Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

University Sorbonne Nouvelle senior lecturer and author Alexis Blanchet breaks down the statistics of video game film adaptations, analyzing what films get turned into games and why -- over the course of the entire game industry from 1979 to 2010.

April 5, 2012

Author: by Alexis Blanchet

[In a report originally published on the INA Global website, University Sorbonne Nouvelle senior lecturer and author Alexis Blanchet breaks down the statistics of video game film adaptations, analyzing what films get turned into games and why -- over the course of the entire game industry from 1979 to 2010.]

Among the many links connecting the cinema industry with the video games industry, the adaptation process comes to mind immediately. This is also the most prolific, both from video game to film and vice versa, although there is some bias in the process: while the six Star Wars films gave rise to more than 120 video game titles, the most widely-used video game series in the cinema, Resident Evil, has so far only given rise to four films shot in live action, and one in CGI.

The number of films re-worked as video games is consequently much greater than the number of adaptations of video games for the cinema: several thousand game titles on the one hand, compared with only 60 or so feature films on the other.

In order to get a better feel for the true scale of the adaptation process, we have been working since 2005 on setting up a database listing all films that have been re-worked as video games.

This annually-updated count has made it possible to quantify the films involved in the adaptation process and provide proper insight into the considerable quantity of items that can be produced by two entertainment industries contributing to what is known as mass culture.

The adaptation business reveals a degree of regularity in duration and a definite profusion in the quantity of items involved: from 1975 to 2010, 547 films shown in movie theaters gave rise to around 2,000 games.

The practice of adaptation has grown over the last 35 years to become a major category in video game production today, accounting for nearly 10 percent of the total number of video games published.

The figures we have collected and analyzed come from a systematic study of about 15,000 video game titles published from 1975 to 2010 on more than 40 game platforms selected for their popularity in Western and Japanese markets.

In deciding on the platforms, we used focused on equipment that is specifically dedicated to games, or that is available in practice for playing games, like microcomputers. We did not use browser games. These are freely accessible, often based on a very simplistic game pattern, and are brought out to accompany the release of a film, only briefly available while the films are showing. Our intention in setting up this corpus was to stick to the commercial video games, the items appearing on retail websites.

The case of mobile telephones is more problematic. At the time we began this census-taking exercise, telephones were only just starting to be used as a game platform. The success of the Apple iPhone and the downloading of video games onto smartphones since 2007 should mean that we reconsider such platforms. However, the proliferation of titles developed on mobile telephones, their speed of circulation and the way they operate, make identifying and quantifying them very complicated.

Nonetheless, an overview of the few films adapted for mobile phone use confirms that they are primarily carried on platforms dedicated to video games: the mobile phone is consequently a platform ancillary to the game consoles in the very broad market coverage strategy used by the publishers.

On the other hand, by ruling out mobile telephony, we wipe out an entire continent of filmmakers, the Indian producers. Since the middle of the 2000s, the number of adaptations of Bollywood films for the mobile telephone has been constantly on the rise: from a count of three in 2005 to 60 just three years later, the meeting between a popular cinema industry, which has for years been trying to rejuvenate its audience, and the video game, which in India has been developing exponentially, has proved particularly fruitful.

We shall define "adaptation" as follows: the adaptation of films into video games is an editorial and commercial process organized on a coordinated basis between the rights-holder of a film or series of films shown in movie theaters and a video games publisher. The adaptations display the film source the varying degrees, which is used as a significant commercial argument.

To categorize a video game as a film adaptation means seeking out the clues that suggest that a game is directly connected to a film source. We thus sought to examine the eponymous features when a film passes on its title to its adaptation, the copyright and legal details shown on the packaging, notices and title screens which confirm obvious and/or claimed derivations (e.g. characters, settings, images, original soundtracks) from a film for use in a game.

About 15 significant indicators were used for each entry to set up the database, so as to determine the types of relationships, sometimes quite complex, between films and video games, and highlight the trends involved in the process of producing a video game. This mechanism, which we are continuing to develop, allows us to identify editorial strategies and investigate the traceability of items entered into the base by determining with varying degrees of difficulty the origin, linkages, lineage and so on.

Developing and publishing a video game adaptation of a film is part of the operating approach for derivative products established by Hollywood since 1970. This practice means cashing in on the heavy promotional budgets allocated to promoting entertainment films and exploiting the popularity of a saga like James Bond or Star Wars; this editorial choice strongly dictated by commercial pressures ensures a degree of visibility for the games displayed at sales outlets.

This strategy applies particularly to what is known in Hollywood as the movie tie-in game, that is, the game adapted from a film of the same name and marketed simultaneously with the release of the film in movie theaters. This simultaneous timing is a direct outcome of Hollywood's merchandising policies and multimedia development, which turns films into a loss leader for profits to be made on the production of other items. As a result, more than 90 percent of films adapted, the vast majority from Hollywood, give rise to adaptations simultaneously.

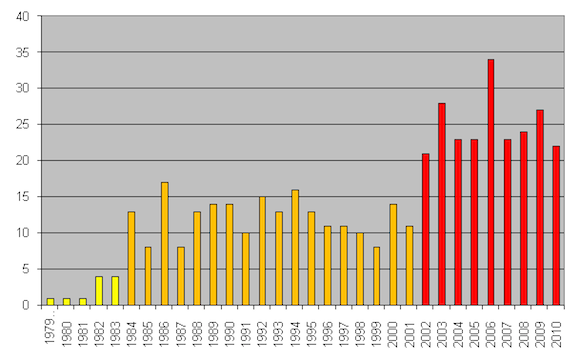

Number of films adapted simultaneously as video games per year (1979-2010)

The first arcade video game inspired by a film dates to 1975: at the end of the summer of that year, surfing on the phenomenal success of Jaws in the movie theaters since the month of June, Atari put out the arcade machine Shark Jaws. Nolan Bushnell, the founder of Atari, is said to have tried to legally acquire the operating rights of the film from Universal but was refused. Starting in 1979 with the adaptation of the Star Trek movie by Robert Wise, every year, there was at least one film adapted as a video game.

The term "simultaneous" is used when less than 18 months separates the release of a film and its appearance as a video game: during this period, simultaneous adaptation benefits fully from the only-in-theaters status of the film. Since the 1990s, and more particularly, the release of Jurassic Park in 1993, the time lapse between the release of the film and the release of its adaptation has shortened considerably, to the point where market availability has been reversed: today, the marketing of the adaptation precedes the release of the film.

Analyzing the number of simultaneous adaptations published per year brings out three distinct phases of activity: from 1975 to 1983, between one and four films per year gave rise to a simultaneous adaptation; from 1984 to 2001, the publication of simultaneous adaptations concerned on average a dozen films per year; and finally, since 2002, the average has exceeded 22 films per year.

This continuous increase in the use of simultaneous adaptations bears out the interest of film producers in this type of commercial and creative synergy with video games and their commitment to it. A few production peaks -- in 1984, 1994 and 2006 -- also reveal a lack of responsiveness of the film sector compared with the video game business.

Whereas in 1984, the video game business was deeply affected by its first crisis of any size, the number of films simultaneously adapted as games was increased by a factor of three with respect to previous years, and many adaptations were turned out by video game publishing subsidiaries of the Hollywood majors (Fox Video Games Inc. and Atari Warner).

In 1994 and 2006, two years corresponding to cyclical crises in the sector due both to the arrival of new hardware and consumer expectations, the number of films adapted also exploded. The peak in 2006 corresponded to a significant increase in the number of films released that year: 601 films, compared with less than 490 on average over the last seven years.

While we are witnessing an increase in the number of films adapted per year, it can also be seen that proportionally speaking, there is stagnation in editorial offering of this type of video game: from the early 1980s to the 2000s, adaptations represent a constant 10 percent of the editorial offering of a game platform.

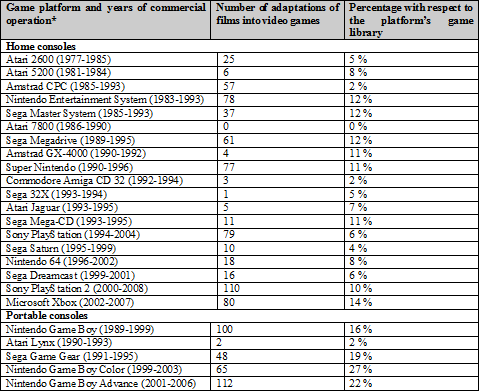

Comparison of the number of adaptations to the total number of titles published on platforms (We indicate in brackets the period during which the count was made.)

The adaptations flourish on the most popular platforms on the Western market (in chronological order: Atari, Amstrad CPC, HES, Sega Master System, Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, PlayStation).

They are, however, totally absent on the platforms destined exclusively for the Japanese market, e.g. WonderSwan or Neo Geo Pocket, which in some cases have not been officially distributed in the West. Lastly, the portable consoles, often much appreciated by children, are the platforms most widely open to adaptations: film adaptations accordingly represent from 16 percent to 27 percent of the game libraries for Game Boy, Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance.

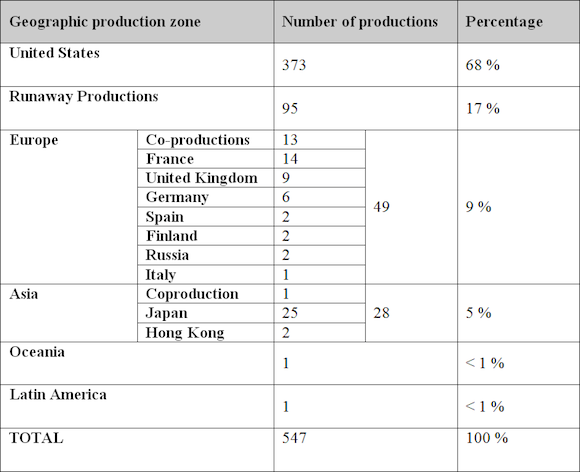

The breakdown by country of film productions having given rise to one or more video game adaptations since the end of the 1970s shows an overwhelming majority of Hollywood productions: out of 547 films, 373 are American and 95 co-productions shot in English with mostly American capital (known as runaway productions).

Europe stands out as the second largest production area for adapted films: the most prolific film industries on the continent are represented by France, the United Kingdom and Germany; a dozen European co-productions involve these countries together with the Benelux and the Latin countries. Lastly, Asia is represented by Japanese productions.

Breakdown of adapted films in terms of production zone and country of origin

Nearly nine out of 10 films adapted as video games are Hollywood productions, which goes to show that the adaptation of films into games is an American practice.

This is borne out by the fact that the vast majority of adapted video games originate, as we have seen, with American and European studios and are put out by Western publishers (Electronic Arts, Activision, Ocean, Fox Interactive, Disney Interactive, etc.) or the Western subsidiaries of Japanese publishers (Sega, Capcorn, Konami, etc.).

The films that are adapted into video games mainly belong to the major film productions of their country of origin, either in terms of their budget or in terms of their success at the box-office.

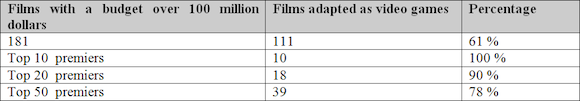

Among the 181 international productions released between 1991 and 2010 with a budget estimated at more than 100 million dollars -- which is to be considered as a symbolic line that was first reached by Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991) -- 111 have been the subject of one or more adaptations into video games, i.e. 61 percent of the total.

Number of films adapted as games amongst those with a budget over 100 million dollars (Source: The Numbers)

This large proportion of adapted films among the major productions -- particularly at the top of the range -- is also found outside Hollywood, for example in French film productions. Among the 11 French or French majority films with a budget above 40 million euros and produced through the year 2010, five have been adapted as games (The Fifth Element, Astérix aux Olympiques, Arthur et les Minimoys, Astérix et Obélix contre César, Arthur et la vengeance de Maltazard).

These significant figures illustrate Brunel University film professor Geoff King's remarks in his book New Hollywood Cinema on the role of blockbusters in the Hollywood economy and beyond, in the production of epics more generally:

"Successful blockbusters work like locomotives that carry the remaining projects along with them. It's these films that are most likely to be converted into video games for consoles or computers and sell large quantities of franchised merchandise."

Furthermore, box-office success also seems to be associated with diversification into video games. In a hit-parade of the 100 greatest box-office successes in the USA from 1937 to 2010 -- allowing for inflation and correcting for monetary erosion, as calculated by Box Office Mojo -- 50 films have been adapted as games.

If one takes a list of the top box-office winners world-wide, ignoring inflation and highlighting the last thirty years of film production, contemporary with the rise of video games, it becomes even more obvious that the adapted films are over-represented in the upper half of the ranking.

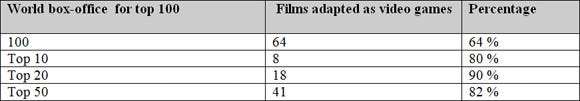

Number of films adapted as games among the top box-office successes of all time (world box-office) - (Source: IMDb)

Lastly, looking at the list of the top 200 successful films in French movie theaters from 1945 to 2010, 63 films were adapted as games out of those that passed the five million viewers mark -- including 10 French films, amongst the hundred or so French films or those productions enjoying mainly French financial backing in the ranking. These 10 actually represent more than half of the French or mainly French-financed films adapted for video games.

All these tables bear out the correlation between the positioning of a film production and its adaptability as a video game. The figures fully reflect the diversification policies implemented by Hollywood in the 1970s and sometimes picked up by foreign film industries: the growing investment devoted to tent poles, aimed at turning them into blockbusters and backed up inter alia by running the film as a video game.

These analytical features confirm how essential adaptation has now become in mainstream production: no economically ambitious project could currently do without supplementary back-up from a video game version. As King writes, Hollywood is constantly in search of ways to increase the potential profitability of films.

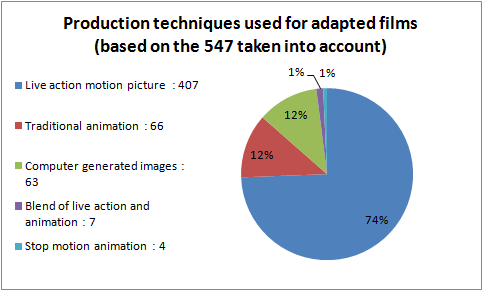

Adapted film items fall into five different categories: 407 films are live action motion pictures, i.e. three quarters of the corpus; 66 are traditional animation films; 63 are in Computer Generated Images; seven of them blend live action and traditional animation methods together; and four films are stop-motion animation. As they represent the main film production technique overall, live action motion pictures are also predominant in the case of films adapted as games.

This breakdown of adapted films in terms of the production techniques used must be seen in conjunction with an effect of technical convergence, due to the increase of digital special effects used in standard live action motion picture production. Furthermore, more than a third of the films shot in standard live action use visible digital special effects for the creation of decors (Tron, Lord of the Rings), character animation (Stuart Little) and visual effects (Jurassic Park).

Furthermore, practically all Hollywood productions in CGI since Toy Story in 1995 have been adapted as video games. Productions by Pixar, Disney/Pixar, DreamWorks Animation, and 20th Century Fox Animation are almost systematically adapted as video games.

This juxtaposition of digital techniques both in films and games confirms the industrial logic of producing items in which digital models devised for films can be re-used for programming video games. In fact, games adapted from CGI films benefit from technical gateways between the software used by the animation studios and that used by the development studios.

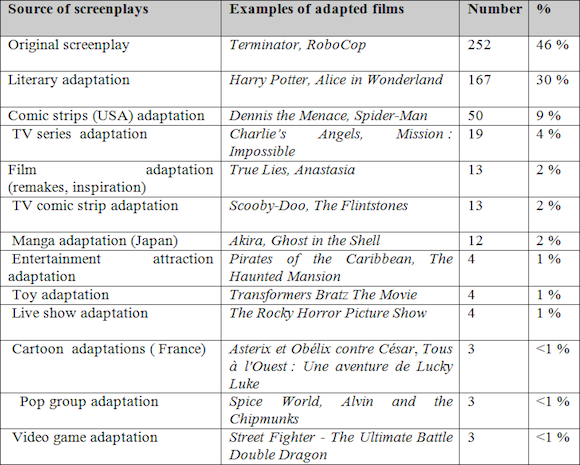

Screenplays for adapted films are largely original screenplays, in 46 percent of cases, and literary adaptations, in 30 percent of the cases. If they do not fall into to these two categories, they are borrowed from a variety of sources including television series, comic strips, successful music groups or, in a curious roundabout effect, video games. These films lie at the heart of multi-layered interactions between mass media and globalized audiences.

Sources of films adapted as video games

The source of inspiration for adapted films is strongly anchored in the popular youth culture nurtured by the American entertainment industry, another illustration of the inter-media dynamic governing the production of these video game items. Two main sources emerge: graphic arts (comics, manga, cartoon magazines) and television (series and televised animations).

The contemporary trends in Hollywood production are fairly well reflected in this corpus of adapted films: the adaptations of superheroes, led by Tim Burton's Batman; the reactivation of old successes in televised drama since the mid-1990s; and the most recent recycling of Disney items into films.

Some productions that use toys, video games and pop groups as their source are pitched at their traditional audiences: children and teenagers.

The high numbers of literary adaptations correspond to the way Hollywood film production traditionally works, lifting its subjects from books. A number of contemporary bestsellers appear in literary sources (Harry Potter, The Da Vinci Code, etc.), which once again seems to endorse video games as a source of profit, indispensable for any large-scale editorial project conducted on the basis of a successful novel, much like films.

As for the large number of original screenplays -- nearly half -- this would suggest that these cinema productions are designed both to meet the demands of the cinema as show business, and also to feature in other media, including video games (Terminator, Predator, Austin Powers, The Matrix Matrix and all the Pixar films).

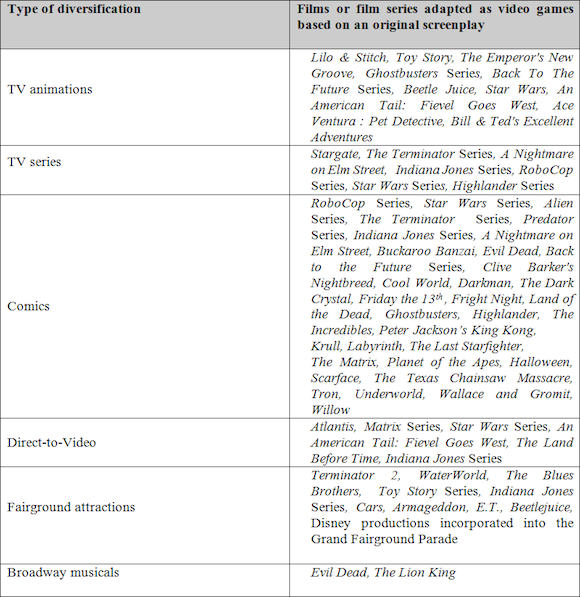

It turns out, anyway, that a large part of these films based on original screenplays give rise to a great deal of diversification in the sphere of entertainment and leisure. Without taking into account all of the novelizations, which are extremely widespread in the contemporary film industry and difficult to quantify, purely for the purpose of illustrating the degree of diversification, we have taken account of the developments in terms of television, video recording, comics, fairground attractions and Broadway shows, that is to say, the media that go beyond the story framework set up by the film.

Diversification applied to films or film series adapted as video games and based on an original screenplay

These diversification projects thus concern 70 out of the 252 original screenplay films (30 percent) and place these items, originally purely films, in the inter-media category along with the popular entertainment media, such as television and cartoon magazines. The same is true of literary adaptations, a large part of which are converted into TV animations or direct-to-video (almost all the adapted Disney animations from Aladdin to Tarzan), into TV series (MASH, Total Recall), comics (The Warriors, Total Recall, Starship Troopers), and fairground attractions (Shrek, Curious George).

The adaptation relationship between a film and a video game consequently cannot be reduced to a simple relationship between two media categories, but forms part of successive and simultaneous uses drawn from the same universe in different categories of media.

The transfer from film to game may operate in accordance with a genealogy that starts from the book to transit via the film and end up in video game form -- the latter being generally sterile except in its own domain -- but can also proceed in a rhizomatic manner, when the same item of intellectual property is simultaneously diversified on several media by different operators (Alien vs. Predator, for example).

Attributing a genre to a film is always a thorny question: a single film may be characterized by several genres. We shall accordingly reason here more in terms of generic labels than of genres, in the strictest sense of the word, with regard to films leading subsequently to adaptation.

We have used the classification by genre of the main online database devoted to cinema films, the Internet Movie Database, in order to arrive at a form of consensus on the genres employed by adapted films: the IMDb base attributes several generic labels to the same film, which provides coverage for all the genres it might may claim to. In quantitative terms, these generic production orientations bring out some notable trends from the extended corpus.

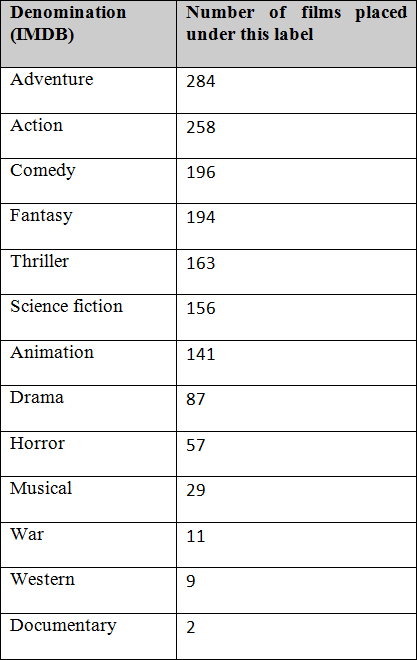

Categorization by genre of adapted films in accordance with the Internet Movie Database (IMDb)

Categorization by genres brings out the importance of the adventure and action categories, which characterize half of the adapted films. The denominations comedy and thriller respectively come in third and fifth positions, representing about one-third of the corpus; the favorite genres of New Hollywood are thus located at the top of the rating, i.e. the most spectacular and most popular.

The films giving rise to adaptations belong for the most part to contemporary spectacular films aimed at a teenaged audience, predominantly in the action and adventure categories, but also genres such as fantasy, sci-fi, animation, and horror, a type of product which clearly points to a young audience made up of children and teens.

Moreover, fantasy, sci-fi and horror are genres that have been developed largely since the second half of the 20th century by other media like popular literature, radio serials, cartoons and television programs. Inter-media circulation of film material falling under these headings is thereby greatly facilitated.

Lastly, the corpus points to two major trends in the Hollywood industry: the presence of some one hundred films that can be described as blockbusters or tent-poles -- those summer season super-productions released by the Hollywood majors -- and, on the other hand, a large number of sequels within the list of the adapted films.

Thus, 261 films of the total corpus belong to 117 different film series made up of at least two films. Amongst these series we find box-office hits from the 1980s like Star Wars, Alien,Terminator, RoboCop, Predator, James Bond, Rocky, Rambo,Indiana Jones, Back to the Future, Gremlins, Lethal Weapon, Die Hard, Ghostbusters; from the 1990s like Batman, The Addams Family, Jurassic Park, The Crow, Bad Boys, Austin Powers, Toy Story; and from the 2000s like The Matrix, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Star Wars, Spider-Man, X-Men, Charlie's Angel, Pirates of the Caribbean, Shrek, Ice Age, Fantastic Four, Madagascar, Transformers, and more.

As Geoff King points out, New Hollywood has set about reconstructing the genres in terms of the way they were used for producing blockbusters. Genres that had been limited to tight B-movie budgets were endowed with considerable financial resources to meet the spectacular features and prestigious casts of the summer blockbusters. These genres used for producing blockbusters can be summarized in a formula, which our extended corpus illustrates well, as "science-fiction/action/adventure laced with a touch of comedy".

Moreover, the foreign cinematographic styles significantly represented in this corpus outrageously dominated by Hollywood productions -- like French, British and occasional European co-productions -- appear above all because of mainstream action (Taxi 2 and 3), science fiction (The Fifth Element, The Earth Dies Screaming, Flash Gordon, Thunderbirds) or heroic fantasy (Krull, Kruistocht in Spijkerbroek) label. Regarding adaptations into video games, foreign films seem to stick to the Hollywood canon in applying to their films, based on the American model, the same type of diversification.

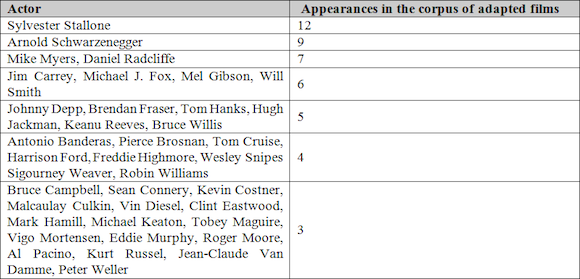

Adapted films use most of Hollywood's major male stars from action and adventure films, and from comedies too. We have listed the actor playing the lead role or the title role when this is played by a star. In the statistical data below, the over-representation of certain actors like Mark Hamill or Daniel Radcliff is due more to their involvement in films in several parts or films with sequels than to their star status. Other actors like Tom Hanks for Toy Story, Mike Myers for the Shrek series and Michael J. Fox for Stuart Little also appear in this inventory as star voices of the lead role in the original version of the film.

Actors on the playbill of at least three films in the corpus

The over-representation of male stars corresponds to the traditional role of actors in the Hollywood system, the only actress listed being Sigourney Weaver thanks to her role as Lieutenant Ellen Ripley in the Alien series, a rather masculine military role. Other actresses, very much in the minority, then appear in two films, like Cameron Diaz (Charlie's Angels), Sarah Michelle Gellar (Scooby-Doo), Jennifer Love Hewitt (Garfield).

The breakdown is very largely male-oriented, with well-built action stars like Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Tom Cruise, Vin Diesel, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Kurt Russell, and Wesley Snipes, which corresponds both to the masculinity model proposed by Stephen Kline in Digital Play: The Interaction of Technology, Culture, and Marketing, to describe one of the predominant features of the video game world during the 1980, and the pervasive influence of the "muscular heroes" of Hollywood movies during the same period.

The video game seems to have taken over the picture of maleness projected by Hollywood, in addition to going in search of the same figures in the cinema itself.

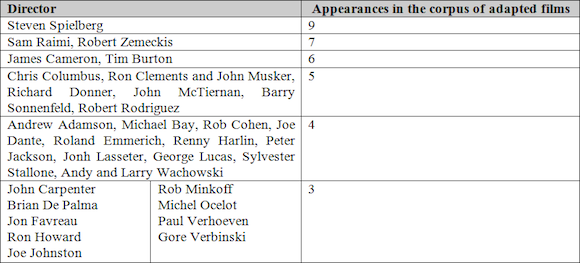

Directors on the playbill of at least three films in the corpus

The list of directors includes some movie brats like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Brian de Palma and, following them, an affiliated group including Richard Donner, Joe Dante, Chris Colombus, Robert Zemeckis, Ron Howard, Rob Cohen and Joe Johnston.

Several recognised specialists of screen epics like John McTiernan, James Cameron, Roland Emmerich and Renny Harlin are frequently associated with films adapted as games. Lastly, several specialists of animation from Disney or elsewhere (the Ron Clements, John Musker and Andrew Adamson team) as well as directors who have handled one or more film series (Gore Verbinski, Chris Colombus, Barry Sonnenfeld) are well placed in these ratings because of their involvement in the production of series.

By virtue of Kirikou and Azur et Asmar, Michel Ocelot is the only director on the list not to work for the American studios. This list also brings together the directors accustomed to top box-office results (James Cameron, Peter Jackson, Chris Colombus, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Sam Raimi, Tim Burton) to whom the majors entrust their most ambitious projects, and highlights the concentration of resources and facilities to guarantee the success of Hollywood productions at the box-office: substantial financial backing, pre-sold projects, spectacular genres, stars, experienced directors, etc.

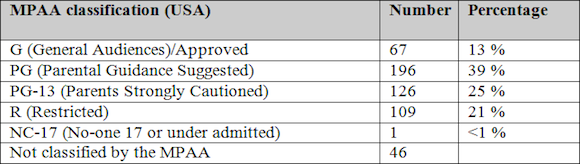

Lastly, the classification of films according to the recommended audiences indicates a corpus of production aimed at mainstream and family entertainment. According to the classification of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) in effect since the late 1960s, the groups G, PG, and PG-13, designating the greater number of adapted films, characterise 76 percent of the films adapted as games covered by the association. The films not covered by the MPAA either pre-date the entry into force of the classification system or are not screened in movie theaters in the USA.

The MPAA classification of adapted films

The films involved in the process of adaptation as video games are for the most part productions from Hollywood or with American financial backing shot outside the USA (runaway productions): American films overall represent 85 percent of the films adapted as video games. Financially ambitious productions are also over-represented: the films subject to adaptation as video games are for the most part large-scale productions in their country of origin, either in terms of the size of their budget or their box office success. Live action is the technique most frequently used by adapted films, although CGI productions are moving up.

The predominant approach in the adaptation process is the simultaneous release of the film and its adaptation, which calls into question the very principle of adaptation: video game adaptations are based on films that are in the process of being made. They are consequently based on pre-production features like the screenplay, the casting, the preparatory drawings, the decors and costumes, but never the content of the film.

These production constraints certainly explain why the corpus of 547 films adapted as games between 1975 and 2010 are substantially inter-media: each film is inserted into a network of vehicles that range from the source of the film (book, television, graphics) to its diversifications (novelisations, television series, comics). The video game adaptation has to be able to be based on an independent product other than the film that is used to design the video game, be it a novel like Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone or a series of comics like Spider Man.

We have also found that the balance of power between films and video games tilts strongly in favor of the game: it imposes upon the original story its system of values, its conventions, its own genres and its game priorities.

Finally, video game adaptations seems historically to have followed three paths with respect to the film narrative as the technical capabilities of video games have developed: they reduce the narrative to a game situation, then borrow from it the events with game potential; then finally, with the arrival of three dimensional modeling, they create an environment furnished with game and narrative opportunities from the film plot.

Translated from the French by Christopher Edwards.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like