Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In its twenty-five years of existence, Electronic Arts has grown from a modest start-up to the world's largest games publisher. Gamasutra explores EA's history, with insight from founder Trip Hawkins and current EVP Frank Gibeau, in this in-depth special feature.

Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins had a lifelong fascination with games. "I fell in love with complex board games like Strat-O-Matic and Dungeons & Dragons," he told us. "I realized I was making invaluable social connections from playing games and that my brain was more active."

"In the summer of 1975 I learned about the invention of the microprocessor and about the first retail store where a consumer could rent a timesharing terminal to use from home," he remembered. "That very day I committed to found EA in 1982. I figured that it would take seven years for enough computing hardware to get into homes to create an audience for the computer games that I wanted to make."

After graduating from Harvard, Hawkins moved across the country to pursue an MBA at Stanford, a decision that placed him at ground zero of the personal computer revolution.

"When I finished my education in 1978 I got a job at Apple. When I started there, we had only fifty employees and had sold only 1,000 computers in the history of the company, most of them in the prior year. Four years later we were a Fortune 500 company with 4,000 employees and nearing $1 billion in annual revenue."

Machines that had once filled entire rooms at universities could now be had for less than $500 dollars and fit nicely on a corner desk in the family recreation room. Affordable microcomputers like the Apple II, Commodore 64, and Atari 400/800 brought real number-crunching power to the average person, allowing them to figure their income taxes, write school reports, and of course, play games.

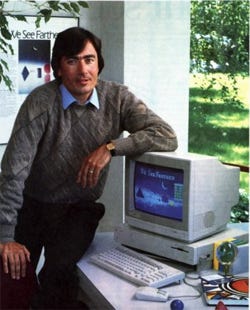

Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins

Flush with cash from Apple’s IPO, Hawkins knew that it was time for him to make his move. "Right on schedule, I resigned from Apple in January, 1982, but they convinced me to stay a bit longer. I finally left for good in April and on my own I incorporated EA on May 28, 1982. I personally funded it for the next six months. Initially, I worked by myself out of my home, and then in August began using an office at Sequoia Capital, where I also began hiring the early employees." San Mateo, California would become their permanent headquarters for many years until a 1998 move to nearby Redwood City.

The only thing left to do was come up with a name. "The original name had been Amazin' Software. But I wanted to recognize software as an art form and wanted to change it to SoftArt. But Dan Bricklin of Software Arts asked us not to use that name. So, in October of 1982 I called a meeting of our first twelve employees and our outside marketing agency and we brainstormed and decided to change it to Electronic Arts."

From the beginning, Hawkins had an ambitious view of what games could be. "We learn by doing," he said, "and computer simulation was the most efficient way to do this. I wanted to help the world transition from brain-deadening media like broadcast television to interactive media that would connect people and help them grow."

Hawkins also wanted to properly credit and compensate the talent that produced games, giving them the same respect that artists in other media enjoyed. He envisioned Electronic Arts as a publishing company that would be known for its quality and professionalism, working with the best independent talent to make the computer game industry equivalent with film, books, or music.

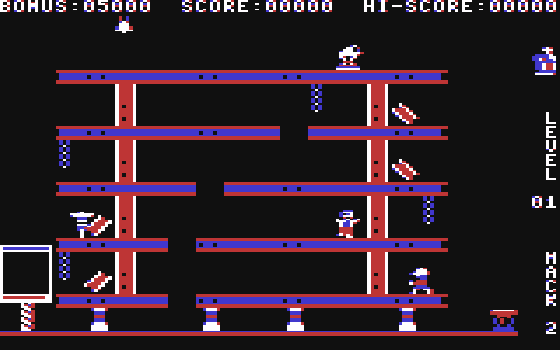

Electronic Arts shipped its first titles, Hard Hat Mack, Pinball Construction Set, Archon, M.U.L.E., Worms?, and Murder on the Zinderneuf in the spring of 1983. The games were packaged in unique gatefold sleeves, with the designer’s names on the front and an elegant graphic design that gave them the hip appearance of rock albums.

A majority of Electronic Arts' 1983 line-up. From left to right: Hard Hat Mack, Pinball Construction Set, Archon, M.U.L.E., Worms?, Murder on the Zinderneuf, Axis Assassin, Word Flyer and The Last Gladiator

"It was a pleasant surprise that the media quickly embraced my vision and lifted the profile of the company," Hawkins remembered. "In hindsight, my choices of the first round of products turned out amazingly well. Of the first six games, three of them ultimately made the Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame, and a fourth one charted on the bestseller lists of the day."

EA's rock star artists, from the infamous "We See Farther" 1983 advertisement.

Left to Right, Top: Mike Abbott (Hard Hat Mack), Dan Bunten (M.U.L.E.), Jon Freeman (Archon designer), Anne Westfall (Archon programmer), Bill Budge (Pinball Construction Set) Bottom: Matt Alexander (Hard Hat Mack), John Fields (Axis Assassin), David Maynard (Worms?)

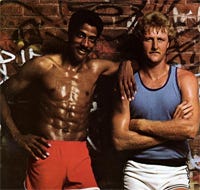

Julius Erving and Larry Bird, EA's first sports celebrities.

Another early hit for EA was Doctor J and Larry Bird Go One on One. Released in 1983, the basketball game enjoyed healthy sales, boosted by the involvement of sports stars Julius Erving and Larry Bird.

"EA Sports really originated with One on One," Hawkins explained, "which I designed, and where I introduced the business practice of involving celebrities in the design and promotion of video games."

To build its business, Electronic Arts had to aggressively upset the traditional rules of software publishing. Determined to set his own terms, Hawkins reduced the discount that EA would give software distributors, keeping more of the profits for itself.

In the fall of 1984, Larry Probst joined the company as vice president of sales. Probst brought an unparalleled level of organization to EA's strategy of bypassing distributors and dealing directly with retailers, causing its already successful market presence to grow even further. With its increased sales potential, EA began to distribute games from other companies, including Lucasfilm Games, SSI, and Interplay.

Meanwhile trouble was brewing in the world of console video games that would soon undermine the entire industry. Since its introduction in 1977, the Atari VCS/2600 home console had dominated American living rooms.

In the console’s halcyon years, Atari poured millions of cartridges into retailers, feeding a customer base that was hungry for anything new to plug in. Third-party publishers, eager to cash in on Atari’s success, blossomed in a market that seemed limitless.

In the console’s halcyon years, Atari poured millions of cartridges into retailers, feeding a customer base that was hungry for anything new to plug in. Third-party publishers, eager to cash in on Atari’s success, blossomed in a market that seemed limitless.

However, by 1983 the machine was aging. Consumers were losing interest and there was no coherent plan for what would follow. As the market softened, the small, undercapitalized publishers were the first to die off, leaving retailers little choice but to drastically discount unsold cartridges that they had previously been able to return for credit.

This brought about an accelerating chain reaction of price cuts across the board and vast warehouses of unsold merchandise soon piled up. By the end of 1984 the implosion was complete. Retailers were burned out, publishers were decimated, and customers walked away, leading many to believe that video games were just a fad whose time had passed.

The stink lingering over the video game industry was so bad that it spread to personal computers as well.

"Atari's meltdown created a tsunami that wiped out public interest in games, retail support, media interest, and gave gaming a stigma that lasted a decade," Hawkins remembered.

Electronic Arts was forced to revise their business plan in order to weather the lean years following the crash.

"I made a conscious decision to ignore Atari and to focus on the next generation of technology," Hawkins said. "We had to operate like the Fremen of Dune, recycling our own saliva to live in the desert, to survive. We had to rebuild the industry brick by brick over a period of years."

1988's Wasteland, an early RPG from EA

Although EA’s original marketing had focused on promoting individual game designers, the company quickly realized that consumers were more attuned to the games themselves. Designers were still credited, but EA’s marketing shifted in favor of game genres and building brand recognition.

The success of One on One taught EA the power of tying popular sports figures to game properties and a series of licensed sports games followed, including Jordan vs. Bird: One on One, Ferrari Formula One, Richard Petty’s Talladega, and Earl Weaver Baseball.

As it grew, Electronic Arts built a diverse catalog of games over the 1980’s. Titles were produced across multiple computer platforms, from the Apple II and Macintosh, to the Amiga, Commodore 64, IBM PC, Atari 800, and Atari ST. Some of the highlights included The Bard’s Tale, Wasteland, Starflight, and Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Trainer. EA even branched out into productivity software, publishing Deluxe Paint, one of the key applications for the Amiga computer.

Initially, Hawkins had little regard for the wounded console market, and felt that the personal computer would be the dominant entertainment platform of the future. However, as the Nintendo Entertainment System brought some stability back to the business, EA began its first in-house development with Skate or Die, which was published by Konami in 1988. Electronic Arts itself would not truly begin publishing console games until the era of the Sega Genesis.

"Once we were publishing for Genesis, we did go back and publish a few titles for NES, like Skate or Die 2," said Hawkins. "But it was a token effort. We did a lot more titles for SNES later on when it came out, but the Genesis was the real focal point, because I negotiated such a favorable deal."

EA developed both Skate or Die and Will Harvey's The Immortal for the original Nintendo Entertainment System.

Hawkins was cautious in dealing with Nintendo, seeing their strict licensing terms as an impediment to EA’s profits. He also felt that Nintendo's 8-bit hardware was underpowered.

"Because we had been 100% on floppy-disc based computers with more RAM and full keyboards, our technology base was well above the consoles," he explained.

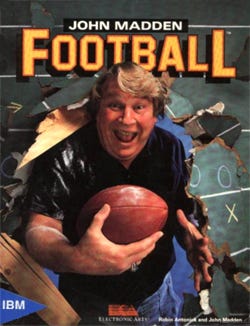

"With my lifelong interest in football simulation, my oldest friends would tell you that I founded EA to give myself an excuse to make another football game," Hawkins said. "I designed the precursor to Madden Football in 1970 as a board game called Accu-Stat Pro Football," a game that would be his very first entrepreneurial effort, funded by a loan from his father.

1988's John Madden Football, the first

game in a very long and consistent

franchise.

"After that I programmed another precursor to Madden as a school project in 1973, that was written in BASIC and ran on a DEC PDP-11 minicomputer. It simulated the January, 1974 Super Bowl and predicted the Dolphins would beat Minnesota 23-6, which was pretty good considering the real game was 24-7."

EA had published an early football title called Touchdown Football, but it was the success of One on One and its sequel that encouraged Hawkins to make another attempt at an in-depth football simulation. To enhance the game’s authenticity, Hawkins sought out Oakland Raiders coach John Madden to help bring the complexity of pro football to life on the computer screen.

"I picked John because I wanted a design partner that could help us make the game authentic but also have selling-power from his name on the cover," Hawkins said. "After signing him, I flew to Denver with my programmer and producer and went over my game design. We spent two whole days on the train with him going over an incredibly long list of details about football and it helped me finish the design properly.

"We'd get together periodically after that initial session to review our progress, and John would yell and scream about details we had wrong, and it was a lot of fun!" Their hard work paid off when the game was released in 1988, establishing EA’s best-selling and longest running franchise.

While EA was focusing most of its efforts on personal computer publishing, the flat-lined console business was being systematically revived by the determined efforts of Nintendo. By 1989, Nintendo’s sales had grown to almost $2 billion, and EA could no longer afford to treat consoles as a sideline. Other companies were also eyeing the market and later that year Sega brought the 16-bit Genesis to America.

Like many third party publishers, EA was leery of the console business. "Nobody liked paying high royalties under restrictive licenses, and what made it even worse was having to build ROM cartridges at great cost and inventory risk," Hawkins explained. However, with the arrival of the Genesis, he saw an opportunity to once again rewrite the rules of publishing.

Like many third party publishers, EA was leery of the console business. "Nobody liked paying high royalties under restrictive licenses, and what made it even worse was having to build ROM cartridges at great cost and inventory risk," Hawkins explained. However, with the arrival of the Genesis, he saw an opportunity to once again rewrite the rules of publishing.

"The Genesis appealed to me for many reasons, but a big one was that it had an MC 68000 processor," he said. This chip was key because EA had years of experience with the processor, which was also used in the Macintosh, Amiga, and Atari ST computers. Electronic Arts was able to quickly reverse engineer the Genesis and develop software that would run on it without Sega’s help.

Using this knowledge as leverage in his negotiations with Sega, Hawkins threatened to release games for the Genesis without a license unless Sega agreed to more favorable terms for EA. It was a very risky move that could have had expensive legal consequences.

Fortunately, Sega recognized the benefits of working out a deal with Hawkins. EA had an extensive back catalog of quality games that could be quickly ported to the Genesis, and a strong sports line that would be essential for the console’s success in America. It was going to be a hard fight against Nintendo and Sega needed all the help it could get.

Now that Hawkins had committed to consoles, he had to sell his company on the decision.

"It was very contentious because many employees and developers did not like consoles, or did not like action games," he said. "The goal was to stop making esoteric products for an elite customer base, and go make it in the big-time with mainstream gamers. Several employees were outraged and quit, but I convinced the team that if the public chose to buy consoles like the Genesis, then to satisfy our customers we had to make the best games possible on the platforms chosen by the public, not the ones our engineers wished they could afford."

Electronic Arts had its Initial Public Offering in the fall of ‘89 and used the influx of capital to push hard into console publishing. "I was flogging my development organization to put three new games into production every month for a year, plus we added twenty three games through affiliates. Sega was blown away at how fast we built a dominant product line," Hawkins said.

As EA aligned itself with the Genesis, a rush of games commenced in 1990 with a port from the Amiga of Peter Molyneux’s Populous, Budokan: The Martial Spirit, and John Madden Football. Over the six year life span of the Genesis, EA would establish several long running franchises, including the Strike series, NHL Hockey, NBA Live, FIFA Soccer, and Road Rash.

Electronic Arts also brought complex strategy and RPG titles over from personal computers. Titles such as Power Monger, Syndicate, Starflight, The Immortal, Might and Magic II: Gates to Another World, Centurion: Defender of Rome, and King’s Bounty appealed to older players, helping to widen the console game audience beyond its kid orientation.

EA's early Sega Genesis line-up was the publisher's first real push into the home console space.

Things move quickly in the publishing business, and Hawkins was already looking ahead. "After scoring a massively favorable license with Sega, I knew I had a big bull's-eye drawn on my chest, because the console guys would make sure I could never repeat what I had done with the Genesis. And on the PC side, nothing was going on that would advance the cause of the gamers and the game industry," he recalled.

Hawkins always had a keen awareness of technology cycles. "I knew the Genesis would give EA a great ride at least until 1994, but was afraid for what would happen after that," he said. Even as his company was diving into cartridge-based games, Hawkins sensed that a future of faster processors, low-priced memory, and easy to print CDs was just around the corner.

Hawkins always had a keen awareness of technology cycles. "I knew the Genesis would give EA a great ride at least until 1994, but was afraid for what would happen after that," he said. Even as his company was diving into cartridge-based games, Hawkins sensed that a future of faster processors, low-priced memory, and easy to print CDs was just around the corner.

"I thought the industry needed [a console] to push forward with 3D graphics and optical disc media and networking capability. Nobody was doing anything, so it seemed like the window was open," he said. Wanting to pursue development on the next generation of console hardware, Hawkins appointed Larry Probst as EA's new CEO in Fall 1991, and started a new company called the San Mateo Software Group, which soon evolved into The 3DO Company. Hawkins remained as chairman of the board for Electronic Arts until his resignation in July of 1994.

When Frank Gibeau, Electronic Arts' Executive Vice President and General Manager of North American Publishing interviewed at the company back in 1991, he was fresh out of graduate school and looking to get in on the ground floor.

"From the moment I walked into the lobby to drop my résumé off, I fell in love with the place. It was filled with Nerf balls, there were monitors going with games everywhere, and everybody was really laid back," he recalled. "People were playing games, shouting, yelling, and running around. It felt like a really cool company on first impression. I just went for it and interviewed like hell, got the job and never looked back."

Frank Gibeau

Starting out in EA’s marketing department, Gibeau could tell that the company was moving into a new phase. "There was a vibe inside the company that felt like things were really going to go fast.," he recalled. "There was a lot of stuff that was about to pop, and everybody had this keen sense that we were going to be part of something big.

"We didn’t know what it was going to be, I don’t think anybody had a business plan or a vision that said, ‘This is what the Sega Genesis is going to be like and this is why video games are going to be huge.’ The one guy who had the game plan was Larry Probst. Positioning the company there was going to be a big risk but it could have a big pay out, it could change the company and it did happen really fast,"

When Nintendo brought its Super Nintendo Entertainment System to North America in the fall of 1991, Sega had already gained a significant portion of the marketplace. Over the next four years, Sega and Nintendo battled for the number one spot in a vigorous competition that expanded the video game market, edging it closer to mainstream entertainment.

Electronic Arts benefited from the success of both companies, bringing its Madden, NBA, NHL, and Strike franchises to the SNES, while continuing to enjoy healthy sales on the Genesis.

"So, a lot of things came together," Gibeau said. "And there was this explosion of activity and growth."

When Electronic Arts was founded, most development was done by individual programmers who had a personal vision of a game that they wanted to create. However, by 1990 the days of game designers working out of the garage were long gone.

Large teams of specialized talent were now required to create the complex and visually exciting games that consumers demanded. Development teams needed the kind of money, organization, and marketing that only big studios could provide. EA had grown along with the industry and now that things were booming, it was critical for the company to keep pace.

Electronic Arts purchased its first outside development studio, Distinctive Software, in 1991. Based near Vancouver, British Columbia, Distinctive had previously worked on the Hardball and Test Drive series’ for EA’s competitor Accolade. After joining EA, they set to work on several of EA’s sports franchises and created the long-running Need for Speed series. Distinctive was later renamed EA Canada and is now one of the largest studios in Electronic Arts’ organization.

In 1992, Richard Garriott’s Origin Systems joined the fold. The Austin-based studio would go on to develop new volumes in Garriott’s Ultima and Chris Roberts’ Wing Commander series as well as the groundbreaking Ultima Online. Other important games from Origin included Crusader, Privateer, and Warren Spector’s System Shock. AH-64D Longbow, the first installment in the Jane’s Combat Simulations series, was also developed at Origin.

Despite its successes, Origin had difficulty integrating with EA and in 1999, after the release of Ultima IX, Garriott left the company. Later, several of Origin’s high-profile projects were canceled and the company was dissolved in 2004.

EA’s next big acquisition came in 1995 when it purchased designer Peter Molyneux’s UK studio, Bullfrog. Electronic Arts had previously published Bullfrog’s Populous, Power Monger, Syndicate, Theme Park, and Magic Carpet games. As a division of Electronic Arts, Bullfrog went on to produce Dungeon Keeper and its sequel.

After spending time as a vice president of EA, Molyneux left in 1997 to form the independent Lionhead Studios. At Lionhead he created Black & White, which was published by EA in 2001. His old, studio Bullfrog, was eventually absorbed into EA UK in 2004.

Maxis was a company built on designer Will Wright’s ability to turn his intellectual obsessions into entertaining computer games. Influenced by system dynamics and architectural theory, he created SimCity in 1989.

The success of SimCity launched an enduring franchise that included SimEarth, SimAnt, SimCity 2000, and SimCopter. When EA bought Maxis in 1997, Wright set to work on a new project that would become The Sims, one of EA’s best-selling computer games.

The Sims reached the market in 2000, and Electronic Arts has continued to expand the franchise with a sequel, a massively multiplayer online version, and numerous expansion packs. Currently, Wright is working at Maxis’ studio in Emeryville, developing the highly anticipated Spore.

Westwood Studios was an early innovator in the real-time strategy genre with their game Dune II. Out of that game’s success came the break through hit Command & Conquer in 1995 and many sequels and expansion packs followed.

In 1998 Electronic Arts acquired Westwood. The studio soon produced Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun, a new sequel built on an improved game engine. Over the next few years Westwood continued to produce titles for the Command & Conquer franchise as well as a hybrid RTS/FPS called Command & Conquer: Renegade.

Westwood's Earth & Beyond, the Las Vegas-based studio's swan song.

In 2002 Westwood released Earth & Beyond, a complex massively multiplayer online role-playing game. Unfortunately, Earth & Beyond struggled to find an audience and EA shut it down two years later. Westwood was closed in 2003, and its remaining staff moved from Las Vegas to EA’s Los Angeles studio, where Command & Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars is currently being developed.

Acquiring these studios’ Intellectual Properties significantly enhanced EA’s portfolio of games, but as Gibeau explained, acquisitions also brought much needed talent into the company.

"You are looking at a business that, even today, has tremendous constraints in terms of the talent pool," he said. "The number of guys that can really make great games and are visionary about it, there’s not enough of them. When you’re working with a company, it’s great to be able to lock up the IP, but it’s also great to be able bring new talent to your organization so that you’re constantly growing and staying cutting edge."

EA's Need for Speed

franchise originated

on the 3DO

Hardware transitions are difficult times for the game industry. As consumers move up to the next generation of technology, the market is uncertain, with no way to know for sure which way the wave is going to break.

Throughout its history Electronic Arts has had to make difficult decisions about where to allocate its resources. As Gibeau explained, "You want to publish on the platforms that have some degree of success built in. Where there’s something interesting about that technology that will give it an edge in the marketplace, that the company that is making the hardware has the capital resources and the long view of the marketplace, that it’s going to be in it for a while and not fold up shop. Because you make investments in these systems from from a software development standpoint, you want to be able to leverage them over a long period of time."

When the 3DO came to market in 1993, EA’s Need for Speed game was an early demonstration of the machine’s next generation graphics technology. Electronic Arts was also a partner in Trip Hawkins’ new console venture, and they published a variety of titles for the 3DO including John Madden Football, Road Rash, and Wing Commander III: Heart of the Tiger.

Although the 3DO failed to catch on at retail, when the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation came to market in 1995, the American public was ready to make the transition to 32-bit consoles. EA was quick to make the jump, porting several of its 3DO games over to the new consoles along with updates for their flagship sports titles. It did not take long for Sony to pull ahead of its rival Sega in the marketplace, and Electronic Arts seized the opportunity to expand its console publishing business.

EA contributed both proven franchises, such as Road Rash and John Madden Football, as well as new IPs, such as Psychic Detective, Escape from Monster Manor and Immercenary, to the 3DO library.

007 - The World is Not Enough

Throughout the ‘90’s Electronic Arts brought many successful games to the PlayStation, and the company’s revenue grew along with the console market. In addition to further developing its EA Sports line, the company began to delve into movie licenses with the James Bond games Tomorrow Never Dies and The World is Not Enough. The Medal of Honor series got its start on the PlayStation and several of EA’s long running franchises received updates, with Soviet Strike, Populous: The Beginning, and Syndicate Wars. Electronic Arts also formed a partnership with the Japanese developer/publisher Squaresoft to publish their PlayStation titles in North America, helping to bring Japanese-style role playing games to a mass audience.

The Nintendo 64 saw only a handful of titles from Electronic Arts. Its popularity lagged far behind Sony’s PlayStation, and Nintendo’s reliance on expensive ROM cartridges made EA unwilling to take inventory risks on anything but the most surefire hits. In addition to versions of Madden Football and WCW Wrestling, EA brought a well-regarded original title to the N64 called Beetle Adventure Racing.

Beetle Adventure Racing was among only a handful of titles published by EA for the Nintendo 64.

Electronic Arts entered the online market in 1997 when Origin Systems created Ultima Online, a persistent online fantasy world that could accommodate hundreds of thousands of players from across the globe. It was deeply ambitious and on a scale that was unlike anything attempted before. As Gibeau explained, "This was the first truly massively multiplayer graphic intensive game and it was a handful when we first put it out in terms of managing the technology, but it was incredibly innovative."

It was new territory for EA and despite some early difficulties, Ultima Online went on to be a huge success and is still in operation today. In the years since, EA has had ups and downs in the massively multiplayer online business. Ultima Online has done well for the company, but other efforts such as Motor City Online, Earth & Beyond, and hybrid online/ARG Majestic have had much shorter life spans.

Original packaging artwork from EA's first MMO, Ultima Online

In 2006, EA bought Mythic Entertainment, creators of the MMORPG Dark Age of Camelot. In addition to supporting Dark Age, the studio is currently working on Warhammer Online.

EA has also been providing online games for casual players through its Pogo.com site. The web site has a variety of free games and subscription-based premium games as well as a selection of games available for download. Pogo.com is partnered with AOL and includes a number of chat room features to keep players socially engaged. "Connected game play and the connected gamer is where the world is going. We see an incredible amount of opportunity, especially in Asia for us to chart a new path forward for the company," Gibeau said.

EA acquired mobile publisher

JAMDAT in 2005, allowing it

to publish hits such as Tetris.

In 2005, EA acquired JAMDAT Mobile, a successful mobile phone game developer and publisher founded by former Activision executives. Renamed EA Mobile, the studio has drawn on the wealth of EA’s Intellectual Properties to produce mobile phone versions of established hits such as SimCity and Tetris as well original titles like JAMDAT Bowling 3D and Orcs & Elves.

Digital distribution of EA’s graphics intensive PC and console games is a much smaller business, but the company sees future opportunities for its EA Link service. As Gibeau explained, "People have been forecasting the demise of the retail for decades haven't they? I think retail is fine. Downloading full product is pretty much a PC only phenomena right now.

"We have found that digital distribution is largely incremental and rewards your power users who can buy a lot of games. It also opens up avenues for paid downloadable content and other places where we can distribute content that wouldn’t necessarily be a retail good. Over time that will increase in significance most certainly, but full product distribution on the connected consoles is more problematic, just because of the file sizes and the size of hard drives there.

"I think it’s ultimately going to happen, but I also think that the stores are going to be around for a very long time. Especially if you look globally, in Europe for example," he said.

Sega kicked off the transition to the sixth generation of consoles by bringing its Dreamcast console to market in 1999, a year before Sony’s PlayStation 2. With game development budgets growing along with increased processor power, EA had to make a choice.

"We looked at the Dreamcast and we didn’t believe technically that it was that compelling of a system compared to what we thought was coming from some of the other companies like Sony," Gibeau remembered. "We didn’t like the economics of it, we didn’t think that it was going to be successful globally. We’re a global company, we have units all over the world and it’s rare that we can get the economics to work, or that it even makes sense for the hardware company, when they can only be successful in one market versus all three. So that was ultimately why we decided to go someplace else."

"We looked at the Dreamcast and we didn’t believe technically that it was that compelling of a system compared to what we thought was coming from some of the other companies like Sony," Gibeau remembered. "We didn’t like the economics of it, we didn’t think that it was going to be successful globally. We’re a global company, we have units all over the world and it’s rare that we can get the economics to work, or that it even makes sense for the hardware company, when they can only be successful in one market versus all three. So that was ultimately why we decided to go someplace else."

Sony’s PlayStation 2 was the odds-on favorite, but the console market was becoming more crowded. Nintendo was making a fresh start with its Gamecube and Microsoft was a new arrival with its Xbox console. As the largest independent publisher, EA’s tactic was to divide its efforts across all three platforms, insuring that no one manufacturer could claim dominance.

"Our basic competitive advantage is that we can publish games across multiple platforms simultaneously in a cost effective way and in multiple languages and deploy it globally better and bigger than anybody else," said Gibeau. "So when you look at that core sustainable competitive advantage and you look at the environment, you want to have as many platforms as possible out there to publish on.

EA's strategy allows it to publish games globally across multiple platforms. Pictured here: Madden NFL 2002 for the PlayStation, Game Boy Color, Game Boy Advance, Nintendo 64, PC, PlayStation 2, Xbox, and Gamecube

"When you have single platform environments like Nintendo 8-bit, basically all you do is what Nintendo tells you to do, back then at least. When you have a multi platform world, that increases the leverage of the third party publishing companies, because you can take your goods from one place to the other."

EA Sports led the way, with the PlayStation 2, Gamecube and Xbox all receiving updates to EA’s prime franchises. The Xbox also saw Cel Damage as an exclusive launch game from EA and, later, Oddworld: Stranger’s Wrath. The PlayStation 2 was a showcase for several high profile movie licenses including games based on the Lord of the Rings films, The Godfather, and a series of original James Bond games: 007: Agent Under Fire, Nightfire, and Rogue Agent.

Oddworld: Stranger's Wrath was published exclusively for Microsoft's Xbox console.

EA also secured the rights to J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series and produced several successful games based on the books. The Medal of Honor series flourished on all three consoles where increased graphic horsepower enabled the developer to produce an intense, cinematic experience.

Video games never had any difficulty appealing to young males, but the young female market was notoriously difficult to crack. For a company like Electronic Arts, which was founded on the principles of savvy marketing, that disparity was always a vexing hurdle.

"When you decide to build the Britney Spears simulation, you’ve lost," Gibeau noted. "It’s almost like you put so much pressure on yourself to figure out how do I make a game for girls that you screw it up."

However, the development of Will Wright’s game The Sims taught EA some important lessons on how to reach that under served female audience.

As Gibeau remembered, "It started out as an architecture sim with an interior design component, and then [Wright] put in people as little AIs just to see how they would work, and all of a sudden it became clear to him and to the company that the people were the most interesting thing on the screen and not the house designing part. What made it unique and different was that you’re creating and controlling people."

The Sims, EA's 'holy grail.'

He continued, "We launched it with the idea that we could get SimCity players and more casual PC players to pick it up. We never, at the time, thought that we could get teenage girls. We put it out into publishing and all of a sudden we started to see in the registration data and in the research that we had a tremendous number of teenage girls playing."

Realizing that they had inadvertently found the holy grail, EA’s marketing was quick to react.

"That’s when we started to change how we built the Packs, that’s when we went to Hot Date as a concept for the expansion pack, that’s when we started to buy advertising in fashion magazines and television advertising on MTV and female oriented TV shows. I think that right now The Sims are 66% girls under twenty five in terms of the buyer base. So we truly stumbled into it, but the part that makes me feel good about it is we were listening and watching who was playing and trying to learn from them."

For much of EA’s history, Europe has played a large role in the publisher’s success. In 1987, the company set up a European division to market games for the personal computer. Consoles were adopted at a slower rate in Europe and PCs, particularly the Amiga, remained the dominant gaming platform well into the ‘90’s. "That’s when our international business started to take off," Gibeau remembered.

Europe now accounts for over 40% of EA’s revenue, and the company has been investing heavily in European development. In 2004, EA added Criterion Software to its U.K. studio system. Criterion created the Burnout series of racing games as well as the recent FPS, Black. Criterion also produces the RenderWare game engine.

Gathering further European talent, in 2006 EA completed its acquisition of the Swedish developer, Digital Illusions CE, makers of the popular Battlefield 1942 series. Recently, EA also bought German developer Phenomic, creators of The Settlers and Spell Force.

As Electronic Arts makes its way through the latest hardware cycle, its success enables it to publish games across the technology spectrum. The graphic muscle of the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 allows games like Need for Speed: Carbon to provide a rush of sheer velocity while Tiger Woods PGA Tour 07 immerses players in a simulation so realistic one can almost smell the freshly cut green. On Nintendo’s new machine, Madden NFL 07 embraces the Wii’s controller in innovative ways.

The Criterion Software-developed Black

Future releases will see franchises like Criterion’s Burnout and EA L.A.’s Medal of Honor radically re-imagined for the next generation, while EA Montreal prepares a brand new IP called Army of Two. However, even as EA commits itself to providing state-of-the-art games for the latest consoles, the company recognizes the importance of casual games as the mobile phone, portable, and online markets become increasingly popular.

Art and commerce have always been uneasy bedfellows, and nowhere is that tension more evident than in the world of video games. Perhaps after looking at the history of Electronic Arts we may have some insight into that hot point of ignition where business and inspiration combine to create cutting edge games.

As Trip Hawkins explained, "Entrepreneurship is a creative art form. Like other creative people, we do it because we have to do it. We have no choice but to express ourselves in this way. But of course like all artists we are optimists, so we believe good things will come.

"It is not about making money, it is about making a difference."

Hard Hat Mack (Commodore 64, 1983)

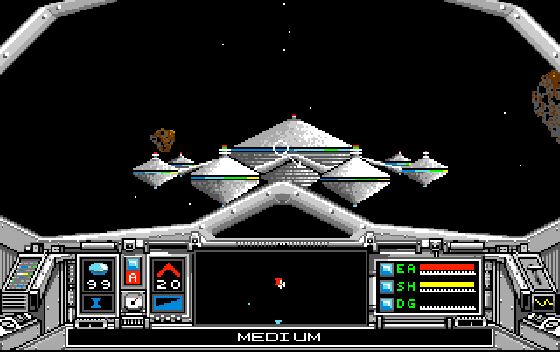

Skyfox II: The Cygnus Conflict (Commodore Amiga, 1987)

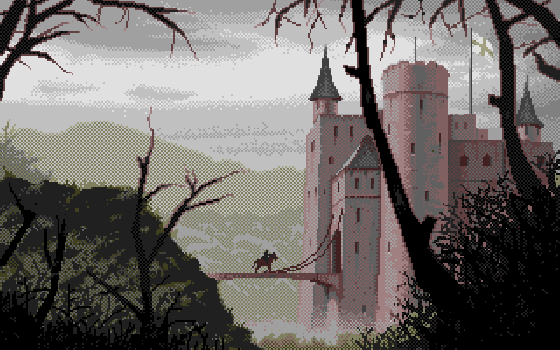

Powermonger (Commodore Amiga, 1991)

Wing Commander IV (MS-DOS, 1995)

Ultima IX: Ascension (Windows, 1999)

Need for Speed: Underground (PlayStation 2, 2003)

Fight Night: Round 3 (PlayStation 3, 2007)

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like