Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Developer of iconic games such as Demon Attack (Imagic, Atari 2600), Night Trap (Digital Pictures, Sega CD), and Petz (PF Magic, PC) speaks about his career and the evolution of games and game technology.

[In his video game history book Replay, author Tristan Donovan conducted a series of important interviews which were only briefly excerpted in the text. Gamasutra is happy to here present the full text of his interview with Demon Attack, Petz, and Night Trap developer Rob Fulop.]

Rob Fulop started his 32-year career in games at Atari recreating coin-op hits like Space Invaders for the VCS 2600. He went on to co-found the game publisher Imagic, and through it delivered a smash hit with his 1982 game Demon Attack, only to see the company felled by the U.S. game industry crash of the 1980s.

Since then he has produced one of the earliest online games, devised the first popular virtual pet game, and designed the infamous Night Trap.

In this interview, Fulop talks about why Atari chairman Ray Kassar was right to call him a "high-strung prima donna", why you can't be bingo, and why he always consults with Santa.

How did you end up making games?

Rob Fulop: Well, I've made games my whole life. I was making them when I was a kid. I would make up board games with checkers.

We had a toy called Carrom. It was a board with four pockets and with a big bunch of rings. The system was capable of playing a thousand games. You could play checkers or chess with it, you could play pool, you could play a million games with this thing. Snakes and ladders, whatever. So basically I just made up games for years.

The Carrom set, it really entertained me for my whole childhood. So I invented games. I made a little mini-golf course out of cardboard boxes. I've just been making games forever. So Atari was a very natural place for me to go. It was a no brainer.

Did it seem logical to start making games on a computer?

RF: Very logical. I found computers when I was 16 years old at our high school. They brought in a terminal that showed us what a computer did. The first thing we did was to start making things like tic-tac-toe. So when computer games came out, to me it was just, "Okay, that makes sense." I didn't expect them to go boom. That was never expected, but to me it was completely natural.

That's interesting. Most of the American game designers of your generation I speak to seem to have had access to computer terminals at school, whereas computers didn't really make it into many UK schools until later. Was it some kind of government push?

RF: I don't know. We had hooked up to the Lawrence Hall of Science, which was a local technology museum, and they put terminals in every school. Have you read Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers? It's a book about talent and where talent comes from. Basically they traced the background of technological geniuses and they are all guys who had access to the tools when they were young. Not that I'm a technology genius! But I certainly got real joy from some of the stuff like that. I was lucky I got to play on a computer terminal when I was 15, 16.

So what was Atari like to work for?

So what was Atari like to work for?

RF: It was wild, it was wide open. They'd say 'make a game, any game'. It was really weird given how much control there is now and how much you have to write the whole spec.

At lunchtime people would go around and play other people's games. If more people were playing your game, the man would say 'okay, invest more in that one'. That was literally how it worked. There was no structure at all. But if you didn't make a game in a year or so they would kind of ask you to leave.

How do you make a game under those circumstances where you just experiment and see if it sticks?

RF: You typically start off by copying a game. If you look at my history, my first three or four games were copies of arcade games. Like Night Driver, which is a driving game where, basically, it's 12 dots coming at you. I did Missile Command, Space Invaders. These are not mine. I didn't invent these games. I didn't try to write an original game.

After never having made a video game it's crazy; I didn't think I could do it. So you copy someone else's game and then you start modifying it. You start changing stuff around or combine two different games to make a new game.

There was a game called Zap, it was in an arcade, where something in the middle would shoot balls four different ways and you had to block them. It was a reflex game. We turned that into a spaceship and made it into a science fiction-themed game. So you re-theme it, re-purpose it.

We found, after five years or so, that there were literally five or six basic games and they're based on things that we like to do. Going fast is a basic game that people like to do -- they like to go real fast. So you'd see that game a million times. You still see and it's fun.

There's something in movies called a premise of a film and it's like this if you boil it all down. Star Wars, the premise is good conquers evil. Any movie about a gangster is "crime doesn't pay." At the end the guy gets blown away. That's how it ends in every bad guy movie, he dies at the end.

So games -- they have the go fast, the kill everything. There's the genre of games like adventure games and World of Warcraft: treasure hunt. It's basically "find the treasure." You find the door is locked, go find the key, open it and now you get the treasure. So there's treasure hunt and then you combine them, you have treasure hunt where you kill everything or treasure hunt where you go fast.

It's a bit like fiction, that idea that there are only seven stories that can be told…

RF: That's exactly right. The other one is Pac-Man. The fun thing about Pac-Man, the exciting moment of Pac-Man is when you eat the power pill and you become the aggressor. So you're running and running away and then you eat this thing and now you're chasing them -- you turn the tables. You swap the tables around; you go from being pursued to being the pursuer. It resonates with so many people.

Why did you end up leaving Atari for Imagic?

RF: It was pure money, pure greed. We felt that we were making things, we were artists, we were authors and we weren't paid like, or feel like, authors at all. We weren't compensated based on how good our work was received. Our name wasn't on any of it. If you're an author they put your name on the book and that's kind of how it works. They weren't doing that and so we left. Basically I wanted my name on my work, that's all.

When I interviewed Manny Gerard, the Warner executive who oversaw Atari, he argued that people like you and the Activision founders were entrepreneurial and even if Atari gave you what you wanted you would have left because entrepreneurial types don't stay in corporate environments.

RF: Well, I think giving me 10 cents per game, that would have been fine. I mean, I was 23 years old at the time, and it's not asking much. But the management didn't know there was a difference between one brand or another. They had no idea that there was anything involved in making these. They just thought games just appeared.

Hence Atari chairman Ray Kassar's comment describing Atari's game designers as "high-strung prima donnas"...

RF: Well we were. We totally were. Isn't every actor or actress? So were The Beatles, so was Michael Jackson. I mean everyone knows Michael Jackson was the ultimate highly strung prima donna. People that create things are kind of whacked-out, highly strung prima donnas. That's kind of how it works, right? You're a writer, aren't you a highly strung prima donna?

[Laughs] Yes.

RF: That's right, it's no big deal. I remember feeling not insulted at all.

Was it easy for Imagic to get the funding it needed at the time?

RF: I wasn't involved in that. Someone else did that and invited me to the party. My boss he said "I'm leaving, do you want to come with me?" That was basically how it worked. It took me, like, two seconds to say yeah.

Demon Attack

Am I right to think that you wrote Demon Attack, Imagic's first release?

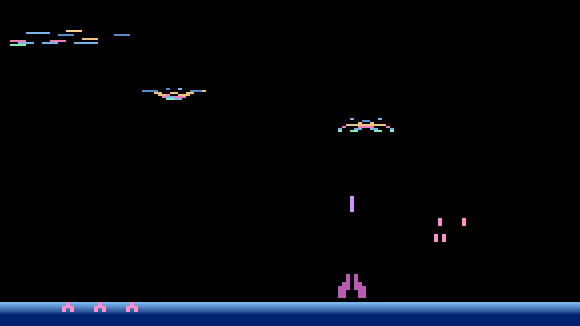

RF: Yes, that's right. It was really cool. It was one of the first things I think that really felt like an arcade game. It was modeled after Galaxian. Basically it just looked cool. I learnt some graphic tricks to make things jump out. So it was "Wow, the Atari -- I didn't know it could look like that!" So that was big. It won that year's video game of the year with Billboard magazine. That was a big deal.

How did it feel to be in the industry at that point in the 1980s? It was a massive boom time for games in the U.S.

RF: Games were the thing. If you watch Blade Runner there was Atari in there; they presumed that Atari would be around forever. It should have been. I mean, if ever there was a bungled franchise it was Atari. They had the best brand name of any company. You know, what happened, there's no excuse for that. They just completely screwed it up.

Did you think it would go on forever in the period before the crash?

RF: Of course. Like any hot thing, like the internet, the people who are there, they just assume it's going to go on forever. And, especially when you're young, you can't imagine that anything will change.

So it must have been a shock when the bottom fell out of the market.

RF: Oh yes, it was a total shock. I still haven't gotten over it.

When did you realize that it was all going wrong?

RF: My best friend Michael, who was a reporter for Rolling Stone, realized it at a Consumer Electronics Show when he interviewed this guy. He did the interview with a guy who bought all the games that people weren't buying, a consolidator or whatever. He would buy all the games that the retailers couldn't sell and sell them for a lot cheaper. When they appear, then you know.

Michael talked to this guy and this guy was telling him that he can't believe how much hype there was around the games and how many games he was picking up. That was a leading edge indicator. All the retail stores are pretending that it's all cool, but meanwhile they're selling tons of unsold games to this guy.

That was, to me, the first clue that there is something wrong here. You know, this guy shouldn't be doing such great business. But there were too many games being made by too many companies and there wasn't that much you could do with the Atari system. A lot of kids bought a game, but when you're 12 years old and you spend 50 bucks on a game, it's a lot of money. If it's not great you don't buy another one. It's like a major, major, major purchase -- it's like buying a car.

Definitely, I remember spending weeks and weeks saving up for a game. You'd go buy it, come back and go, "Damn, I picked the wrong one."

RF: Right or you research like crazy or you've got to pick one Christmas present. Music is something you can sample on the radio or iTunes -- you sample it first. How often do you buy music without having heard it? I never do.

When you go buy food at a fair, somebody gives you a little taste. If you like it then you buy it. But video games you've got to play it before you know, and back then you couldn't. People were buying based on the cool thing on the box, and that's not the right way to sell an experience. You can now, finally, download a sample and play it for five minutes. That's how you sell a game.

Imagic lasted for a few years after the crash but never seemed to recover…

RF: Yes. Things went on for a while. They tried to make computer games -- a shift to making games for the Commodore 64. The Commodore 64 was the big one. The problem with those games was they were on a floppy disk, very easy to copy.

It's not the same thing as selling a cartridge for 30 bucks. It was a hacker business; people would steal your game. They wouldn't buy it, they would copy it. People were writing games in BASIC and trying to sell them. It was just a very splintered market.

After Imagic you got involved with pre-internet online games at Quantum Link, which later became AOL, creating RabbitJack's Casino for them. How did that come about?

RF: I got introduced to the president at a trade show, a CES show, and I told him they should do a casino. If you look at my work, I've never really made up that many games. I never really invented a lot of games.

My big thing was to find me a game out in the world and put it into an interactive format on the computer and make it really fun. Inventing a brand new game -- I've never done that. All my work I kind of just take from another game.

But that's like most games; people who come up with something truly original are pretty rare.

RF: Well, it's like checkers. Do you know how long it took to design? Like 500 years. It took endless iterations. Like chess. Chess, through thousands of years, it's evolved. If you look up the history of chess, there are millions of variations.

Those old online networks were hugely expensive to log onto. Why did you think a casino would work? Did it work?

RF: AOL was new. They were charging four bucks an hour. It was an expensive experience, so they just wanted other entertainment to occupy people. It worked in their context; it worked. It wasn't mass market then. It was a pretty niche business.

We designed it to keep you logged on as long as possible. We built the slot machines to be very generous slot machines. The slot machine of RabbitJack's was designed to give you chips, right, so you'd win a lot and you sit there and you go, "Wow, I've just won this money on the slot machines." You know, it's the greatest casino in the world.

Was it multiple players?

RF: Poker, you could play poker with five other guys. Blackjack too, and bingo. Bingo wasn't a game that you played alone, you all played bingo together.

I didn't know Bingo was part of it…

RF: Yes, it was a very easy game. You don't have to do anything. It's a simple game, a brain-dead simple game to play. Everyone knows how to play it. You can entertain an infinite number of people playing bingo. If you have a prize, it's pee-in-your-pants exciting. You win the way and you're waiting for B4, you're like, "Oh my God!" You won't even leave to go to the bathroom, you sit there waiting for B4, like an idiot.

And you can entertain a million people, an unlimited number -- a hundred people, a thousand people. It's easy enough to scale. There's not many games like that. Good luck in trying to figure out a game that you can play with a million people or a hundred people or five people that's exciting and fun and a new game every five minutes. Go ahead, try to find that game.

Yes, especially when it's so simple to play, too.

RF: Right. I mean, you can't beat bingo.

After AOL you got involved with Hasbro and its NEMO console, which was a VHS cassette-based console. How on earth did that work?

RF: We figured out a way to put multiple tracks on a video. You could have as many tracks as you want, and the more tracks you had, the more of a sad display you got. So if you had two tracks you would see every other frame.

But if you had 30 you can only see 15 frames per second, because on the video it would be like a shuffled deck. You would see only these. So it looked a little fuzzy. If there were four tracks then you would only see eight frames a second right, so it would look kind of weird. But that's how it worked, it was screening. It was all going in real time.

Night Trap

So would the games have played something like, say, Dragon's Lair?

RF: Dragon's Lair was a branching game. You got to a point where you either go that way or that way. But because the video tape is running you can't just sit there and wait for the user to decide left or right. Dragon's Lair was a laserdisc, and a laserdisc can jump.

So that's why we made a game like Night Trap. In Night Trap there's a house and stuff going on at the same time, all over the place and you can jump to a different place whenever you want. That was designed to work on tape.

The system works, the story is moving, and you can just move around in the story. That's where Night Trap came from. I mean, it's been critiqued a lot. It's not that great, it's not like it would be playable as a game, but it wasn't designed to be.

So what happen to the NEMO? Why did Hasbro pull the plug?

RF: It was too expensive to make these things. We had to make a movie. It's hard to make a movie. I had to get them to build houses that had traps in them. If you look at Sewer Shark, we shot the ending in Hawaii. We had to fly everyone to Hawaii. It was just very expensive and ultimately the box, cost too much to build.

The retail price for it they had to get was like $149 or whatever. It's all about the retail price point, and it cost a lot to make these things and there was a problem that they would break a lot. And, ultimately, the games weren't fun enough to justify the purchase price, and they weren't that replayable. You can play Mario a thousand times and Night Trap you play it 10 times. It's more of a rental than a purchase.

So after that you formed PF Magic and started doing multimedia CDs. How big a shift was it moving from cartridges and floppy disks to CDs?

RF: In my view the graphics became more expensive, that's all. With CD we had to get photographers and shoot photographers and hire actors to appear in the photographs. So from my end as a designer, more and more of the budget was spent on the presentation of the game than the actual mechanics and core of the game.

And we couldn't experiment as much because once you get those assets filmed, once you have those graphic assets created, you can't easily create other ones. If they're very simple graphics like a Pac-Man, you can make a Pac-Man do anything you want the next day.

But if it's a three-dimensional avatar you've got to know exactly what the avatar needs to do. And if later you said "Oh, now he needs to do a back-flip," well you have to go and hire the actor back to come and do a back-flip or whatever. So it meant that we couldn't try as many things.

So the extra storage space didn't really open up new possibilities?

RF: It did, but we used it all up in about 10 minutes. We were like, "Wow, we can do this -- then we can do a roller coaster thing!" So great, how much roller coaster footage can we put on? So we put on 20 minutes but that's not enough, we needed more than that, so now what do we do? And video's expensive.

And creating video must also have required skills that game developers didn't need or have before.

RF: The massive change from a design point of view was you had to know in advance, before you built the game, exactly what graphics you needed, which made it really difficult to invent new games. Very, very difficult. No one figured out the game of chess by saying, "Okay the knight's going to work this way, the bishop's going to move that way, the rook's going to do this."

How did the move away from video footage to polygon 3D affect things?

RF: 3D was even more expensive.

Really?

RF: To create models, yes. We had to learn to make models and how to move the camera and the models. And there were bandwidth issues. I was never impressed with 3D.

What didn't you like about 3D?

RF: What I didn't like about it is I thought it was a visual trick that looked cool for about 10 minutes and then, I believe, your brain, when you play, starts not seeing the graphics after a while.

What you see in your mind's eye inside is just basically symbols and shapes. The graphics are kind of like the candy. What really is happening, you don't appreciate. Those graphics catch your eye right away. But if you play it for more than 10 minutes you don't even see those graphics anymore, I don't believe. That's why 3D to me looks like a lot of fuss, and the game itself wasn't that much better.

So how did PF Magic end up creating the Petz series?

RF: PF Magic was based on a piece of hardware we called the Edge. The Edge was a piece of hardware that you hooked up to your Genesis and the telephone and you can play games. The idea was that you could play Street Fighter with your friend across town. That's what it was about.

So AT&T put up the money, and Sega was a partner, and that was our big thing. We were going to make this system and make games for it. That was the idea that threw up PF Magic. But then AT&T pulled out because, again, the machine was too expensive to build. So now we were left with about half of our funding and we just had to figure something out, which was when we came up with Petz.

What was the inspiration for Petz?

RF: There are two vectors that created the path. Vector number one was I had made a game called Night Trap, which had been released at that point by this other company, Digital Pictures. And it was becoming very controversial because we had shown imagery of girls being dragged off by monsters and there was a big political scandal around Night Trap. To me personally, it was kind of silly.

It was also deeply embarrassing, because friends of mine, my parents and my girlfriend, didn't really get games. All they knew was that a game that I had made was on TV, being talked about as being bad for kids. And, you know, Captain Kangaroo came on TV and said, "This is bad for kids." It was horrible.

At the time the Captain Kangaroo show, every kid watched it. He was just an icon of kids' television. I watched him, I think he was on every Saturday morning. Anyway, they dragged him up and he said something bad about Night Trap and it was just embarrassing. I fell out with my girlfriend about it, because I thought it was completely bullshit criticism.

But I decided that the next game I made was going to be so cute and so adorable that no one could ever, ever, ever say that -- it was, like, sarcastic -- what's the cutest thing I could make? What's the most, you know, sissy game that I could come out with?

Then at the same time it was in December, and I would always go at the end of the year to see Santa Claus at department stores. You go to Santa Claus and he'll tell you exactly what's going to sell that Christmas. He knows better than anyone, because all the kids talk to him. His job all day is to ask kids what they want. So if you want to know what's going to sell this year, just go and talk to Santa Claus and this guy will tell you exactly what's going to sell. I did that every year.

So we go into Macy's, talk to Santa, and actually he goes, "It's still the same, the most popular thing that kids ask for every year is a puppy. For the last 50 years." So the two just came together. It was make a puppy. That was really how the idea came out.

And then we also had this technology. The first game we made with 3D was called Ballz. It was a fighting game and all the characters were made out of spheres. You know, the sphere is the only thing that wherever you put the camera, it's still a sphere. You don't need to store different images of the sphere. You just need to know the sphere has a radius of five and is blue and you can create it.

So if you build the whole character out of spheres, all you have to do is keep track of is how the spheres connect. So we had a patent on that, we built the whole world using that. Then we made it into a pet. We built it into a dog. People loved it.

It doesn't sound like it was inspired by any previous games at all…

RF: It wasn't; there was no computer pets before that. But about the same time, though, Japan had come out with the Tamagotchi toy. The two were kind of built at the same time. I don't think we even knew about each other. It's kind of interesting when designers think along the same lines, though. Ours was on the computer, theirs was on a little hand held thing.

It just struck a nerve. People liked it. People really liked it. I mean, it's a very obvious thing. It's a puppy dog. The way we sold it was, we'd give it away. We sold it the same way real puppies are sold. We give it to you for 10 days and ask for it back. Give a puppy to a kid and ask him for it back five days later, just go ahead see what he says. In sales this is called "the puppy dog close."

We gave you five days' worth of food, and if you want more food you've got to call us and we give you a whole lifetime supply for 20 bucks. It's not little puppies that don't cry, you know. They'd whimper and cry and then you have to delete it and it asks, "Do you want to delete me?." I mean who can say yes?

No, you sit there with it whimpering and your little puppy would say, "Do you want to delete me?" And who can delete it? It's cruel, it's a little puppy and you won't feed it. It's impossible to say yes, so we sold a lot of them. We sold a ton of them.

It was completely viral, and then after a couple of weeks your pet would have a puppy, and then you could keep it yourself or give it to someone else. You put your floppy in and picked your puppy, and give it to a friend, and so there is another spawning. That was the way it works; it was great.

The virtual pet has become quite an established genre now, Nintendogs, etc.

RF: At this point yes. Nintendogs sure. Petz is still a brand. Ubisoft still puts it out every year. They're not as lifelike as they used to be, because they became more realistic. If you see our original dog, it wasn't realistic at all but it was really likeable. It was cute, it was loving. The ones now look like real dogs but because they spend so much bandwidth on making it look real it's hard to make the thing do a lot of different things. It's a trade off.

What do you think it is that attaches people to these virtual pets?

What do you think it is that attaches people to these virtual pets?

RF: It's that they need you. You're needed. So you come home and this thing is like, in your face. It needs you. If you're not there you know that it's going to be very unhappy -- or it could die, right? Isn't that why you get attached to plants and puppies and kittens? I don't think a virtual pet is any different, we just create them. And when you come home, what do they do?

Jump up and down, somersaults…

RF: Right, and you love that, right? So that's what we get our puppy to do. Whenever you move your mouse he'd follow your mouse. They can't wait to be petted. When you put them out they come running over, right? That was their biggest excitement. Basically I think people are attached to those things to be needed, which is why a baby is the ultimate.

I was reading an interview you did with Wired back in '94, and you mentioned that after more than a decade of making video games, you were worried about what they might be doing to kids. Do you still feel the same?

RF: Oh, I have a personal philosophy; it may not be true at all. But I believe that I grew up in a generation where we watched TV. That's all we did, watch TV. And TV was basically 30-minute stories that always had a happy ending. Whatever the problem, in half an hour the problem was worked out.

I'm not being invited to the dance, by the end I'm invited to the dance, right? Or there's a bad guy and by the end of an hour they catch the bad guy. But then there are a lot of people that get divorced and things weren't working out and they leave a job after a month -- no one's patient. They're expecting everything to work out right away because of TV. Now, you think of video games. The message in video games to me is, no matter what you do, you always lose.

Like the whole Space Invaders thing?

RF: Right. You never ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever win. And that I think has created a whole different culture because the kids that grew up playing these games basically have a very fatalistic view: "Yes, what's the point?" I see a lot of it in the music, kind of negatives.

I don't know if that's true or not but there is something there that the experience of playing games is that you very, very, very rarely succeed. And if you drum that into a kid over and over again that's got to be doing something. It's like you never win. Once in a million years you win. Unless you can find the cheat, so what does that teach you?

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like