Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A veteran game designer reveals common mistakes and misunderstandings in the profession, and ways to try and improve the craft.

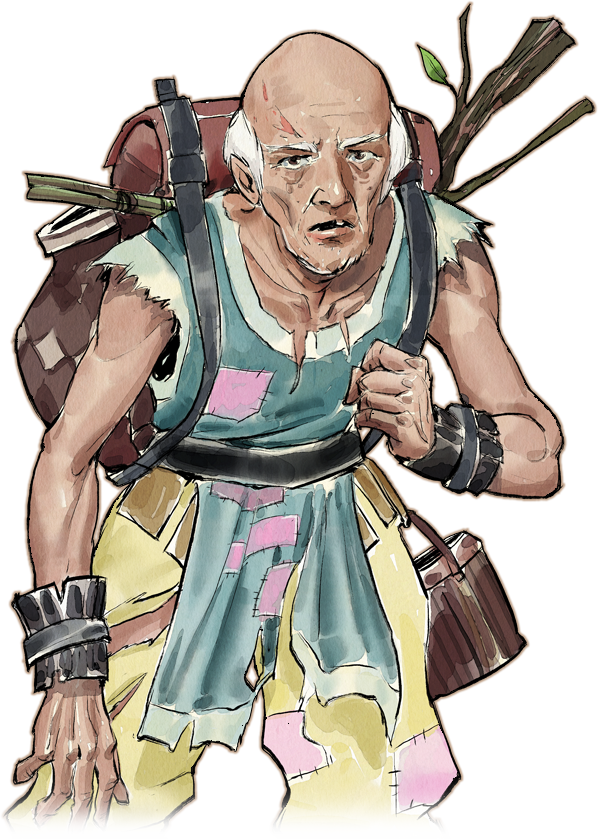

Tanya X. Short is the Captain of Kitfox Games. All illustrations are characters from Moon Hunters currently in development.

Game designers have a pretty great job. By designing systems, levels, rules, features, A.I., items, or any number of other game components, we make the game “fun”.

I’ve worked as an A.I. designer and level designer on big MMOs (Age of Conan and The Secret World), a feature designer on a Facebook game (Fashion Week Live), and now I’m the everything-designer for my own little studio (Moon Hunters, Shattered Planet)... not to mention a bunch of little non-commercial games and mods I've made on my own. In the past 9 years or so of practicing design, I’ve messed it up in all of the following ways at some point or another.

Here are five of the most troublesome yet common ways that we designers screw things up for ourselves, our teams, and our projects.

Terrible Designer Habit 1: Don't Take Feedback

We all know a designer who isn't interested in others' opinions, experiences, or suggestions. Whenever someone has a possible criticism, in the worst case, they jump like a goalie to defend their amazing creation and explain why the interloper's comments are not helpful, not possible, or just wouldn't work.

In the “best” case, this designer pretends to take feedback but allows it to slide off like water from a duck. They might even smile and appear to agree... yet somehow nobody else's ideas ever make it into their part of the game. Some combination of ego, defiance disorder, and insecurity means that only they (or, in some cases, their supervisor) have insight they trust.

This kind of terrible designer might do great work, or she may not. But chances are, the quality of their work will improve only slowly, because they have to learn everything hands-on rather than being able to absorb knowledge from others while in the thick of game development. Our closed-mindedness prevents us from seeing the true potential of our work... and makes our team (or even just friends and supporters) distance themselves from us in the meantime.

When did you last get use an idea or suggestion that wasn't yours?

Terrible Designer Habit 2: Use All the Feedback

Once you've gotten into the habit of taking others' suggestions, it can be hard to know when to stop! This is especially true for designers that are outside their comfort zone – whether we're new to design or new to the genre, platform, or industry, it's common to discount our own instincts and instead follow whatever the last person suggested.

It turns into a more insidious design-by-committee, because it all happens inside one person's head. From the outside, the only thing that's clearly amiss is that their work is inconsistent and lacks focus. You're doing terrible work, and other than months of pattern-observation, only you can really see why.

Luckily, this problem is usually short-lived, because the only thing more painful for a creator than taking criticism is taking criticism for creations that aren't really yours. After a year or two of this, it's common for a designer to unfortunately stop taking all feedback (see Terrible Designer Habit 1).

Bad feedback doesn't even necessarily have to come from reliable sources. All you need is a touch of insecurity and you'll be losing your focus in a heartbeat. At E3, I witnessed an indie dev deal with his first round of Youtube comments. Unsurprisingly, not all of the comments were positive. This dev is extremely smart and talented, but briefly, he lost his guiding purpose, and started talking about taking the game in many different directions. I'm glad he has since sorted out his feelings so he can make a clear decision, but many less strong-willed creators could have been mired for years.

Do you have a clear system to guide when to use (and not use) others' suggestions?

(P.S. Of course, you could just not read the comments. Especially for your mental health. Especially on YouTube. Or you could ask someone else to glance them over for you and filter out the ... less constructive bits.)

Terrible Designer Habit 3: Be Jaded

It's no coincidence that we use the word 'veteran' to describe more experienced game designers. This industry crunches people, burns them out, lays them off, and getting through even one game launch can be hellish. Devs wear the scars of the projects they've survived.

So it's fairly common for experienced devs (including designers) to be cynical and jaded. We've seen what happens to optimists and dreamers. You believe in that initial launch date? Ha! You think the company mission statement matters? You think your contributions can really change anything about the game? Double-ha! Everything is doomed, kiddo, because this is the reality of the games industry.

In fact, when management's out of the room, jaded cynicism is such a common marker of senior devs, canny juniors may emulate this behaviour. We wipe the stars out of our eyes willfully, snarking and doubting and mocking anything that might end up disappointing us, at least outwardly. I think designers are doubly prone to cynicism because we're often the most excitable dreamers on the team, and therefore most quickly find out that even on a well-run project, many extremely good ideas and suggestions will be left on the cutting-room floor.

But in a designer, being jaded is terrible behaviour. Designers generally work across multiple disciplines, collaborating with artists and programmers to ensure that their creations can function and function well. Thus, unlike a grumbling render coder or treasonous concept artist, it's extremely likely that a designer's (even insincerely) low morale will contagiously infect multiple teams.

How do your teammates feel about the project when you're around? Ideally, designers should be a relief to talk to, increasing the productivity of all they come into contact with. Maybe it's not in your nature to be a cheerleader, but at the very least, be aware of how your behaviour could be dragging down the entire project.

Terrible Designer Habit 4: Only Design for Yourself

“It just doesn't feel right.”

When faced with a wall of feedback, and knowing you really should use some and reject others, the natural instinct is to turn inwards and ask your 'gut' what the right call is. After all, designers are avid gamers – we play and analyze all kinds of games, and have done so for years. In the end, aren't we the experts on our own design?

The problem here is that many games aren't made for you. If you generally prefer exploring, some games are about base-building, and vice versa. If you prefer competition, some games are about collaboration, and vice versa. And even if you are very rigorous about acquiring a taste for games outside your natural Motivation spectrum, some games simply aren't made for avid gamers. Yet all games need a good game design.

I found this out the hard way as Lead Designer on Fashion Week Live, a multi-million dollar Facebook game with an illustrious international brand, targeting fashion enthusiasts. I had never subscribed to a fashion magazine in my life, and the training to understand the culture was enormous. I flailed and struggled and ruined things before realizing my usual 'gut instinct' wouldn't help here. I needed logic. I needed skill.

No matter what game you're making, if you intend to show it to anyone else at all (god forbid sell it), you are not the sole audience. Every successful artist knows this – yes, even the lone wolves and “auteurs”. Phil Fish has gone on record recommending all indie developers playtest their games (with humility) regularly, after watching strangers interact with Fez at events. Alexander Bruce famously developed Antichamber for years by playtesting at events. There is a big fat spectrum of possibilities in-between “designing for everyone” and “designing only for yourself”.

Imagine I made a game JUST for me. A game that you could only enjoy and really "get" if you were a 30+-year-old white female English Literature majors from 29 Palms California who'd worked in games as a designer for 10+ years. Even my mother would probably have trouble pretending to enjoy the result.

Maybe you're more generic than I am; maybe you have nothing particular and defining about your tastes and impulses. But I suspect you are just as unique, if not more.

As creative people, most designers 1) dread the idea of chasing some “target audience demographic” and 2) want to make a game we would enjoy playing, assuming we hadn't already spent thousands of hours of our lives making it. Yet both of those desires happily co-exist with an interest in the players' experience.

We are creating only half the game – the player creates the other half.

The trick to recognizing good feedback while turning others down, especially when in an unfamiliar field, is actually also the answer to how to avoid designing solely for yourself.

Designers must define and doggedly pursue a particular user experience. In Moon Hunters, that's (to give the highest-level summary) “to live the mythology of an ancient hero” -- we add and refine functionality to improve that vision and its buttressing pillars. It is the guide by which features are created or cut, not by some vague flutter in my stomach.

Terrible Designer Sign 5: Be (only) a Daydreamer

This is probably going to make some people angry, but in my experience, it's true.

It feels great to coast on a high tide of “what ifs” and “wouldn’t it be cool”s. It can be tempting to just write down all of those thousands of exciting ideas. Game designers tend to be very creative people, and on any given day we’re each overflowing with ways to improve the game we’re working on.

If you’re working mostly on design documents, you’re probably really inspiring to be around. You’re excitable, and maybe even charismatic, persuading others that your ideas are worth implementing. They might believe you. But you might still be terrible.

The problem is that writing down an idea can be much more fun (and immediately satisfying) than actually implementing a feature. And if you never actively work to create things in the game – whether it’s characters, systems, dialogues, encounters, levels – you may be adding difficulty to someone else's work without realizing it. A designer who hasn’t worked in the project editor can’t understand the implications of their own designs.

When did you last implement something?

Was it good enough to be in the final game?

If these questions scare you, it might be because it’s been a long time since you had the technical training to do so. If you think you're “above” that, you might be within your rights (many Lead Designers don't “get their hands dirty”), but you are likely also steadily becoming worse at design. Don't be embarrassed or prideful -- just ask someone to show you what you've been missing out on while you vacationed on Document Island.

At IBM, they have the practice of “reverse-mentoring”. Regularly, senior or even executive employees are trained by junior employees, ensuring they are well-versed on the latest tech, trends, and company culture. Senior or lead-level game designers frequently fall behind as they move into more communication-based roles, but an investment into reverse-mentoring seems prudent for just about any large design team.

Summary

In short, the worst and most common design flaws can be overcome by:

Taking feedback

Being confident in your chosen direction

Staying positive

Designing towards a specific experience, not just for yourself

Understanding how to implement your designs

You might notice that many of these problems are based in extremes and solved in moderation. Daydreaming is great, when it doesn't steer the design past reality. Feedback is great, except when taken in too little or too great amounts. Your instinct will serve you well, but cannot make 100% of your decisions. As always, your own understanding of your project and its needs will outstrip any general statement.

If you recognize that sometimes you're a bad designer, welcome to the club! None of us are perfect. But the best of us strive to always improve, to keep learning, and to make a better game than we ever have before.

If you have any additional advice for designers (junior OR senior), chime in below or tweet at me anytime. I know those of you who disagree will already be on the case!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like