Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

You can't have fun without inaccessibility. It's an iron law of play. That has implications for game design and accessibility advocacy, and it's the subject of this post.

This is a modified version of a post first published on Meeple Like Us.

You can read more of my writing over at the Meeple Like Us blog, or the Textual Intercourse blog over at Epitaph Online. You can some information about my research interests over at my personal homepage.

---

There’s an awkward secret at the heart of the quest for game accessibility. Well, I guess it’s not a secret so much as an uncomfortable truth that we don’t talk about a lot. It’s pretty much unique to this field of accessibility work – there are no real parallels in other spheres of human experience. Accessibility in gaming is different because games are different. The quest for game accessibility is one of frustrations because the quest itself is fundamentally against that against which makes games worth playing in the first place. This is true of board games as it is true of video games, but my focus here will be video games since that’s where the best lessons can currently be drawn.

The awkward secret is that inaccessibility is where fun comes from.

Currently in games discourse there are two largely independent ways that people describe accessibility. The first is the correct way, the way in which we on the site describe it – the removing of barriers to interaction so that those with permanent, temporary or situational impairments are able to play as easily as possible. The other (wrong) definition tends to be focused on mastery of the play experience – the ramp that leads from new players becoming skilled players in any individual game. When people in the latter camp talk about accessibility it is in relation to things like difficulty modes, ‘mastery through persistence’ and the essential learnability of rulesets.

Let’s call these two camps ‘accessibility’ versus ‘learnabillity’.

The clash of these two perspectives has led to some of the most frustrating examples of two well-meaning groups spending most of their time talking past each other.

On one hand are accessibility advocates who correctly point out that things like difficulty modes are incredibly valuable accessibility tools – they can remove challenges that disability and impairment make intensely difficult to overcome. They argue that ‘difficulty’ comes in a lot of different forms and flavours, not all of them obvious. They note that ‘easy mode’ doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone and that the provision of such a mode doesn’t need to impact on those that seek a greater challenge.

On the other hand are those that, equally reasonably, point out that much of the challenge of games like Celeste, Dark Souls and others is bound up in a context of necessary difficulty. They say, and not without merit, that to alter the delicate balance in games of this nature is to undermine the game itself. It would be technically easy to implement a less challenging mode of play, but you’d never be able to capture the essence of what the game was supposed to be.

The problem is that both groups are right, but for reasons that make it feel like the other is wrong. I don’t believe you could force an ‘easy mode’ into Dark Souls without changing the nature and texture of the experience. I think designer intent is something that should be honoured, even if its presence in a game is one that only manifests erratically. At its heart every game is already a compromise between vision, logistics, skill, tools, timescale and budget. Few designers though truly intend for their games to be indiscriminately inaccessible.

I think in the end here this disconnect is a side-effect of the awkward secret at the heart of this work. The fun in games is almost always bound up in overcoming the inaccessibilities that have been designed into the fabric of its experience.

Consider the game football. I don’t really know anything about football so I don’t know why it’s my go-to example. But imagine the game of football was one player kicking a small ball into a large goal from a few inches away, It’s hard to imagine that would be the basis for the international juggernaut of tribal affection that characterises the modern game. It’s just not interesting. It’s just not fun.

So instead, we take that goal and shrink it. We take that ball and increase its size. We make you kick the ball from farther away. We add inaccessibilities. We add them carefully and with thought, but we intentionally make the game more difficult.

The goal in any game isn’t to accomplish a simple task as easily as possible. It’s to accomplish a set task in a way that is obscure and awkward, but not so obscure and awkward that it’s unpleasant. Game design is all about balance, but not in the sense people often say. It’s the balance between ‘the things we need to do’ and ‘the things stopping us doing them’. In other words, game design is the act of intentionally implementing inaccessibilities. Every barrier put in place between a goal and a player is an accessibility obstacle that by definition did not have to be there. It was put there by a game designer.

Our modified game of kick-the-ball still isn’t fun. It still isn’t interesting. So we move the goal much farther away. We add another goal that we must defend while attempting to strike the other. We add in a goal-keeper. Then we add in defenders. Then we add in team-mates to help us deal with the defenders. We add constraints around the pitch. Time limits. Penalties. Free kicks. Corners. Every single one of these things reduces the accessibility of the game while simultaneously making it more fun. The link between the two is absolute. To increase fun is to increase inaccessibility in some fashion. You can’t escape this – it’s a fundamental law of play.

Oh dear.

For another example, allow me to let the late, great Robbin Williams discuss the origins of Golf. Warning, this is not safe for work.

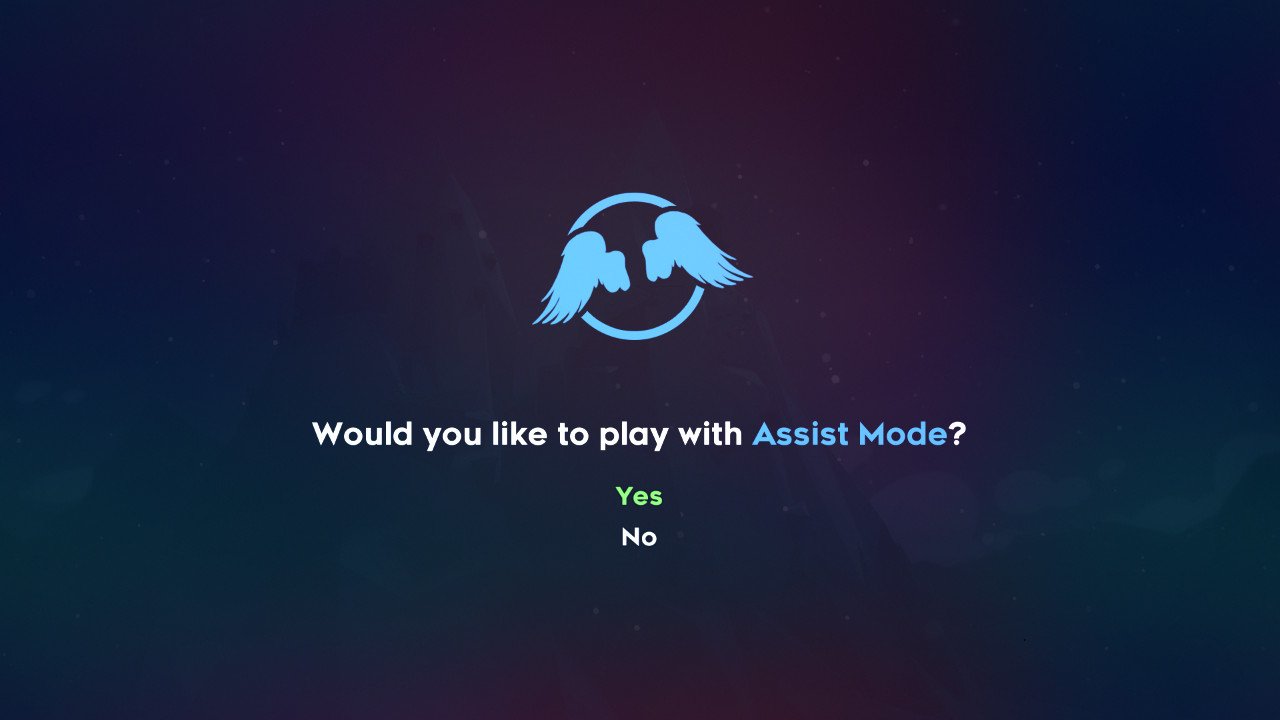

People aren’t wrong when they say that to change the difficulty of a game is to change the fun. I have been playing a lot of Celeste in the past few weeks and I have been tempted many times by the excellent assist mode it offers for accessibility support. For those that have never played Celeste it is a tough, punishing puzzle-platformer where precise movement and timing are constantly required and a death counter is your regular companion. It also comes with an amazing set of options that let players fine-tune the experience so it matches their own capabilities. It’s really good.

I resisted using that assist mode because I was determined to master the game as it was presented to me. I’m lucky enough that that’s a choice I have. For some people the choice is between assist mode and not being able to play at all. I think that Celeste is diminished as an experience if people rely on assist mode when they don’t strictly speaking need it, and when people rail against ‘easy mode’ they are often expressing a similar point. You cheated note the only the game, but yourself. Celeste is built on a series of small, intimate little game loops. Death happens consistently but as time goes by you build up a remarkable sense of fluidity because all that failure is dumping vast amounts of wisdom into your muscle memory. The link between difficulty and mastery is beautifully precise. Never have I enjoyed the experience of frustration quite so much.

This then is the learnability school of accessibility discussion. It acknowledges that some games are simply designed to be built around a call and response of challenge and mastery. Dark Souls with an easy mode just wouldn’t be Dark Souls. Magic Maze without enforced silence wouldn’t be Magic Maze. I don’t know what Scrabblewould be without letters and mastery of word placement but it certainly wouldn’t be Scrabble. The balance of inaccessibility versus skill is drawn from a particular philosophy and that cannot be easily undermined. As such, to implement ‘accessibility’ in such a game is to break it for everyone because fun is intricately bound up in its negation.

The problem with that argument though is that it depends on a fairly one-dimensional understanding of how the two elements relate. Fun is inaccessibility, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that inaccessibility is fun. What’s important here is that inaccessibility should be intentional. Not all inaccessibility is necessary for a game to be fun. The inaccessibilities that must be retained are the ones that are required to create the game experience. Everything else is optional or an oversight, and it’s these areas to which we should be directing our efforts.

Our view for the site has been consistent – we’re not believers that every game can be accessible to everyone. We’ve also said on occasion that we’re not convinced every game should be accessible to everyone. The nature of the relationship between creativity, game design and accessibility is complex. To insist every game should be playable for everyone is to put a massive constraint on innovation. Only a handful of games we’ve looked at on Meeple Like Us could be argued to be substantively accessible to everyone and if that were the barrier we expected games to clear it would be unreasonable. I understand that argument can seem cold and calculating because the inevitable conclusion is ‘Some games just aren’t for some people’, but this site is pragmatic at its heart. Perfect, as we have often remarked, is the enemy of the good. The end-goal for which we are aiming is that everyone has lots of great games they can play with the people in their lives. To do that, we argue that if a game doesn’t need an inaccessibility it shouldn’t have it. If we ever we the stage where that modest guidance is routinely followed we can start worrying about whether everyone can play every great game. We aim for a good, achievable goal rather than an unachievable ideal goal.

If game design then is substantively the act of intentionally engineering inaccessibility, it is beholden on good designers to ensure that all their inaccessibilities genuinely are intentional. Where there are inaccessibilities that do not contribute to the fun, it’s time to engineer them out of the experience. Good design maps inaccessibility to difficulty in an elegant way. Great design leaves no inaccessibility that didn’t need to be there.

This is a big part of the story but it’s not the whole story. If the act of meaning is a collaboration between creator and viewer, the act of playing is a collaboration between game and player, The problem that people often overlook in this discussion is that you don’t just get the inaccessibilities you design. The inaccessibility in a game experience is the sum of those in the game plus the impairments of a player. It’s all fine and well to say ‘This is a game where you master through persistence’. The contours of mastery change from person to person. Greatdesign leaves no inaccessibility that didn’t need to be there. There’s a level above even that, Empathic design understands that that difficulty is not an integer value in a spreadsheet. It’s a complex function that changes depending on external factors. Empathic design is wise enough to understand that assumptions of difficulty need to come with error bars and that the designer is not well placed to know their ranges.

http://pgfplots.net/tikz/examples/graph-in-table/

In this respect I tend to prefer fine-grained accessibility settings over the broad-tool of difficulty levels when it comes to finely balanced games. They are ways to give the player ownership over the decision of what challenges they can reasonably be expected to meet. The assist mode in Celeste as an example permits the game to be slowed down, for air-dashes to be more generously provisioned, and for stamina to be an inexhaustible resource. They’re cheat codes in spirit, but not in implementation. None of them need detract from Celeste as a meaningfully challenging puzzle platformer. Instead, they let players build forgiveness into the learning curve. Celeste is pixel-perfect and uncompromising in its design and what assist modes do is apply some flex so players bend rather than break.

What this does in turn is create a consent-based model of difficulty where players can find the sweet-spot between their own capabilities and the challenges of the game. Importantly, they come with zero cost to the game itself. Nobody has to use the assist mode if they don’t want to use it. Nobody’s game is negatively impacted by someone else using them. Those that would deny play to others on the basis of their own lack of self-control should reflect on what this behaviour says about them. It is not a good look.

Those that argue against assist and easy modes on principles of purity of design are doing so from a flawed understanding of intentional inaccessibility. They forget that sometimes accessibility challenges in the real world can cause inaccessibility challenges in a game to spike dramatically upwards. Designers can’t meaningfully design around this. They can’t design games for skill levels that change and modulate on a daily, hourly, or even minute basis. All they can do is give the right tools to those that are best placed to make that determination for themselves.

Inaccessibility then is a choice, but so too is the decision to deny reasonable accessibility compensations to those that require them. It is very heartening to see how much this lesson is increasingly being taken to heart by the video game industry. The tabletop industry could learn a lot from their example.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like