Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Who should be able to experience art? While in an ideal world the answer is everybody, there are various groups of players that are unable to engage with video games for numerous reasons. For some that reason may be difficulty, so let's talk about Sekiro.

Who should be able to experience art? The gut answer – the ideal answer – is everybody. No one should be prevented from experiencing art. Yet every form of art has a portion of its audience that is prohibited from it in some way. In many cases, we have adapted accessibility countermeasures to try and minimize that prohibited group, but even in the cases where they work, they can fundamentally change the core experience. More to the point, video games have an additional unique barrier to entry and enjoyment; difficulty.

Every game has a difficulty. Anything within such an interactive medium is going to inherently possess some level of challenge or strain. This difficulty can come in the form of a puzzle, a level, a boss, or even the core controls within a game. Each of these different aspects of a game might have varying degrees of difficulty alone or in conjunction with one another throughout the experience.

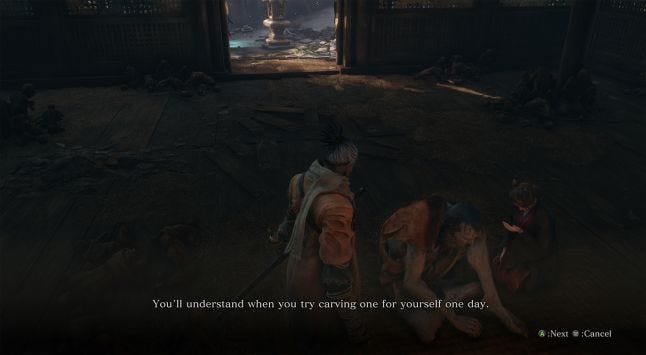

That fluctuation and variation is a major part of why difficulty is such a (pardon the pun) difficult topic to discuss; it’s subjective. A boss in Dark Souls 3 (From Software/Bandai Namco, 2016) or even an entirely new game and system like Sekiro (From Software/Activision, 2019) will likely be very different for a player with multiple hundreds of hours with games by the same studio, then it would be for someone jumping into the library for the first time.

Conversely, someone with any number of hours in Stephen’s Sausage Roll (Increpare, 2016) will undoubtably be more adept at the puzzles within and have a greater comprehension of the mechanical systems than me.

Truth be told, even writing this is opening up a potential rabbit hole with every other sentence. The difficulty of a puzzle game with only one set solution requires a different conversation than a traditional coin-op game with only one set difficulty. Both are different than the classic difficulty system of Easy/Medium/Hard difficulty selection. Then there are games with adaptive difficulty that tweak the challenge on the fly, and procedurally generated games where the difficulty is partially random based on context and circumstances.

All of those different game genres, systems, and mechanics are lying under the hood of any discussion about difficulty. But if talking about one then demands talking about them all, it becomes impossible to have meaningful discourse about the problem of prohibitive art due to game difficulty.

So, I guess what makes the most sense is to divide this into parts. (I sure hope this doesn’t get out of hand.) Discussions of difficulty can often devolve into multiple parties using the same words with incongruous definitions and ideas behind what they say. So, first I want to really break down what difficulty and challenge can mean – explain the nuance under the hood and see how it can differ between experiences. From there, I’ll go more into the “why” behind difficulty, talking about what it can mean to players and to games. Then finally, we’ll arrive at the crux of the discussion; accessibility, acceptability, and accountability.

Part I: What is Difficulty?

In short: A subjective mess.

In long:

Difficulty, as a word, can mean the state or condition of being difficult; or a thing that is hard to accomplish, deal with, or understand. That second definition is going to be a lot more applicable within the context of games.

Games can generally be understood – at least for this conversation – as an interactive experience that poses a challenge for the player to overcome. This can take the form of a level in Steven’s Sausage Roll (Increpare, 2016) or other puzzle games, a floor in Binding of Isaac (Edmund McMillen/Florian Himsl, 2011) or other roguelike games, a mission or quest in Borderlands (Gearbox Software/2K Games, 2009), or a match in competitive games like League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009) to name a few examples.

This challenge has two states, success/progress/achievement or failure/punishment/loss. But if every game was only ever filled with the success/progress/achievement state then not only would there be no need for this to all be written out, there would be no difficulty – or arguably even games – at all.

A game is created by the inclusion of a possible loss-state into a task.

Jesper Juul, game designer, educator, and theorist wrote, “Failure can be described as being unsuccessful at some task in a game, and punishment is what happens to the player as a result.”

He explains four types of punishment:

1) “Energy punishment: The loss of energy, bringing the player closer to life punishment.

2) Life punishment: Loss of a life (or “retry”), bringing the player closer to game termination.

3) Game termination punishment: Game over (often coupled with setback punishment).

4) Setback punishment: Having to replay part of the game; losing abilities (Juul, 2009).

This can be applied on every level of gameplay. Missing a shot leads to losing ammunition, mistiming a jump leads to taking damage, repeated mistakes or a big enough single mistake leads to death, too many deaths leads to a game-over or putting the game down. With countless minor instances along the way.

But when most of us say that a game is difficult, we’re not taking the time to pinpoint what type of loss or punishment we are undergoing – we just experience the path of: Hey this is pretty difficult. Wow, this is really difficult. OH MY GOD, THIS IS GAME DUMB.

Difficulty, as a more layman idea, is the challenge posed by gameplay. Harder, more complex challenges are more difficult, while easier and/or simpler challenges are less difficult. If the challenge is killing an enemy, then that enemy having more health, damage, armor, turns, resources, etc. is empirically more difficult. It would take more effort/resources from the player to overcome that obstacle.

But that’s kind of where the objectivity and empirical talks ends – when in relation to itself. An enemy B can only be truly be more difficult than another enemy A if it is the same type of enemy but with higher numbers. It is an upwards change in scale, and as such B will be more difficult than A. A downwards change in scale would mean they are easier, less difficult. However, if you have two different types of enemies then everything immediately goes to the wind.

So many different aspects of a game’s difficulty are also far more fluid than just numerical values. Things like the level’s design, the context of the player and the context of the enemy all factor in to how one interprets the challenge. Considering this, stating A is more difficult than B essentially becomes a vacuous statement that is mostly predicated entirely on that player’s subjective experience.

Just to elaborate really quick, the level design might mean changes in environment, layout, win/loss conditions, etc. Context of the player can mean anything from previous player experience with this or other games as well as how strong/weak the player-controlled character is. Context of the enemy means how they interact with the player, environment, or other objects/enemies around them. In short, two wolves together in a forest fight differently than a wolf alone in an empty room.

As an example, in Doom (id Software, 1993) facing off against 5 Cacodemons in a large open room with nothing but a shotgun is a very different experience than facing off against 5 Cacodemons in a narrow hallway with only a plasma gun. Both are fundamentally the same number and type of enemies with only one weapon at your disposal, but which one is harder sort of hinges on the player response and how those Cacodemons behave. Like with so many other parts of life, context is everything.

Needless to say, this makes talking about difficulty in video games for anything more in depth than, “hey, I thought this thing was hard…” “Hey, I also thought this thing was hard.” An extremely difficult (pun intended) conversation to have. To illustrate this, imagine a conversation between two players.

One, a fresh-faced real time strategy and city management game fan says, “Hey, is Sekiro difficult?”

The other person, a Soulsborne* series and From Software veteran says, “Yes, Sekiro is difficult.”

This exchange can mean something entirely different if you just swap who is saying which line… preferences, experience, mechanical skill, reaction time, and so much more all play an important part in how we each assess and communicate the difficulty of a game with ourselves and each other.

*(the collection of From Software’s game catalog spanning from 2009 to 2016 and beyond Including Demon’s Souls (From Software/Bandai Namco, 2009))

Part II: Variable Difficulty

Many games that we know and love have variable difficulties. Easy Mode, Hard Mode, Medium, Proud, Critical, Extreme, Epic, Nightmare, FUBAR, Apocalyptic, Silver, Gold, Normal, Story, Narrative, Heroic, Legendary, and on and on, you get the idea. These different modes serve to make each individual enemy or encounter easier or harder – which is logically followed by the game itself being easier or harder. Oftentimes these changes are merely an alteration of the numbers, in line with the more objective difficulty scaling previously mentioned. However, some games (particularly strategy games) typically do more to hamstring or bolster the opponent’s AI or behavior, which gets more into subjective difficulty. This variance can change from game to game and genre to genre – FPS difficulty is a different beast than Turn Based Strategy difficulty.

That said, puzzle games are typically exempt from this, as there are some games where the difficulty lies in determining an answer to a problem, not engaging in a form of combat or an active/reactive foe. But puzzle games could have variable difficulty! And some do; allowing for hints, showing additional clues, or even minimizing certain aspects of a puzzle in order for it to be ‘easier.’

Generally speaking, this process is done in order to allow more people to play the game. Accessibility for a wider audience to participate in the gameplay experience, which is awesome. But even here there is some variation. Some games have a set difficulty, and only get harder by introducing things like a New Game plus or unlocking additional harder difficulties. This can provide further challenge and engagement for those who like the game and its systems and are looking for a greater challenge.

Typically, these sorts of games will start out relatively easy and escalate quickly. Borderlands 2 (Gearbox Software/2K 2012) is a great example of this, with a pretty straightforward base game, much harder New Game Plus, and then a significant jump upwards for NG+2, the Ultimate Vault Hunter mode. This is, for some, where the real challenge of the game truly begins. For others though, this may be content that is too restrictive, preventing players without enough technical ability from progressing. But even those players have still been able to engage with a nearly all of the game’s full content.

Some games will offer up minor ways of making the game ‘easier’ while staying consistent. Heroes of Hammerwatch (CrackShell/Surefire.Games 2018) allows for particular buffs and various levels of pre-gameplay prep to give the players as strong of a chance as possible to ensure success. Even as the game gets progressively more challenging both throughout the floors and between New Game+ iterations, there are always slight optional tweaks that can be made to add or reduce strain for the players.

Some games, like Dark Souls (From Software/Activision, 2011), have various mechanics in the game that allow for a less dangerous way to play. Generally speaking, using sorceries and magic in the Dark Souls series can be considered an easier way to play, you don’t need to get within striking distance of enemies as often and can have less precise timing for attacking and evading. Certain enemies can even be poked and killed from so far away that they don’t even notice that they’re dying.

But then there are those games. Games where, like Dark Souls, there may be slightly ‘easier’ or less intensive ways to play as previously mentioned, but the game’s design and mechanics promote and push towards pretty universal standards of play. All this so far has been a lead up to the popular question that comes around every other year or so. It happened once with Cuphead (Studio MDHR/Marija and Ryan Moldenhauer, 2017), and now the conversation has buzzed up again with Sekiro. What should we do about games that are too difficult for many to play?

Let’s be clear though, this isn’t a topic exclusive to challenging action games. I personally stopped playing Ibb and Obb (Codeglue/Sparpweed 2013), an incredibly well-made puzzle game, in no small part because there were some secret bonus puzzles that were so incredibly frustrating to figure out that it drove me up a wall. Logic puzzles, mysteries, and strategy conundrums can be just as frustratingly challenging for different kinds of players as anything found in an action game.

Part III: Why Have Variable Difficulty?

Having Variable difficulties, however, is an issue that has a tendency to open up its own can of worms. Having modifiers like an Easy Mode can be humiliating in its own way, especially when the game goes out of its way to add a bit of flavor text to it with belittling descriptions like, “this is the best mode for noobs,” “casuals,” “weaklings,” or other similar language.

As a side note, you might be thinking to yourself that those are “objective terms describing the player’s skill level,” and even if they are, which they aren’t really, it is still a demeaning way to be talked to especially by a piece of entertainment and art (especially one that you paid for to have fun). For a lot of people, playing on the easiest difficulty can be just as embarrassing for them as playing on the hardest difficulty can be a badge of honor for others. Many people, myself included, will insist on playing games on the hardest difficulty available. Personally I do it because I find most of a game’s issues get magnified on harder difficulties, I tend to enjoy the extra challenge, plus I also like the small ego boost that comes with it.

But some of the most interesting variable difficulty comes not from selectable difficulty, but under-the-hood difficulty. A small study was actually conducted by Robin Hunicke of Northwestern University about The Case for Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment in Games. The experiment uses an algorithm to, among other things, change the difficulty of a first-person shooter game. This is done via changes on the “Supply” side which is defined as health packs, ammunition, and weapons. Other interventions can include modifying the player’s hit points, the strength of their attacks and weapons, their accuracy, and properties of items in the playfield or player inventory. As well as on the “Demand” side, which is defined as interventions that can manipulate the impact of enemies by changing their class, number, hit points, weapon, or location (before spawn). They may also adjust enemy attack strength, accuracy or AI states and so on (Hunicke, 2004).

The experiment wasn’t necessarily trying to ruin the game through variable difficulty. Instead it was trying to ensure an equal level of challenge and discomfort, while still maintaining a feeling of safety for players at all skill ranges. In more ways than one, the experiment worked quite well.

“There was little correlation between a player’s self-rating (with respect to games in general or Case Closed in particular) and their actual performance. In both adjusted and unadjusted games, several players who rated themselves relatively high (3-5) performed on par with others who had rated themselves as novices (1-2), and vice-versa.

Regardless of aptitude or exposure, it seems, people are likely to assume that they have failed to meet the standard for expert (5) or even good (3) performance. In the post-test debriefing, several subjects bemoaned their poor performance, despite ranking in the top third.

Subjects’ perceptions of difficulty did not correlate with their self-rating, either. Experts familiar with Half-Life and novices who rarely play shooters both rated the game as somewhat to extremely difficult (3-5). As of yet, there is no significant correlation between adjustment and difficulty evaluation (Hunicke, 2004).”

Now, keep in mind, that means that both expert and novice players rated the game as very difficult after their difficulties were adjusted. Unfortunately, the experiment did not ask a question I believe is central to the topic of variable difficulty (and this application of it in particular). I wish the experiment also recorded responses and feedback after each player was told that the game’s difficulty was altered on the fly. Having a game ask you mid-fight if you want to lower the difficulty can feel insulting for some, if not most players. In the event where a game takes the liberty of changing the difficulty without telling you, this can sting pretty badly. Especially if scores, achievements, or any kind of recorded or personal metric is involved.

As such this can be a dangerous method with regards to player enjoyment. It might be fine until players start talking with each other and learning about what the algorithm looks for. Even if it doesn’t necessarily come down to players gaming the system in order to perhaps overcome a boss that they might be struggling with by simply throwing themselves at it endlessly, it still has a huge impact on the experience. So now, we get to the meat of it.

Part IV: Is Difficulty Prohibitive?

It definitely can be. I know no shortage of people who chose to not purchase Cuphead or Sekiro primarily because they cited how difficult it would be, despite thinking it looked like something they might enjoy. They believe – rightly or wrongly – that they would not be able to complete the game or enjoy the process of playing it due to the difficulty of the experience.

It is seldom that games, through word of mouth and press coverage alone, have an air of challenge around them so strong that it can disincentivize people wanting to play them at all. This is generally why games will often use escalating challenges – building a player up from a basic principle to master different mechanics slowly over time. This is a logical progression of the Teach/Test/Trial trichotomy that I believe is present in most if not all games. Even Cuphead and Sekiro have such learning curves in their systems but in those cases, it can be the overall flow, pacing, and precision necessary that makes the games so hard to beat at a base level.

There’s a saying in game design that every game is “built to be beaten,” but that can have some nuanced meanings and implications.

Games with variable difficulties are built to have layers of ‘beat-ability’, to the point of being vastly different types of games. Borderlands 2 is an entirely different game from a New Game to Ultimate Vault Hunter Mode. It requires different tactics, different skill sets, and ultimately more game knowledge. Conversely Darksiders III (Gunfire Games/THQ Nordic, 2018) on Easy mode is relatively straightforward and a consistently streamlined experience – even some puzzles become more accessible by virtue of being less harmful to the player if they are failed.

By nature, games with fewer difficulty options are going to have fewer layers of ‘beat-ability’ and as such, fewer people will be able to beat them. When difficulty is there to impose a challenge on the player, it is possible that some players will not be able to beat the challenge. This fundamentally means that difficulty in games acts as a prohibitive barrier on further content in a game. You (often) cannot see the rest of what a game has to offer in its content if a given challenge is too difficult to overcome.

Consider though that all games face this issue with some audience. Even games as mechanically simple as Undertale (Toby Fox, 2015) or with no enemies at all can still be difficult to play for certain audiences. Players who are blind, deaf, have motor function impairments, or any variety physical, cognitive, or sensory impairments also face steep barriers to entry for most if not all games.

For them and so many others, they might often get the half-baked concession of, “you can just watch someone else play it.” Which can feel even worse to hear than it feels to say to some individuals. Experiencing art vicariously is always a hinderance on true appreciation and understanding, doubly so when the main draw of the medium is its interactivity. (As an aside: Streaming and sharing videos of games that the viewers can’t or otherwise wouldn’t play is one of those deep, deep rabbit holes I mentioned at the top of this piece. It is also, unfortunately, not quite within the scope of this essay.)

All this to say that by being a challenge, built to be overcome or otherwise, games are necessarily prohibitive to particular audiences. But so is a lot of art. A person with a vision impairment cannot see a painting the same way a person with perfect vision might. Nor a person with hearing impairments with music, or someone with motor function limitations play a game. Now we arrive at the central question.

Part V: Is Artistic Prohibition… Okay?

A question like this, particularly with something as subjective as difficulty, is by virtue of the topic going to have a subjective answer. But here I want to not only offer up my personal thoughts on the subject, but also share some context and explanations for my personal conclusion that has been built up over this essay. So… is Artistic Prohibition okay? Yes. Now it’s time to elaborate… and what better way than through an analogy - and we’ll use Sekiro as the game side of the analogy:

Sekiro is comparable to a fictional book written in traditional Japanese kanji.

Someone who has played other From Software games but is new to Sekiro may be akin to someone familiar with the author’s work, but needs to learn a new writing style or genre or writing structure.

Someone who is new to From Soft’s games but familiar with similar styles of game may be akin to someone who does not perfectly read traditional Japanese but is able to learn by the context of the story.

Someone who does not think they would be able to beat or even play the game is similar to someone who would have to learn Japanese in order to even brush up with the story in a meaningful way.

The average reader/player may be able to gain a cursory understanding of the text without putting in the time necessary to really dig in and understand it – resulting in a passing knowledge of the content. Opposingly, someone who has read the story several times may be able to recite certain passages, like a repeat player may recount battles and scenes in Sekiro with clarity.

The writer may have an agreement with the publisher to, in order to make the book more accessible, release the text in multiple languages – a stand in for multiple difficulty modes. Just the same though, the author may make a conscious decision to have the text remain its original language. Or in this analogy, one set difficulty.

Fans of the text or players in the community might make translations into other languages, or difficulty mods to allow a wider audience to participate. However, it is likely and almost guaranteed that some original essence of the game will be lost in translation. This is an inherent consequence of changing any original text. But it is ultimately okay, and a worthwhile benefit for its cost.

Those who make the mods and those who use them may believe it is better to get 90% of the feeling of the original game from changing it rather than the 50% or no % from not playing it.

Once the original text has left the author’s hands, it becomes art that can be interpreted and manipulated by its audience. That is simply a virtue of art and especially of mass media. With that manipulation comes alterations, sometimes in form of edits to the work. There is nothing wrong with an individual piece being changed by someone who may want to change it for themselves, such as a book’s owner making notes within the margins. Just as there is nothing wrong with the original author leaving less space than usual within those margins.

The work is theirs to fundamentally and creatively control – until the moment it is no longer in their hands. Then it becomes a joint venture between them, the player, and the rest of the community within and around the game. Now obviously this analogy isn’t perfect, and this is primarily a way that I personally find difficult games justifiable.

Now with all that said, if you are making a game and the goal is to be more accessible, it will ultimately benefit the game and its audience to have multiple difficulty modes. While not necessarily addressing the same realm of accessibility features from other mediums (closed captions, subtitles, audio descriptions, etc), difficulty can still bridge gameplay gaps for players with a wide variety of non-sensory disabilities or impairments. Anything from permanent bodily injury or chronic conditions to cognitive, motor function, or learning disabilities – and far more in between that aren’t listed here. Features to accommodate these player groups are important to consider, but I am not here to assert that they need to be in every game. Some games will be more accessible, others will be driven by their provided challenge. As Dr. Kristina Bell, a Game Design instructor at High Point University says,

“I don't believe that every game needs an easy mode. I would encourage game designers to consider including easy modes to make the game more accessible to less experienced players and people with varying degrees of abilities because more audience is a good thing. That being said, certainly there are games that are replayable and enjoyed by a diverse audience while being insanely difficult (Flappy Bird, for example). The reasons why people play games are complex. Not all games need to be "won" or "completed" to be enjoyed. I don't feel comfortable assigning limits to any games. I grew up playing games that are very hard (if not impossible) to win, and I enjoyed them immensely. I think we need a variety of games that fulfills different player needs.”

Part VI: Does it have a Place?

I spoke briefly with Dr. Bell and Dr. Kelly Tran about some of their thoughts on this topic. Both are women who have spent countless hours investigating, researching, and critically analyzing the medium of games over the past years and are now instructors of various undergraduate level videogames and media courses. Our conversation gravitated towards talk about the place of difficulty and difficult games. Particularly how these games fit in with regards to their popularity, frequency, and commercial feasibility – or potential lack thereof. Ultimately, both doctors endorsed the positives of having a variety of games and elaborated on the merits.

Like with so many other forms of art, homogeneity isn’t quite a virtue. Either in terms of creators or the experiences (games) themselves. With Dr. Bell saying, “Different games serve different purposes. We need really amazing interactive narratives that everyone can enjoy, we need mindless games for some to use to unwind, we need multi-player games to encourage group communication and social engagement, and we need really challenging games to test our skills.” This also extends to the countless genres not mentioned like puzzle games, strategy games, rogue-likes and countless more.

Dr. Tran adding, “I would argue that we should consider the quality rather than quantity of the experience. Especially with the variety of games available, we can have experiences that appeal to different kinds of players.”

While not every game needs to be a perfectly accessible experience that any passing player could pick up and enjoy, neither should every game be as aggressively challenging as Sekiro. The ideal, and in this case the reality, lies somewhere in the more complicated middle ground between the two extremes.

Even when a difficult game cannot be beaten, there is still merit. In some ways, the journey can be more important than the destination. As games are inherently interactive, the player’s own experience with the game can craft its own meta-narrative. Two people beating Sekiro have very different stories to tell if one player breezed through it while the other repeatedly struggled and overcame each challenge as it presented itself. A third player may have decided to spend their time in Sekiro endlessly sparring with a fellow immortal stranger, ignoring the larger story and world of the game. The designers of a game can craft and direct a singular, precise way to play – but every player will still bring their own context to the table and leave with a different story.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

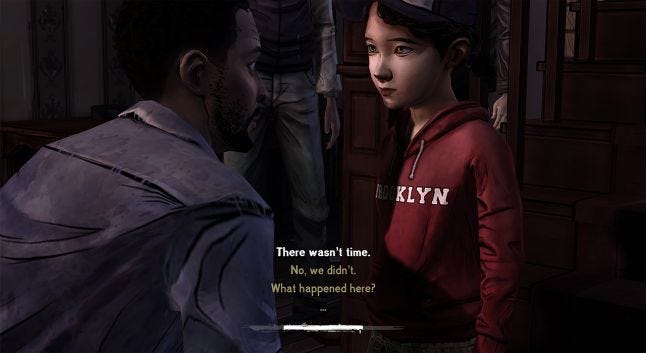

It can at times be a tough pill to swallow, especially when games we want to enjoy or want to become invested in try to mechanically strongarm us in a certain direction – desired or otherwise. “[Games] may encourage the player to behave in a certain way, such as love and protect Clementine in the Walking Dead (Telltale Games/Telltale Games, 2012). But other forces, such as a player’s beliefs, culture, background, prior experiences with games, physical world needs, shape their interpretation, enjoyment, or behavior.” (– Dr. Bell)

Mods* can and have also been used within some communities in order to make games more accessible or change them entirely. An example of the latter, Skyrim (Bethesda Game Studios, Bethesda Softworks, 2011) has had countless mods over the years adding, changing, and retconning all manner of the base game. For the former, controller functionality mods for the original Dark Souls make the game far easier to play rather than using a mouse and keyboard. There are also mods for Sekiro that can universally slow down the speed of enemies in combat, making boss encounters more digestible and overwhelming enemy encounters more manageable.

(*To be clear, mod in this context is being used to mean community created content particularly in single player games – not modified gamepads or game files used to give uneven and unintended advantages in multiplayer games. Those would be more akin to exploits or hacks.)

I know there are some within the Sekiro community that would consider such mods as ‘cheating,’ a classification I find rather difficult to endorse. Firstly, it is a single player game where progress for one player makes no impact on any other player. Secondly using any mod, even one that makes the game harder, disables achievements on platforms like Steam, which would be the main tangible way of showcasing progress or prestige within the game and community. Thirdly, people shouldn’t be discouraged from playing games they enjoy or in ways that give them the most out of the experience – within reason (another rabbit hole).

Mods hold an important place in the game industry and communities big and small despite how individuals or even developers may feel about them. “People ‘enjoy’ modding games, but they are not always engaging with it in a way that the designers may have predicted or encouraged,” says Bell. With Tran adding, “deliberately subverting the expectations of a game, through modding or otherwise, is one of the most interesting and even empowering things that players do.” Mods, to refer back on the literature analogy from earlier, can essentially act as fanfiction of the medium of video games.

Community-created mods ultimately both open up the game experience to more players, as well as open up the game experience itself. Skyrim with mods may be more approachable as the player can have more options to solve a problem, but there are also mods that add in more problems to be had. (In this usage, ‘problem’ means gameplay challenge.) But few people would consider these mods as outright cheating. Cheating as a concept, according to Tran, “can have widely varying definitions… depending on the values of both an individual and of the community around a game.” At best, it needlessly divides communities over misunderstandings and can create subgroups. At worst, it can cause vitriol and toxic behavior to spread throughout and beyond a community and make an entire game harder for new players to approach.

Skyrim has now come out almost 8 years ago, and perhaps was never really considered a gameplay-challenge focused game like Sekiro. Despite their multitudinous differences, there are key similarities between the two. Both are strictly single player, and both can provide wonderful experiences to their players. Both have mods that impact gameplay, and both have passionate communities that have followed the game since their release. But I sincerely hope that it doesn’t take 8 years for everyone to be more okay with mods allowing others to more easily play games like Sekiro. The game deserves better and we as a video game community and industry can do better.

Part VII: My Conclusion

At the beginning of this piece I asked the relatively benign question of who should be able to experience art? A question that, undoubtedly, has been made far more complicated by these past 5000 or so words without ever getting much closer to a concrete answer.

But the main contention of that question lies in its nuance. Not everyone is going to be able to experience all art – not only by virtue of volume (there are enough movies, books, songs, etc. that no one could take in all of even a single medium in a human lifetime), but by virtue of access. In this particular case: access via difficulty. This piece has covered what difficulty can mean for a game and how that can translate into the player experience across different games, styles, and contexts. While it is important to understand where difficulty can come from and the purposes it can serve to improve an experience, it is important to understand that it creates variety within the medium. Variety that, even if it means not every player can enjoy every game, is ultimately beneficial for the impact video games can have as a form of art.

I have an admittedly broad personal definition of what can be categorized as art, but games as an art form exist in a strange limbo between puzzle, movie, book, and visual piece. Some may argue that the moment you press compile, or export, or save a final version that a game is a complete work of art; that a painting is art up to and including the last brush stroke touching and leaving the canvas. Or a book is art in any state even long before the last word is written in.

I would disagree.

Art, to me, necessitates an audience. The book is inert and merely ink on paper until someone comes along to open it, read it, and consume its language to the best of their ability. The painting is various chemicals and oils on a sheet until someone takes it in with their eyes and mind, and they interpret what their brain lets them see. A game is nothing but slumbering code until a player presses the start button to bring it to life. Whatever experience may come after is entirely unique to them, and forever exists as part of their unique version of the art.

For better or worse, that game may resist. It may literally fight the player every step of the way from start to finish. Like a book with every page stuck together, hiding a world within to spite the reader as they gently but determinedly pry the pages apart. Ultimately, that difficulty in making it through the game is an important portion experience of the game itself. Games like Sekiro tell a story through their mechanics – a struggle against far greater, deadly, and sometimes seemingly supernatural forces as someone learns to adapt to new situations with new tools and blossoming abilities. In so many ways, the player mirrors the main character, struggling through their own journey both within and without. That’s an experience worth persevering through. Even if it means others cannot do the same.

/St. Germain

Carpenter, A., 2003. Applying Risk Analysis to PlayBalance RPGs. Gamasutra.com.

Crawford, C. 1984. The Art of Computer Game Design. Berkely, California: Osborne/McGraw-Hill.

Green, C.s., and D. Bavelier. “Action-Video-Game Experience Alters the Spatial Resolution of Vision.”

Psychological Science, vol. 18, no. 1, 5 July 2010, pp. 88–94., doi:10.1111/j.1467-

9280.2007.01853.x.

Hunicke, Robin, and Vernall Chapman. “AI for Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment in Games.”

Https://Www.aaai.org, Northwestern University , 2004,

www.aaai.org/Papers/Workshops/2004/WS-04-04/WS04-04-019.pdf.

Juul, Jesper. “Fear of Failing? The Many Meanings of Difficulty in Video Games.” Www.jesperjuul.net,

Simon Fraser University, 2009, www.sfu.ca/cmns/courses/2011/260/1-

Readings/Juul%20%20Fear%20of%20Failing%20Video%20Games.pdf.

Steiner, George. “On Difficulty.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 36, no. 3, 1978, pp.

263–276. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/430437.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like