay, it's about making them want to pay."

But even with the shift to "want" to play, most games still deploy with a user-centric model. Most shops force players to buy their own "item currencies" (such as Riot points) and then lock those currencies to the account. Everything bought with those currencies is also locked to that account. Look again at Riot's model: my friend could buy me a gift card, but they couldn't just give me Riot points and they couldn't have bought me skins.

The problem with the Riot model is that gift-giving is linked to a physical item: a game card. In theory, a user could buy extra game cards, scratch off codes, then email over codes to friends, but how many people are going to have a stack of game cards on hand for impulse gift-giving? And how many people are going to give game card codes away to strangers they meet online? Not many.

What MMORPGs like WoW have shown us is how powerful and strong relationships with complete strangers can be. Complete strangers meet up, form guilds, raid for years, all without ever knowing each other's real name.

The gift-giving among these friendships can become very strong: my guild in WoW had a guild bank stocked with a wealth of valuables that everyone was welcome to take, but stayed stocked up on the generosity of the majority of guild members.

Imagine how many more Riot points Riot could sell if players could meet a friend in a match and, right then and there, gift them a champion or skin? Even better, Riot could capitalize on the spur-of-the-moment nature of gifting and allow players to gift champion unlocks or skins during the matchmaking that takes place prior to a game. Maybe outright unlocks as gifts might be too much for that sort of spur-of-the-moment scenario, but a temporary one-match unlock for a few RP would add up to huge extra sales.

There is one further step games can take, something I haven't really seen implemented quite so thoroughly until I downloaded Perfect World International's Forsaken World when it was added to Steam's F2P lineup. Giving gifts to in-game friends is a good step, but FW goes a step further by integrating the item shop with the game's in-game economy.

Linking a game's item shop and in-game economy is the ultimate culmination of everything I've talked about since I began this series. In Part 1, I talked about the fairness of spending money instead of spending time playing, and that's been better examined here in the various time vs money F2P models.

In Part 2, I talked about giving players better control over the pace of currency creation through various means, and linking all of a game's currencies through internal markets gives players that full control. And, most importantly, it completely divests the people who spend money in the item shop from those that consume the goods from the item shop.

The most notable result of allowing players to trade -- in-game -- items bought with real money is that people can make purchases on behalf of others without having to gift them those items. In this scenario, a player needn't even know any other player, yet can still want to buy something for someone else because they'll sell it on the open market.

Games that focus on user-by-user sales are limiting themselves because they don't embrace freeloaders and they don't embrace whales. And it's the whales that F2P games should be hunting. The term "whale" differs a bit depending on how it's being used -- for some, a "whale" is merely someone who spends more than most -- but the real crux of the "whale" concept is someone who spends more than they would if the game restricted them to self-only purchases.

That's why games like League of Legends will never have true "whales." Once you've unlocked all the champions and skins, you cannot spend any more money on LoL. Games with self-only limited item shops have a limit to potential sales: sell everything once. If you can't buy more and give it away, you can't spend more money. That's why storefronts like Steam, with their ability to buy bundles and gift away extra copies, work a lot better than storefronts such as Turbine's for Dungeons & Dragons Online and Lord of the Rings Online, where everything is bound to the purchaser's account.

Just allowing players to give gifts is a good start, but linking item shop and in-game economy takes that a step further. Whales are only as valuable to you as their ability to trade away the extra stuff they bought from your item store. If whales can only trade with real life friends, they might only give to one or two others (like with LoL game cards). If they can trade with in-game friends, that reach extends to 20 or 30 or, for particularly charismatic whales, hundreds of other Steam users.

The ultimate whale would be someone able to give stuff to complete and total strangers -- or, rather, trade stuff to them. This is where EVE Online's PLEX or Forsaken World's Eyrda store really shine: the items or currencies bought with real money can be placed on the in-game marketplace, meaning that every player can look on the market and, if they have enough game currency, buy them. Suddenly, the social reach of a single whale is the entire game.

This integration of real-world and in-game economies is what I suspect will lead the next generation of free-to-play titles. Games developed, from the ground up, with F2P in mind, rather than the "freemium" conversions, which are more like parceled-up free trials, which have become all the rage these days. These will be games that take a good hard look at that "time vs. money" graph and say "we aren't going to try and extract either from our users. We're going to let them spend what they want."

I, for one, am really looking forward to "F2P: The Next Generation".

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like