Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The chief creative officer of independent triple-A developer Ninja Theory (Enslaved, DmC) discusses how he believes storytelling is an integral part of the medium and how it should evolve, and what changes in the market bring to the games business.

[The chief creative officer of independent triple-A developer Ninja Theory (Enslaved, DmC) discusses how he believes storytelling is an integral part of the medium and how it should evolve, and what changes in the market bring to the games business.]

There's a lot of discussion about whether or not storytelling is a valid part of the medium. But accept, for a moment, that it's a big part of triple-A games. How should it evolve?

Having tackled cinematic projects like Heavenly Sword, Enslaved -- with 28 Days Later writer Alex Garland -- and now the Devil May Cry reboot DmC for Capcom, Tameem Antoniades is in a position to know. As chief creative officer at UK-based game developer Ninja Theory, he has been working to evolve his cinematic skills -- to understand how a story can fuse with gameplay to create a holistic experience.

In this extensive interview, Antoniades discusses this from both a philosophical and practical perspective, diving into process as well as headier questions. And he also discusses what it means to be an independent studio making triple-A games, why Enslaved may not have sold as well as it could have, and how digital distribution will break open the creativity of all games, from small to giant.

You got a lot of acclaim for Enslaved. But I guess it sort of kept coming up again and again as a game that didn't sell as well as [publisher] Namco Bandai had been hoping. What do you think?

Tameem Antoniades: I think it's always a difficult equation, isn't it? It's like it's not enough to just make a game. All the ducks have to be lined up, and those ducks include the creative ducks, like the theme and the content. I wonder whether Enslaved was a bit too fantasy, or off the mainstream fantasy, on one hand.

But it needed support, it needed a drive, a big push, and I don't think it necessarily got that. I really kind of hate it when people make, say, "Oh, marketing didn't support it," but a new IP needs to be visible, and I didn't feel like it was. A lot of people still even haven't heard of the game.

I've been seeing that a lot lately. Some publishers are not seemingly totally comfortable; they don't seem to be pushing these new IPs. The publishers get these made and then -- to a greater or lesser extent -- they don't seem to really move the needle.

TA: From our point of view as a developer, I'm always puzzled by it. Why bet on triple-A if you're not going to spend for triple-A? You can't have it both ways. But, you know, I think we're proud as a team that we've got the game done, we got it on time. We thought that we did our job.

It sounds like you're really influenced by working with [28 Days Later writer] Alex Garland, over the course of that project, in terms of how you moved into your creative decisions moving forward.

TA: Yeah, that's absolutely true. Alex is a gamer, a big gamer, always has been, and he's very curious as to whether his skills as a filmmaker would translate into games. And he was looking for an opportunity for years to work in games, and hadn't really found one until I begged him to go on board and gave him the keys to the kingdom.

He spent the best part of two years in the office working with our designers and with me, so he got stuck in. And he used his dramatic eye when reviewing not just cutscenes, but the levels. And as game developers, we don't always have that dramatic eye. We're not used to the language of film, which is cameras, body language, lighting; those things tell stories more than the dialogue in film.

So watching him, observing him, how he does that, it's something I took on board, and I'm a bit of an evangelist for that now. Like storytelling visually, creating drama visually in games.

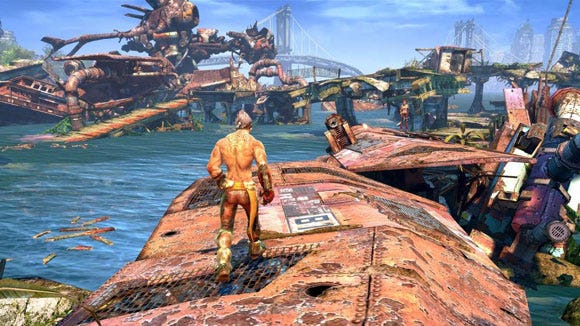

Enslaved: Odyssey to the West

Well, it's a very visual medium, and now we've reached this point with the fidelity that we can achieve in this current generation. If you look at some of the more creatively successful games, they really embrace that visual storytelling.

TA: Yes, I agree. Things like Ico and those stable of games do it purely visually, to an extent. And BioShock.

BioShock's a good example. You've mentioned that sometimes story is not really seen as an important component of games. But I think when you say that, you mean linear narrative, not necessarily story, right? Because there's more to storytelling.

TA: Like any medium, I think there is actually elitism. There's an elite few that do actually believe that stories have no place in games. That it wasn't about that at the beginning, and it shouldn't be about that now. But I don't think they're wrong. I think the games platforms are evolving, and the fidelity's allowing for stories, and those stories can be linear and they can be branching. They're different types of storytelling, and I think there's room for all of it.

You've definitely got a cinematic bent, right? Starting with Heavenly Sword and moving forward it seems like you've embraced cinematic storytelling.

TA: Yeah.

But I get the sense that you want to try and integrate these techniques more fully into the games, and not do the typical cutscene/gameplay/cutscene/gameplay.

TA: I think I would love to explore the possibility of branching stories. I mean, it's not so much branching stories that I think is the key to interactive narrative as it is characters that change. So it's the characters that define it; the plot is much less important than the character journey.

And having characters that can change throughout an experience, and actions that you do against someone, or in the presence of someone, will change how they think of you later, and how they behave around you later, I think, is ripe for exploration.

The difficulty is that it's not just about narrative. Storytelling is about the camera, the lighting, the body language. So when you're trying to tell a branching story, you have to consider all those elements. I can make the viewer feel uncomfortable by moving the camera, putting it in a slightly awkward angle, focusing on details that make you feel uncomfortable. This language needs to somehow be integrated into interactive storytelling.

When you're talking about characters evolving the story, have you given a thought to doing that interactively? Or are you speaking of purely in terms of writing and a character arc in a more traditional way?

TA: I don't know, I mean, to be honest, I haven't been deep into that. It's something I've been talking to Alex a lot about, but we haven't embarked that project, to encompass that yet. It's something I'd love to do.

When I talked to you when you were doing Enslaved, you said that was right when you just became a two project studio, right? And obviously you have Devil May Cry going. Do you have another project going?

TA: Actually, we were hoping that it would be the Enslaved sequel... I wouldn't say it's not happening -- because you never say never -- but it's not started. We're not progressing on that. So for now we're going to focus on Devil May Cry. Everyone's full attention is on that game, and we've got one eye looking to the future on our second project, which we will need to start in the next few months.

A lot of studios have faced that challenge. You've seen a tremendous amount of independent studio closures and or layoffs and downsizing. Is that something you've been concerned with?

TA: Yeah. As an independent studio, it's said many times, but you're only as strong as your team. And our team is a family -- they have been together for years; our first employee is still with us. And people like our studio -- we don't have a big turnover, we treat our staff well, we don't work overtime, and if we do we give time off in lieu.

It's important for us to not burn out our team, and because of that we have a loyalty. So it's important that we keep that team together and we build on it. And to a larger extent, what we do is defined by our team. So I think we're a strong studio with a good reputation and we can do projects; it's more a matter of which projects we choose to do. So I'm hoping we'll get to that.

Something you said earlier that intrigued me was the idea that maybe Enslaved wasn't mainstream enough. To get a triple-A game to sell in the market, how mainstream does it have to be?

TA: It's difficult, because what defines mainstream? Because when you look at other mediums, like the biggest films of last year include The King's Speech and Black Swan, which are the equivalent of an indie game. You know, they're fairly low budget, they're not about warfare or sports; they're not a trope, in the classic sense.

So it seems like Hollywood's got much more diversity than the games industry has. And I don't know exactly why this is, but I suspect it's the publishing, retail model of 40 pounds, 50, 60 bucks a game doesn't allow players to take chances with their money; it doesn't allow publishers or developers to take risks. And the only way you can be sure to sell to someone is to sell them something familiar.

I actually think that theory is completely wrong -- I think that ultimately innovation does sell, and messaging is needed. But somehow there's not enough diversity, I think, in our business models to create interesting, alternative games. At least on the triple-A side of things, the top end market. Bottom end, all kinds of interesting things; a whole microcosm's breaking out. But you're not seeing very high end innovation happening, and I think that's a shame.

Have you ever given any thought to doing a smaller project in your studio so you can test the waters?

TA: Yeah! We think about it all the time. We may just be doing that at some point.

I mean I don't know if you ever looked at Double Fine. They made Brütal Legend for EA and it didn't [commercially] perform. They were sort of in a similar space as Enslaved, I think. A little left of center, and while it was a good game, and it sold well, it didn't sell well enough for the kind of investment that had to be put in to make that kind of game. And they split the studio into a multi-project studio where they're doing downloadable games.

TA: Again, I compare it to film. You can do a $200 million production -- like Prince of Persia, maybe -- and it just falls flat. And then you can do a $10, $20 million -- Black Swan or The King's Speech -- and it makes more money than all of those.

But there doesn't seem to be an equivalent in games. You can do those small downloadable games and things, but they don't break out like the big hits. You can't compete on the same level playing field -- whereas in film, you can.

I think if we go online with the big triple-A stuff, I think that will all change. Like properly embrace it -- break the publisher-retail stranglehold. I think it's strange that games that are released digitally -- purely digitally, triple-A games digitally online -- cost more than you can buy them in the shops. Why is that? Who decides that that makes any sense? So there's definitely something there holding it back.

There ARE a lot of artificial constraints on the digital channel, I think, at least on the console side right now.

TA: Yeah, it feels like a kind of self-destructive protectionism that's ultimately doomed to fail. And I think that change can't happen soon enough really for the benefit for developers and publishers and gamers.

How do you think it would benefit publishers?

TA: They won't be held hostage to this model that's so restrictive. They can release more games at different price points, different sized games -- they don't have to bet the farm on the one big blockbuster or the two big blockbusters every year.

They can test games before they push the marketing; like release them early, beta them, release the first episodes. Instead of deciding, "Oh okay, we've got three games in our portfolio. We think this one's going to be a hit, so all our marketing's going to go into that one, and the other one's going to have to sink." It's brutal.

So pipelines, in terms of production pipelines and the sort of the processes you grow. Do they become flexible enough that you can shift your priorities internally in your studio as you need them? If you change the way you want to work.

TA: We haven't really kind of encountered that. I mean not moving onto other platforms, if you were applying things like new platforms like iPhone and things like that. I don't know, I think it depends on the platform and technology. We're using Unreal, so moving to things like the iPad, that makes it easier.

The content has to change a lot because the interface is totally different, but it's doable. I think in the past we've created our own engine, we've licensed engines. Initially we've licensed Renderware for Kung-Fu Chaos, and then did our own engine for Heavenly Sword, and then Unreal for Devil May Cry. I don't know, I don't think technology is a big barrier like it used to be.

Yeah, it's definitely interesting to see people's solutions. Unreal has, in a lot of ways, moved into a de facto space with a lot of games, and you see a tremendous amount of different ways of using it over the course of the generation.

TA: Yeah, I think people are more concerned about business models and platforms than the technology now. What makes sense for the platform, how do you monetize that -- that seems to be the focus around the development community now.

Your studio is at least presently still working on, you know, concentrating on triple-A, disc based, $60, paid games. When working with an IP like Devil May Cry, you've got a certain level of insurance you didn't have with your previous products.

TA: Yes that's right, and at this stage in the cycle that's probably the only bet you can realistically make. It changes again when new technology, new platforms come in. But yeah, it gives us sort of an insurance.

It's the first time we've worked on a IP that we haven't created, and it's been really good actually -- there's been a lot of creativity that's gone into it. I think you're always creative when you've got boundaries, and we've got some boundaries for this game.

Insuring that the combat fits in with the feel of the old games, and the storyline, and things like that. But there's so much to innovate. So at least we know it's going to have a presence. So it's been positive in that sense.

You worked with a variety of publishers now, how do you feel about the publisher/developer relationship? It can't always be what you would hope it would be. But certainly you had some experiences now.

TA: By and large I'd say that [the relationships] are positive, very positive. But it's always a strained relationship in a sense, because as a developer you want as much time and resources as possible to make the best game you can -- at least, we do. And I think most developers do. And the publisher wants the same, but they want it as quickly and as cheaply as they can possibly get it. [laughs]

And so it's constant battle to... Actually, I wouldn't say battle. It's a constant process of trust -- trusting each other, and putting yourself on the line, and saying, "We need to do this, for this reason, and take a leap of faith." And if they take that leap of faith and it works out, then they'll take more leaps of faith. But it's difficult.

How do you foster that trust? I've talked to other developers; the word "trust" doesn't always come up in discussions like this.

TA: I think there are two powerful tools that a developer has. One is to be prepared to walk away. So just be prepared to walk away from a deal that's a bad one. And secondly, I think you have to just go into it openly; you have to go into it with trust, like any relationship in life. You have to go into it openly until proven wrong, I think. If you go into it assuming the worst, it'll just not work, I think.

It's business. You know, in the '80s you're taught, by watching movies, you're taught that it's all about wheeling and dealing and being scheming and lying and things. And actually I think business is not like that -- it's about being totally honest, and it's about relationships -- actually personal relationships with the different parties. So I think you've got to do that, just take that leap. It's difficult.

DMC

You mentioned walking away from a bad deal. You see a lot of independent developers enter into bad deals. Some of it's because they lack business acumen, and some of it's because they're over a barrel, right? So how do you avoid those things?

TA: If you're going into a bad deal, make sure you're getting something out of it. For example, it's allowing you, as a studio, to grow, or enter a space that you weren't in. But as far as possible I think you should hold out, and there's lots of -- now especially, there's a lot of ways to publish games -- lots of ways to get to market.

And I think that the power is shifting. I think it has shifted, on the smaller side of things -- not the triple-A side, but on the smaller scale of games -- that the power's shifting. So, I think, do everything conceivably possible to not repeat the old habits of the triple-A developer/publisher model with the new generation of platforms. I think everyone kind of owes it for everyone else's sake as well.

And I think on the triple-A side so many developers have gone bust, have done exactly what you said, have got themselves over a barrel and gone bust, that there's not actually very many triple-A developers left. So to an extent, you can walk away, and you can talk to different publishers, and you can shop around as a developer. Personally, I would rather not be making games than to to be over a barrel. I think when you're at the point where that's your only option, I think it's time to get out anyway.

Prior to going independent, what was your background?

TA: I was at Millennium Interactive, a games company in Cambridge, and they then got acquired by Sony. So I was at Sony there as a programmer for three to four years, then eventually a designer. But they were famous for games like MediEvil on the PlayStation 1 and Ghosthunter on the PlayStation 2 -- which I wasn't a part of.

It's interesting to have made the move from programming to design. You don't hear about that all the time.

TA: I think I was on the tail end of that wave of people that learned to make games at home on their Commodore 64s and Amigas, and I did that because I wanted to create games. I think programming is a creative endeavor, especially in games, so I'm not too surprised by it. I thought it was one of the most creative times of my career, actually, programming. You have full control over what you create, and you appreciate the elegance of your own systems, even if no one else can see them. I really enjoyed it.

Do you feel you still have a technical grounding that helps with the business, and with the design of the games you're working on now?

TA: Yeah, I think so. I think because I know what is possible, I know that very little is impossible. So I'm less likely to be apologetic about advanced features. I've got a sense of the kinds of things that are easy to do -- big bang for buck things -- that maybe I wouldn't consider if I wasn't a programmer in the past.

You were talking about literal things you can take from film production. Film directors know a tremendous amount about how films are made, right? In all aspects and in all ways, whereas games can get disciplinary; a little bit isolated sometimes.

TA: Yeah. One of the best things about working with people from the outside is that it just gives you fresh infusion. And I think it's a healthy thing; otherwise we'd just keep repeating ourselves.

Sometimes you do kind of despair when you look around the room and everyone's... you see the same faces creating the same games, and everyone's white middle-class male. And from diverse backgrounds.

But you kind of think, "God, we're sending games around the world, to all kinds of people, from all kinds of communities, and yet they're not represented within the games community." And I think we should do that somehow, and we should accept creators from other industries to come in and feed us as well.

It's sort of like a pet issue of mine -- being influenced by things other than game culture and the ancillary geek culture. Feeding from different spaces and being just aware of what's out there. Even if you're going to end up creating something that's still typical.

TA: We're going to back ourselves into an elitist corner. [laughs] And then be totally shocked when someone comes along and does something that just breaks out, someone that doesn't think like we do, and has a different perspective. It's important.

Activision is doubling down on a specific audience. They're making Call of Duty and World of Warcraft the center of their world. Rather than saying "Strategically, we can expand things."

TA: It's difficult. I think we're always battling against what's current. Publishers make the decisions; everyone's too frightened to put their foot forward and say, "This is what we should do", because if you get it wrong, you're fired. So publishers are inherently conservative, and the way that they can arrive at what kind of game they should do is through consensus and focus testing.

If you put a bunch of kids in a room and ask them, "What kind of game do you want to make?", "What kind of hero do you want to be?", they're going to say "I want to be a space alien" because they just played Gears of War, or "I want to be a gangster" because they've played Grand Theft Auto, or "I want to be a cowboy" because they've played Red Dead Redemption.

So if you took them something like The King's Speech and said "How about a film where you want to be a speech therapist and you're helping a quaint king in old London?", they'll say "No, I don't want to watch that!" Yet somehow in the movie industry they allow it; there's a system that allows kind of these projects to go forward, whereas in games we don't allow them to go forward.

Well it kind of goes back to what you said about, you know, like Prince of Persia flopping and these movies being tremendous hits; there's a certain insurance there. The bombs are carried by the successes.

When people go to movies, you know, no one goes into The King's Speech and thinks, "Well, this isn't going to have 200 million dollars of special effects." Whereas with games, if your game doesn't look as good as Gears of War, or whatever, people get a little bit...

TA: Oh yeah, because again, I think that's the price point thing. If you're paying 60 bucks for a game, you want it to give you everything under the sun. I would give games more of a chance if they were at different price points, as I think that would make sense, because it's not possible for a low budget game to compete with a super high budget game, technology-wise, anyway.

Though I honestly don't know what was spent developing it, but I do feel like Heavy Rain was sort of The King's Speech of this generation. They've been public about the fact that it sold more copies than they anticipated. I know that Sony, in America, didn't market it very much at all; they didn't do TV ads for it in America, and it sold well beyond expectations. It was also different than pretty much anything that it was competing with.

TA: Yeah. I don't know how much it sold -- I mean I don't honestly know how much it sold -- but I suspect it's still not comparable to The King's Speech just sweeping the board and everyone wanting to see it.

Probably not, yeah.

TA: I don't know that it is quite The King's Speech. It is in terms of that it is a movie-like story. But I don't know, it still feels like something's missing. It feels like there's a creative opportunity in games that's not being taken advantage of. I don't know.

Kellee Santiago of Thatgamecompany ha said that when they sat down with this idea that they wanted to make games that are designed to evoke emotion through play, it turns out it's harder than they anticipated. Because there's been years iterations on combat mechanics. Not so much iteration done on other things, other forms of interactivity.

TA: Yeah, that's true. I don't think you should confuse the interface with the content in such regard. So I think, for example, you can do an FPS that focuses on emotional impact, and do it extremely successfully. I think that the games that are extremely successful are successful despite their stories and their emotional involvement.

I'm still waiting for that game that manages to do both extraordinarily well, and I think it's just around the corner. I think there's been just a few near misses, really. But when it hits, I think the attitude that stories don't, somehow, make a game feel better, make it feel more an experience, will go away.

What do you think is causing near misses?

TA: I think it's cultural. I think there's not many people in games that are experienced storytellers, filmmakers, etcetera. I don't think they always invite those people along to raise the game; I don't think they use the right techniques often to convey emotions. And I think that the game production is so difficult that it has to take second fiddle, really; it just has to.

I've talked to a lot of people about how difficult it is to integrate story into the process.

TA: It needs to be cultural, it needs to. Like in movies, every single person that's on set -- that's the crew, that's every single person involved in the movie -- is serving the story. They all understand the story and the importance of it, and they understand that their part is to serve the story.

In games, that culture doesn't exist. So if you want to be successful with that, it needs to be from every person in the studio, to the publisher, needs to be supporting the idea that they're serving the experience. It's not even story, I think. It's the experience -- it's serving the experience. Story's wrapped into that. It's a very hard thing to break habits.

I think there's definitely multiple ways people look at games. Some people look at them experientially; some people look at them more mechanically.

TA: No, I agree. I guess we're focused on story. We're focused so much on story, because that's the area I understand best -- story-driven games, that is. But there's room for all kinds of games. And all genres shouldn't necessarily have a story. I'm not that interested in creating games that don't have stories, because I like stories.

People like stories. I think that's why we always come back to putting story into games. As you said, there are some people who say that they shouldn't have them at all.

Similarly, you'll see people say that games shouldn't be single player, because games inherently evolved naturally as interaction between people, right? But then again you always turn around and say any medium just evolves via the people who work in the medium, and their drives.

TA: Yeah, and it's messy. It's like, what do people like? People like different things, so it just gets messy. I think games have long branched away from the early days when it was very limited. I don't even know if "game" is the right word for it anymore; it's just too diverse now, too big.

Something you said that I thought was really interesting is that when you're doing the read-through of the script, and you see a lull in the story, that can often tell you there's a lull in the game. I was wondering if you'd go into that a little bit more.

TA: I think one of our jobs as creators is to create a world that's believable, that allows a player to forget that they're playing a game, and they're just involved in this world. And it's so easy to break that illusion if just one thing that works wrong. Like a door that doesn't open. If you can shoot 10 doors, and they can break open, and one of them doesn't, you're immediately broken out of the illusion. So preserving the illusion of the world is the most important thing you can do as a creator.

So if you're creating a story, it's about creating this evolving illusion; it's defining this world that you're in. So if that world, if the story, starts to lull, you can bet that everything wrapped around that story -- which is also the gameplay and the experience the player's having -- will also lull.

I guess it just signifies that you've got to deal with this experience as a whole, both story and gameplay, and all aspects of the mechanics, and audio, and everything, are all part of one experience. And if one bit, or part of it lulls, it can drag the rest down with it.

I know that when you say "lull", you mean the game's dragging. But definitely in stories, you need up and down moments, right? So how do you work with pacing in that regard?

TA: Well, it's the same as editing. Like, scenes can drag on too long in editing -- you cut those scenes, or you insert something at those points. I mean, you're right that there's lows and highs and peaks and drops, so you've just got to make sure that that's happening regularly enough.

You record all the performances in advance. You might not have the flexibility you need; you can't really do reshoots. So how do you re-pace a game, from a process prospective?

TA: One thing I've learned from Alex, actually, is how much cheating goes on in film. I was quite surprised, and shocked, at the amount of editing that happens, the amount of cheating that happens during the editing phase. So if a film doesn't work, they do all kinds of things -- take the same scene from a different angle, and insert it in different parts of the film. Lots of back-of-the-head shots where people talk, and they insert dialogue that way.

And a large chunk of the films that we watch are shot like that, all the way through, and you can totally do the same in games. So even if we haven't got the scene, we can reconstruct the scene from different motion capture, from different scenes. In fact, the entire ending scene of Enslaved was done that way; none of it was captured. It was constructed from different scenes that we had. You can do all of that very easily, especially with motion capture.

Why'd you end up having to do that in Enslaved?

TA: I think it was because the original scene as we had it... We went through it, we read through it, we shot it. Alex watched it, and he said, "This doesn't work." And it's something that happens very often in movies, where a scene just doesn't work. And he said, "Let's forget about it for a second. If I was to rewrite it, this is what I would write," and so he just rewrote it again, and said "In an ideal world, this is what we'd do."

And I said, "We haven't shot that." And I was saying that all the way through, as he was writing; "We haven't shot that," "we haven't shot that." And he told me to just be patient waiting for it, and then he explained that in movies they cheat all the time, and scenes that don't exist, they can create.

I tell that the guys back in the office, and we reconstructed the scene, and figured out how to do it with just stuff that was left aside. We bought a five thousand buck little mo-cap studio in our office, USB-based, and we could create character performances that we didn't have, to fill in the gaps and... I think it's just part of the process.

And did you have to record new audio?

TA: Yeah, we recorded new audio. In fact, we filmed Andy Serkis, In the final scene, he appears in video from the real world, and we just recorded him in a voice recording session, and put that into the game as well.

Something you also talked about was watching back the whole thing; it sounded like you watched back the whole recorded performance, as though it's a film.

TA: Yeah, we do.

And you edited it to lock that pacing in.

TA: Yeah, exactly like you would in a movie. Everything we've shot is shot on video; it's edited by a film editor. And yeah, you can do that; it just seems to work. If something feels wrong in just the viewing of the cutscenes, it seems to feel wrong in the gameplay as well. I don't really understand exactly why, but it just does.

That's interesting, yeah. I don't understand exactly why, but trust your gut, right?

TA: Yeah, a lot of it is gut.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like