Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Persuasive Games co-founder Ian Bogost uses the classic board game Monopoly to illustrate how game designers can use established brands to their advantage for in-game advertising, in this in-depth Gamasutra feature.

Monopoly has a long, complex, and generally unknown history. Perhaps the most surprising historical curiosity about this classic game about being a real estate tycoon is that it was originally created with an entirely different set of values in mind.

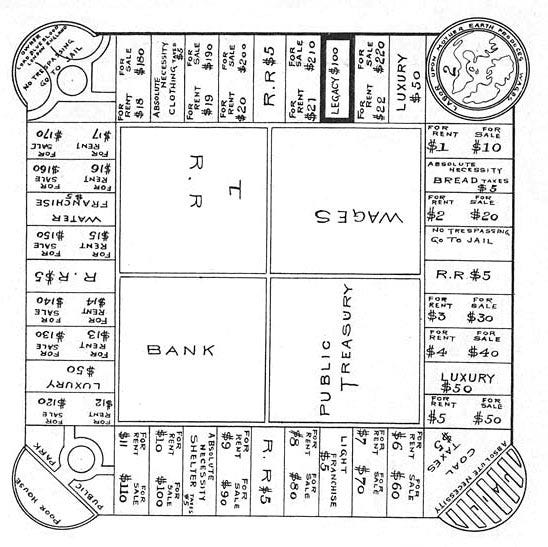

In 1903, thirty years before the initial release of Monopoly as we know it, Elizabeth Magie Phillips designed The Landlord’s Game, a board game that aimed to teach and promote Georgism, an economic philosophy that claims land cannot be owned, but belongs to everyone equally. Henry George, after whom the philosophy is named, was a 19th century political economist who argued that industrial and real estate monopolists profit unjustly from both land appreciation and rising rents. To remedy this problem, he proposed a “single tax” on landowners.

The Landlord’s Game was intended to demonstrate how easy it is for property owners to inflict financial ruin on tenants. As a learning game and a game with a message, the title begins to look a lot like a serious game. Even if Monopoly was created to celebrate rather than lament land monopolies, the game does demonstrate the landlord’s power, for better or worse.1

FIGURE 1: Original 1903 game board for The Landlord’s Game

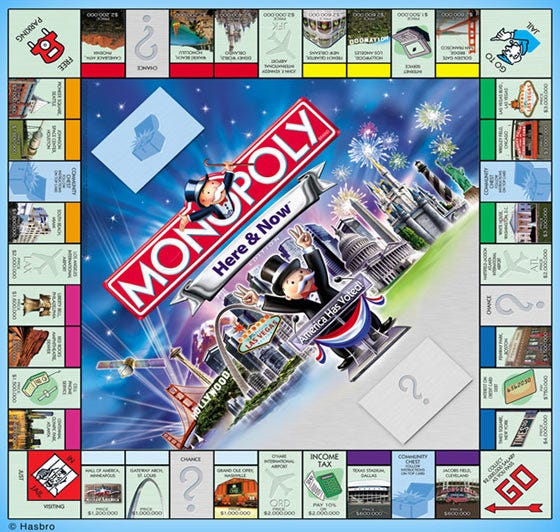

But recently this famous game has associated itself with another side of industrial capitalism: advertising. In 2006 Hasbro released a version of Monopoly called Monopoly Here & Now. This edition updates a number of things about the classic 1930s version of the game, including changing the properties to more widely recognizable ones: Boardwalk becomes Times Square, Park Place becomes Fenway Park.2 Instead of paying luxury tax, the player shells out for credit card debt. Cell phone services depose the electric company. Airports replace railways. And in Here & Now, you collect $2 million for passing Go. Times have changed.

FIGURE 2: Monopoly Here & Now game board

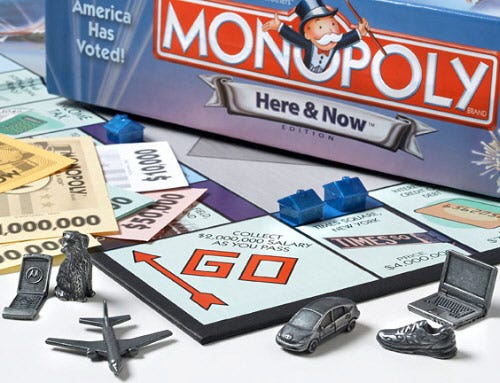

Renaming properties on a Monopoly board is certainly nothing new; dozens of official and unofficial “affinity” editions of the game have been created, one for every city, town, college, TV show, and pastime imaginable (there’s even a NASCAR Monopoly). But Here & Now also replaces the classic game tokens with new, branded tokens. No more thimble, no more car to argue over. Now you have a Toyota Prius, McDonald's French Fries, a New Balance Running Shoe, a Starbucks Coffee mug, and a Motorla Razr phone. In addition, there's a generic unbranded laptop, airplane and dog.

FIGURE 3: Monopoly’s new branded game tokens

In his recent book Monopoly: The World’s Most Famous Game, Philip Orbanesdetails multiple versions of the game’s early retail edition.3 The game’s familiar metal tokens had been modeled after charm bracelets, but they added to the game’s cost. During the depression entertainment was a luxury, and Parker Bros. also offered a less fancy version that left out the tokens to lower the product's cost. Players provided their own game tokens, often scrounging for objects of the right size and heft to use on the board. The game pieces we take for granted thus represent important aspects both of the game's historical origin (charm bracelets of the 1930s) and of its history (the financial pressures that motivated the lower-cost edition).

Normally we might dismiss Hasbro's move as deliberately opportunistic and destructive. After all, Monopoly's branded tokens seem very similar to static in-game advertising (like the Honda Element that on the snowboard courses in SSX3). In a New York Times article about the new edition, the executive director of a consumer nonprofit did just that, calling the new edition “a giant advertisement” and criticizing Hasbro for taking “this low road.”4

But perhaps the historical relationship between the tokens and the game’s cultural origins should dampen our reaction to the little metal fries and hybrid cars. None of the brands solicited the advertising nor paid a placement fee for it. Instead, Hasbro itself solicited those particular brands to appear in the game. Hasbro Senior Vice President Mark Blecher claimed that the branded tokens offer “a representation of America in the 21st century.” The company, argues Blecher, brings the “iconography” of commercial products to the game of Monopoly.

Blecher is a marketing executive, so we should think twice before understanding his justifications as wholesome design values. Certainly other advertising-free design choices would have been possible. The game’s original tokens were similar in size and shape to bracelet charms—perhaps a more appropriate contemporary update of small tokens would have been SD memory cards or Bluetooth earpieces.

But Blecher has a point: for better or worse, branded products hold tremendous cultural currency. They are the trifles, the collectibles that most of the contemporary populace uses to accessorize their lives. Here & Now uses branded tokens to define its game world as that of contemporary corporate culture, in contrast to the developer baron world of the original game.

1. Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman also discuss the differences between the two games in their text on game design, Rules of Play (MIT Press: 2004)

2. The new properties were decided by popular vote of the general public; according to Hasbro, over 3 million online votes were tallied.

3. Philip Orbanes, Monopoly: The World’s Most Famous Game and How it Got That Way (New York: Da Capo, 2006).

4. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/12/business/media/12adco.html

What lessons can we learn from Monopoly Here & Now that might apply to advertising in commercial videogames? Most developers are concerned with the appropriateness of brands in games, and even large publishers have shown their unwillingness to hock in-game space even at high premiums—EA canceled their plans to sell brand placement in The Sims 2 after their failed experiments with Intel and McDonald’s in The Sims Online.

Yet some developers and players also believe that branding is appropriate when it enhances realism in a game. This principle is usually cited in reference to urban and sports environments, which are littered with advertising in the real world.

In this case, realism means visual authenticity—correct appearances. But Monopoly Here & Now doesn’t include brands for the sake of appearance—just about any icon would have looked fine. Instead, it includes the brands to add contemporary social values to the game.

In addition to promotion, in-game ads and product placements also have the potential to carry the cultural payload of the brands that mark them. Such inclusion signals a design strategy different from visual authenticity—after all, it doesn’t really matter much whether billboards and sports arenas carry real ads or fake ones. Instead, brands might be used in the service of the authenticity of practice. Brands are built around values, aspirations, experiences, history, and ideas. Consumers make associations with brands when both are put together in particular contexts.

We might lament the prominence of material consumption in culture, but that prominence is also undeniable. No matter one’s opinion, games have not yet made much use of branding as a cultural concept.

I tried to use branding for social commentary in Disaffected,a videogame critique of the Kinko’s copy store that uses the chain’s brand reputation for rotten customer service in a satirical commentary. And Mollendistria’s McDonald’s Videogame uses that company’s brand reputation for massive worldwide industrialization to expose the social dangers of global fast-food. The branding in these games is unauthorized; the games critique rather than promote these companies; I’ve suggested the name anti-advergames for this type of social critique.5

FIGURE 4: Unauthorized branding in Disaffected! and The McDonald’s Videogame

Of course, unauthorized brand abuse in large commercial games might not be possible or desirable. But brands’ cultural values can still be used as a bridge between visual appearance and game mechanics. In some cases, it might be easier for a player to understand the behavior of a character, situation, or idea when aspects of that behavior can be offloaded from the simulation into a branded product or service.

Think of it this way: what can you infer about a person who drives a Mitsubishi Lancer, or wears Manolo Blahnik shoes? Arguably, this strategy used to be the primary way brands made their way into games. In Gran Turismo or Flight Simulator, specific brands of vehicles contribute to players’ expectations when they get behind the wheel or the yoke.

This doesn’t apply only to “lovemarks,” the name ad executive Kevin Roberts has given to brands people grow to love rather than just recognize (Apple, Starbucks, LEGO are examples).6 It also applies to less desirable brands that still convey social values—think of Edsel, Betamax, or Pan Am. Historical brands that have passed their prime still carry extremely complicated cultural currency. What comes to mind when you think of L.A. Gear, Hypercolor, or Ocean Pacific?

If we think of brands as markers for complex social behavior, we can also imagine recombining brands’ encapsulated social values in new contexts: the Yugo stagecoach; the Preparation H-needing blood elf. These are perhaps silly examples—and some developers might fear that they represent in-game advertising’s worst threat: advertising’s colonization of even the most incompatible games. But like the creators of Monopoly Here & Now, game designers should recognize that there might be times when advertising could actually enhance a design, not just take away from it.

You can use advertising to exploit cultural preconceptions about known items that then serve as a kind of shorthand for aspects of your game world. And that sort of attitude turns the tables on in-game advertisers, making advertising a tool in the hands of the designer, rather than one in the hands of the brand, agency, or network.

5. See Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).

6. Kevin Roberts, Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands (NY: Power House Books, 2005). For a collection of lovemarks, visit Robert’s companion website at http://www.lovemarks.com.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like