Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Cinemaware built its reputation as one of the premier developers of cinematic games -- but ironically was destroyed in the transition to CD-ROM, and in this interview, founder Bob Jacob explains how.

[In the writing of his history of the video game industry, Replay, author Tristan Donovan conducted a series of important interviews which were only briefly excerpted in the text. Gamasutra is happy to here present the full text of his interview with Bob Jacob, who helped push games to their cinematic destiny with his Cinemaware studio.]

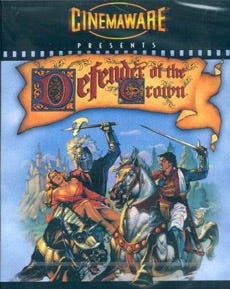

Bob Jacob's Cinemaware was a company ahead of its time, exploring the connections between film and games in the years before CD-ROMs through games such as Rocket Ranger, It Came from the Desert and, most famously, its 1986 debut Defender of the Crown.

He also started one of the first developer agencies and his career has now come full-circle as he is back representing developers across the world.

In the latest in a series of interviews carried out for Tristan Donovan's book Replay: The History of Video Games and being published by Gamasutra, Jacob explains how and why he sought to marry Silicon Valley and Hollywood -- and how that became the story of the company's demise.

You formed the Robert Jacob Agency back in the early days of the game industry. How did that happen?

Bob Jacob: In 1982 my wife and I moved from Chicago to Los Angeles. And I sold our business in Chicago and moved to California with no job, just some time to think about what I wanted to do.

So I started hanging out at the Thousand Oaks California Public Library and they had just gotten in a bunch of computers. I noticed all these kids were hanging out in this computer room and I said, "Well, this is sort of a phenomenon, this is kind of interesting."

So I made my way in there and befriended some of these kids. I was in my early 30s and they were about 12 years old -- my wife was very curious as to what I was up to (laughs). But I was trying a lot of games. I became a fanatic arcade gamer. I became hooked.

I bought a PC and I joined some local Southern California user groups and I met some programmers who I thought had some interesting software projects they were working on. But these guys were not very articulate, they really had no chance of trying to sell themselves or what they were working on. So I thought what these guys really need is an agent, someone who can talk and hopefully be persuasive and knowledgeable about software.

So what caused you to move from being an agent to running a games company?

So what caused you to move from being an agent to running a games company?

BJ: It was 1984. I got a call from a company called Island Graphics that had a contract to develop three graphics programs for the Commodore Amiga. This company and Commodore had a falling out, so Island wanted to place the project elsewhere.

I went up to see them and I had never seen an Amiga before. It was really cool. After seeing the Amiga I figured things were going to be different and I wanted to take a more direct approach to game development.

Cinemaware had two names. Cinemaware was the brand, but the company was Master Designer Software…

BJ: The initial name was Master Designer Software. I guess, my rationale for that name was I wanted to appeal to the egos of game designers (laughs). About a year into the company though, Cinemaware was what we were known by; everyone was calling us that anyway. So it seemed reasonable to just change the name of the company to our successful brand.

So what was your vision for Cinemaware?

BJ: Well the vision was I wanted to tell stories, but I wanted to give people a movie-like experience. So what does that mean exactly? There were a lot of implications to that, both subtle and not so subtle. I've never really explained this to anybody in an interview before, but I became obsessed actually with the idea of trying to create games that had the mood-altering quality of an arcade game, but had a story and some minor RPG aspects.

What I really liked about arcade games was that when I was playing a game I couldn't think about anything else. I couldn't think about my problems with this thing or that thing. It took up all my attention and it definitely became a mood-altering experience.

At that time, I thought computer games were very crude. A lot of them had keyboard interfaces, ugly graphics -- a whole host of elements that would really serve to kick you out of the experience. They were slow.

So I thought, "How do I address some of these issues and come up with games that I would want to play on a computer?" I wanted games that had a faster pace and put pressure on the player. I had a breakthrough creatively with the idea that I wanted action games but I didn't want action by itself. I wanted the action elements and the success or failure in those, to branch the story, to move things along. Action for a purpose. That was important to me.

I wanted to throw in some romantic elements. I just wanted to create a different feeling kind of game. I was in my early 30s at the time. I wanted to have a game that could appeal to more than just 12-year-old boys. So creatively that's essentially what I was trying to do and if you consider movies as a goal, then creatively it was great because we had all kinds of genres of movies to shoot for.

You know, we had knights in shining armor with Defender of the Crown, we had gangster movies with The King of Chicago, the Sinbad movies, the old-time family serials like Rocket Ranger, we licensed The Three Stooges. It became a really nice collection of creativity.

Your ideas coincided with the arrival of the Amiga, Atari ST -- that whole mid-'80s generation of computers. Did you need those computers to get close to trying to achieve your vision?

BJ: Not necessarily. Rocket Ranger, Defender of the Crown, The Three Stooges -- there's versions of those all running on the original Nintendo and there were versions of most of the games running on the Commodore 64. It was possible to do it on a less complex system.

But you concentrated on the Commodore Amiga in the end?

BJ: Yes. I loved it. It was probably my downfall ultimately, but I was sure we could do the best graphics available in the world at that time.

I was a big believer in trying to push the graphic quality of games, and we could do better graphics on the Amiga than any other system. So I guess my ego became inextricably bound with the Amiga. I really wanted it to succeed.

Tell me about the creation of Cinemaware's first game: Defender of the Crown.

BJ: Master Designer Software was incorporated in December '85 or January '86 -- I can't recall. I was able to secure a distribution agreement with a company in Chicago called Mindscape for the US rights. In my agreement with Mindscape we said that we would have Defender of the Crown ready to distribute by October 15, 1986 and it really had to be ready to go. We thought we would make that date.

A software developer in Salt Lake City called Sculptured Software, which later went on to do some pretty big things, they were the first developer of Defender of the Crown. Well, lo and behold, July 1st 1986 rolls around and those guys are like nowhere. I mean literally nowhere. It was a disaster and I was faced with a situation where I had to ship this game.

So I hired John Cutter, he was the first actual employee of Cinemaware. The first six months of that year my wife and I were the only employees of the company. John's first job was to fire Sculpture Software. I then picked up the phone and got hold of RJ Mical, you know RJ Mical?

The guy who helped create the Amiga?

BJ: Right. He wrote the operating system for the Amiga. I called up RJ in early July and said, "if you can program this game and have it ready to go by October 15th, then I'll give you $26,000." Now this was 1986, $26,000 was a reasonably large amount of money. He said, "I'm your man."

So the Amiga version of Defender of the Crown, which from a gameplay, and from a QA aspect, is probably the weakest version of the game, was actually programmed in three and a half months.

So how did you feel about the end product?

BJ: It was the first game that actually showed the power of Amiga graphics. It was beautiful. Up until that time, the Amiga had featured a lot of games that were basically Commodore 64 games with really unenhanced graphics. I would say literally every person who owned an Amiga bought that game. We had almost 100 percent total.

Was Defender of the Crown Cinemaware's biggest seller?

Was Defender of the Crown Cinemaware's biggest seller?

BJ: It was definitely Defender of the Crown. That was the gift that kept on giving. I don't think it was our best game, but it was a phenomenal success. You can't control those things, you just ride them and you get carried away with it -- and it was fun.

So after that development work became internal rather than contracted out?

BJ: To start the company I put four titles in development on day one: Defender of the Crown, King of Chicago, Sinbad: Throne of the Falcon and S.D.I. They were contracted with outside development. We had no one internal.

But the initial feel for the titles was strong enough that we were able to start bringing in staff to work on games that we could develop internally. The second round of titles came out using internal staff -- Rocket Ranger, The Three Stooges. They were all in the second wave.

From the interviews with you and others at Cinemaware from the time, it seems as if you were trying to apply a Hollywood production methodology to game development -- doing storyboards and so on. That's pretty standard in the industry now, but was a pretty new idea then.

BJ: Let me describe what my role was in the company, first of all. Analytically, I would say that my two biggest strengths are that I'm a pretty creative person and I'm a good sales guy. And probably the world's worst manager, (laughs) which I had to learn through painful experience, unfortunately. I say "creative" only because I did have certain things that I wanted to do with the games I was involved with.

In terms of production methodology, yes, we would have story meetings, we would flowchart the game, we would come up with storyboards. The games we were doing were different to the other games people were doing at the time. They were a lot different. So we really had to figure out where we were going with the game.

We weren't doing platform games, we were doing games that had storytelling and role-playing and action and this, that and the other thing. So if we didn't know where we were going it would be a disaster, so it forced us -- I think -- to a level of oversight that was rare at the time in the industry.

So it was more the type of games you were creating that drove the design model rather than you looking to Hollywood and going, "Oh, that's how they do, we'll do the same"?

BJ: Yes, exactly. We tried to learn from people who were doing things that were somewhat similar.

I've read that you got your own likeness into each Cinemaware game - a bit like Hitchcock appearing in his films. Is that true?

BJ: It's true actually. But it was not a mandate that I dictated -- it was something that the employees did as a lark.

So when did you first find out?

BJ: I think I first found out in TV Sports Football. There was a cutaway scene to a crowd shot and there I was in the middle of the crowd screaming my head off. It was quite satisfying to my ego at the time.

TV Sports Football is interesting because it's where video game sport has gone -- rather than trying to simulate the sport it simulates the TV coverage.

BJ: (Laughs) I think of EA Sports and I go "Yes, that was my idea." (laughs) Early on I saw that people relate to sports through television and the way to do it was to emulate the TV broadcast.

Like in TV Sports Football we had the scores in other games around the league in progress, we had a halftime show, we had marching bands, we had announcers, we had everyone. It was way ahead of its time.

With your choice of the Amiga as the company's primary focus, the European market must have been particularly important to Cinemaware…

BJ: It was. We were typically selling more action games in Europe than we would in North America. The UK and the German market in particular were very strong.

How well known is Cinemaware in North America? The Amiga was a mainstream format in Europe, so you were a mainstream company in Europe.

BJ: Don't forget, we also did games on other platforms. All our games were cross-platform. All of our games were released on PC and Atari ST. And most on the Commodore 64 and some on the Macintosh. So we weren't exclusively tied to the Amiga.

We generally used the Amiga as the target platform for original development. Here's a thing that I was right and wrong about. I was absolutely right that the machine that would revolutionize the game business was released in 1985. It was. But it was the NES, not the Amiga. (laughs). You know, I had opportunities to get involved early on in the NES and I didn't.

Everything's easier with hindsight…

BJ: It certainly is.

Cinemaware also imported European games to the US…

BJ: Spotlight Software? Yes, we were a company, at one point, of over 50 people and we weren't releasing enough titles to be able to support that number without selling more games. So to help alleviate that, we created a company called Spotlight Software and we bought some pretty hot UK and European built titles for sale in North America. Probably the best-known title was Speedball. It was quite successful.

What did you make of the games being made in Europe then compared to those in the US? They were still very separate territories at the time.

BJ: Fortunately, the games that we were doing were able to sell around the world, which was unusual in those days. I mean, the themes were pretty universal, so everywhere from Japan and Europe to North America were successful territories for us. Back when Japan was big, most European games were being built for the European marketplace. That's still true of, like, Germany. A lot of games built in Germany stay in Germany.

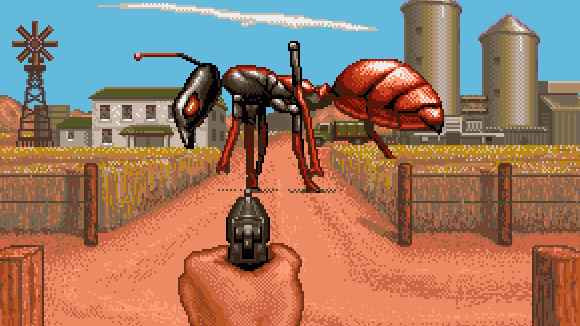

It Came from the Desert

It Came from the Desert became Cinemaware's first CD-ROM game and was one of the earliest CD games. What was the appeal of working with CD?

BJ: It was clear the CD-ROM was going to be the future of games. We saw that early on. At that point in time, people like Sierra were releasing games with like 10 disks in it. It was getting crazy. So clearly we needed more storage and we could see that CDs were going to be the future. And so we thought, "Well, if this is going to be the future, why not jump on it early?" So we did, and it was one of the first CD-ROM titles.

How did it change the development process?

BJ: With the addition of CD we were able to dramatically increase the amount of voice that we had. Voice had been in a lot of Cinemaware titles, but we were obviously constrained by the limits of floppy disk-based media. But once we got to a CD-ROM, we could open it up and so a lot of the stuff that was done through text in the floppy disc version of the game was done through voice on the CD. I think it made a much more movie-like experience.

There must have been very few actors with experience on video game work. How much of a learning curve was it?

BJ: We got actors that had experience in radio. So it was still kind of crude and they weren't big-name people, but they knew how to operate around a mic and a sound studio. So we took advantage of that. By today's standards it was very crude, but for the time it was a breakthrough.

My understanding is NEC funded It Came from the Desert because they wanted it for the PC Engine. What's the story?

BJ: In retrospect this was the decision that killed Cinemaware. We sold 20 percent of the company to NEC in Japan. Why were they interested in investing in us? Well they saw us as a high-quality developer and they were going to be releasing the PC Engine in the United States under the name TurboGrafx-16 to compete with the Genesis and Nintendo.

So at the time I thought, "Hey, getting some money for this would be good" and being partially-owned by a Japanese company that could acquire us all at some point for a bunch of money, what could be bad? So we said yes and did the deal. We obligated a significant proportion of the resources of the company to doing development for NEC on the TurboGrafx-16.

Well, ultimately, the TurboGrafx-16 failed miserably. The Americans who directed the involvement with Cinemaware were all summarily fired and we had run up some debt for the company doing some of these trial games in the expectation it would pass. All of a sudden we were in very bad straits.

How much funding went into the CD version of It Came from the Desert?

BJ: It was a pretty expensive project and I think it cost maybe $700,000, which in those days was a large amount of money.

How many times more is that than your normal development budget at the time?

BJ: On Genesis cartridges, you could do a really good game for $150,000. So I would say it probably cost four or five times more than a typical cartridge game.

So what happened when Cinemaware ran out of money? I read in one contemporary article that Mirrorsoft bought the company.

BJ: No. Mirrorsoft was our distributor in the UK, and we had a really good relationship with them. When it was obvious the company was going down, I was faced with the unlucky task of trying to sell off its assets. So Mirrorsoft may have bought an asset or two, but so did Electronic Arts, so did NEC, so did a bunch of people.

What did you do after Cinemaware?

BJ: Oh, I faced a real problem because I was living a certain lifestyle and heavily in debt to a bank. So the first thing I had to do was pay off all these creditors, including the bank. I was able to do that by licensing off all the assets of the company, but then I had to have a job so I started a console development company called Acme Interactive.

I actually went over to the UK. Back then -- this was like '90/'91 -- there was a weekly game newspaper published in the UK called Computer Trade Weekly and I ran a couple of ads in there saying "I'm coming over", and based on that I had like 10, 15 programmers out of the UK. Far more than in the U.S.

Acme probably became the most hated company in British software. I took a bunch of people from Ocean and some people out of Derby [home of Core Design] and did something that I should have done earlier -- I turned into a Genesis developer.

What games did Acme make?

BJ: Well, let's see. We did Evander Holyfield's Real Deal Boxing and the follow up. That was a million U.S. seller. We did Batman Returns, Joe Montana Football. We did a version of BattleTech on the Genesis, which was a very, very good game. The development guys went on and became the founding team of Neversoft. I took Acme and merged it with a comic book publisher called Malibu Comics in, I think, '92. Then in '94 the company was sold to Marvel Comics.

So how did you end up going back into work as an agent?

BJ: I got a phone call one day! In 1996 I got a call from a former employee of mine, a Scotsman named Ian Morrison who was working for Sony in Santa Monica. They wanted to move, he didn't want to go. So he had put together a concept for a game and actually knocked on the doors of some publishers trying to sell it. He seemed to get some interest, but couldn't get a deal closed and he asked me if I'd be willing to help him.

So he came over to my place and I looked at what he had. It was very much like Robotron, only in 3D. So I said, "Here's an idea, look through to Midway and try and sell them on the idea of bringing back Robotron in 3D." And they bought it. So now he had a developer studio called Player One and I became his agent.

Following that I got a call from another former employee -- David Todd -- who had kept on a number of the Cinemaware guys at a studio. We got together and -- this is probably the single greatest sales job I ever did -- I persuaded Nintendo of America to give him StarCraft on the N64. So now I had a company called Mass Media and I was an agent.

Clyde Grossman, who had run Sega of America and had been head of development, had also become sort of an agent. So we decided to join forces in '97. And so Interactive Studio Management was formed and here we are almost 15 years later representing some pretty major developers.

Which developers are you representing at the moment?

BJ: We represent Digital Extremes, the co-creators of Unreal, Silicon Knights -- we got their creators. We represent Asobo of France, who did Fuel for Codemasters. Darkworks in Paris. I think we have 11 developers. We've done like over $400 million of sales in the last 10 years. It's been an interesting run and being an agent has been good -- it's really probably the job I was born to do.

Given that you're still involved in the industry today, looking back at what you did with Cinemaware do you see the things you pioneered there that are now common practice?

BJ: Oh absolutely. If you look at Call of Duty, for example, or even Assassin's Creed -- people are trying to do games that are very movie-like experiences. Obviously they've been able to achieve much more than I was, but they have better technology and more money to work with. But clearly I think the vision of what I wanted to do 20-plus years ago, is now being seen.

I think, in a way, the success of franchises like Call of Duty really do vindicate what I had. I mean, I've had a great career and I have no complaints -- I've had my ups and I've had my downs, but overall it's been a fantastic chance for me.

But I will say that on one level I suffered the fate of many pioneers: I was too early. I knew what I wanted to do. The technology wasn't there then and was not going to be there for a while, but if you look at the games today and what we were trying to do there is a pretty sophisticate opportunity. At the time if people asked if Cinemaware was a genre, I would say "No, Cinemaware was the future." Cinemaware is where games are going to be and ultimately I was right.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like