Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Foreshadowing is a valuable tool that every game maker should have in their arsenal, so we reached out to some devs who know their stuff for tips and examples of games that do it well.

Great foreshadowing is a win-win — it makes players feel smart and developers seem smart. It adds depth without any painful exposition, and it can add impact to big moments or lend a hidden helping hand to players using new mechanics in pressure-filled situations without explicit tutorializing.

Foreshadowing is more than a plot device. It's a valuable technique that every developer should have in their arsenal, to use in level design, dialogue, audio, cinematics, and every other element of a player's experience. But it's easier to do it badly than to do it well, so we reached out to some designers who know their stuff for examples.

Here are seven games that make exceptional use of foreshadowing, in any of its myriad forms, plus some extras that are also worth studying further.

Opaque Space game design lead Jennifer Scheurle loves the foreshadowing in Alice: Madness Returns, which expertly adapts the 3D camera lookahead lessons of the likes of Mario 64 to point the way forward. Scheurle notes that does this mainly by using level fly-throughs and elevated points that allow the player to see everything that lies ahead.

These make it possible for the player to plan out much of their movement and to anticipate where they might encounter combat or other trials. They prime the player for action, constantly building anticipation and in the process establishing a powerful feedback loop where each reward shows promise of the next one while also moving the player closer to the ultimate goal that's so often visible in the distance.

TAKEAWAY: Showing the player the path ahead need not ruin the surprise. In any case, it motivates them to keep going and helps them to plan and mentally prepare for the trials to come.

Robot Invader co-founder/CEO and Oculus developer relations rep Chris Pruett suggests Virginia as a compelling example of narrative and thematic foreshadowing. Set up as a mystery thriller and filled with movie-style hard cuts to advance time and juxtapose events, it leans heavily on its visual language. And Pruett thinks it's worth looking at how it uses foreshadowing in character dream sequences and other "what if" scenes.

"The game builds a visual motif to represent these sequences," he explains, "[namely] a door with a red glow behind it, and then uses that same visual style to build tension later in the game. At one point the protagonist finds herself crawling through a drain pipe when all of a sudden that same red light appears at the other side, and we understand that this signals an equivalence between the unknown end of the pipe and the mysteriously locked red dream door."

Eventually, continues Pruett, there's a "what if" sequence that's been heavily foreshadowed and itself represents a possible future to pursue. "This is really just well-executed storytelling mechanics, but it’s enabled in this title by the interesting approach to abrupt scene changes that the game employs."

TAKEAWAY: If used well, visual metaphor is a powerful way to add depth to a game's story and world, and if it's well integrated within a game's broader visual language then the metaphor — and any foreshadowing that might be wrapped in its use — can be more easily layered into the narrative.

The entire Silent Hill series is renowned for a sense of dread and foreboding, much of which is created through a combination of metaphorical language (in the environments, mechanics, and narrative) and atmospheric graphics and sound design. But these games also have a fine knack for hinting at future plot points through glimpses of events or encounters with objects that are more significant than they appear.

Silent Hill 2 and 4 do this especially well. In Silent Hill 2, a game renowned for its provocative taboo-grappling storyline, the very first scene foreshadows (one of) the ending(s) — which is further hinted at by numerous other events and metaphors throughout the game. The player can find the name of their character on a grave, for instance, while exploring an underground maze that's often interpreted to be a physical manifestation of the fears and repressed memories of the game's three principle characters.

Silent Hill 4, Pruett notes, is inferior as a game but perhaps much more important to study, as its foreshadowing tricks have not been as widely copied or analyzed. "The arc of the story involves the protagonist meeting people just before they are killed by a serial killer," says Pruett, "and eventually realizing that he has been targeted as the final victim."

Pruett sees Silent Hill 4 as a kind of collection of experiments in multiple types of foreshadowing. "My favorite trick from this game is the way the camera will twist as the player approaches a door in third person," he says. "It’s a simple technique but it serves to heighten the tension involved with opening the door itself."

TAKEAWAY: Visual metaphor can also reveal insights into the inner workings of a character's mind before their actions or words do, and even present personal truths that they themselves are yet to discover. Also, simple things like camera movement or audio cues can easily and effectively build tension that foreshadows bad tidings dead ahead.

Warner Brothers Games director of cinematics Marty Stoltz points to the final scene of the I Know You mission in Red Dead Redemption as a great plot foreshadowing moment. The mission involves a mysterious man who claims to have known protagonist John Marston years ago, and who seems to know Marston very well even though Marston has no recollection of him. The man has two tasks he'd like the player to complete, both moral dilemmas, and then after these are done — regardless of the moral choices the player makes — he admits to not remembering his own name but draws attention to the spot he's standing in and says he's doing his "accounts".

Marston "will be responsible" for his actions, he hints, before again drawing attention to the spot that at the end of the game becomes Marston's burial site and walking away as an angry Marston's bullets pass harmlessly through him.

"This allows the viewer to put two and two together," says Stoltz, giving them the reward of saying 'aahhhh I get it'. The fact that you try to shoot at him and nothing happens softens the viewer up to [the idea that] something funny is going on."

TAKEAWAY: While this technique should be used sparingly in most games, seemingly unexplainable events and interactions can create intrigue that magnifies the impact of a game's ending or strengthens a future reward — provided the player connects the dots between two connected but far-apart moments in their experience.

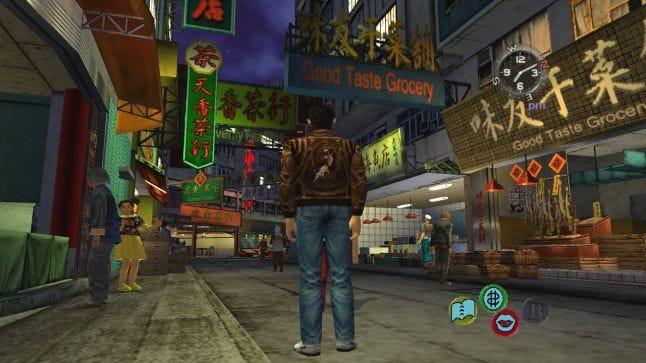

Pruett sees a synchronicity in Shenmue 2's mechanical foreshadowing, which uses mundane mini-game sequences (catch tree leaves, carry a pile of books, practice martial arts techniques, etc) early in the game to introduce control systems that return in more complex forms late in the game. It goes beyond the standard design conceit of tutorial -> pattern -> variant, Pruett explains, in the way this early experience ties into the progression of both narrative and mechanics.

"I think the linking of the narrative progression to the progression of mechanics in Shenmue 2 is exceptional," he says, "and it foreshadows much of the challenge to come before the story has really landed on a clear course."

TAKEAWAY: Tutorials and mini-games can have a role beyond teaching and reinforcing mechanics or control systems; they can plant seeds for future plot developments and for new game mechanics that have similar logistics but that occur in a different (though related) context.

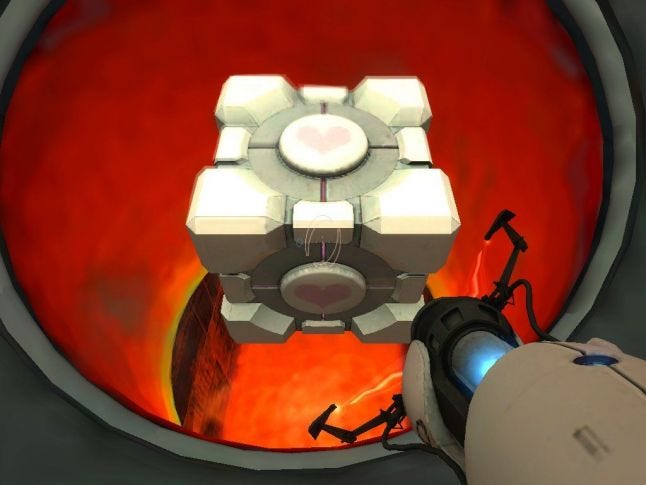

Portal remains one of the best examples of how to teach players new mechanics organically through world design, and it uses many of the same techniques to foreshadow its latter stages. At one point, for instance, antagonist GLaDOS announces that "when testing is complete you will be... missed." Later, in a more overt hint at the player's intended fate, she states "The enrichment center is required to remind you that you will be baked, and then there will be cake."

Other announcements and wall markings make clear that the promised reward of cake at the end of the testing procedure is not what it's made out to be, while GLaDOS's repeated malfunctions foreshadow her later psychotic break, and there's even an allusion to the fact that — as learned in Portal 2 — the Aperture Science facility extends beyond the test chambers. And in one particularly memorable scene the player is forced to incinerate — to "euthanize" — the "faithful" companion cube that had theretofore been depicted as Chell's friend. Brutally, and subtly, the game here informs the player that Chell is ultimately disposable, a point reinforced just a short time later for players who read the scribbles on a wall left by another test subject.

TAKEAWAY: Foreshadowing can be used to prime the player for a false outcome while subtly indicating the true one, and it can set up a mystery or promise a big payoff that drives the player onward.

Scheurle points out that the Zelda series is "super notorious" for using mini-bosses to foreshadow the weapons, patterns, and techniques of final dungeon bosses. More broadly, the Zelda games are widely recognized for their brilliance at introducing players to ideas and mechanics before players actually have the ability to use them.

Often imitated but seldom surpassed, Zelda's foreshadowing techniques largely serve to increase the reward and depth of the experience. They succeed by following several best practices. It's always clear, for instance, when a problem is insurmountable with the player's current abilities and items, and the mechanics or narrative beats that get foreshadowed are seldom far off into the future — indeed, most are contained within the same dungeon and players may immediately recognize some past places they've seen where the new ability/item can be used.

This has many benefits, as Why Not Games programmer/designer Nikhil Murthy noted in a mechanical foreshadowing blog post — especially in open-ended games. It teases at the game's depth (without piling on too much complexity too soon), builds anticipation, improves the playability and believability of the experience, and makes rewards more impactful (because it creates an "a-ha!" moment and gives the reward a greater sense of value).

TAKEAWAY: Good foreshadowing builds anticipation and increases depth, but it also eases the cognitive load of a new mechanic/system to learn or of a big plot twist or location change.

You could think of great foreshadowing as being kind of like giving players an inside track on where the game is headed, only without actually telling them that they have this knowledge or what they can do with it. It's a way to let them in behind the scenes on a subconscious level so that difficulty spikes are more manageable or big narrative moments feel more remarkable — more meaningful, because, whether they realize it at the time or not, the player has previous insight into the how or the why or the what of those moments.

The very best examples of foreshadowing tend to be things that only become apparent as foreshadowing after the fact, once the thing foreshadowed has been revealed — as in that memorable Red Dead Redemption example or Portal's companion cube death or Silent Hill 4 and BioShock Infinite's very first scenes. But that's not to discount the value of well-executed mechanical foreshadowing, as in the Zelda games and in Shenmue 2 and some Mario and Mega Man games.

When it really comes down to it, foreshadowing is about conveying important information to a player through implicit rather than explicit means. As such, it's best used as an early warning system — a subtle indicator but never a direct explanation of what's to come.

Other compelling examples of foreshadowing that might be worth a closer look include Arkham Knight's use of the Frank Sinatra song "Under My Skin" while the Joker's body gets cremated, Half-Life 2's Citadel — which looms out from the horizon throughout the early stages of the game — and a player's first encounters with water and other civilizations in the Civilization series, both of which hint at a much greater world to explore and contend with. There's also the locked doors many games offer before presenting a key (though you should watch for overuse or misuse of this trick) and Alan Wake's use of passages or phrases read in the protagonist's novel that presage game events soon to happen.

Also, Jennifer Scheurle took the question to Twitter when I asked her for examples and was met with dozens of additional responses that are well worth perusing for yet more ideas and insights for how to work foreshadowing into a game's design.

Thanks to Jennifer Scheurle, Marty Stoltz, and Chris Pruett for their help putting this list together.

You May Also Like