Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the second installment of his series on game preservation, John Andersen takes a look at the state of preservation in museums and academic archives, and examines the state of Japan's efforts to preserve its rich cultural history in games.

[Part 2 of Where Games Go To Sleep examines how video games can be protected by natural disasters and elements. Video game museums and preservationists worldwide reveal their goals and ask for artifacts from those in the industry. Meanwhile, Japan struggles to open its own video game museum amidst political controversy. Part 1, which looks into the surprising fates of historical Atari and Sega material, and more, can be found here.]

In August of 1986 Konami opened the Konami Software Development building in the Minatojima area of Kobe, Japan. 1986 was the same year in which Hideo Kojima, creator of the Metal Gear Solid series, would join the company. The Kobe building would house development divisions that were responsible for the production of Konami's most popular series. Development Division 5 was one of those divisions housed in this very building. It consisted of ten people -- one of whom was Hideo Kojima himself.

On the morning of January 17th, 1995 the Great Hanshin Earthquake struck the city of Kobe. It was the worst earthquake ever to hit Japan. 6,434 lives were lost, and the earthquake caused approximately $102.5 billion dollars in damage.

The Konami Software Development building was among many structures in Kobe that suffered damage. Kojima discussed how the impact of the earthquake personally affected him and his Development Division 5 colleagues in a Kojima Productions Report blog entry.

A retrospective video that played in July of 2007 during a Metal Gear Anniversary party told of how Kojima and his team were experimenting with early Sony PlayStation technology during the winter 1995 time period in which the Kobe earthquake occurred.

The same video would also reveal that Konami's Development Division 5 team lost an enormous amount of data and hard work in the Kobe earthquake. The quake eventually led them to relocate their offices to the Ebisu area of Tokyo, starting over, using Lego pieces to lay out preliminary designs of levels for what would become Metal Gear Solid for the Sony PlayStation.

Happily, it seems that some of Kojima's early Metal Gear design documents have survived, according to recent tweets he made, compiled by blogs Kotaku and Hachimaki.

According to IGN, Konami also lost much of the original artwork from the Castlevania series created up to the time of the earthquake.

The Konami Software Development building damage is listed within Konami's official corporate history. Konami Digital Entertainment in Tokyo was contacted and asked to clarify the extent of what development materials it lost in the Kobe earthquake. Konami's public relations division politely declined to comment, citing company policy not to discuss any information regarding the development of its games.

In the video game preservation questionnaire sent out to industry developers and publishers for this article, Sony Computer Entertainment of America was one of the respondents that did express the need for development kits and hardware tools to be kept in secure disaster-proof locations along with game data.

Many different industries such as medical, legal, entertainment, and manufacturing utilize one unique method to prevent loss from harmful elements or natural disasters: underground storage in a salt mine. Underground Vaults & Storage is a specialized storage company that provides six different locations for international clients. One of their locations based in Hutchinson, Kansas, has been in use for over fifty years; it is buried 650 feet below the surface of the earth and accessible only by secured elevators.

It is reported that major Hollywood film studios store their film negatives in this facility, and the master negatives for such films as Star Wars, Ben Hur, Gone With The Wind, and Journey To The Center of The Earth are secured at the Hutchinson facility. 20th Century Fox reportedly shipped twenty-two truckloads of film masters within a two-month period to Underground Vaults & Storage.

"The natural environment underground is perfect for storage -- a constant 68-70 degrees Fahrenheit and 50 percent humidity," says Jeff Ollenburger, business development and sales manager of Underground Vaults & Storage.

"Many of our clients recognize that they can safely and, just as important, economically, store their archives with us for decades and not take up valuable space in their own facilities. In the event that in 20 years there might be a need for that piece of information, it would still be available," says Ollenburger.

Underground Vaults and Storage also offers consulting services and unique data transmission services to its clients. Such services include certified records management and business impact analysis. "Using today's communication technology paired with on-site visits when appropriate, our team of experts can help any company develop a comprehensive records and information management strategy. While the decisions on what to retain and for how long are decisions to be made by each company and their legal or financial advisers, UV&S can offer 'best practice' strategies applicable across broad industries," Ollenburger says.

Ollenburger could not reveal if any of their clients include video game developers and publishers, but the welcome mat has been laid out for them, "Any organization, including those in the video game industry, interested in storing their information and archival material in one of the most secure locations on the planet would be welcome at Underground Vaults & Storage."

One secure establishment that video game developers and publishers could check for old material thought lost is the U.S. Copyright Office. Over the past few decades many developers and publishers deposited source code printouts, while others deposited "Identifying material deposited in lieu of game", such as a videocassette or a written description of gameplay.

Even though Irem disclosed in this article's questionnaire that they maintain no source code for any of their games from the 1980s in Japan, a search of U.S. Copyright Office records did uncover what appears to be Irem game source code. "Printouts" of what is assumed to be source code could be found for several Irem games including 10-Yard Fight, Red Alert, and Super R-Type.

It's unclear however if this is complete source code, as the U.S. Copyright Office currently requires the first 25 and last 25 pages of source code in filing for copyright of a computer program, or the entire code if less than 50 pages long. Source code printouts containing trade secrets can also be blocked out in certain filing circumstances.

Regardless, it should be noted that these copyright deposits are secure, and can only accessed if a written authorization is received from the copyright claimant, an authorized agent of the claimant, or an owner of any of the exclusive rights in the copyright.

There has been one increasingly important area of video game preservation; one could call it a safe haven for video game artifacts. This particular safe haven has been rapidly expanding over the past several years. It became apparent when one company, Fairchild Semiconductor, mentioned a particular museum while research was conducted for this article.

Fairchild Semiconductor was once a former video game console manufacturer that developed the first ROM cartridge-based video game system, known as the Fairchild Channel F, in 1976. The company, founded in 1957, was acquired numerous times and disappeared completely in 1987. Ten years later, Fairchild Semiconductor began operations once again, but this time in Portland, Maine.

"Most of the historical information was not retained over the years. I do have a few pictures and company newsletters, but nothing on the video game," commented Patti Olson, of Fairchild Semiconductor Corporate Communications. Olson referred us to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. An online search of its catalogued archives uncovered photographed artifacts entries for both the Fairchild Channel F and the Channel F II game consoles.

Gaming artifacts from computers, consoles and arcades have a place to call home -- a home that is now rapidly expanding.

A closer look at the efforts of video game preservationists uncovers an ongoing global effort to properly catalogue and archive all aspects of video gaming. This effort has ballooned just over the past five years with collections housed in major universities and museums.

These collections of artifacts are available to researchers, educators, and many are on display to the general public in special exhibitions. These specific organizations are continuously searching for items from those within the gaming industry, items that are in desperate need of preservation.

Along with the Computer History Museum, California is also home to the History of Science & Technology Collections, and Film & Media Collections, based at the Stanford University Libraries, led by curator Henry Lowood and his colleagues.

Lowood is head of a project established in 2000 titled: "How They Got Game: The History and Culture of Interactive Simulations and Videogames." Lowood is also chairperson of the Game Preservation Special Interest Group of the International Game Developers Association.

Since 2008 Lowood has been a co-principal investigator in a major project known as "Preserving Virtual Worlds", funded by the U.S. Library of Congress, this project includes collaborators such as Linden Labs, The Internet Archive, and several prominent universities.

The purpose of the project is to explore how institutions can preserve virtual interactive worlds and multiplayer environments. The "Preserving Virtual Worlds" project released its final report to the public at the end of August 2010.

Heading east out of California, one can find an expanding video game archive at the University of Texas in Austin. Here, the UT Videogame Archive was established as a collection component of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. The first three individuals to donate to the archive were game industry veterans Richard Garriot, Warren Spector, and George Sanger.

According to archivist Zach Vowell, he's helped establish fourteen collections so far, including Richard Garriot's first game, Akalabeth, and design documents for the Ultima series. Vowell has been going through artifact donation offers and is actively seeking "not only game software and hardware but also documents, art, digital records, promotional material, and business records related to all things video game".

Visitors enjoy some two-dozen coin-op arcade classics on display at the eGameRevolution exhibit at the ICHEG. The ICHEG currently houses more than 120 arcade games, and an online database for the collection has been established at the ICHEG website.

Journeying to the northeast United States, one can visit an exhibit that recently made its debut at the International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG), established within the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY. The ICHEG claims to hold one of the largest collections of electronic games and game-related historical materials in the world, with more than 20,000 electronic games, platforms and materials.

The ICHEG opened its eGameRevolution exhibit to the public on November 20th, 2010, covering 5,000 square feet, and featuring an authentic video game arcade with over two dozen playable classic arcade cabinets. Various exhibits intricately showcase the beginnings of the gaming industry. Home PC and consoles are also setup to allow visitors to re-experience classic games.

A close-up of an eGameRevolution display case with various video game artifacts at the ICHEG.

ICHEG also maintains Twitter and Facebook accounts with news on ICHEG events, as well as a blog. Preservation efforts are also chronicled on a blog from ICHEG staff members including Jon-Paul Dyson, director of the ICHEG. Its most recent acquisitions have included the donation of personal papers made by Will Wright, and artifacts from the family of late game designer Dani Bunten Berry.

Dyson points out in an ICHEG blog entry that Europe is also advancing in video game preservation efforts, "The Archivio Videoludico in Bologna is building a collection of video games accessible to both researchers and the general public. In Rome, ViGaMus - The Video Game Museum plans to open a public exhibition in 2011."

The ICHEG is also shipping artifacts to Germany, where they will be loaned to the Computerspiele Museum, which plans to open up a permanent exhibition in Berlin on January 21st, 2011. The Computerspiele Museum recently showcased their exhibit design concepts to the public via their website and official YouTube channel.

One important European institution advancing in game preservation is the National Videogame Archive (NVA), a joint project between the National Media Museum and Nottingham Trent University's Centre for Contemporary Play.

The NVA is actively seeking out further discussion with those in the industry on how to preserve all elements of gaming in the United Kingdom. These discussions have most recently occurred at a special NVA summit held during the annual GameCity festival in Nottingham during October of 2010.

The NVA has also launched a "Save the Videogame" campaign that has already attracted industry attention and artifact donations from developers that include Sony and Rockstar. The NVA and "Save the Videogame" are headed by Professor James Newman, Iain Simmons, and Tom Woolley.

The NVA also has a Games Lounge exhibit at the National Media Museum. The NVA continues to research opportunities where their current holdings of artifacts can be exhibited around the UK. Just recently, the British Library expressed its interest in collaborating with the NVA.

For this article, Lowood, Vowell, Dyson, and Newman were asked a few questions. Could one maintain the optimistic view that those involved in the video game industry (programmers, designers, directors, or producers) have held on to long forgotten source code and game production artifacts in their personal archives?

Going even further (to prevent these items from being thrown away) should game industry veterans be making efforts to ideally donate or bequeath these items to museums, universities and source code preservation projects?

Henry Lowood

Curator for History of Science & Technology Collections; Film & Media Collections

Stanford University Libraries:

"It is not just an optimistic view, but a reality. Indeed, individual employees (ranging from pack-rats to lab directors to people who just realize that they kept something by accident) have always been a primary source of materials for archival collections such as Stanford's Silicon Valley Archives. Game archives have already emerged by this route, such as the Spector papers at the University of Texas or the Meretzky papers at Stanford.

"There are two major differences between individual collectors and industry veterans, as opposed to cultural repositories like libraries and museums. First, individuals in companies can get to things that institutions cannot. Second, humans are mortal, while institutions live on. One of the main things that I do in my position as a curator is linking up the common interests of the two groups; it is mutually beneficial for them to work together."

Zach Vowell

Archivist, The UT Videogame Archive

The University of Texas At Austin

"Yes (to both questions). The scenario you outline in your first question precisely describes the way the UT Videogame Archive was established. Richard Garriott, Warren Spector, and George Sanger approached us, with the materials they had amassed over the years, not wanting that documentation to be lost to oblivion.

"Since then, other developers have been responsive and donated materials to our archive. So it can and does happen. Frankly, with the state of the industry's tight control over IP, it seems likely that developers' personal collections of documentation will be the primary way our archive grows, at least initially.

"I would invite all industry veterans with collections of documentation, games, consoles, magazines to at least get in touch with us and other repositories like us. If the materials are sensitive (say, still governed by an active NDA), we can place reasonable restrictions until it is legitimate to open the materials for scholarly research, exhibits, and other public access."

Jon-Paul C. Dyson, Ph.D.

Director, The International Center for the History of Electronic Games

"Some game industry veterans have held on to their materials, but unfortunately I've talked to far too many individuals who have lamented that they no longer have many of the materials they worked on.

"Generally this is becoming more of a problem as there are fewer and fewer physical aspects that are generated in the course of the game production process. Game designers from the early years often have printouts of code or design concepts, but those physical materials are less likely to be produced with modern methods of game production, and individual game designers are less likely to save purely digital assets when they leave a company.

"Yes, I believe that, if game industry veterans have an interest in seeing their craft preserved, then they should deposit materials with an established institution that can preserve them for the long term. Institutions can ensure that they are preserved for the long term as well as provide access to researchers hoping to understand the history of the industry. Too often, materials that remain in private hands will not survive, either because they are lost to some natural disaster, accidentally thrown out, or not kept by heirs."

Professor James Newman

National Videogame Archive

"We'd like to think so, and the NVA has had found the response from the games industry to be extremely supportive in this respect. It's worth reiterating, though, that our focus is broader than code. We're interested in telling the story of video games in all their contexts. We're as interested in players and the reception of games and their role in popular culture as we are in the code.

"So, while it's absolutely great when developers donate rare and even unique objects to the NVA collection, we must remind ourselves also that the mundane, everyday, ordinary parts of game culture or game development are just as important in telling the stories of games for future generations.

"We're not saying that a mass-produced Pikachu capsule toy is as valuable as prototype Rock Band controllers or a preproduction EyeToy camera, but all these objects are important parts of the story of video games. There is a tendency to preserve the big, impressive things -- the things that we all agree are important -- and the everyday things that we take for granted slip through the cracks and disappear forever."

Newman sums up the overall objective of the NVA, an objective that most recent established video game archives and centers share:

"Preserving the code base is only part of what we're interested in so our archival work extends beyond this in a number of ways. We're also interested preserving the physical alongside the virtual -- i.e. material objects like consoles, cartridges, discs, merchandising, advertising and marketing materials etc.

"Ultimately, we're interested in telling the stories of games, game development and gaming culture so, for us, fan-produced maps, walkthroughs, art, costumes, are an essential part of our archival work. Similarly, all the stories that developers and players have to tell about their experiences of making and playing games need to be documented before they too are lost. As such, code is one element in the wide range of materials we wish to see preserved."

One important aspect of video game preservation is not only the exhibition of artifacts for public display, but for the value they have in a classroom. Utilizing different elements of video games are valuable in education and game design schools.

Zach Vowell of the UT Video Game Archive brings up two artifact examples of how an educator can utilizing these elements in a classroom: "I personally (granted, I'm not a developer) see the value of studying, say, the audio specifications for Advanced Tactical Fighters (found in George Sanger's papers) to see what issues were being considered, what decisions were made, and how those decisions effected, for good or bad, the final product.

"I would think a game design student would find it helpful to read Warren Spector's Ion Storm correspondence with his team, to learn how a producer does his/her job (a job that's notoriously hard to teach, I might add)."

Heading to Japan, the establishment of an official museum dedicated to video games is one that has been fraught with ongoing challenges. The very challenge of opening a video game museum in Japan is one the author of this article is very familiar with. An attempt was made by the author to gather interest in opening an "International Video Game Museum" near Tokyo while residing in Japan on the JET, The Japan Exchange & Teaching Program.

A business proposal was written, submitted to two major business organizations in 2005, all with the intention of gathering interest from associated Japanese software developers and publishers. Despite efforts to push the concept forward, along with pinpointing an actual location for the museum, there was no interest from Japanese video game developers and publishers.

The project would be shelved in 2006 due to lack of interest. An application for a Japanese government-sponsored graduate school scholarship to further research the museum, intended as an international tourist attraction, was denied in 2008.

The Japanese government would find itself in a publicized political and financial conflict that made headlines when it attempted to open its own museum with a section dedicated to video games. This museum was then known as the National Center for Media Arts (NCMA), and the conflict was covered in numerous Japan Times articles.

The NCMA was aimed at researching, collecting and displaying manga, anime, video games and digital art. The plan was assembled and pushed forward for funding by Japan's Agency For Cultural Affairs. In April of 2009 it was announced that 11.7 billion yen of funding ($132 million USD) had been approved in a supplementary budget plan for the NCMA to be built from the ground up.

It appeared that the NCMA was moving rapidly forward, all under the watch of then-Prime Minister Taro Aso, a figure who made it well known to the public that he was an avid manga reader. The 10,000 square foot facility was to be built in Tokyo's waterfront Odaiba district.

The news was largely ignored by the media until then Democratic Party of Japan president Yukio Hatoyama blasted the plan, calling it a "state-run manga café". Hatoyama declared that the money set aside for the NCMA should be used for struggling single-mother households. Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs head Tomatsu Aoki noted that its overall agency budget for 2009 was 102 billion yen, about a third less than South Korea's, and seven times less than France, according to a Japan Times article which pointed out another official defense:

"...The NCMA plan's inclusion in the supplementary budget is that it will serve as a fiscal stimulus in the current economic downturn -- which is why the supplementary budget was created in the first place."

There were mixed reaction from those within Japan's popular culture industries about the NCMA plan. Some were for the NCMA while others were against it, arguing that the enormous amount of money budgeted for the museum would be better suited to directly support the working environments of employees (both current and prospective) of Japan's popular culture industries of anime, manga and video games -- all struggling amidst the impact of the financial crisis.

A Japan Times article covering the unfolding debacle in July 2009 interviewed 28 year-old Yujiro Funato, a producer at Realthing Inc., a company that produces animation and computer graphics. Funato did not hold back his criticism of the LDP (Liberal Democratic Party), blaming it for being too late in building the NCMA:

"It should have built it 20 years ago... Things are going in the wrong direction because they're talking about it when there is no money."

Funato also expressed skepticism about pledges to improve things for workers in the field: "Nothing is likely to change. The private sector should make efforts on its own," Funato said.

One month after this Japan Times article was published online, Yukio Hatoyama would be elected Prime Minister of Japan, defeating Prime Minister Taro Aso, removing the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from power for only the second time in 54 years.

In preserving video of actual gameplay, GameCenter CX is a Japanese television show that is accomplishing this feat. Numerous video game titles are played on each episode with the help of game guides and even on-set production staff. Host Shinya Arino visits game arcades all over Japan and interviews famous game designers in between game-playing segments.

Newly elected Prime Minister Hatoyama and the DPJ cancelled the construction of the NCMA, leaving its future uncertain.

It should be noted that many pop culture museums based in Japan were not immune to the financial crisis. A Robot Museum in Nagoya that opened in October of 2006 closed within a year. The Rock 'n' Roll Museum, a staple of Tokyo's Harajuku district, closed in January of 2010 after sixteen years of operation. The world's first John Lennon museum, located in Saitama, would close in September of 2010 after ten years of operation.

Many still believe there should be one single center dedicated to all aspects of Japan's pop culture. Since the NCMA plan was dropped, the Japanese government is proposing a new plan to bring together resources in collecting and displaying works in conjunction with conducting research.

This time the plan would be budgeted at just 250 million yen ($2.3 million USD), utilizing existing facilities, and sixteen different universities and organizations (including those based in the Australia and UK) would contribute to the effort. With regards to video games, Japan's CESA organization would contribute to the research sector.

One of the participants of this new effort is Meiji University, which has tentative plans to open a new library with exhibition space in 2014, called the Tokyo International Manga Library. Meiji's new library would not only preserve anime and manga, but it would also preserve commercial video games, home video game consoles and software. Meiji University's planned museum would join the established existence of local government museums promoting Japanese pop culture that include the Kyoto International Manga Museum and the Tokyo Anime Center.

It should be noted that even though these predicaments have occurred, Japan has not completely neglected its video game legacy. Efforts to preserve video games have been moving forward by Japanese game developers, publishers, game players, educators, and the mass media.

One Japanese educator has taken up the task of collecting every Nintendo Famicom cartridge in existence. Professor Koichi Hosoi established the Game Archive Project in 1998, based within Ritsumeikan University's College of Image Arts & Sciences in Kyoto.

Hosoi is a professor of the Graduate School of Policy Science, and also serves as vice-chairman of Ritsumeikan's Art Research Center, and is vice-president of Japan's Digital Games Research Association.

The Game Archive Project has collected nearly every Nintendo title available: 1300 in total, according to the Game Archive Project introduction page. The collection also has a nearly complete collection of Sega games, along with both mainstream and hard-to-find video game hardware.

Hosoi's Game Archive Project is hoping to not only archive every cartridge and system imaginable, but research emulation systems and methods to digitize play screen images in anticipation of the average 20-year lifecycle of hardware.

The Game Archive Project is currently seeking international collaboration to "formulate classification codes and metadata for organizing and preserving games on an international basis" in hopes of creating a web archive.

International audiences are not completely locked out of Japan's classic game history, as Japanese developers have released countless compilations and have made games available online. Project Egg is a notable online video game subscription service that is open to subscribers worldwide, providing over 600 Japanese computer games from the PC-9801, FM-7, and the X68000.

It is important to note that through the conclusive research conducted for this article, combined with the industry respondents of the game preservation questionnaire -- all were overwhelmingly supportive of the video game industry working together to preserve its legacy. It remains to be seen just how the video game industry itself will participate in preservation efforts worldwide.

One fundamental first step that developers and publishers could take is to build an inventory of what video game IP they own, and make release histories available on company websites. One unfortunate fact remains: some companies have actually lost track of what IP they own due to company restructurings, mergers, staffing turnovers, bankruptcies, and the overall passage of time.

Databases such as Moby Games and GameFAQs have provided a wealth of data when corporate release histories are nowhere to be found. These databases remain dependant on research and submissions from voluntary contributors, in particular, game players themselves.

Certain developers and publishers do reportedly employ archivists, however it's unclear just how many full-time archivists there are in the video game development and publishing field. An array of personnel and departments within developers and publishers are ultimately responsible for primarily making sure data such as source code is kept safe. When it comes to handling historical assets unrelated to actual data, some developers or publishers utilize their own marketing departments to handle preservation duties, that is, if such a policy exists.

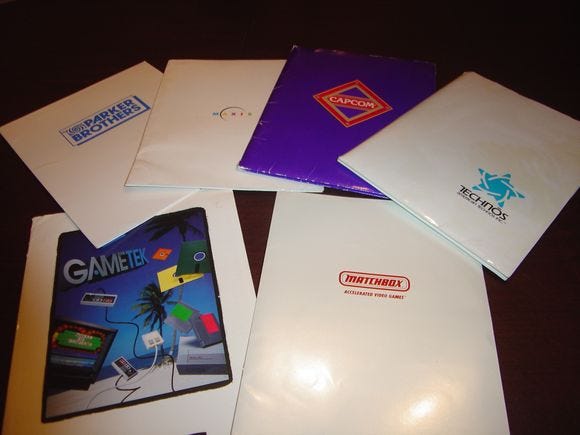

A collection of original press kits from game publishers Parker Brothers, Maxis, Capcom, American Technos and Gametek from the 1992 Summer (CES) Consumer Electronics Show. The Matchbox Video Games 1990 press kit (seen lower left) was not collected at the CES, but contains promotional material for NES games intended to be published by the Matchbox, including Matchbox Racers, Motor City Patrol, EuroCup Soccer, Sir Eric The Bold, and Noah's Ark. Matchbox Video Games, formerly based in Bloomington, Minnesota, was the Matchbox-branded entry into video games.

It appears now is the critical time for developers, publishers, designers and programmers to take stock of what is in their possession and conduct an inventory of artifacts that are important for preservation. Floppy disk and magnetic optical media will face erasure (if they haven't already) if not transferred to new, more secure media.

Physical materials, depending on the individual or company, will be destined for the landfill if not rescued, just as Atari Corporation's game engineering file cabinets were once destined for dumpsters. Everything is valuable; every piece can entertain new game players as well as educate and inspire individuals that are entering the game industry.

It may also be fair to go as far to suggest that any holder of artifacts, including devoted video game collectors, could consider bequeathing their collections of artifacts to museums and archives in a living will. Stanford's collection of video game artifacts, known as the Stephen J. Cabrinety collection, is one such example. Cabrinety was a software designer who passed away in 1995 at the age of 29. He amassed a large computer hardware and software collection that was later donated to Stanford by family members after his death.

The video game industry is one that is always in search of the next technological triumph, always revolutionizing and redefining itself in a constant loop. As we follow next-generation triumphs, vulnerability exists where one can miss out on what else is on store shelves and the digital marketplace. With rapid revolution and growth, one could even say that the industry fails to periodically stop and reflect on its triumphs, and even educate itself on its failures.

With the never-ending cycle of triumph, failure, vulnerability and the pressure to be on the edge of "next-generation" the industry and its consumers find themselves in a constant loop. All of this combined may lead to an overwhelming exhaustion, with many video games being passed by, forgotten or abandoned altogether. Perhaps now is the time to reflect and rediscover what makes us immerse ourselves in game play.

Out all of this, one thing is clear: The museums and archives are now open to collect -- prepared to fulfill their purpose. The intention of these features is not only to spotlight the game preservation crisis -- but also to spread word of worldwide archives and museums now awaiting artifact donations from those in the industry. These museums and archives will not only depend on the donation of artifacts, but also financial donations that will assist in the various steps in cataloguing these artifacts.

The purpose of these articles is to also promote further discussion on what more can be done about the video game preservation crisis, and support its new preservation movement.

As the clock keeps ticking, hardware faces breakdown, and storage media faces erasure. Many questions remain. What can the industry do to promote data refreshing and migration? In taking the discussion a step further, what storage media is the most reliable, and how should the paper elements of our industry, from game planning documents to marketing assets be digitized? Are our video games ready to be placed in underground storage next to the film negatives of major motion pictures?

There is now major hope for video game preservation, games now have better odds at not permanently going to sleep. Video games in a sense have taken care of us, provided us with entertainment, escape, and have even given us an entertaining, yet competitive social element that has brought us closer as a society.

Now is the time that we take care of the video game, providing it with the much needed maintenance, care and permanent tribute that it deserves. We've taken our game play seriously, but some would argue we haven't taken its origins and evolving triumphs seriously, leading to the decay brought forth in these articles.

It appears the greatest enemies of video game preservation are time, data obsolescence and the realization that the building blocks of the video game are dying. Now is the time to press the save button on the video game industry before the hardware, software and people that helped us press the start button are forgotten.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like