Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Science fiction author Neal Stephenson gently criticized cryptocurrency in games in his DICE 2023 keynote.

Here's a head-scratcher for you: what happens when a science fiction author who co-founded a web3 metaverse company built on the blockchain doesn't buy into cryptocurrency anymore?

That was the question on our minds at science fiction author Neal Stephenson took the stage at DICE 2023. Ostensibly his talk was meant to be a musing on the metaverse, but in a quirky twist, he instead spent most of the time talking about... Jack and the Beanstalk.

What was the point of Stephenson's dive into an old folktale? It's a story that centers a transaction for "worthless" currency (the magic beans), and per Stephenson's reading, a decent comparison point for analyzing why anyone would want to invest in cryptocurrency for buying and selling in-game items.

This was a notable speech for the founder of a web3 metaverse company to give. It might not only signal what kind of metaverse product his studio Lamina1 might create, but also how the millions of dollars of venture capital invested in similar businesses may pivot in the crypto winter.

Stephenson's call to the audience was this: when building in-game economies for virtual worlds, devs can't lose sight of the intrinsic value of items—what gives them their worth beyond just artificial scarcity. Here's a quick rundown of his thought process.

In Stephenson's analogy, the magic beans Jack sells the cow for (when he'd been sent to get...uh, FIAT currency) are a good stand-in for cryptocurrency. They're supposed to be able to do all these wonderful things, but in the end they only lead Jack to a violent world of wealth, power, and eventually doom and downfall.

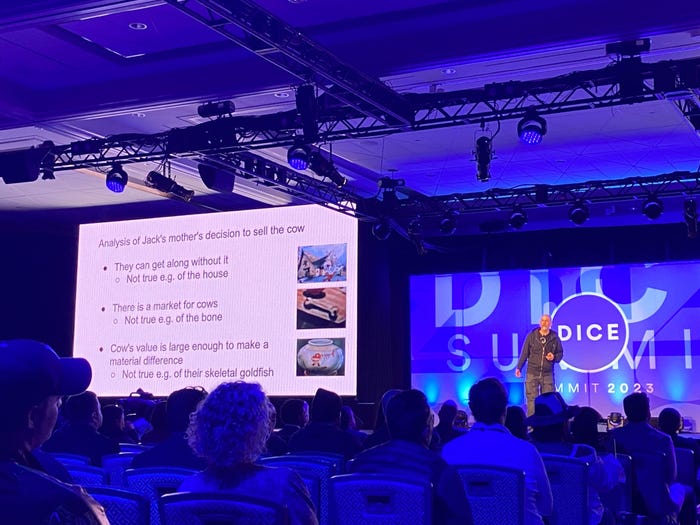

But Stephenson seemed less interested in the magic beans themselves and more about what Jack used to procure them: the cow. In Stephenson's analysis, what made this cow so valuable anyway?

The answer is clear in the context of the story. Jack's family is poor, the cow is starving, they can survive without owning it, there is a market for cows, and selling it will give them cash they can use to buy food.

Even before the blue-faced "cryptobro" enters the story (Stephenson was referencing a 1933 Comicolor animation of Jack and the Beanstalk) the incentive for Jack and his family to sell the cow was clear, and the heady promises of cryptocurrency (magic beans) made him sell the cow for bigger dreams than simple coin that could feed his family.

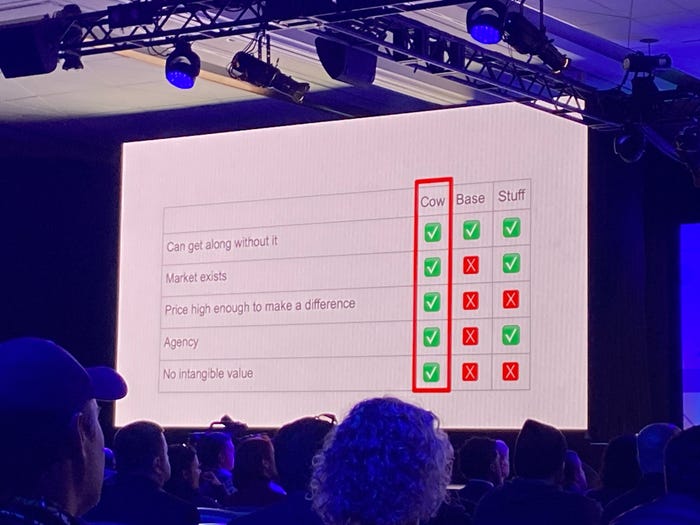

Stephenson then compared the cow to in-game items—specifically the ones he'd acquired in Viking survival game Valheim. In Valheim, Stephenson and his friends have built a modest base, crafted some fancy weapons and armor, and earned trophies that hang on the base's walls.

Now Stephenson mused, why would he and his friends want to sell this base? And more importantly, what made these respective items valuable?

Comparing it to the cow only produced one key overlap: if he and his friends sold their Valheim items through a digital in-game market, they'd be able to live without them. None of the incentives for selling those goods exist in any capacity.

That's because the value of those in-game goods is mostly sentimental. The sense of personal ownership that came from building the base, the satisfaction of slaying monsters to craft items—that's what gives those items value. Their rarity or difficulty to acquire is only one component of the equation. If in-game items aren't really worth that much to someone else—how can you build a functioning economy on top of them?

You can appreciate that a renowned science fiction author may have opinions on the book marketplace. After running through the magic bean comparison, he pivoted to talking about used books.

For most book lovers, a used book represents a love for the story in its pages, or a treasured memory of reading it when in school or at a certain time of their lives. Putting used books on the shelf is an acknowledgement of their value, and for a number of reasons, that value might be made manifest if you decided to sell it to a used book dealer.

Here Stephenson pivoted to harangue a certain section of the used book market: those selling on the basis of artificial scarcity of aesthetics (think booksellers who sell books to be displayed when arranged by color of cover, or sold with paper wrappings on them for a monochromatic choice). These vendors aren't selling a product anchored on the words in the page, they're selling books based on how someone might react to seeing them on a shelf.

Stephenson described this model as being totally disconnected from the world of the book market—and argued if it were to swallow the entire book business, it would create volatility like the kind that sent cryptocurrencies crashing in 2022.

And though volatility is good for get-rich-quick types or scammers, it's not good for sustainable online economies. And for this metaverse company co-founder, the sustainability of online worlds trumps the need for anyone to profit from the sale of digital goods.

When Stephenson and his colleagues took Lamina1 out of stealth mode, he told cryptocurrency outlet Decyrpt that he was a latecomer to the crypto field, but that he imagined something like it to be part of the online world he envisioned in Snow Crash.

"I think it's implicit in Snow Crash that none of what you're seeing there could really exist as described without some kind of decentralized payment system," Stephenson told the outlet in 2022. "There's no, like, one big bank that is sitting there processing all of those zillions of transactions."

But if the cryptocurrency world took Stephenson's arrival in the scene as a blessing, a talk like this definitely indicates he's not fixated on pumping up the value of a digital good. He closed out his talk by referring back to his treasures in Valheim, or the real purpose behind sellable in-game items in in World of Warcraft.

"Most people play Warcraft for the joy of it, and for the experiences they have with their friends and enemies," he mused. "They're not particularly eager to liquidate their inventories of virtual goods because the magic swords in those inventories have utility, as well as intangible qualities—the memories associated with pride and achievement."

At some point in the future there may be good reason to have digital in-game goods be as easily sellable as our real physical stuff is. But "stuff" only has value if people give them value.

"It's not just the currency that sets the value of the goods. It's the goods in the aggregate that set the value of the currency."

And that makes the rest of Stephenson's thought experiment a familiar one who's ever sat down and wearily heard the pitches from the crypto crowd: if a digital world or game isn't fun or compelling on its own, why should anyone care what kind of database it uses to let you buy and sell in-game goods?

Focus on the intrinsic value of these experiences, Stephenson said, and you'll be better off than trying to convince the world that a digital gun or hat has real financial value.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like