Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The Japanese role-playing game is a surprisingly important genre for developers to study - both in terms of gameplay and storytelling, and Gamasutra presents an 'Essential 20' explaining and chronicling the top JRPGs of all-time.

[The Japanese role-playing game is a surprisingly important genre for developers to study - both in terms of gameplay and storytelling, and Gamasutra presents an 'Essential 20' explaining and chronicling the top JRPGs of all-time.]

The gap between Western and Japanese RPGs is so huge that they sometimes don't even seem like they belong in the same genre. Western RPGs usually concentrate on open-ended gameplay, with a "go anywhere, do anything" mentality.

Japanese RPGs concentrate on narrative and battle systems, being more eager to tell a story than let the gamer play a role. However, Japanese RPGs didn't just appear out of nowhere -- as their roots lie heavily in early American computer RPGs of the 80s.

Two of the most popular games back in the day were Ultima and Wizardry. Although all had followings amongst hardcore Japanese gamers, they were a little bit too uninviting for your average console owners, whose ages skewed a bit younger. Yuji Horii, a developer at Enix, decided to take on an interesting experiment.

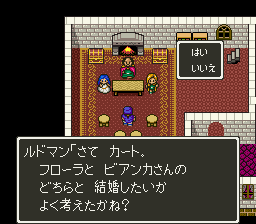

By combing the overhead exploration aspects of Ultima (the third and fourth games, specifically) and the first person, menu-based battle system of Wizardry, a new game was born: Dragon Quest. Released for the Nintendo Famicom in 1986, the game became a phenomenon, and went on to inspire dozens of clones. Most of these are best left forgotten, but it did inspire two more notable franchises: Square's Final Fantasy and Sega's Phantasy Star.

Meanwhile, in America, it wasn't until 1989 that Nintendo translated the game for English speaking audiences, redubbing it Dragon Warrior. Despite the huge amount of effort put into the localization, the subpar graphics and stodgy interface failed to win over many gamers.

Throughout the rest of the 8 and 16-bit eras, RPGs in America -- and especially Europe -- were relative rarities. While Square continued to translate most of its better games for America, most publishers had left the market, with only sporadic releases from the likes of Capcom, Sega, Working Designs, and a handful of others.

It wasn't until Final Fantasy VII for the PlayStation, with its flashy full motion cutscenes, that Japanese RPGs truly obtained worldwide popularity.

Since then, a vast majority of JRPGs have been translated into English, whether they're contemporary releases, remakes of old titles or even fan-translated ROMs for play on emulators.

As of 2008, the Japanese RPG has become a subject of scorn for many Western critics, deriding it for its conventions -- slow, menu based combat, random battles, overreliance on narrative -- and for its failure to evolve. In spite of this, there are still many fans of the genre, who continue to enjoy them for their interesting plots, characters, and battle systems.

This is a list of twenty of the best JRPGs of all time -- well, an attempt, anyway. Each of these has been selected for excelling in some significant way, whether it's through compelling narrative devices or intriguing gameplay mechanics.

To avoid redundancies, only the best installment of a franchise will be chosen as a representative. The exception to this rule includes the Final Fantasy games, many of which are so vastly different from each other that they can barely be recognized as part of the same series, outside of the name.

It's worth bearing in mind that there are technically a few different subgenres of the Japanese RPG. These include action-RPGs like Ys, Kingdom Hearts, Secret of Mana, and (arguably) The Legend of Zelda.

There are also strategy RPGs, like Fire Emblem, Final Fantasy Tactics, Disgaea, Shining Force, and the like. There are also a handful of Japanese-developed online RPGs, like Phantasy Star Online and Final Fantasy XI. For the sake of focus, these types of games will be excluded from the list.

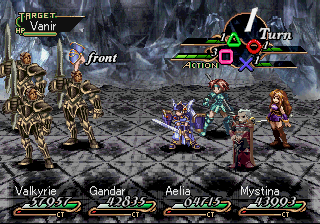

Valkyrie Profile

Developer: tri-Ace

Publisher: Enix America (2000, PS1)

In most RPGs, it's your job to stop the end of the world. In Valkyrie Profile, it's your job to start it. Ragnarok, the end of the world as defined in Norse mythology, is just around the corner, and the Good Guys in the heavens are in desperate need of souls to fight in the resulting war against the Bad Guys in the underworld.

There's a catch to recruiting these soldiers, dubbed Einherjar -- they need to be dead. As a valkyrie named Lenneth, you fly through the world of mortals, listening to their cries for help, and rushing to the moment of their death.

With each character, you get a short glimpse of their story -- as lives are shattered, happy couples are torn apart, and heroes become martyrs. Amidst all of this is Lenneth, who seems to have a past in the human world that she's only barely conscious of.

There are roughly two dozen characters to recruit -- some fully fleshed out, others barely touched on -- but their souls are not yet ready to fight for the gods. You need to train them by taking them into dungeons, building both their battle skills and their spiritual fortitude. All of these dungeons are side-scrolling stages, filled with puzzles, traps, and of course, numerous enemies.

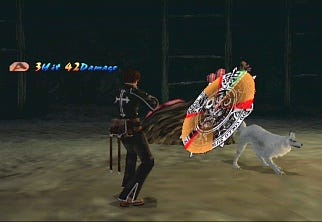

The battle system is a strange beast, with actions for each of the four party members assigned to a face button. Each character has a number of attacks, each with unique speed and strength -- timing the button presses to create combos and juggle enemies is the key to executing impressive special attacks and overpowering foes.

Tri-Ace, creators of the Star Ocean series, has a knack for creating exciting, visceral battle systems that feel like action games, even though they're still heavily rooted in role playing conventions. The soundtrack, provided by prog rock virtuoso Motoi Sakuraba, is also one of his best works, delivering both pounding, intense battle themes and dreamy, melancholy ballads. In other words, it packs a punch that few RPGs can counter.

Tri-Ace, creators of the Star Ocean series, has a knack for creating exciting, visceral battle systems that feel like action games, even though they're still heavily rooted in role playing conventions. The soundtrack, provided by prog rock virtuoso Motoi Sakuraba, is also one of his best works, delivering both pounding, intense battle themes and dreamy, melancholy ballads. In other words, it packs a punch that few RPGs can counter.

Tri-Ace also has a reputation for being a little bit too obtuse, which undoubtedly attracts the hardcore RPG fan but tends to confuse everyone else. The entire game is divided into eight chapters. In turn, each chapter is divided into a number of segments.

Every time you visit a town or a dungeon, it eats up one time segment, therefore limiting the amount of places you can visit and the events you can witness. It becomes important to budget your time, but the game is so loosely designed that it's easy to miss important things if you're not paying attention.

Similarly, at the end of each chapter, you need to send off some of your warriors to the heavens, permanently removing them from your party. You're given vague hints about the requirements, but you can never be sure that you're doing it properly -- especially when it could potentially leave you with an underpowered squad.

There are three difficulty levels to ease newcomers into the unique flow of Valkyrie Profile, but playing on easy mode robs the player of half of the playable characters, and limits access to certain areas of the game. It's meant to provide replay value, but comes off as withholding to all but the bravest of gamers.

Still, the concept alone is enough to life Valkyrie Profile to classic status. The sequel, released a whole generation later for the PlayStation 2, strangely ditches the structure in favor of a more conventional approach.

There are still 2D side scrolling areas, this time rendered with some of the most beautiful real time polygonal graphics on the system, but the Einherjar are faceless, and their recruitment now plays a distant fiddle to core narrative.

The story itself is unlikely to interest those who weren't invested in the main plot of the original -- which was somewhat obscure to begin with -- but the battle system has been greatly expanded to allow the party to move around the battlefield, providing a substantial amount of tactical depth that was missing from the original. For this reason, it's still a remarkable title, but the innovative approach of the original game makes it shine brighter.

Final Fantasy IV, VI & VII

Developer: Square

Publisher: SquareSoft (1991, SNES / 1994, SNES) & SCEA (1997, PlayStation)

If it seems like it's cheating to bunch a handful of games together in one entry... well, it kind of is. There are a number of other Final Fantasy games on this list, but each of them was chosen for some very specific aspect. Final Fantasy IV, VI, and VII are probably the least radical of the modern entries -- and therefore, the least unique -- yet they're considered to be the most beloved entries in the series.

Final Fantasy has always walked the very thin line between "casual" and "hardcore" gaming styles. The idea is that casual gamers will be attracted to the narrative and characters, while the hardcore will find some crazy customization or battle aspect to figure out.

Some of them tilt in one direction more than the others -- Final Fantasy V, VIII and XII offer hardcore gameplay systems, while Final Fantasy X emphasizes story. These three entries -- IV, VI, and VII are the most balanced between the two aspects, which is probably why they're so widely pleasing.

Final Fantasy IV is the epitome of cheesy, melodramatic 16-bit RPGs -- the dialogue is brief, the characters are likable but one-dimensional, nearly half of the game's cast nobly sacrifices themselves, and all but one of them turns up alive and well later in the plot.

The story of the conflicted Cecil and his equally conflicted best friend Kain has all of the basic workings of a Shakespeare drama, even if they're carried out with silly little sprites, whose only methods of emotional expression include spinning, bouncing, and looking at the floor.

Some of the 8-bit RPGs began to emphasize narrative, like Final Fantasy II's war-torn plot or Dragon Quest IV's party of memorable warriors, but Final Fantasy IV weaved everything together brilliantly and set the stage for all future genre entries.

Some of the 8-bit RPGs began to emphasize narrative, like Final Fantasy II's war-torn plot or Dragon Quest IV's party of memorable warriors, but Final Fantasy IV weaved everything together brilliantly and set the stage for all future genre entries.

As such, the advent of the SNES signified not only enhanced graphics and stunning music -- Final Fantasy IV still has one of composer Nobuo Uematsu's best scores -- but the next generation of storytelling as well. The fact that that the DS remake -- released fifteen years after the original -- still stands up to most other portable RPGs is a testament to its lasting power.

Final Fantasy VI was released four years later, with significantly improved graphics. Characters were now twice as big, and potentially twice as expressive. The themes are common, especially throughout the Final Fantasy series -- a rebellion against an evil empire, an outsider with mysterious magical powers, and a sadistic villain that seems to be evil for the vaguest of reasons.

Final Fantasy VI's strengths lie in both its scenario and its characters. It has the largest group of playable characters in a Final Fantasy game, with a total of fourteen party members, including two hidden ones. Their abilities are static, like FFIV and unlike FFV. They're still marginally customizable, through the use of relics and equippable summon monsters called Espers, which modify their stat growth a bit and teach them magic.

Each character's inherent skills are important from a storytelling standpoint, as each of their personalities are reflected in their abilities. Cyan's "Bushido" requires waiting several seconds to charge up attacks, which reflects his persona as patient and stoic warrior. Sabin, while not having a particularly strong personality, is occasionally represented as a bit of a meathead.

As such, his attacks are incredibly powerful, as denoted by his muscular stature -- but they're unpredictable, seeing as how you can't target individual foes, and the success of a move is determined by command motions, the fighting game equivalent of brute force, rather than strategy. Setzer doesn't require much of an explanation -- when you convince him to join your party, his response is basically "Why the hell not?" He's a man on the edge, just like his Slot machine ability, which, if luck isn't on your side, can potentially harm your own party.

This idea of portraying a character through gameplay has been around for ages -- strong characters use physical attacks, frail characters use magic and have low HP, etc. It was also used in the same manner in Final Fantasy IV -- Cecil's life-draining attack as a Dark Knight, which are replaced with healing powers once he becomes a Paladin; Edward's Hide attack showing his cowardice -- but they're much more expanded here, and a quite bit more interesting.

Like Chrono Trigger, Final Fantasy VI's other strength shows through in its remarkably powerful scenario design. Once the game really gets into gear within the first hour or two, the game tosses out a number of memorable events -- the spooky Phantom Train, the introduction of Kefka and his malicious poisoning of Doma Castle, the silly but ultimately impressive opera scene, the assault on the Magitech Factory, Celes' attempted suicide.

Like Chrono Trigger, Final Fantasy VI's other strength shows through in its remarkably powerful scenario design. Once the game really gets into gear within the first hour or two, the game tosses out a number of memorable events -- the spooky Phantom Train, the introduction of Kefka and his malicious poisoning of Doma Castle, the silly but ultimately impressive opera scene, the assault on the Magitech Factory, Celes' attempted suicide.

It's also one of the first RPGs where the bad guy actually wins, enslaving the world and reducing it to a total wasteland. It's also worth pointing to the second half of the game -- where the narrative steps aside and eventually lets you explore the open world. Though disliked by some series fans, it also shines, as a huge number of subquests open up, allowing those suffocated by the linearity of the first half to get a little more breathing room.

And then there's Final Fantasy VII, beloved for its interesting characters and cool cutscenes, hated mostly for being a huge success -- and thus the effect it had on JRPG design. And yet, FFVII rides heavily on the coattails of its predecessor -- a group of rebels banding together to face an oppressive evil, another young girl with ancient, mysterious powers -- but goes so over-the-top that it stands out from the crowd.

The biggest difference is that FFVI was an ensemble cast, with the viewpoint switching around between a handful of major characters. Instead, FFVII focused on the development of Cloud, whose huge, spiky blond hair and exaggerated sword has since became an icon of Japanese excess in the same way that hulking, bald space marine has become stereotypical Western gaming.

Cloud is neither hero nor anti-hero -- as we learn, Cloud is somewhat of a weakling with delusions of grandeur, believing himself to be a world-saving bad guy when he's actually just a dude with some psychological issues. This is one of the first instances of an unreliable narrator in JRPGs, adding something new to the usual "boy meets girl then saves world" formula.

At the time, its impressive cinematics were Final Fantasy VII's selling point. The character development system isn't quite as cool this time around -- the Materia is similar to the Espers from FFVI, except it allows characters to swap skills amongst each other.

At the time, its impressive cinematics were Final Fantasy VII's selling point. The character development system isn't quite as cool this time around -- the Materia is similar to the Espers from FFVI, except it allows characters to swap skills amongst each other.

By removing most of the specialized character skills, it loses some of the narrative appeal of its predecessor, and thus the player tends to pick party members based off who looks the coolest, rather than what they can do. Outside of a few famous scenes -- particular Aeris' murder -- the game is muddled with a subpar localization, another step down from FFVI.

However, the game world has been fleshed out favorably. FFVI's world drew elements from steampunk, but was really just a darker, more detailed variation on the previous games. FFVII's field may just appear to be a 3D rendering the same world map we're used to, but the locations are hugely varied, ranging from the creepy European village of Nibelheim, the Disney World-esque amusement park Golden Saucer, and the traditional Japanese town of Wutai. At the core of this is Midgar, a technological dystopia that borrows heavily from Blade Runner and other classics of science fiction.

It's easy to point fingers at Square Enix for abusing the Final Fantasy VII series with its multiple spin-offs, like the lousy shooter Dirge of Cerberus or the vapid action flick Advent Children.

But the world is so rich and interesting that it actually feels like it has enough depth to explore and expand. The best spinoff -- Crisis Core for the PSP -- draws heavily on the player's nostalgia for Final Fantasy VII, so wandering through Midgar feels like revisiting an old friend. Despite its overbaked tendencies, it still remains compelling, even after the twists have long worn out their appeal.

Xenogears

Developer: Square

Publisher: SquareSoft (1998, PlayStation)

In PR-speak, the word "epic" means "really, really long." That term seems a bit misused, especially when the "60+ hours of gameplay!" can tend to be monotonous grinding and empty wandering. Not so with Xenogears, a sci-fi story it's one of the few JRPGs that could actually qualify as being an epic, just for the astounding amount of detail that's been written into the game world.

As a young villager named Fei Fong Wong, you try to defend your village by climbing into a nearby abandoned mech, only to accidentally destroy the whole place, killing off practically everyone you knew and loved. After being exiled, Fei, like many RPG heroes, learns that his destiny is much more significant than he expected, leading to the discovery of the roles he's played in the origin of his planet and the evolution of humanity.

All of this culminates in a religious conspiracy, bringing into question the act of fighting against God -- which, in the case of Xenogears, is pretty far from the clichéd, bearded deity you might expect. This topic had been touched upon in a handful of other Japanese games, but at the time, it seemed remarkably innovative, and the many plot twists still remain captivating.

Though its creators deny it, Xenogears appears to draw a lot of inspiration from the mid-'90s anime classic Neon Genesis Evangelion. Both involve giant mechs pulling off all crazy stunts. Both have heavy religious and philosophical overtones, sometimes drastically mangling Christian symbolism to unintentionally hilarious effects.

Both are overly wordy, a bit pretentious and occasionally borderline nonsensical. Both are also extraordinarily ambitious, and as a result, both suffered developmental constraints. Evangelion ended its 26-episode run with two avant-garde episodes that barely provided a closure to the plot, and the two movies that followed devolved into more craziness that posed as many questions as were answered.

Xenogears, in the meantime, had the infamous Disc 2. After the first CD is completed, the second CD puts the concept of "player control" out to pasture. Instead, the main characters narrate the story, in dreary, slow moving text, only occasionally allowing the player to explore a dungeon or fight a battle.

Xenogears, in the meantime, had the infamous Disc 2. After the first CD is completed, the second CD puts the concept of "player control" out to pasture. Instead, the main characters narrate the story, in dreary, slow moving text, only occasionally allowing the player to explore a dungeon or fight a battle.

If nothing else, Disc 2 shows how much background story was written into the world of Xenogears, even it couldn't be squeezed into a single game. All one has to do is look at Xenogears Perfect Works, a 300 page behemoth of a guide released in Japan.

Practically every major Square RPG gets at least one "Ultimania" book, which contains statistics, scripts, artwork, screenshots and so forth, but a huge chunk of Perfect Works details the history of the game world, its politics, religion, geography, and science. It's fascinating to see how the entire species evolved into the time frame where the main story takes place, which is a major theme of Xenogears.

The rest of the game is pretty good too, if not particularly innovative. The battles -- which are either fought on foot or inside the mechs -- are generally enjoyable, even if their depth doesn't hold a candle to the story. It's a bit strange that so few RPGs feature mechs (outside of a few strategy games like Front Mission and Super Robot Wars), considering their popularity in Japan, so any opportunity to climb into a giant robot and dish out damage is reason enough to check out Xenogears.

The exploration is a bit clumsy, especially in the dungeons that involve platforming, but the architecture feels more three dimensional than most RPGs of the era. The soundtrack, too, is one of the high points, consisting of both entrancing world music and powerful orchestrations, provided by Yasunori Mituda.

After the Xenogears team went to work on Chrono Cross, a number of members left to form Monolithsoft. Their vision was to create a fully fleshed out version of the Xenogears saga, remaking the series to avoid stepping on Square's copyrights. Titled Xenosaga, it has just as much, if not more, detail than Xenogears, and -- spread across three games -- would practically redefine the concept of "epic" once again.

Still, once again, the plot was simply far too ambitious for its own good, and the number of planned installments was cut down from six to three, compressing the plot even more. It didn't help that the first two games were saddled with terrible pacing issues, plodding cutscenes, and boring battle systems.

It wasn't until the third and final game that Monolithsoft found a happy medium, with snappy fight scenes and less frequent cinematics, but by that point, the plot had already been compromised, and many potential fans had already written it off. Xenogears, even with its long winded text sessions, is still the better game, but for all of its flaws, Xenosaga is still a respectable companion piece.

Chrono Trigger

Developer: Square

Publisher: SquareSoft (1995, SNES)

Nearly fifteen years after its release, longtime JRPG fans still point to Square's Chrono Trigger as one of the best of the best. Although it was hardly a point of interest at its American release, Chrono Trigger resulted from the combined efforts of Hironobu Sakaguchi and Yuji Horii -- in other words, the masters behind Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, the two most popular JRPG series in the world.

By combining Square's talents at storytelling and aesthetic design, along with Horii's skillful scenario design and knack for simplicity, they almost created the perfect game.

One of Dragon Quest's greatest strength is its reliance on tradition. It's also its greatest failing, forcing the development team to keep at variations of the same theme, simply because that's what Dragon Quest is. In essence, Chrono Trigger is essentially a Dragon Quest game that's allowed itself to step outside of the limitations of the series and do something a bit more daring.

For the longest time, Akira Toriyama's character artwork was confined into tiny, little, barely distinguishable sprites -- never clearly visible until after Chrono Trigger. With Square's talented artists, the trio of heroes -- spiky-haired country boy Crono, feisty would-be princess Marle, and bookish scientst Lucca -- came to life in ways that Dragon Quest never had. Koichi Sugiyama is an extremely talented composer, but his music stylings rarely go beyond Western-style symphonic orchestrations.

Here, Final Fantasy composer Nobuo Uematsu is free to rock out with a few contributed tracks, but a bulk of the soundtrack composed by the talented Yasunori Mitsuda, who made his name on this game. Whereas Dragon Quest always felt a bit low budget, Chrono Trigger is one of the most gorgeous looking, gorgeous sounding games on the Super Nintendo.

Certain other elements from Dragon Quest have been carried forward, most notably the existence of a silent protagonist. It also, unfortunately, affects the battle system -- the only method of character customization come in the form of stat enhancing seeds, another carryover from Dragon Quest.

For some reason, the number of playable characters has been cut down to three. At least it implements a battle function called Double and Triple Techs, where two or three party members can combine their magic spells for extra special attacks. In some ways, it's a step down from both Final Fantasy's and Dragon Quest's respective systems, but it's not enough to really matter in the long run.

The DQ series is also known for its snappy scenario design, full of memorable events and NPCs. Chrono Trigger is a nonstop ride through numerous setpieces -- Crono's accidental trip to the past, his subsequent trial and resulting escape, the discovery of Lavos in the post-apocalyptic future, the drunken celebrations in the prehistoric era, the raid on Magus' castle and the lead-up to the fateful battle.

The DQ series is also known for its snappy scenario design, full of memorable events and NPCs. Chrono Trigger is a nonstop ride through numerous setpieces -- Crono's accidental trip to the past, his subsequent trial and resulting escape, the discovery of Lavos in the post-apocalyptic future, the drunken celebrations in the prehistoric era, the raid on Magus' castle and the lead-up to the fateful battle.

Pretty much the entire game is series of climaxes, one after another after another. It's also quite compelling to see how the relatively small game world changes in all of the different time periods. Near the game's end, a handful of subquests really show off how cool it is to amend the mistakes of the past to change the future.

Time travel is such a fertile ground for interesting storytelling that it's a shame few games explore it. Even Horii himself tried it later in Dragon Quest VII, with far less interesting results.

The only real downside of cutting down all the treacle is that the overall quest is pretty short -- one can probably beat it in maybe fifteen hours. To counteract this, Chrono Trigger introduced the New Game+, which allows you to restart the game from scratch but carrying over the stats from when you beat the game.

After a certain point in the plot, you can time travel directly to fight Lavos, and depending where you are in the story, defeating him will reveal over a dozen different endings. All of this helps expand one of the most intriguing stories found in Japanese RPGs.

Shadow Hearts: Covenant

Developer: Nautilus

Publisher: Midway (2004, PS2)

Shadow Hearts is a game of contrasts. On one hand, you have an immensely violent and brooding hero, fighting in a world filled with hellish demons. On the other hand, you have flamboyantly gay shopkeepers, even stranger cast of supporting characters and a real world setting that grossly misinterprets historical figures and events to its whims. The games consist of moments of tragedy intermingled with moments of total ludicrousness.

The first Shadow Hearts -- which was released in American within a week of Final Fantasy X and got totally demolished at retail as a result -- errs a bit too much on the serious side. The third Shadow Hearts, subtitled From the New World, takes place a warped version of 1920s America and conversely errs a bit too much on the wacky side. Sitting beautifully in the middle is Shadow Hearts: Covenant, which balances its tone perfectly.

The game initially focuses on a young German soldier named Karin, who encounters a malicious demon during the occupation of France in World War I. This demon is actually Yuri, the shape-shifting hero of the previous title, who seems to have made an enemy of the Vatican. Yuri and Karin eventually team up and run off, accompanied by a puppeteer who uses his dancing marionette to attack monsters.

Later, you'll be joined a giant wrestler/vampire who will occasionally switch into a his alter-ego, the butterfly-mask wearing "Grand Papillion". As you traipse through war-torn Europe and Japan, you'll run into such historic personalities as Rasputin -- one of the big bad guys, obviously -- all while fighting demons, and occasionally running subquests to find gay porn so you can upgrade your weapons.

This completely twisted worldview is half of what makes Shadow Hearts so instantly memorable. The other half is Yuri, one of the most amusing protagonists seen in an RPG.

He's part brooding anti-hero, the kind popularized by Final Fantasy's Cloud and Squall, but he's also part sarcastic jackass, able to make light of his situations, wherein his predecessors would just go into the corner and brood. It's also amusing that a guy who can transform into dozens of different demons is the straight man amongst a cast of total weirdoes.

The scenario is pretty cool, but Shadow Hearts also deserves commendation for the Judgment Ring system. For years, developers have been trying to answer the question -- how do we make battle scenes more involving than just picking selections from menus? In Shadow Hearts, the Judgment Ring is a dial with portions of the circle marked in green.

The scenario is pretty cool, but Shadow Hearts also deserves commendation for the Judgment Ring system. For years, developers have been trying to answer the question -- how do we make battle scenes more involving than just picking selections from menus? In Shadow Hearts, the Judgment Ring is a dial with portions of the circle marked in green.

When you begin an attack, the dial begins to move, and you need to hit the action button as it crosses over the green segments. If you miss, you lose an attack, requiring quick reactions to successfully strike your foe. This in itself isn't particular innovative -- Square's Super Mario RPG featured something vaguely similar, which has since been reused in the whole line of Mario-inspired RPGs.

But these implementations are fairly shallow compared to Shadow Hearts, which features an extra element of risk. There are extremely narrow red slivers on the Judgment Ring, just on the edges of the green areas. If your timing -- and luck -- is good, then you can stop the dial on these segments to get some extra damage.

This idea is greatly expanded upon in Shadow Hearts: Covenant, as you can customize the size and type of Judgment Rings, allowing you to balance how greatly you want to play the game of risks versus rewards. As such, the fights are like slot machines that you can control. You can also turn them off completely, if you prefer the traditional way of fighting. But once you get used to it, you realize that major battles become all the more compelling when they rely on your reflexes -- and your willingness to take risks -- as much as your strategy.

Persona 3

Developer: Atlus

Publisher: Atlus (2007, PS2)

Potentially, Persona 3 could have been a trainwreck. A spinoff of the Shin Megami Tensei series, it features randomly generated stages, with a huge focus on dungeon crawling. One only need to look at the Western reviews (and sales) of such conceptually similar titles like Azure Dreams (PSOne), or The Nightmare of Druaga (PS2) to see that western JRPG fans traditionally haven't cared for these types of games.

Furthermore, it takes place in a high school, allowing the main character to interact with their classmates, join clubs, and socialize -- all elements of dating/life sims that are popular in Japan, but barely heard of in the west.

Of course, from Japan's point of view, it wasn't the first time that someone tried to combine life-sim elements with an RPG -- Sega's immensely popular (again, in Japan) Sakura Taisen series popularized the mechanics through its many installments. One of the only similar games released in America was Atlus' PSOne RPG Thousand Arms, which tried the same thing on a more limited scale, with disappointing results.

Taken separately, neither aspect of Persona 3 would've stood on its own. The dungeon crawling is repetitive, and while the battle system draws heavily on the same strategically brilliant system found in most the other PS2 Shin Megami Tensei titles (Nocturne, Digital Devil Saga), the player can only control a single character, drastically limiting the strategy that traditionally made the series so appealing.

The life sim part, too, is scaled down -- this style of gameplay pretty much began with Konami's Tokimeki Memorial, which offered over a dozen statistics to monitor in order to shape your avatar's personality, while Persona 3 only offers three. Yet, both portions come together so brilliantly that add up to more than the sum of their parts. There are plenty of clubs to join, and numerous NPCs to befriend or even date.

Socializing will enhance the strength of your Personas, the mythical creatures that dwell in your mind and provide your special attacks. The life sim segment of the game is essentially a character creation system -- usually, these are reduced to impersonal menus, but these have been removed in favor of something more involving, and ultimately, more rewarding.

Socializing will enhance the strength of your Personas, the mythical creatures that dwell in your mind and provide your special attacks. The life sim segment of the game is essentially a character creation system -- usually, these are reduced to impersonal menus, but these have been removed in favor of something more involving, and ultimately, more rewarding.

The extremely innovative scenario also goes a long way towards giving Persona 3 its charm. As a transfer student in a new school, you and some of your fellow classmates have the ability to sense the "Dark Hour", a mysterious period of time that occurs at midnight, where the rest of the world lies asleep and unaware. During this time, a huge tower called Tartarus warps and mangles the interior of your school, which is somehow tied in with a mysterious apocalyptic prophecy.

A lot of the enjoyment comes from trying to balance your school/social life with your demon hunting life, not exactly a typical dilemma faced in most RPGs. It also provides an interesting glimpse into the fantasy life of a modern Japanese teenager, as the game is filled with stylish artwork and a J-hiphop soundtrack that's alternatively catchy and grating.

Persona 3's big pseudo-controversy stems from the method where the characters summon their Persona -- they bring a gun to their head and pull the trigger, forcing their spirit companion out to attack. It's cool, in a punk kind of way, but the relative obscurity of the title allowed it to fly under the radar of the self-appointed culture warriors. This off-the-wall originality helped it earn rare accolades from the western press.

Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne

Developer: Atlus

Publisher: Atlus (2004, PS2)

The Megami Tensei series has come a long way since its inception back in the 8-bit Famicom days. Based on a campy horror novel from the '80s, Megami Tensei put you in the role of a young programmer who had used his computer to summon demons into the real world.

It was a first person dungeon crawler, keeping closer to games like Wizardry than Dragon Quest, but it featured an innovative mechanic where you could convince any enemy to join your party by chatting with them. The second game deviated from the novel and allowed gamers to explore a post-apocalyptic Tokyo. This concept was revisited in its two Super Famicom sequels, this time dubbed Shin Megami Tensei.

Much like Capcom and Street Fighter, Atlus had a hard time counting to three for Shin Megami Tensei sequels. Although it had strong cult popularity, it never got nearly the same exposure as Square or Enix's big guns, so Atlus attempted to bring in other audiences with a series of spin-offs, including the Persona and DemiKids series.

It wasn't until 2003 that they finally released a true third game, known in Japan as Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne. It was also the first true entry in the series released in America, so it dropped the Roman numeral.

Much like its earlier Famicom and Super Famicom brethren, Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne begins with the end of the world -- and with it, a new beginning. Whereas the previous game put you in the role of one of the last humans alive, trying to eke out an existence in a world full of angels and demons, Nocturne transforms your character into a demon.

The biggest difference from the previous Shin Megami Tensei games is the change from a first person viewpoint to third person, to appeal to an audience more familiar with Final Fantasy, no doubt. The addition of impressive, creative 3D demon designs also added a lot of appeal.

The biggest difference from the previous Shin Megami Tensei games is the change from a first person viewpoint to third person, to appeal to an audience more familiar with Final Fantasy, no doubt. The addition of impressive, creative 3D demon designs also added a lot of appeal.

Make no mistake though -- these changes were not meant to castrate the series for the sake for higher sales. Nocturne is still quite difficult -- almost maddeningly so. Like most of the best RPGs, grinding through the quest will get you absolutely nowhere. Your goal is to recruit as many monsters as possible, but even that won't do any good if you don't know how to use them.

In most modern RPGs, paying attention to elemental affinities makes the game easier, but it's hardly required. In Nocturne, it's an absolute necessity. If you hit the enemy with an attack they're weak to, they'll lose a turn -- but, of course, the same is true for your team. In order to succeed, you need to become familiar with the attacks of each and every monster in the game, especially since most foes can just as easily become your friends.

Enjoying the game requires an intense amount of devotion, which can potentially be too exhausting for those who don't like to memorize demon fusion charts. But it's also extraordinarily rewarding, especially given the absolutely enthralling vision of post-apocalyptic Tokyo. The ruins of humanity are encased in a fuzzy red haze, the standard office buildings replaced by stylish fortresses crafted by Hell's finest architects.

The story mostly revolves around the few surviving humans -- some of whom were your friends in your previous life -- and how they've dealt with the end of the world, which in turn contrasts with your actions. Past the opening sections of the game, the narrative is a bit sparse, but the vision of the world and how it unfolds is reason enough to stick with it to the end, no matter how many times those monstrous Fiend bosses kick your tail.

Final Fantasy VIII

Developer: Square

Publisher: SquareSoft (1999, PS2)

Gamers are very familiar with Final Fantasy VIII's many quirks and failings. The game world is strangely inconsistent, trying to shovel modern elements into a world that otherwise feels too medieval. Everything from its story to its battle system is slow, bloated, and unnecessarily confusing. And yes, Squall is an unlikable jerk, and his romance with Rinoa is not quite believable, considering it's meant to be the crux of the game.

There's a lot that Final Fantasy VIII does wrong, but there's even more that it does right. There are so many JRPG conventions that Square deliciously twists that it's almost like relearning how to approach the genre. At the core of this is the Junction system, which allows you to use magic spells to increase your stats or modify your elemental abilities.

This completely shatters the concept of RPG equipment, which has only occasionally veered beyond the "go to new town, buy new stuff, sell old stuff" pattern. Since there is no armor in Final Fantasy VIII, the spells you draw from enemies let you make your own. Similarly, weapons are primarily upgraded in the same manner -- there's some new equipment that can be assembled if you run some enemy hunting quests, but they're presented as subquests rather than necessary requirements.

Magic use has also been completely reimagined. Since the original Final Fantasy, we've been taught to conserve magic as a precious resource, dwindling to the point where our MP would reach zero and we'd need to retreat to an inn to recharge.

Yet magic is everywhere in Final Fantasy VIII -- all you need to do it is draw from any enemy creature. Of course, the dynamics of this system completely depend on the enemies on the area -- if they possess Fire magic, you can go crazy setting enemies ablaze, but if none of them have healing magic, you'd better conserve your Cure spells.

Yet magic is everywhere in Final Fantasy VIII -- all you need to do it is draw from any enemy creature. Of course, the dynamics of this system completely depend on the enemies on the area -- if they possess Fire magic, you can go crazy setting enemies ablaze, but if none of them have healing magic, you'd better conserve your Cure spells.

Similarly, RPGs have always been trying to seek a balance between magic and power. Fighters have always been more powerful than magicians, a point made explicitly clear in Final Fantasy VII, where magic Materia would weaken your strength and HP stats.

Using magic in Final Fantasy VIII will weaken whatever statistics that spell is Junctioned too, again forcing you to be aware of how to formulate your strategy. It's the same concept as before, just done in a completely different manner. This is one area that Final Fantasy has always specialized in -- keeping mechanics familiar yet overturning them in new and crazy ways, just to keep you on your toes.

It can be a bit overwhelming, which is why a lot of gamers initially ignored the system in favor of spamming the summon beasts, each of which were accompanied by overly long, drawn out cinemas. As such, there's a strange divide – if you fully understand the ins and outs of the system, you can totally break the game; but if you don't, it becomes obnoxiously difficult.

Still, those who like to micromanage stats and completely beef up the characters -- potentially the same kind that would find Final Fantasy V to be paradise -- can feel right at home with Junctioning. So ignore the sloppy romance and the trashy love ballad that goes along with it -- this is what Final Fantasy VIII should be known for.

Earthbound

Developer: Nintendo

Publisher: Nintendo (1995, SNES)

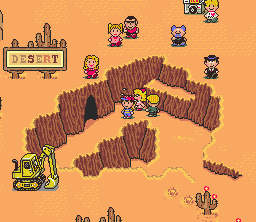

Few games have such a rabid cult fan base as Earthbound, known as Mother 2 in Japan. The first game in the series, released for the Famicom, almost left Japan, but never made it. Its sequel, this game, is regarded as one of the greatest RPGs on the SNES.

From a gameplay standpoint, there is very little new or interesting about Earthbound. It is an unabashed Dragon Quest clone, right down to the squat mini-characters and first person viewpoint on the battlefield.

The elimination of random battles is a nice touch, but other than the HP counter (which slowly drains when you take damage, potentially allowing for an extra hit before you fall), it could easily qualify as one of the many Dragon Quest ripoffs that flooded the Japanese market.

Yet Earthbound succeeds almost entirely because it's something so rare in gaming -- a parody. With all of its tragically melodramatic plot devices and absurd coming-of-age stories, the JRPG genre is ripe for hilarity, yet few games (outside of some fan-made games, like the near-brilliant Barkley Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden) ever seem to try it.

Earthbound begins with a young boy named Ness, whose journey is spelled out by a small alien the size of a house fly. Mistaking it for an insect, your neighbor's mom ends up swatting it, as the tragic music plays and the poor creature lays out the rest of your destiny in its dying breath.

From there, Ness adventures around the globe, gathering up party members and fighting against both nasty invaders from outer space and the equally kooky townspeople. The final stages culminate in a weirdly absurd plot twist, and yet it almost completely makes sense in the bizarre, backwards world of Earthbound.

Pretty much every aspect of the game is taken outside of the bounds of absurdity. Ness and his friends look like they were ripped out of a Peanuts cartoon, except they can wield psychic powers. One of the NPC sprites looks just like Mr. T. At one point, you run into a band that's a pretty obvious homage to The Blues Brothers.

Pretty much every aspect of the game is taken outside of the bounds of absurdity. Ness and his friends look like they were ripped out of a Peanuts cartoon, except they can wield psychic powers. One of the NPC sprites looks just like Mr. T. At one point, you run into a band that's a pretty obvious homage to The Blues Brothers.

Many of them have bizarre, frightening, permanent grins on their faces. The prologue seems ripped out of a 50s sci-fi TV serial. Some of the first enemies you fight are hippies, whose primary method of attack includes mocking you and calling you names.

The whole game is a warped, confused tribute to American culture, designed by people who've only experienced the country through books and movies. Yet it's never offensive or misguided -- rather it's a lovingly-crafted universe with a sly sense of humor that can't be found anywhere else.

Between all of the wackiness, there are some oddly poignant moments. As a young child wandering far away from home, you're constantly calling your father -- who only shows up as a voice over the phone -- in order to save your game and replenish your funds. It's strange that Earthbound can take something as impersonal as save points and turn them into one of the few reassuring voices in a world gone mad.

With its schizophrenic music, which bounces between "quaintly touching" and "hypnotically grating", and drugged-out psychedelic battle backgrounds, Earthbound occasionally feels a bit too weird-for-the-sake-of-weird. But let's face it -- with originality in short supply, it's hard to argue against that any of these are bad things.

Grandia

Developer: Game Arts

Publisher: SCEA (1999, PlayStation)

Game Arts' Lunar series has a pretty decent following, especially amongst English speakers. This was mostly because it was one of the few JRPGs of the 16-bit era that received competent translations thanks to Working Designs.

After the original two releases (for the Sega CD), their remakes (for the Saturn and PlayStation), and a completely negligible side story (Magical School for the Saturn and Game Gear), fans kept clamoring for a new Lunar installments.

What Lunar fans perhaps may not have realized is that the series' spirit lived in Grandia, another series by the same company. It may be missing the interesting mythology behind the Lunar world, and they definitely falter from the lack of Toshiyuki Kubooka's distinctive character artwork, but they practically perfect one area where JRPG developers often still can't get it right -- the battle system.

Considering you spend a huge portion of any JRPG in battle, it's a wonder that so many games are dull or plodding or just plain irritating. Grandia introduced a pseudo-real time battle system that not only forces strategy on to the player, but also manages to be enthralling, quite an achievement considering that you're still just picking selections from menus.

During battle, each character's turn order is depicted on a gauge at the bottom of the screen. The action unfolds in real time -- similar to Final Fantasy's Active Time Battle system -- except you're made explicitly aware of your foes' places in the turn queue, allowing you to plot accordingly. The action pauses whenever one of your character's turns comes up, allowing you to make a move.

In addition to the usual magic spells, each character has two primary attacks -- a "Combo", which consists of multiple powerful attacks, and a "Critical", a single, quick attack. There's a short delay between the time when an action is decided and when it's actually executed, indicated on the action gauge as a line of red. If you manage to hit an enemy with a Critical attack during this small window, you'll stun the enemy and cause them to lose their turn.

On the flip side, if you're not paying attention, the enemy can do the same thing to you. As a result, each time you pick a command, you have to weigh your decisions, be mindful of the speed and distance of your attacks, and take some risks at every turn. If you play it smart, it's possible to emerge from battle completely unscathed, which rewards you with additional experience and a special victory theme.

On the flip side, if you're not paying attention, the enemy can do the same thing to you. As a result, each time you pick a command, you have to weigh your decisions, be mindful of the speed and distance of your attacks, and take some risks at every turn. If you play it smart, it's possible to emerge from battle completely unscathed, which rewards you with additional experience and a special victory theme.

The shaky camera in the first game adds to the chaos, zooming around the battlefield and focusing on the most brutal attacks. Crushing sound effects accompany every blow, and slain enemies that explode in a mess of coins and shattered polygons. These effects were toned down once the series went 3D in Grandia II, which is a bit of a shame

The first Grandia is most like the original Lunar games, featuring the story of a young boy named Justin, adventuring out into the world and eventually taking down an evil empire. It's clichéd, but it's eminently likable and the strongest of the series.

The second features an interesting protagonist by the name of Ryudo, and while it starts off strong, it tragically devolves into a silly plot wherein you must destroy the world's pseudo-Pope. Grandia III, while gorgeous, collapses even further into banal storytelling, with only a few side characters holding up a plot that's weighed down by the moronic starring cast. Yet, again, it's the battle system that keeps all of the Grandia games afloat, and makes them all worth checking out.

Final Fantasy XII

Developer: Square Enix

Publisher: Square Enix (2006, PlayStation 2)

Final Fantasy XII does so much to reinvent the JRPG template that it hardly belongs in the same genre, much less part of the Final Fantasy series. Concepts like the "field map" and "battle scenes" have all been blended together into a more cohesive whole.

At the crux of this are the guild hunts -- featuring a huge slew of subquests that can keep obsessive gamers busy for scores of hours -- and the Gambit system, which administers the real-time fighting segments, which have graduated beyond the random battles of RPGs past.

The Gambit system essentially allows you to program all of your characters' AI rotuines, so you don't need to issue individual commands to your party. While many other action-oriented RPGs have similar features (like the Star Ocean and the Tales series), Final Fantasy XII offers a lot more freedom in customizing your actions.

The most basic Gambits can simply tell all of your characters to attack the same monster as the party leader, or simply target the enemy with the lowest HP. If one of your allies HP dips below a certain percentage, it will trigger one of your members to cast a healing spell. And so forth.

The idea is that you're creating a machine which constantly needs tweaking and adjusting, until you've found a combination of commands that works for the party you've built and the enemies you're facing. And, really, this is what all combat is in any JRPG anyway -- looking for the most efficient ways to kill bad guys while managing your resources, all without the crazy flashing screen changes that have marked every JRPG since their inception.

It's not just the Gambit system that sets Final Fantasy XII apart. It also has a story and game world so vastly different from its brethren. It's undoubtedly the classiest and most mature entry in the series, and the only game it remotely channels is the spinoff Final Fantasy Tactics.

Both of these games were helmed by brilliant game designer Yasumi Matsuo, who rather infamously quit the FFXII team during development. Matsuno seems to have had an admiration of tales of tragic war and Shakespearean drama, all triumphantly backed by the music of Hitoshi Sakimoto, whose orchestrations feel more significant than Uematsu's synth-heavy new age/prog rock found in the prior Final Fantasy games.

However, there's a bit of duality as a result of Matsuno working on a more "popular" title -- his games always felt a little bit more legitimate since he never appeared to be selling out, but Final Fantasy is a series that creates characters designed to appeal to its ardent fanbase.

Not to say some of his games have been completely devoid of more lurid fan-baiting qualities -- did anyone in Vagrant Story actually wear pants? -- but when you're used to his kind of authenticity, it's a bit disconcerting to find yourself wondering how long it takes Vaan to get his hair so perfect, or wondering how anyone can take a princess seriously when wearing the kind of hot pants that Ashe tries to pull off.

Not to say some of his games have been completely devoid of more lurid fan-baiting qualities -- did anyone in Vagrant Story actually wear pants? -- but when you're used to his kind of authenticity, it's a bit disconcerting to find yourself wondering how long it takes Vaan to get his hair so perfect, or wondering how anyone can take a princess seriously when wearing the kind of hot pants that Ashe tries to pull off.

In FF Tactics Advance, the Viera were cutesy in the same way that Beatrix Potter's Peter the Rabbit would be cutesy, if he were wielding a bow and arrow. Here, the dark skinned, light haired Fran wears a metallic thong, and the camera takes great delight in panning up her backside. As such, it's the highlights -- if not necessarily the best parts -- of both worlds.

The Final Fantasy series has always divided fans in a way no other series has, but Final Fantasy XII is bound to infuriate more than most -- and, as one can be probably guess, most of it was probably Matsuno's fault. It's so drastically different from not only its predecessors, but practically any modern role playing game out there, and its expansiveness attract as many as it offends. The plot and characterizations start off strong, but soon dwindle and lose focus amongst the numerous dungeon crawls at the game's end.

Plot threads get resolved as soon as they begin, if they go anywhere at all. And yet, the de-emphasis on storytelling is a fine alternative to the plot heavy Final Fantasy X, or even to any of the cinematically linear PSOne titles.

As one of the biggest concessions between old school and new school, when you defeat a major boss, your characters will all stand around in circle and do a winning pose to the tune of the classic victory theme. This throwback serves as a reminder to how silly all of the past RPG conventions have been, at the same time perhaps making the player realize that they don't miss them.

Dragon Quest V

Developer: Armor Project/Chunsoft/Enix

Publisher: Enix (1992, SNES)

As of this writing, there are eight installments in Enix's Dragon Quest series, all of which are notable to some extent. While most longtime Final Fantasy fans can probably agree that FFVI (or FFVII, depending on who you talk to) was the standout of the series, the line grows much blurrier with the Dragon Quest games.

This may seem a bit strange to those outside the DQ fan circle. The series has prided itself on its consistency in every aspect from its game world to its character designs to its soundtrack to its battle system, yet each of them remains distinctive to those that know and love them.

Dragon Quest III is heralded by Japanese gamers as one of the best titles on the Famicom for its then-epic plot and customizable characters, while others prefer Dragon Quest IV for its chapter-based storytelling and memorable cast of characters.

Most English fans may more fondly remember 2005's Dragon Quest VIII, which finally gave into modern influence by featuring luscious cel-shaded graphics, a cinematic battle system, and, for the American release, splendidly charming voice acting.

Yet amongst the entire series, one of the most significant is the Japan-only Dragon Quest V. Coming of age is a common theme in JRPGs, yet never has it been executed so magnificently as Dragon Quest V. Your hero starts as a young child, barely unable to fight a pack of slimes on his own without his father's help, and goes on crazy adventures before even learning to read.

By the end of the game, he's lived through a slave labor camp, explored the world, fallen in love, raised a family, and entered into another evil dimension, for the sake of not only saving the world, but growing up. Effectively, it's the RPG equivalent of an epic, detailing the story the story of three generations of heroes. Sega's Phantasy Star III for the Genesis tried something similar around the same time, but Dragon Quest V is a much more personal story, and also happens to be a far stronger game overall.

By the end of the game, he's lived through a slave labor camp, explored the world, fallen in love, raised a family, and entered into another evil dimension, for the sake of not only saving the world, but growing up. Effectively, it's the RPG equivalent of an epic, detailing the story the story of three generations of heroes. Sega's Phantasy Star III for the Genesis tried something similar around the same time, but Dragon Quest V is a much more personal story, and also happens to be a far stronger game overall.

Although the game ditches the class system introduced in DQIII (later reused for both DQVI and DQVII), it allows you to build a party consisting of defeated monsters. Although it's a bit haphazard trying to draft foes on to your team, it's a lot more customizable than most RPGs when you have dozens of playable party members at your disposal.

It's essentially the same mechanic used in the Megami Tensei series, although it doesn't require that you memorize huge charts of enemy abilities to succeed.

Far too many games (including Dragon Quest's own spinoff, the Monsters line, as well as Nintendo's Pokémon series) focus on the monster collection as the primary game mechanic. On the other hand, all subsequent Dragon Quest games have utilized some similar method of drafting enemy monsters, but they're largely afterthoughts to other character customization systems.

In Dragon Quest V, it's so seamlessly integrated into the main system, without becoming overwhelming, that it's a textbook example of how to do the monster collection thing right.

Panzer Dragoon Saga

Developer: Team Andromeda

Publisher: Sega (1998, Saturn)

Modern gamers -- those brought up on fancy, high tech polygonal magic -- scoff at Final Fantasy VII's texture-less character models and low-res prerendered backgrounds, claiming that these are grounds for a remake. Yet the ravages of age have been harsher on Sega's Panzer Dragoon series.

While the first two titles were simple arcade-style shooters, they amazed gamers of the mid-90s with a gorgeous game world, drawing equally from the likes of Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaa and the works of French artist Moebius.

It's a strange mixture of fantastic organic creations and high tech wizardry, the likes of which haven't been duplicated in any other medium. Unfortunately, the Saturn was hardly a 3D powerhouse, and what used to be daring and gorgeous is now pixellated, choppy, and in some areas, downright offensive.

The same visual issues plague the third Panzer Dragoon title, Panzer Dragoon Saga. In some ways, they're even worse -- the first two titles were shooters which took place on the back of a dragon, flying high above the smeary textures and low polygon landscapes. Saga is an RPG, where you'll spend a much time walking around on foot -- where the technical issues are even more apparent.

And yet, once you get into it, none of this really matters. In the old titles, the story was simply told through CG cutscenes, and the world existed only as a background to fly over. When you're interacting with the environments, walking through them or talking to their inhabitants, it shows how much effort was put into creating a completely unique setting and culture.

Panzer Dragoon Saga feels like you're walking through a museum detailing a lost culture that never was, from a forgotten period of humanity's history that has never existed. The only concession is that the world's unique, made-up language (dubbed "Panzerese" by fans) was ditched in favor of Japanese. But since the game was localized without English dubbing, relying instead on subtitles, it still feels foreign to Western gamers, even if it's not in the same manner.

Panzer Dragoon Saga feels like you're walking through a museum detailing a lost culture that never was, from a forgotten period of humanity's history that has never existed. The only concession is that the world's unique, made-up language (dubbed "Panzerese" by fans) was ditched in favor of Japanese. But since the game was localized without English dubbing, relying instead on subtitles, it still feels foreign to Western gamers, even if it's not in the same manner.

The battle system also takes a radical departure from the norm. All battles are fought in mid-air, as you're flying on your dragon. The action takes place in real time, with three power bars that charge over the period of a few seconds. At any point, you can pause the battle and choose to attack -- if you've built enough power, you can attack multiple times, or unleash a single, more powerful attack.

Positioning is also extremely important -- your dragon flies in one of four quadrants surrounding your enemies, and can move between them at will. Your radar, at the bottom of the screen, will mark which zones are safe and which are dangerous. If you're flying in a green zone, the enemy can't attack; if you're in a neutral zone, the enemy can use a weak attack; and naturally, the red zone indicates that the enemy can use a fierce attack.

Obviously, you'll want to spend as much time as possible charging in the green zones to avoid damage. However, enemies often have weak points in other positions, encouraging you to fly in the face of danger to finish battles efficiently.

The enemy's attack patterns often change multiple times during battle, forcing you to adapt and figure out the optimal positioning, timing, and type of attacks to use. Furthermore, you have precise control over the development of your dragon, determining how fast it is, how powerful its attacks are, and other statistics.

Panzer Dragoon Saga is, however, remarkably short. Despite utilizing four discs -- mostly for pixellated, heavily compressed video, which looked frighteningly bad compared to Square's efforts -- the quest clocks in at roughly fifteen hours. Considering that the English game often fetches triple digit prices in the aftermarket, it's somewhat of a rough investment. But it's a totally unique game, with a world and combat system completely unlike anything else.

Final Fantasy X

Developer: Square

Publisher: SquareSoft (2001, PlayStation 2)

Ever since the early days of interactive fiction, game developers have been wondering -- how does one tell a story using video games as a medium? The advent of the laserdisc -- and later, the CD-ROM -- gave developers the wrong idea, by churning out full motion video titles that, while cinematic, had limited user inputs.

For a long time, Western developers favored the graphic adventure as a means of storytelling, while the Japanese preferred role playing games, which replaced the mind-bending puzzles with battles and character building. At the forefront of this movement has been Final Fantasy, which has been consistently impressive, partially because of the huge budget and manpower put behind them.

At the pinnacle of JRPG storytelling is Final Fantasy X. It was voted in 2006 as the best video game of all time by the readers of Famitsu, the premiere Japanese video game magazine. At the core of the story is Tidus, a young athlete whisked away to another world. This land, dubbed Spira, is a gorgeous tropical paradise, yet is under the constant threat of a giant monster named Sin.

Tidus eventually join a pilgrimage to stop it, joining along with a young summoner named Yuna. Final Fantasy VIII told its love story two years before FFX, but hiccups in execution -- including a divisive main character -- allowed room for improvement. Tidus is much brighter and friendlier, even if he is a bit whiny. He joins the pilgrimage mostly because Yuna has something of a crush on him.

It actually tells a compelling story this time around, and the romantic climax -- featured on the cover of the American manual -- is far more involving than the similar scene in FFVIII.

Spira is one of the most gorgeously realized worlds yet rendered into a video game. While Square's mediocre beat-em-up The Bouncer was meant to show off what kind of graphical tricks the PS2 could pull off, Final Fantasy X was Square's first real RPG on the system, and they didn't spare any expense.

The world is loosely inspired by the Okinawa region, which is why this game feels more Japanese than any of its culturally neutral predecessors. One of the reasons Final Fantasy stands out from its peers is the way its game worlds refuse to be pigeonholed into genre classifications -- none can be defined strictly as "medieval" or "sci-fi". Although some inhabit the nebulous zone in between those descriptions, Spira defies pretty much everything and is by far the most unique of all.

The world is loosely inspired by the Okinawa region, which is why this game feels more Japanese than any of its culturally neutral predecessors. One of the reasons Final Fantasy stands out from its peers is the way its game worlds refuse to be pigeonholed into genre classifications -- none can be defined strictly as "medieval" or "sci-fi". Although some inhabit the nebulous zone in between those descriptions, Spira defies pretty much everything and is by far the most unique of all.

It's a strange world, filled with its own culture, religion, and even metaphysics, and the whole game is about how these clash with not only Tidus' feelings, but the player's as well. At the very least, Final Fantasy X's world gives some context to Tetsuya Nomura's occasionally outlandish character designs, even if some, like the goth girl Lulu, still seem to exist more as a fetish object than a true inhabitant of the land.

Most of this involvement comes from the narrative, which is far more involving than any game before -- or, arguably -- after it. Before Final Fantasy X, major plot points were handled by squat little sprites or awkwardly constructed polygonal models, both with very limited ranges of emotion.

Almost everything here is represented with a fully animated, fully voiced cutscene. Even the dialogue boxes of the non-voiced sections are gone, replaced with subtitles. Whereas many of the previous Final Fantasy games were games with story elements, this is a story with gaming elements

However, sometimes the narrative pushes just a little too hard. It's hard to say there are any real dungeons in Final Fantasy X -- most of the adventuring requires walking in a straight line, with an occasional branch that leads to treasure. It takes a few hours before the game loosens its reins and stops giving tutorials. This ensures a well-paced story, but it also drastically limits the sense of freedom, an element which is already pretty rare in most JRPGs.

There are also tons upon tons of cutscenes, all of which are unskippable. It also highlights another problem -- if the player doesn't like the story, there's very little of worth here. The battle system, which ditches the Active Time Battle system of the previous Final Fantasy games, is fast and fun, but the character development system -- the Sphere Grid -- is pretty lacking. Even if you didn't care of Squall or Rinoa's antics in FFVIII, at least you had the Junction system to play around with.

In Final Fantasy X, the most interesting parts of the Sphere Grid don't open up until the later portions of the game, far too late for those who aren't immediately drawn in by the tensions between Tidus and Yuna. It doesn't help that, like many of the Final Fantasy games, it tends to devolve into ludicrousness -- the monster that terrorizes Spira is actually Tidus' drunken father, the kind of wholly absurd metaphor for filial tension that would potentially get one laughed out of their high school creative writing class.

But again, like most JRPGs, once you accept it on its own terms -- silly melodrama and all -- it remains a completely original, fascinating, even emotional tale. As a piece of video game storytelling, Final Fantasy X doesn't quite reaches the heights of, say, Metal Gear Solid 2 or BioShock, both of which use the medium in ways that other kinds of fiction can't.

But as a cinematic experience, featuring interesting characters and a beautifully realized alternate world, it walks an agreeable line between narrative and gameplay, even if it tends to err too far from the gameplay side.

Skies of Arcadia

Developer: Overworks

Publisher: Sega (2000, Dreamcast)

In Sega's Skies of Arcadia, you're the leader of a group of air pirates -- made explicitly clear to be "good guy pirates" -- traveling the world over, fighting all kinds of "bad guy pirates", and helping anyone in need. The world is largely unknown, comprised of dozens of islands floating in the skies, miles above the poison that lies on the surface of the earth.

The explorer's map that shows your ship's position slowly expands from a tiny circle to a gigantic view of the entire world, keeping note of the myriad artifacts you discover. The hero Vyse is surrounded by two lovely ladies -- his fiery childhood friend Aika and the mysterious demure newcomer Fina. By the end, everyone flies into the metaphorical sunset, dreaming of all of the adventures yet to come. It feels like the end of the best Saturday morning cartoons never made.

Around the same time, the holiday season of 2000, Square released Final Fantasy IX. If Final Fantasy VII's theme was "life" and Final Fantasy VIII's was "love", then Final Fantasy IX was "history". It was meant be a concession to old school fans of the series, one that would adapt some of the themes of the older games and put them into modern trappings.

It was well intentioned, and a very solid title -- black mage Vivi remains one of the most noteworthy characters in the Final Fantasy canon -- but all that resulted was a fairly simplistic game with all of the bloat of the other PSOne Final Fantasy titles, without the impressive storytelling -- in short, it tried to be the best of both worlds without reaching either. What Square didn't realize is that you can't elicit nostalgia just by simplifying the customization systems or name checking events from older games.

And this is the reason why Sega's Skies of Arcadia manages to touch so many gamers' hearts -- quite simply, it feels like childhood. As if springing from the imagination of a five year old, it elicits a feeling of wonder and imagination -- that behind everything lies something daring and new.

It harkens back to the time when your backyard was full of dangerous creatures, and the local swamp was inhabited by dinosaurs, and the sewers were an intricate series of mazes that ended up treasure. It's the exact same sentiment of the Legend of Zelda series, before it fell prey to the crushing throes of tradition. And it never feels like its pandering like Mistwalker's Blue Dragon, which just seemed to be trying too hard. It's a breezy, natural, and altogether remarkable game.

It harkens back to the time when your backyard was full of dangerous creatures, and the local swamp was inhabited by dinosaurs, and the sewers were an intricate series of mazes that ended up treasure. It's the exact same sentiment of the Legend of Zelda series, before it fell prey to the crushing throes of tradition. And it never feels like its pandering like Mistwalker's Blue Dragon, which just seemed to be trying too hard. It's a breezy, natural, and altogether remarkable game.

Of course, none of this would've worked if there wasn't anything interesting beneath the shadows of the world map, but Skies of Arcadia succeeds because there is no generic dungeon, no faceless town. Everything from the secretive underground pirate's base, to the tree clubhouse feeling of the jungle city of Hortec, to the gorgeous waterfalls and Asian-inspired shrines in Yafutoma, to the Middle Eastern desert lands of Nasrad.

You don't even need to talk to the inhabitants to understand the culture behind the game's nations -- all you need to do is walk through their country. Dungeons don't just seem like some landscape you're walking over -- each and all of them have depth and texture, the kind that you'd usually see in platform or action games. In fact, this devotion to architecture is what gives Skies of Arcadia its unique identity.

The rest of the game is not exactly perfect, and does fall victim to some dull game design. The combat system is a bit plodding, with its gimmick lying in a super energy bar shared amongst party members, allowing for special attacks. The constant random battles, especially in the original Dreamcast release, don't do it any favors either. Ultimately, though, Skies of Arcadia has all of the straightforward charm of a 16-bit games wrapped up in modern trappings, an unfortunate rarity in the field.

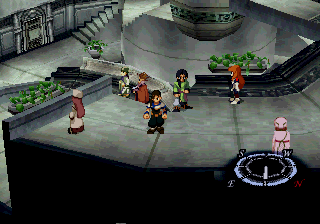

Chrono Cross

Developer: Square

Publisher: SquareSoft (2000, PlayStation)

Chrono Cross is only barely the sequel to Chrono Trigger. Trigger's call to fame was its assemblage of Square and Enix, Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, Sakaguchi and Horii. With the Enix folk unavailable to participate in a follow-up, it left Square with their own devices to take up the task.

Even then, the key players had either moved on or evolved -- writer Masato Kato had since been in charge of penning Xenogears and his scripting tended to waft into metaphysical territories; musician Yasunori Mitsuda had been bitten with the Celtic bug, giving his music a distinct sound that, while becoming exemplary in the field of video game music, lacked the variety that kept Trigger so much of its energy; and Hironobu Sakaguchi was too busy sinking Square from the inside with his work on the Final Fantasy: Spirits Within movie.

Akira Toriyama's distinctive designs are out -- his spot is taken by Noboteru Yuuki, who tries to maintain the same goofiness of Trigger's designs but ends up overcompensating by drawing some of the most bizarre cast members seen in an RPG, including a talking radish and a video game rendition of Aunt Jemima.

So Chrono Cross barely looks, nor sounds, nor plays like its predecessor, and yet it's one of the most sterling examples of an RPG sequel. Final Fantasy, outside of FFX-2, as well as most JRPGs, rarely have any real plot continuity, while a few others like Phantasy Star and Dragon Quest tie its stories together loosely into overarching legends or events.

Cross does not intend to retell the adventures of Crono, Lucca or Marle -- their adventures, as far as the players were concerned, had finished. Rather, Cross expands significantly on both the mythos of the series and concept of time travel. For better or worse, it's The Odyssey to Trigger's The Ilyiad, in the way that it takes a relatively minor aspect of its predecessor and makes it the focus.

The time travel in Trigger was very light-hearted and straightforward -- if something was wrong in the present, you simply went back in the past and corrected it. Cross asks the question -- what happens to that original timeline, before it's corrected? It doesn't simply disappear -- rather, a parallel universe is formed, and this is where we find the hero, a young fisher boy Serge.

The time travel in Trigger was very light-hearted and straightforward -- if something was wrong in the present, you simply went back in the past and corrected it. Cross asks the question -- what happens to that original timeline, before it's corrected? It doesn't simply disappear -- rather, a parallel universe is formed, and this is where we find the hero, a young fisher boy Serge.

Serge ends up getting sucked into an alternate world. It's the largely the same as his own, with one huge difference -- he learns that his otherworld self drowned when he was young. Although seemingly insignificant, and unknown at first, this event has completely reshaped the history and events of the otherworld.

Even though Trigger was a largely gloomy game, what with the incoming threat of the apocalypse looming over the heroes for a majority of the game, Cross is even more somber. Part of this is because Lavos, the big bad guy from Trigger, isn't actually dead. We learn that it exists somewhere outside of time, virtually invincible.