Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

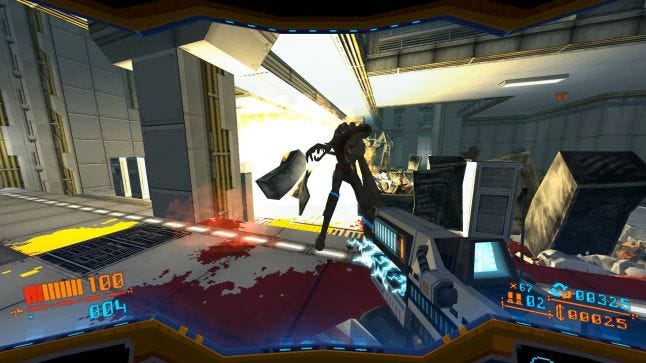

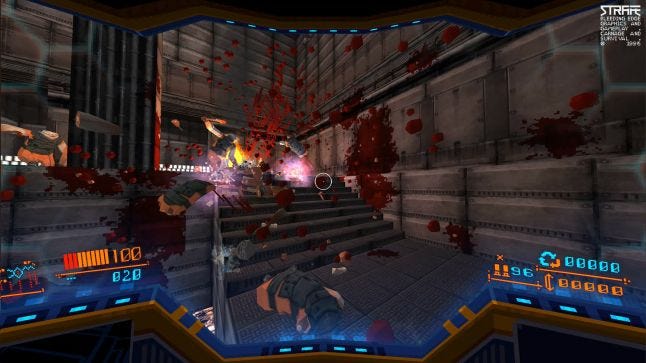

Pixel Titans' new game Strafe looks like a retro shooter straight out of 1996. But beneath the chunky low-poly graphics, the game is a unique and original synthesis of classic game styles and mechanics.

Pixel Titans' new game Strafe wears its inspirations on its sleeve. It hearkens back to the mid-1990s era when PC game fans were racing (and strafing) around in cool shooters like Doom and Quake, and store shelves were full of knock offs of Doom or Quake, and eager young modders dreamed of becoming a game impresario and driving their own cherry red Ferraris to their palatial studio offices.

But beneath the chunky low-poly graphics, Strafe is a unique and original synthesis of classic game styles and mechanics. And it's not simply drawing from old school shooters.

Director Thom Glunt was kind enough to to fill in the blanks for me, outlining the games that inspired five key design choices that Pixel Titans made.

It was important for Glunt to always be motivating players to stay on the move in Strafe, and impart the feeling of skillfully weaving through a firefight, dancing out of the way of attacks and dealing death from all sides. He fought to capture that thrilling sensation from the best FPSs of the ‘90s, of being fully in control of when or if you took damage.

“It feels great in Doom when you dodge an imp’s fireball,” Glunt says, “and it feels bad when a sergeant blasts you with his shotgun with no visible element to dodge. We found projectiles made us feel more responsible for the damage we took, where as it was easier for players to blame the game with hit-scan enemies. So we decided to make all of our ranged enemies use visible projectiles.”

“Some of the most enjoyable memories of gaming I have are tied to secrets," says Glunt. "Doom, Tony Hawk Pro Skater 2, Postal 2, Duke Nukem 3D, Tomb Raider and Wolfenstein 3D all have great secrets that deepened my appreciation for them and created a sense of wonder."

"I’ve had great moments with my friends talking about them and at times I was able to show off the secret and feel cool. We wanted to create these memories for new players, and spent a significant part of development on secrets.”

Poorly designed linear levels can feel cramped and confined, or like they’re railroading a player along a narrow, claustrophobic path. One of the easiest and most effective ways to add depth to a linear design to litter it with side areas, secret chambers, and hidden collectibles.

These sorts of diversions also increase the likelihood of players spending additional time in your level, appreciating the assets you painstakingly created instead of blasting past them en route to the next set piece or firefight. And secrets add a sense of exploration and discovery to a genre that’s more prominently about combat.

“Strafe is a Roguelike, and from day one we wanted to create a repayable and randomized experience," says Glunt. "But I knew that purely procedural levels would never feel good. The levels need a sense of flow and verticality, They need to have cool secrets and a variety of paths for combat to play out in. So I took inspiration from elements of Spelunky’s approach to generation."

"When designing the bank of modules for Strafe, we created a range of rooms that would play like small multiplayer maps, and we connected them via nodes instead of designing on a grid. This allowed the levels to take interesting shapes and feel more unique.”

Handcrafting the modular pieces of the procedurally generated levels allowed Glunt to create specific context for each area, making them feel bespoke and distinct. It also allowed his team to shape each encounter in specific ways, and ensure that there was an appropriate verticality to areas that made them feel more open and expansive than corridors or boxy rooms.

It let them control the flow of combat and gameplay in specific ways and allow enemy encounters to unfold in specific ways (for instance, introducing groups of enemies to a fight in staggered waves, or stringing them out according to the player’s progress). It also allowed the developers to build rooms to surprise or ambush players in ways procedural generation couldn’t accommodate.

One of the most most fundamental and oft-imitated building blocks of those ‘90s shooters was how enemy encounters were structured like combat puzzles. Just think of Quake's gremlins and fiends and zombies. And Quake's bosses, like Armagon, or Shub-Niggurath, or High Priest, or, or ... now I want to go play Quake.

Dealing with each situation necessitated a series of decisions about which weapons you’d deploy, how and where you’d maneuver, and when you’d trigger certain opponents, always striving to maintain a manageable number of alert enemies. And most importantly, it involved being able to quickly and accurately assess an enemy’s abilities, movement speed/patterns, and threat level.

“We subscribed to the thought that each enemy should be designed with purpose, to fill a hole in the gameplay," says Glunt. "Enemies follow a distinct and predictable set of rules that the player can learn and then use against them.We have enemies that make you watch your back, attack at close range, attack from a distance. Enemies that can stomp you from above or switch between 2 behaviors. The pairing of these enemies creates a variety of different combat scenarios that are fun to interact with.”

Glunt says that one of the most important lessons he took from a study of those early shooters, and from seeing peers and fans react to Strafe as it came together, was that imitating them too closely was risky, and straying too far from the template they established was risky.

At the same time, it was clear that it would be impossible to please everyone, particularly an audience as demanding as classic FPS fans. The team had to accept that it was impossible to please everyone, or make the perfect old school shooter that each player saw in their mind's eye.

“There are a small group of players that get very upset that we have the audacity to try something new with the classic shooter formula," says Glunt. "And there’s another group that doesn’t know the genre well enough to know what’s different. We love those games with so much passion that we spent our youth modding them, and made a game that’s an homage to them. But those games weren’t perfect. Even if we can’t improve on them, even if we bring nothing to the table, we all need to realize that no game is perfect. There is always something that someone can critique, even our beloved classic shooters.”

In the end, it’s about establishing a vision and standing by it. “I don’t think you should ever put something in your game without having a strong reason it should be there," he says, "even if no one else gets why.”

You May Also Like