Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A year ago we relased The Fall of Lazarus. It cost $162.972 and it made $5.155. This is not another postmortem, its a story with letters and numbers, successes and mistakes. If our experience helps somebody, great. Writting it has already helped us.

*This postmortem was originally written in Spanish and posted on GameReport, a spanish video game publication. It’s been translated by myself because we wanted it to be our story, even if our English is not perfect. Sorry in advance!

This is not another postmortem

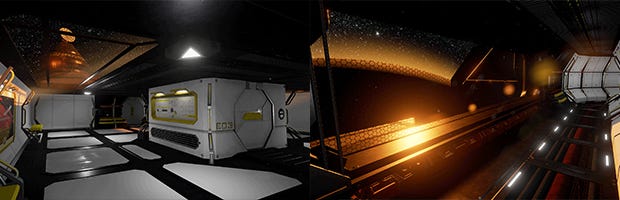

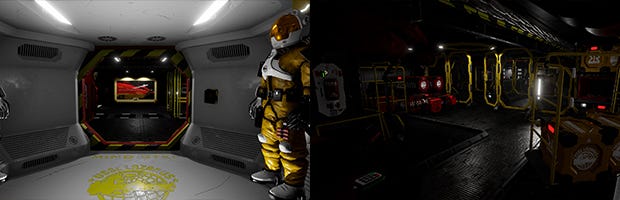

The Fall of Lazarus, a game by No Wand Studios.

This is a true story. The events depicted in this text took place in Zaragoza between 2014 and 2018. Out of convenience for the dead, the names have been left out. At the request of the survivors, the rest has been told exactly as it occurred.

I don’t remember feeling any happiness when we hit the release button. Maybe relief, if there was any. It was late because we wanted the release to be at a convenient hour in the international market. That means we were way out our working hours. Laugh track. It had been a long time since we considered things like that. Noise, sunlight and a soft wind entered through the window. We were only three of us from the whole team working on the game at that time. The rest of the people had already finished, task or interest on the project speaking. We were two programmers and an artist facing the abyss. That day, before releasing The Fall of Lazarus to the world, we were still adding some posters badly translated by ourselves to the spaceship levels or polishing some unavoidable bug. We weren’t working together for the last few weeks: I was sharing a corner of David’s room table and the other programmer was working from his home. At least I was side by side with the man who came up with this all “We are No Wand Studios, an indie video game development studio” thing. The time has come. Our build was validated a few days ago because we always tried to be really cautious. Not enough, but we’ll talk about that later. With one click a year and eight months of work and even more before that would be out for people to use, enjoy or tear apart. Vertigo. Tiredness. Frustration. Enthusiasm?

I don’t remember feeling any happiness when we hit the release button. That sucks, don’t you think? What did we do wrong? Click. Here it goes. May it be the will of the people. We’ve made a fucking video game. Let’s go for a celebration drink to the nearest bar and try to conceal this fear to see how well it does. Fucking laugh, dude! We just fulfilled a dream. Smile at least! Why am I not happy?

JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF THE EARTH

My name is Jonathan Prat, and I’m a storyteller. I studied graphic design, but I also write, draw and design narratives and mechanics for video games. I have no problem speaking in public, I’m not bad managing social networks, I can come up with creative marketing stunts and even editing our own videos. I’m what you could call a one-man band. A jack of all trades. The ultimate indie. And this would be awesome if it wasn’t a lie. An array of good-looking neon titles that illuminate the fraud. Because I’m not making a living out of it. I have a shitty job at a shitty supermarket that allows me to not die trying. My indie dev history, if there is any, starts on 2014, and I didn’t want to be a dev. I didn’t even know I could back in the day. I was fighting with the freelance way of life trying to survive the creative industry jungle. My partner and friend David Bernad is a programmer but there was a sharp producer running through his veins waiting to be awaken. Bureaucracy, planning, scheduling, resources, tasks, drive, focus, resolution. Another array of shallow titles. Almost five years after that toast where we promised to ourselves to make a video game we finally fulfilled that oath. A year ago we released our first video game. And after the storm, a really long lull where nothing happened. And we stared into the abyss. And the abyss stared back at us. How did we get here?

This text is basically a postmortem of The Fall of Lazarus, our first commercial video game, a scifi mystery adventure with exploration and puzzles revolving around themes such as self-overcoming and second chances. But you’ll also see two Windows to peek into. On one hand there is a dirty large window where you’ll learn about the chronicle of a death as foretold as surprising. A tale born as a postmortem fed with our needs that evolved into a sequence of events and numbers more therapeutic than educational. Maybe here you can find something useful, maybe only obviousness. On the other hand there is a skylight filtering the coldest darkness of the raw numbers. If you are interested only in the dark side of this decadent moon you can go right to the ‘Earth Abides’ section and take a peek to the data behind the failure. If you want the whole picture, come with me.

That said, welcome. We are No Wand Studios, or at least we were, and this i sour story.

BRAVE NEW WORLD

The idea of creating a video game development studio was born inside a head but it arose in a bar between beer jars and multicolor lights. I’ve always loved that our convoluted story started from a typical American sitcom scene. “I bet you don’t have the balls to do a video game!” Well, there were balls after all, that’s for sure.

David started our personal funeral march coming up with the idea of making a video game. Our first gatherings were at one of these Irish pub with wooden decoration, soccer streaming and beer taps everywhere. An outlandish idea needed an outlandish place. We sat there the four of us what soon became five planning our path to success in the video game industry. We had it all: two programmers, a writer and an artist. Later we added a fifth one for marketing and management purposes because we knew somebody had to sell our stuff.

The goal was clear: establish the company, have a tech demo of our first video game before march 2015 and blow the roof off of this thing. At that time we were working on a fantasy metroidvania with an art style inspired by Dust: An Elysian Tale, one of those successful indies we looked after with hope in our eyes. That renowned tree that didn’t let us see the burning forest behind it. The story of our game was based on a world and lore developed for years by the former writer of our studio so we had some work done in advance. It was perfect.

We weren’t even getting started and we already had made two mistakes. The first one should had been pretty obvious: none of us knew what we were doing. We were a bunch of enthusiastic professionals in our own fields of expertise but with zero experience in the industry we were about to dive in without hesitation. Some of us just got out of our degrees and some of us still finishing it. Some of us had a slight idea of how video game industry worked, some of us had no clue. But we embrace what we had at hand. If we were to establish a company, invest some money and work our assess off in an uncertain future the only way we had to pull that off was joining forces with acquaintances, am I right? If you ask me now, nope. It’s not the only way. Duh. And secondly there was a problem with the fact that we were living in a country with zero interest on making things easier for starting business. We established our company without having a single line of code written yet hoping we could fund our development working as a consulting and web developing company but running a business here getting into a bureaucracy hell. Do you know that The Place That Sends You Mad sketch from the Twelve Tasks of Asterix? Yeah, exactly. Just like that.

THE FOUNDATION

Our plan needed a company in order to start working for clients so we ended up having monthly payments to do and zero income. In Spain there is a type of enterprise called “cooperativa” that has some benefits for bringing in unemployed workers because it’s based on social economy but in the long term its tedious and not the standard of the business world where limited companies where the usual. When we had to explain to a woman from Valve what kind of company we had, we realized it was not a common thing outside our country. What we didn’t knew at that time was that the process of transforming our company on a limited one was going to take almost a year of bureaucracy and problems from the administration due to the pain in the ass that is the Spanish system. We wanted to go big so we rented an office. Nothing fancy, but another expense to the list. A little space where we could gather and work together. We got it in a centric street of Zaragoza and that was our first contact with the worst kind of entrepreneurship: the rent was paid on cash and at the other end of the wall our landlord tried to deceit a ONG over the phone. But it was what we could afford at the moment with the money we invested for getting the company up and running: $3.427.

Cutting straight to the point, our adventure continued with some creative differences (to put it kindly) with one of the founding partners ended up with him getting out abruptly. Later, we were forced to fire another one of us. Avoiding unnecessary details, it was not worth it. The tension and sadness of those situations were just too much. Even when we knew we were right. Living the dream was not worth none of it.

THE ROAD

We trade two partners noticing a foundational problem: when you establish a cooperativa and get some financial aid due to bringing in partners, you’re forced to keep the number of associates for a long time. And we needed that funding for starting our business, so we had no option but keep being too many people on the studio. We received $5.712 for each unemployed partner who started the company, and we had three of those. We kept generating salaries that no one could possibly charge due to the lack of money but the company needed to keep issuing payrolls in order to be cool with the administration, because if you have a company with people working in it without salaries you’re screwed. It was all legal and well done but far away from optimal.

After those turbulences we moved to a new place, a business incubator for tech companies. It wasn’t specialized in video game companies but we thought we could use its entrepreneur environment and the networking for getting some side jobs and fund our projects. We stopped working on the fantasy metroidvania when the writer who came up with the idea was fired and we started working on a Lovecraftian 2D point and click adventure that didn’t got so far either due to the lack of graphic artist we had on the team. In the meantime, we thought it could be useful to study some video games development and we started looking for some video game focused degree in order to acquire some knowledge and get to know better the industry. We came across a good looking one where they promised experienced teachers with travels to some events and even they gifted you with a laptop. It sounded great but we soon discovered one of the worst problems of video games industry in Spain: the formation bubble. Almost all the teachers had zero experience developing video games and it was a generalist and basic formation without the opportunity of specializing in none of the video game development areas you could possibly be interested on. It was a $7.997 course and it wasn’t worth it at all. It was split in two years: the first year of formation and a second one where we’d do an internship in their own video game development studio, so if you stayed long enough you’d end up paying for working for them! A game studio that we knew later it was filled with students and interns and zero professionals. A couple of months later we got out sick of those practices and we learnt that there was a problem with formation in video games the hard way. We always remember and laugh about that time when we were practicing pitching and the feedback we got from the “head teacher” for a roguelike project we were talking about was “hey, but a game like that would need a lot of variables controlled by code, right?”. We knew later that this kind of fraud it wasn’t at all unusual in Spain. Obviously, there are some great university degrees about video game development, but those are just a few of all of them.

After we got out of there without any kind of experience on the matter but at least we learnt some things about how the industry worked in Spain. We decided to start doing some game jams to get to work with each other and see how we worked together as a team, and we even did a small mobile game that took only a few months to develop and taught us a lot about developing and shipping a game. After that it was time to get serious about making a game, but we had one thing left to sort out before getting at it. The team was closed being four of us because we had to fire one last partner due to two things: we mistakenly thought we needed a certain kind of worker that we didn’t needed after all and the problems that originated. We were partners and workers in our company so we had to guarantee a certain amount of good work and also a great implication in the decisions of the company. Another bitter experience made worse by the fact we were friends with a lot of years on the record. Another stone on that roof that was separating us from madness.

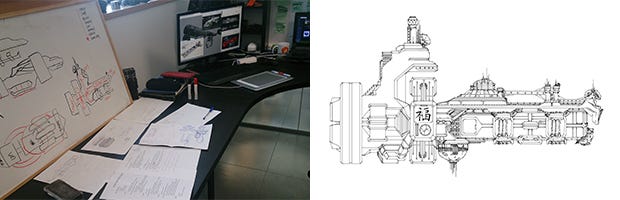

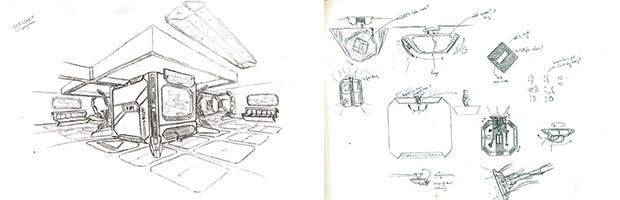

We started working on The Fall of Lazarus officially on October 2th 2017. It was a weak but steady development. We had some unavoidable problems like some crunch times now and then but nothing serious. We were two programmers and an artist so we decided the project needed to be more focused on narrative and gameplay mechanics rather than illustration or 2D work. Also, we had already worked with VR in some serious games thanks to being in a business incubator and the networking we did there so developing an experience with the possibility to make a VR version out of it sounded like a great idea. Nowadays we still think it was de good choice, but maybe with another angle visually speaking.

It walked a pretty standard path I think: we went to some video game focused events like GameLab (Barcelona) or Fun & Serious (Bilbao) in order to get some feedback and we were chosen to be part of Square Enix Collective, their indie supporting platform focused on giving visibility to small projects like our own. We got a 74% of positive rating there so we decided to launch a Kickstarter in order to keep working on our visibility and get some extra funding for the outsourcing work we’d had to face to finish our project and it was a moderate success: we asked for $9700 and we raised $11.195. We knew our game was a niche oriented one and it was not going to get a lot of attention so we aimed for a realistic and humble amount of money because we thought it was better to succeed in a crowfunding campaign rather than having to cancel it. You need to know one thing: absolutely all crowdfunding need to have some of the funding already secured before launching the campaign. It can be family money, your savings or whatever you want it to be, but data says that you need around the 30% of what you’re asking for already secured in the first days of campaign if you want to pull it off. We had it but even with that we needed our campaign to be retweeted by Rami Ismail and Paul Kilduff-Taylor in order to get it to the finish line. The game was funded by 326 backers and viable: we had what we needed in order to finish it.

We launched a prototype of the game that would also serve as a prologue story titled The Fall of Lazarus: The First Passenger on June 2017 receiving good feedback and boosting us on our idea of making this game. This vertical slice was playable for the first time ever at GameLab 2017 and we forced ourselves to accomplish that deadline: we needed to introduce ourselves to the video game world in one of the most important events on Spain. This meant that we poured into the game more hours than we should, reaching the absurd number of 46 hours without sleeping and being forced to work on the train in our way to Barcelona while another one of us was doing the same in our office in Zaragoza. Even when we were at our stand, David had to patch a nasty bug out of the build coding while sitting on the stairs of the main floor while I was managing the stand where curious people started playing our space adventure.

And then, darkness. We got into the dev cave. An endless amount of hours working on an ever changing project. I remember, as an example, that time I proposed we should change the genre of our protagonist. We were working with a male lead but after a weekend of thinking I thought I wasn’t okay with how the things the protagonist had to overcome affected him as a man and the message that would send to a society struggling with diversity problems. The fact that it could be easily fixed because we hadn’t recorded any line of voice over yet was key on making this decision. In the end this decision brought hate from some players that didn’t like a female protagonist in our videogame saying that its voice was “irritating”. The fact is that the actress that worked with us is Katherine Kingsley and its one heck of a professional that has worked on big titles such us Vampys or We Happy Few.

Our first video game came out on October 2017 and well, as they say, the rest is history.

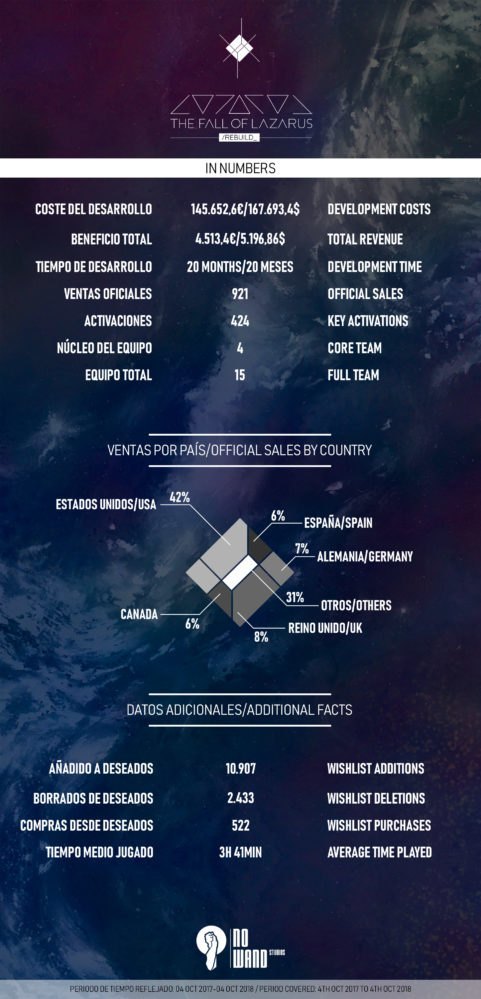

EARTH ABIDES

If you are here is because you’ve learnt about our story or because you missed it on purpose looking for the numbers, so here we go: it took twenty months to develop The Fall of Lazarus with a virtual budget of 166.717$. I said virtual because salaries are part of it but the studio owners collected none of them. From that Budget, 65.075$ were paid for real. More than 20.000$ went to paying taxes, fees and all the things spanish government makes you pay when you have a company set up here. I kid you not, it’s insane. A year after its release, we’ve earnt roughly 5.166$. 921 copies sold on Steam. 424 key activations where we are counting those that went to our backers, press people, events and that kind of stuff. Summarizing: a failed project that makes impossible to keep developing our second video game the way we were doing it until now. You can take a look to the infographic with more relevant data and curious facts about the business of the century.

If you are here is because you’ve learnt about our story or because you missed it on purpose looking for the numbers, so here we go: it took twenty months to develop The Fall of Lazarus with a virtual budget of 166.717$. I said virtual because salaries are part of it but the studio owners collected none of them. From that Budget, 65.075$ were paid for real. More than 20.000$ went to paying taxes, fees and all the things spanish government makes you pay when you have a company set up here. I kid you not, it’s insane. A year after its release, we’ve earnt roughly 5.166$. 921 copies sold on Steam. 424 key activations where we are counting those that went to our backers, press people, events and that kind of stuff. Summarizing: a failed project that makes impossible to keep developing our second video game the way we were doing it until now. You can take a look to the infographic with more relevant data and curious facts about the business of the century.

I have to admit we took inspiration from the lovely and useful infographics that ustwo games made for their Monument Valley postmortems so you can imagine how humiliating was to compare data and numbers with such a great success. But that is what this is all about: putting perspective to this industry. Looking back, I think we can point out without doubt what we did right and what we did wrong and what we can learn from each decision. So, at least using the classic postmortem structure, let’s go with the bullet points:

WHAT WENT WRONG

Spain Is Different. As I told you before, we established our company too early. Sadly in Spain there is no system that allows entrepreneurs to minimize the costs of having a company legally established if you have no income. It’s irrelevant if you’re starting a small start-up or running a years old bar. This becomes a wound that never stops bleeding. Month by month. If you reduce your activity to the minimum and only rent a tiny office being two of us in the company you’ll be throwing away 1.200$ per month in a daily basis. And if you have a secondary job that allows you to try to become a dev maybe you’ll have to face some troubles filing your federal taxes due to having two salaries (although you’re not receiving one of them because is your company and you have no money but you have to have salaries to do things right legally speaking). And believe when I say that bureaucracy in Spain is a pain in the ass. It’s old fashioned, slow and painfully clumsy. If you have a company here, you’ll spend a lot of money and time going forth and back for everything.

Too Fast & Too Furious. We assembled a team too big and unexperienced not only in the video game sector but in any of them. We knew each other (some of us were even friends) but we had never worked together before that. This had two outcomes: we’d be a perfect dev machine full of lovely people or a disaster of personal proportions where realities and negative aspects of each one of us create a flimsy house of cards.

Formation bubble. If here in Spain we are experts on something it’s on creating bubbles. We are masters of seeing an opportunity, exploiting it to the limit and blowing things up leaving a wasteland full of dreams behind. Video games formation is one of them. You only need to take a look at how many university masters and degrees. A lot of generalist courses with professionals from other areas non-video game related with basic knowledge about the medium taking in thousands of excited youngsters with promises about creating their own video game. We’ve been offered to do some talks and even be teachers in an online degree when we hadn’t released our game yet.

Keep It Simple, Stupid! Obviously, we fell in the most typical error: we underestimated the work we’d had to do to finish the project. What were born as a game set up in an unipersonal spaceship with a mystery and a bunch of puzzles became an experience with the scope of ‘Firewatch’ without a team of experienced ex-triple A devs behind it. This ended in a really hard development. Why did we not invest more time then? Well, that’s an easy one: because there was no more money.

Keep It Simple, Stupid! Obviously, we fell in the most typical error: we underestimated the work we’d had to do to finish the project. What were born as a game set up in an unipersonal spaceship with a mystery and a bunch of puzzles became an experience with the scope of ‘Firewatch’ without a team of experienced ex-triple A devs behind it. This ended in a really hard development. Why did we not invest more time then? Well, that’s an easy one: because there was no more money.

It’s the market, my friend! We began working in our space adventure on 2016. Firewatch was rocketing for the one million sales, Gone Home kept standing at the front of the vanguard indie games and Moon was already a masterpiece and cult movie for scifi lovers. But when we finished the development on October 2017 only one of those things survived. People got tired of walking simulators at the same time that term became standard and the independent scene got saturated. And Steam, well.. you know the drill. If you get there, be sure to go vaccinated.

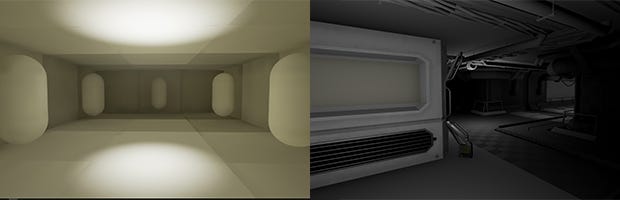

Next gen! 4k! HDR! When preproducing The Fall of Lazarus we abandoned but not forgot the idea of making it a virtual reality game. It was perfect for that kind of experience. This added up to the fact that we want to work with an oppressive atmosphere looking for a realism we thought would fit better with the script we were working on resulted on hyper realistic visuals. The hyper realism we could afford at least. What I thought it was a visual style that should bring to mind things like Alien ended up being a poor and plain artistic direction that turned our game invisible on the market. Hyper realism needs a big budget or you’ll get something just fine. And fine isn’t enough. An obvious error I’ll personally never forgive myself for.

If you don’t have a bug, you have two problems. You have a bug and you don’t know which one. It was economically impossible to test our game before launching it. Of course, we tested it ourselves during development and our puzzle designer did some walkthroughs looking for problems but that clearly wasn’t enough. A good game need good testing, and testers cost money. Testers are an essential role on game development and we became very aware of that when users started experimenting weird bugs and stuff in their runs.

The Mystery Box. We did an exploration and puzzle game where the bigger puzzle was the mystery. All the narrative revolves around the idea of the player living what the protagonist lives and gathering the info provided with the main story and the environmental storytelling players should be able to unravel the mystery. But there is no plot twist. We don’t have Morgan Freeman coming up explaining to you what the hell is going on. That was up to the player. And what we thought (and we’re still proud of it) it was a total confidence in the player and a puzzle for them became a handicap on reaching the niche market we were aiming for, the kind of player that enjoys a twisted narrative with a challenge beyond the obvious. The game closes up with an almost anticlimactic ending that has its meaning on the bigger narrative scheme but if you aren’t into it hard enough you can end up really frustrated.

The Mystery Box. We did an exploration and puzzle game where the bigger puzzle was the mystery. All the narrative revolves around the idea of the player living what the protagonist lives and gathering the info provided with the main story and the environmental storytelling players should be able to unravel the mystery. But there is no plot twist. We don’t have Morgan Freeman coming up explaining to you what the hell is going on. That was up to the player. And what we thought (and we’re still proud of it) it was a total confidence in the player and a puzzle for them became a handicap on reaching the niche market we were aiming for, the kind of player that enjoys a twisted narrative with a challenge beyond the obvious. The game closes up with an almost anticlimactic ending that has its meaning on the bigger narrative scheme but if you aren’t into it hard enough you can end up really frustrated.

Indiecalypse. There is one? There isn’t? It doesn’t matter. What we’ve surely lived on our own and dev friend’s experiences is that there is no investment whatsoever. Maybe a little bit, yeah, but it’s really hard to get it and even harder in our country. Foreign investors tend to invest on their own countries in order to get tax benefits, video games are a risk market with a long-term return or maybe you are an unexperienced rookie. Pick your poison, but the money ain’t coming easy. We had to hear things like “this is not a Call of Duty, how do you plan to sell it then?” while trying to sell our project to some investors. We have a friend that has faced more than twenty “no” having a great portfolio. Yeah, generally speaking, it’s as bad as it sounds. There will be a lot of people saying that “money is just right there, you just have to go with a good project and take it” but it’s not that simple.

Steam’s monopoly. When we started our project we got one thing right: the game was going to be published in all the platforms available. In our first year at Gamelab (Barcelona) Rami Ismail give an awesome talk titled WRONG speaking about all the more than probable mistakes an aspiring indie dev can make while trying to make a living out of it. We made a lot of those but we learnt at that talk that we should try to get our game on every distribution platform available for us. We did it and it worked! Gamejolt in particular was really great for us. Our project demo was on the home page for some time and it reached one of the highest number of followers for a project. Even the updates had a good reach. But the surprise came when we finally released our game. 14.99$ seemed like too much for a community based on free games and youtubers looking for funny material. If you go right now to The Fall of Lazarus Gamejolt page you’ll se this comment: “I would love to play the full game but not at that price, its just not worth it. (…) I would advise no more than $3 and focus on number sales.” Knowing the numbers, the work and the story behind the creation of a video game… what can you answer to that?

WHAT WENT RIGHT

We do it fucking right. This was always one of our mantras. A simple but functional one. From day one we knew we had to write every decision down and sign it. Private contracts, outsourced work payed via closed budget and not generate any external debt. We were not going to fed on interns or trainees and we didn’t want to teach on degrees without having any experience in the matter only because we had a company and a website. We believe internships are a great way of knowing the industry you are going to work in but you need to end up in viable company with experience and professionals. We didn’t want to build up our studio based on the work of students passing by our office without paying anything for their work. This is a common practice in our country and we’d had to hear people being surprised by us not wanting this for our studio and that was a hint of how messed up video games industry is in Spain, so we decide to not take that path. Maybe we did wrong because, let’s face it, we made it easy for depression and anxiety with the fact that everyone outside our company who worked in our game was payed accordingly and the core team of the project haven’t seen a penny. But this also has allowed us to have a healthy company with zero debt with banks. All that is left to pay its ruled by contracts with conditions signed by the people who was partner of the enterprise. Former partners have received their cut of the money they invested on the project when they stepped in and was theirs by right when they left.

Game Jams. Before entering dev cave mode, we did some tiny games and a mobile project. This let us work as a team and experience in our flesh the whole process of creating and shipping a video game. We also learnt the tools and software needed to do so. Those are pretty bad games, some of them particularly ugly looking, but it was a logical step and we earn a lot of valuable experience.

The First Passenger. The idea of a vertical slice doesn’t work well with narrative driven video games. In order to make it work, we needed to cut from the main story one of the most shocking moments of the script and develop it without its context and pacing so we had to come up with a better idea for selling our game without spoiling it. How could we create a noticeable chunk of our game without compromising its pacing and our workflow? We needed to show our gameplay mechanics and visuals even if it was a pretty standard first-person exploration and puzzle game and also a sneak peek of the narrative we were working on, our true selling point. We did some thinking and finally I came up with an idea: to develop a short story set in the same universe sharing visuals, game mechanics and narrative. This could work as a demo and also as a prologue of the main story being a conclusive script with its own protagonist and goals. The player interested in our game would be able to try it and be satisfied with a closed story designed to work on its own. The perfect plan. And it worked pretty well! We thought our prologue was ten to fifteen minutes long but in the end, it was almost a half an hour worth of gameplay. We saw things we liked for the main game and other things were scrapped out and that testing and feedback was very valuable to us, something we weren’t able to get with a conventional vertical slice. And we also had extra content to ship with the main game, a prologue that added up some layers to the mystery and narrative of the full story.

Crowdfunding. While conceptualizing The Fall of Lazarus we realized we were going to need some extra investment to cover some fundamental things of the development like music, sound design, translation and the most important of them: voice over. The minimum required to able to finish the project. We did the math and we needed $14.850. If we were going to outsource it we wanted to work with trusted professionals. We’d hire Sonotrigger, a company used to work in video game music and sound design from Valencia and we also wanted to work with Localise.me, a bunch of translators who had work in some great games such as Divinity: Original Sin. We contacted SIDE for the voice over, a British company renowned in the games industry. All of them did an outstanding work in The Fall of Lazarus. The campaign was successful and the game was delivered on time, fulfilling the promises we made to our backers.

The Mystery Box. Warning: massive spoilers of The Fall of Lazarus plot even for those who have already played it. Okay, now you’re advised, let me explain why I’m talking about The Mystery Box in both Right and Wrong sections. It’s simple: we told the story we wanted to tell. Our narrative revolves around an abused woman in a dystopian future where she’s suffering post traumatic stress and ends up killing her husband in order to survive. This pushes her to the edge of madness and decides to get help from a neurohacker who builds up a simulation where she can go through her duel and rewrite her memory to be able to be at peace with her life and move on. It’s a brutal story about gender abuse trying to awake player’s consciences but also a story about strength, self over coming and second chances. This simulated memory reconstruction therapy is what players experience while playing The Fall of Lazarus from start to finish, without cuts or cinematics, and that’s the final mystery to unravel. The missing piece. The few people who uncovered all of this were blown away by our story, and that’s really satisfying for us. Mission accomplished.

The Fall of Lazarus available on Steam, Itch.io and Humble Store. The game exists, it’s finished and you can buy and play it if nothing weird happens without inconvenience. It’s a video game and it’s done. Maybe you could think that finishing the development of a game is no success because, well, it’s our job. We thought that too for some time. But when you look around and see how many developers struggle to ship their creations and day by day studios keep getting closed and a lot of teams vanished without notice you start to change your mind about this and assess the value or shipping a game. It’s not a consolation prize, it’s a life goal accomplished.

ENDER’S GAME

After the release there was only silence. Some of our former partners didn’t reached back never again and that took a toll on us. That added up to the fact that, you guessed right, the launch was a commercial disaster. We didn’t got visibility on press and the game was buried on the digital markets before it could get a chance. And we knew that once it was deep down the video game market, there was almost zero possibility of bringing it back to life. We received a few reviews and some of them enthusiastic. A couple came from friends and relatives, so you always have that feeling of distrust about them. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. The worst reviews teared us apart. We tried to hide it and convince ourselves that the world is full of haters not worthy of our time. A few of those were just that indeed. Rude comments from people without any interest on our game at all. But there were also reviews full of good points and clever reasoning and those were even educational. We were able to fix some bugs with that feedback, but with the pass of time it was getting harder to move our game. Steam’s algorithm didn’t have enough data about our traffic to decide our game was worthy of putting it on the front page or showing it to people who might be interested in that kind of experience and that was it. Visibility, the great villain.

After the clearing of the wreck, we decided to work a little bit more on improving to the maximum the game and closing it for good. Named The Fall of Lazarus /Rebuild_, we published the last patch polishing all the bugs we could and some problems we got to know with the feedback of our players. And, after that, we started working on a new thing: Hello, My Name Is Nobody. This game is still on development because we think we have something special on the works but we will not develop it the same way we did before. This is how this works: we applied for a government financial grant with this new project. Some weeks ago, we discovered we were one of the three video game projects they chose to be funded. We needed $57.137 and they assigned to us $22.848. Thanks to this we won’t have to close the company for now until we fulfil our duties with this economic aid, justifying costs and everything. For your information, that money is already gone in things such as a first batch of 3D asset ($1713 to a local visual effect company named Rush VFX), another $500 for a freelance 3D generalist for some extra assets and the payment of $1000 on the Google suite, hosting expenses and software licenses. If you do the math, you’ll see it’s not a great deal and you can’t live from this kind of grants. The project is still alive for those who might think “well, at least they’ll get some money, they earnt it” you are sadly wrong. In this kind of grant you can only assign a 20% of the funding to workers salaries so, in our case, that’s only $2850 each at most. That makes like three months of living like a normal person. Yay! Writing all of this is going to kill me…

On July of this year, the inevitable just happened: my partner David was diagnosed with depression and its probable that I had something similar myself, but I got lucky and I went that far with my anxiety problems. At least until last august and September where all of this hit me the hard way and went through one of the worst times of my live. And when we hit rock we realized our experience was all a lie. Our office, our game, the events, the sales. Being developers was also a lie. Kids pretending to be adults. Two toddlers with a trench coat. We assessed our experience, ups and downs, successes and mistakes. It wasn’t all that bad! But when we realized that we were already unconscious lying on that beach we worked so hard to reach. It was time to sit and take a deep breath. Take our time and step aside. And convince ourselves that maybe all of those lies weren’t for nothing after all and we had in fact learnt something. We had experience, knowledge and even more passion. Because we managed to at least don’t lose our passion in all those mistakes and hard times. It was time for us to heal.

THE TIME MACHINE

The idea behind this text was born from the concept of a postmortem, the need of a PR stunt that maybe brought some attention and the anxiety for opening up and talk about our difficult experience. When we were working on this postmortem, we realized the last one was the most important of them all, and we had to finish and publish it no matter what. It is our therapy. Because we don’t know where we’ll go next. What is going to happen to No Wand Studios, the company we’ve been fighting restless for five years. A studio, a Brand, a logo, a project, an experience, the memories and a product that now we hate viscerally and irrationally. And that’s unfair. While thinking about this postmortem I realized of something terrible: I was totally afraid of looking the Steam page of our own video game. I wasn’t able to get there because maybe there was some new review tearing apart our hard work without compassion. So maybe all this writing wasn’t for you but for us. I don’t know. If there is one person that finds something of all of this useful, that’s fine by us. It was worth it overcoming the pain of facing our own failure. We’ll keep trying. As Ojiro Fumoto once said, «it only takes one player to justify the existence of a game». Now we know that. We’ve seen it in the faces of the people playing our games at our beautiful EGX stand. We’ve felt it in their smile while finishing our demo. We Will forever treasure it on that moment when Goichi Suda yelled «Sugoi!» at our stand and later he took a picture with us. We only need to find our way. A viable way.

We truly believe there is a way. We can fix this industry. Rookies like us can be better and learn from each other. And for that to happen we thought it was necessary not only telling our story, but also bring out the numbers. Because successful stories are interesting and motivational but failures are likely the ones where you can learn the most from. And in an industry really opaque like this one, we think people have to start talking about numbers, mental illness and the real cost for developing a not-so-successful video game. The real cost.

I don’t know if there are too many indies out there, or if we’d have to stop encouraging young and unexperienced developers. But I do believe there is a ruthless market and a massive amount of games out there reducing your success probabilities. There is a formation bubble and depending on where you live you’ll have to face the problems of your own country in this turbulent world ruled by mad men. At least we know what we want to do. We want to make fucking video games. I think there isn’t an only way of surviving this industry and its key learning from everyone, adapt those lessons to our own situation and take nothing from granted.

To the people we’ve met along the way or have been with us in our journey, thank you for the warmth. To the people who didn’t came along, thank you for your manners. And for the rest of you, thank you for nothing, I guess. See you in another life, brotha.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like